Director: Kevin Smith

Producers: Scott Mosier, Kevin Smith

Writer: Kevin Smith (screenplay)

Photography: David Klein

Music: Love Among Freaks, The Jesus Lizard, Seaweek, Bad Religion, Stabbing Westward, Alice in Chains, Girls Against Boys, Bash & Pop, Supernova, Corrosion of Conformity, Soul Asylum

Cast: Brian O’Halloran, Jeff Anderson, Marilyn Ghigliotti, Lisa Spoonhauer, Jason Mewes, Kevin Smith, Scott Mosier, Scott Schiaffo, Al Berkowitz, Walter Flanagan, Ed Hapstak, Lee Bendick, David Klein, Pattijean Csik

![]()

What do a college tuition, comic book collection, FEMA car reimbursement and countless credit cards have in common? Kevin Smith used them all to fund Clerks in 1994. (A) A 23-year-old film school drop-out at the time, Smith shot the film over three weeks in the New Jersey convience and video stores where he worked and did it for just $27,500 with mostly local friends and his own production company, View Askew. Before long, the film got the attention of now-disgraced Miramax head Harvey Weinstein, whose distribution allowed the film to gross $3 million in the U.S.

This “making of” story is one of the most famous independent success stories, so cool in fact that Empire ranked Clerks the #4 Greatest Independent Film of All Time around the turn of the century. In the film history books, it remains one of a handful of films, along with Soderberg’s sex, lies and videotape (1989), Jordan’s The Crying Game (1992) and Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992), that catapulted the independent film industry into a legitimate enterprise.

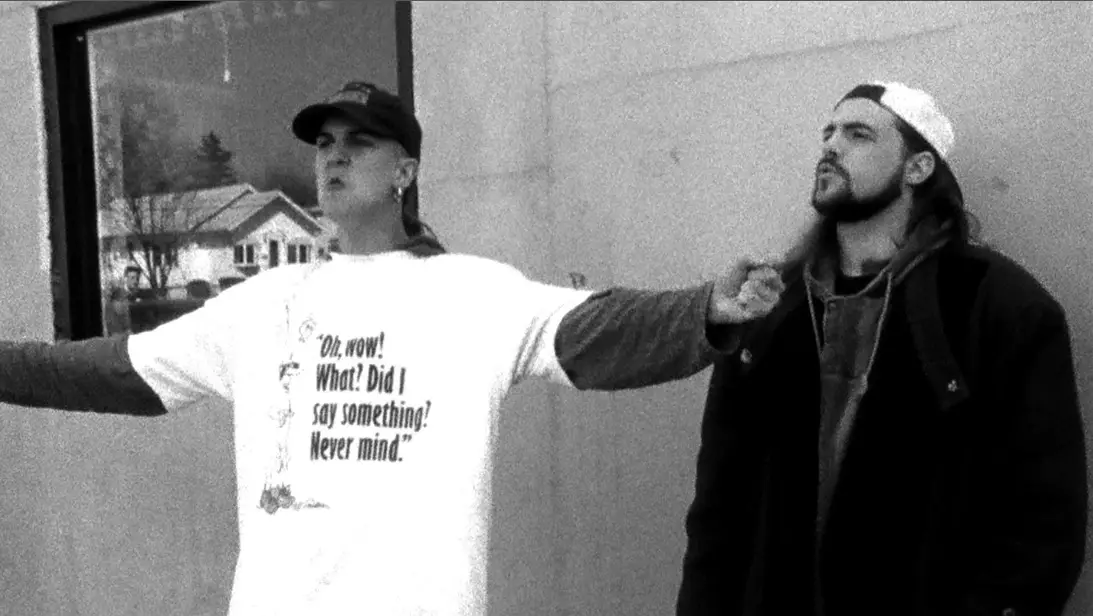

Dante Hicks (Brian O’Halloran) isn’t supposed to be at work today. He just closed down the Quick Stop convenience store the night before and he’s supposed to play hockey at 2 p.m. But a call from his boss changes all that, and there Dante sits, bored out of his mind as he interacts with an array of customers, including a pair of born loiterers, dancing junkie Jay (Jason Mewes) and his stoic “heterosexual companion” Silent Bob (played by Smith himself). Mostly, Dante passes the time by chatting with Randal Graves (Jeff Anderson), his ultimate slacker friend who works at the video store next door. Together, the two engage in pointless banter, while trying to help Dante decide if he loves his girlfriend, Veronica (Marilyn Ghigliotti), or if he should opt for his crazy ex, Caitlin (Lisa Spoonhauer). Amid the madness that ensues throughout the day, all Dante can repeatedly say is, “I’m not even supposed to be here!”

The plot, essentially a day-in-the-life of a convenience store clerk, is as simple as it gets. And if a lack of storyline is one of the film’s flaws, its bigger flaw is the less-than professional acting. Quite often the characters sound like people reciting their lines, rather than having free-flowing conversation. Still, Smith’s dialogue is so good, so funny, that viewers are willing to overlook its amature delivery. Ed Gonzalez of Apollo Guide may have described the script best: “Like a grass roots Woody Allen film, Clerks is one humdinger of a stand-up routine.”

