Director: Franklin J. Schaffner

Producer: Frank McCarthy (20th Century Fox)

Writers: Ladislas Farago (novel), Omar N. Bradley (novel), Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North (screenplay)

Photography: Fred J. Koenekamp

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Cast: George C. Scott, Karl Malden, Stephen Young, Michael Strong, Carey Loftin, Albert Dumortier, Morgan Paull, Karl Michael Vogler, Michael Bates, Bill Hickman, Pat Zurica, James Edwards, Lawrence Dobkin, David Bauer, Ed Binns, Paul Stevens, Gerald Flood, Siegfried Rauch, Richard Munch, John Barrie

![]()

“Where you going, General?”

“Berlin! I’m gonna personally shoot that paper-hangin’ son of a bitch!”

Many biopics are good (i.e. Ray; Walk the Line), but few become great (i.e. Lawrence of Arabia; Schindler’s List). The real-life human story is almost always spectacular — why else would Hollywood turn it into a movie? — but something usually lacks, either in a script that can’t keep up with the true story, or in a performance that can’t keep up with the real-life popular figure. In Patton, it’s safe to say that all these things are spot on, the screenplay masterfully co-written by Francis Ford Coppolla and the lead part played by a never-better George C. Scott, who in his career performance actually becomes four-star General George Patton, the “only Allied general truly feared by the Nazis” during WWII.

Producer Frank McCarthy, former Secretary of the War Department General Staff, actually knew Patton during the war, after which it took him 19 years to get the film made. He had first tried in 1951, six years after Patton’s freak car accident death in Germany, but Patton’s widow nixed the idea, carrying a grudge against the media, whom she felt was the cause of many of Patton’s career problems. Indeed, throughout the movie, newspapers are depicted as printing many controversial things Patton said “off the record.” (A) After she died, the children also blocked the project, pushing it all the way until 1970 before the picture could be made. In the end, McCarthy’s production battle brought him complete vindication, earning seven Oscars, including one for himself — Best Picture.

The film opens in Tunisia where U.S. forces have just been decimated by legendary Nazi general Erwin Rommel’s feared Afrika Korps. As a response, Gen. Patton (Scott) is brought in to lead the Seventh Army, his brashness deemed necessary to discipline the troops and boost morale. Before long, Patton has made it his personal mission to both match wits with Rommel (Karl Michael Vogler) and rival Allied commander British General Montgomery (Michael Bates) to Sicily, succeeding in both. But when his own furvor leads him to famously slap one his own soldiers, calling him a coward, Patton is reprimanded by Gen. Eisenhower, replaced by old friend Gen. Omar Bradley (Karl Malden) and sent on probation to serve as a decoy in Cairo. Convinced Patton is about to wage a major offensive, the Germany Army diverts its attention to him in Egypt, leaving the backdoor open for D-Day on the beaches of France. As the war wages on, Patton is reassigned to battle, leading the Third Army across France to play a pivotal role in the snowy Battle of the Bulge. When the war is over, he is named military commander of post-war Germany, but his boldness once again gets him in trouble, as reporters quote him comparing Republicans and Democrats to the Nazi party, in as much as being blind party followers.

Such highs and lows, pride and shame, success and failure, all seem to define Patton as a historical figure. They also make for one of cinema’s most fascinating character studies, bringing to the screen a complex character who admits he’s a primaddona but knows he’s the best damn general the Allied forces have got. He’s a man who has the audacity to desire a one-on-one duel with Rommel, the outcome determining the fate of the war, and chutzpah made him #29 on AFI’s Greatest Heroes.

“Give George a headline and he’s good for another 30 miles,” Bradley says, summing up a man who craves the glory of battle so much to a fault, a fault he himself realizes. Looking out over a field of dead soldiers, Patton says, “I love it. God help me, I do love it so. I love it more than my life.”

In fact, as a firm believer in reincarnation, his life is but a small piece of an ongoing history of which he is part. And he believes it his recurring place in history to be part of mankind’s biggest battles, having flashbacks of the Battle of Carthage and premonition of the Battle of Bulge as a reflection of his “own” experience in the wintery defeat of Napoleon. He’s described as “a 16th century man living in the 20th century … a romantic warrior caught in contemporary times.” He’s at once a warrior and a poet, a hero and a monster, and a man who when asked if he reads the Bible replies, “Every Goddamn day.” Patton does not blindly hold its human subject up on a pedastal, but rather, like Lawrence of Arabia, presents the war hero for all his strengths and all his flaws.

This duality may help to explain why both ends of the political spectrum interpret Patton in completely opposite ways, each side claiming the film for its own. Military hawks embrace the film for Patton’s take-no-crap hardness, his belief that it’s “the evident destiny of the British and Americans to rule the world” and the countless scenes of military strategists, both German and American, pointing to huge wall maps and plotting detailed offensives. Equally so, anti-war crowds embrace the film for its recognition that even the great military minds border on moral crisis — as two troops converse: “There goes Old Blood and Guts.” “Yeah, our blood, his guts.” — a theme backed by intermittent depictions of the horrors of war, like Patton standing by a row of graves and saying, “Our graves aren’t gonna disappear like everyone else who fought here. The Greeks. The Romans. Carthaginians. God how I hate the 20th century.” What an achievement to make a film so complex that it can be embraced by both sides! Remember, Patton was released in 1970, right at the height of the Vietnam War. So when the famed general stands before his troops on stage and announces, “Americans have never and will never lose a war,” it’s seen by left as a stinging irony, and by the right as a rally for the good old days.

One thing that both sides can agree upon is the performance by George C. Scott. Their verdict: flawless. An amazing feat considering the character he plays is so flawed. Aside from his uncanny physical resemblence, Scott seems to embody Patton’s entire being, earning a spot on Premiere’s 100 Greatest Performances by playing the part with a Henry Hathaway-type boldness (B) and mimicking Patton’s walk from 3,000 feet of film, including documentaries, newsreels and footage from the U.S. Signal Corps (A). Scott also claimed to have read about a dozen books in preparation for the role, and during the shoot, he further got into character by wearing authentic reproductions of Patton’s uniforms, decorations and accessories — most famously that riding crop and those ivory-handled six guns.

“I have enormous affection for Gen. Patton, a feeling of amazement and respect for him,” Scott said. “I hope the film comes out not as an apology but as a fair, respectful portrait” (A).

By Oscar season, everyone was touting Scott as the hands-down favorite, while he warned that if he won he would not accept the award, hating the idea of actors being in competition with one another. When his name was called as the winner of Best Actor anyway, the crowd roared in approval and McCarthy accepted the award on his behalf.

Also absent from the ceremony was Coppola, who along with co-screenwriter Edmund H. North, took home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. Based on Bradley’s book A Soldier’s Story and Ladislas Farago’s book Patton: Ordeal and Triumph, the screenplay for Patton remains one of the best ever written, voted #94 all-time by the Writers Guilds. The script is so clever, case in point being the ironic near-death of Patton at the end of film: “After all I’ve been through, imagine getting killed by an ox-car.” Futhermore, it seems fully intent on opening up Patton’s perceived connection to the history of the world, giving him several great monologues on the subject: “In my dream it came to me that right now the whole Nazi Reich is mine for the taking. Think about that, I was recently sent home in disgrace. Now I have precisely the right instrument at precisely the right moment of history in exactly the right place.” Such beautiful writing is largely the result of Coppola, as North was brought in later to help flesh out the dramatic aspects of the script, and boy does Coppola hit a home run. Just two years before the endlessly-quotable The Godfather (1972), Coppola fills Patton’s mouth rousing articulations, particularly in the opening monologue: “You must remember that no bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country!”

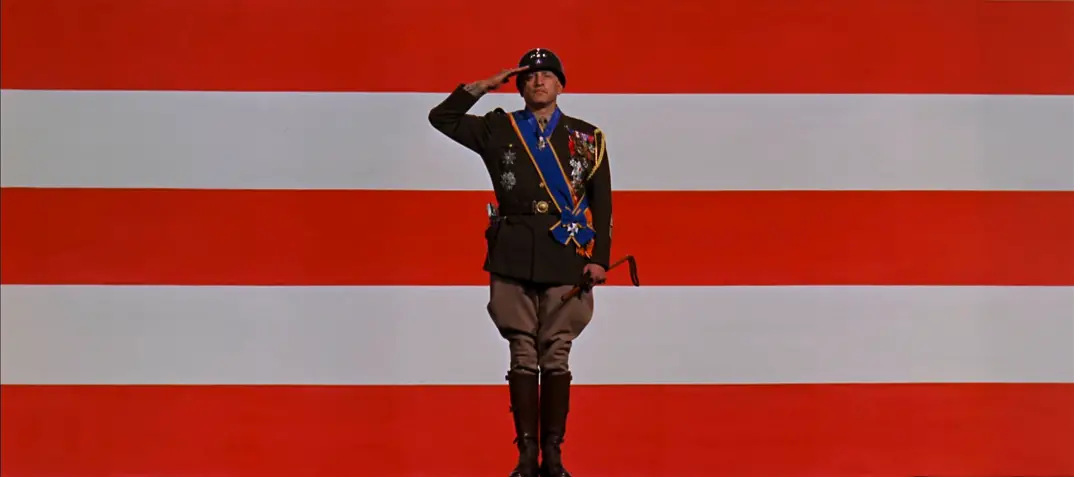

The scene, one of the most famous in movie history, is aided greatly by director Franklin J. Schaffner’s decision to shoot it against a giant American flag backdrop. Schaffner, who is certainly not remembered as a great director over his career, came through with a masterpiece in this, his follow-up to Planet of the Apes (1968). Sprinkled throughout the film are reminders of why he won the Oscar for Best Director — the red and white stripes behind Patton’s body representing the duality of his character; the beauty of military vehicles moving in silouhette against the sky, or appearing upsidedown in a reflection of water under a bridge; the subjective shots of Patton’s binocular view; an extreme close-up of an officer blowing steam into the camera lens, which stands in for a mirror; the constant use of Patton in mirrors to further hint at his duality; the use of a ceiling mirror to create an “upsidedown shot” at the exact time Patton’s world has been turned upsidedown when told he’ll be nothing more than a decoy; and a shot of Patton small in the distance of a hallway, staring out a window and screaming at his own frustration of being small in the war: “An entire world at war and I’m left out of it?!?”

Of course, the film, like its lead character, is not without its flaws, most of which are some derivative of time. Time has not been kind to the battle sequences, which look authentic enough, but can’t help but seem extra stagey compared to such modern efforts like Band of Brothers. Second, is the film’s run-time of 170 minutes makes for a long, drawn-out character study, providing ample scope for Scott’s amazing performance, but which doesn’t help casual viewers in the accessibility department. And finally, time has knocked the film off the AFI list, where it once appeared at #89 in 1997. Why is it that epic war films like Patton and All Quiet on the Western Front (1940) fell from the list? Was it the result of a nation (and liberal Hollywood) tired of war? And if so, wouldn’t the anti-war elements of such films be all the more reason to honor them? Patton himself knew about time, its cycles and its reincarnations, so maybe the film will be back.

Until then, enjoy it for what it is — the perfect Saturday afternoon TV movie, one you can pick up in the middle and always expect the pleasure of George C. Scott, completely in his element, parading to Jerry Goldsmith’s trumpeting score. But each time you watch, try not to take for granted the poignant political and ethical themes the film presents. Nothing can be more timely than a scene where a reporter asks Patton, “You do agree, don’t you general, that our national policy should be made by civilians and not by the military?” “Of course I agree. But the politicians never finish. They always stop short and leave us with another war to fight.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: CBS Fox Video, laserdisc, 1989

CITE B: Film Dictionary or 1001 book, where did i read that?