Indeed, Clerks feels like classic stand-up comedy, with one joke after another, one bit after another, all divided into episodes and labeled by various states of mind (i.e. “Malaise,” “Whimsy,” “Catharsis”). These episodes contain some of the most outrageously funny moments in film comedy history — introducing the disgusting term “snowballing,” debating Return of the Jedi’s explosion of the Death Star as killing countless innocent contractors, and the funniest erection ever recorded.

The majority of the humor is raunchy as hell, your first clue being an animated clown who walks out in a thong during the opening credits. The film is not for everyone, certainly not for grandma, probably not for mom, but the perfect movie for the immature adolescent at heart. If there was ever genius in crudeness, it’s Clerks, a film featuring dialogue described by Empire as “balls-out.” Consider Dante’s rant: “Why do I have this life? I’m stuck in this pit, working for less than a slave wages, working on my day off, the god-damned steel shutters are closed, I deal with every backward ass f*ck on the planet, I smell like shoe polish, my ex girlfriend is catatonic after f*cking a dead guy, and my present girlfriend has sucked 36 d*cks!” Randal replies, “37.”

It’s no surprise the film was originally slapped with an NC-17 rating, but Miramax hired a lawyer and got it down to R, without having to change a single word. Still, Smith’s biggest achievement may be that somehow through the crude humor, his script offers unique insight into its chracters. Just look at how Smith converts crude dialogue into keen observation on Dante’s resistance to risk: “My mother told me once that when I was three years old, my potty lid was closed. And instead of me lifting it, I shit my pants. The point is, I’m not the type of person who will disrupt things just so I can shit comfortably.”

If the dialogue is raw, so is the film’s look — grainy, low-budget, black and white stock. Smith might like to claim the B&W as an intentional choice to resemble store surveilence cameras, but even he will tell you it’s all done because B&W is cheaper. Throughout the shoot, such choices of necessity were made, namely the idea that someone put gum in the locks, forcing the store’s steel shutters to be closed. This little detail was added because Smith was only allowed to film in the store after hours, 10:30 p.m. – 5:30 a.m., and he couldn’t have all the daytime scenes look like night. Indeed, Smith was a true moonlighter, working at the Quick Stop by day and shooting the film by night. “Some days I had to like turn around and jockey the register ten minutes after we’d done shooting.” (A)

With such a grueling schedule in the hand of a rookie filmmaker, no wonder some of the editing is sloppy. But the raw feeling adds to the product, giving an almost cinema verite style. Smith rarely attempts camera movement, with the exception of the scene in the car on the way to the funeral, a minute and a half single-take with 34 pans back and forth between Dante and Randal in driver and passenger seats. Overall, Smith opts for the action to unfold theatrically, the camera dead-on looking at the counter. “I was like, let’s keep it simple, basic, and that had a lot to do with laziness and lack of confidence,” Smith said. “Basically we are always looking in one direction.” (A)

Though Smith kept his directorial approach rather basic, he won the Filmmakers Award at the Sundance Film Festival, the highest prize awarded. And at Cannes, he won both the Award of the Youth and the Mercedes-Benz Award. At the same time, Clerks became a unanimous cult hit with lowbrow audiences. I’ve always been fascinated by the film’s ability to go either way — adored by serious filmmakers as a rebellious, low budget little film, but also by foul-mouthed teenage punks who follow Jay’s call to “drink some beers, get ripped and hopefully get laid.” What a curious duality, that Smith can win prizes at Sundance and Cannes, while at the same time appear with Mewes in the music video for Afroman’s “Because I Got High.”

Which side is the real Smith? The truth may lie in Randall’s reprimand of Dante: “You know, that guy Jay’s got it right, man. He has no dillusions about what he does. Us, we like to make ourselves seem so much more important than the people that come in here to buy a paper or, God forbid, cigarettes. We look down on them as if we’re so advanced. Well if we’re so f*ckin advanced, what are we doing working here?”

Smith is glad that Jay, though a punk, at least has no dilusions about what he is. Perhaps this is Smith himself — a punk filmmaker with no illusions about what he really is. As such, he was perhaps the best person to capture what it was like to be a youth in early ’90s America. To me, no one has captured that feeling better than Smith in the final seconds of Clerks, as Dante sings “Berserker” in an attempt to get Randal to “wrangle” out the door (a scene that became the ending when several of Smith’s mentors told him to cut his original idea: to have Dante killed).

Where did Smith’s “voice for a generation” begin? When did he himself go from Dante to director, “to go off and make something of himself,” like Veronica says? Smith fondly recalls how his epiphany came when he went to New York to see Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1991). “This guy from Austin, Texas — not from Hollywood, not from New York — had made a film that’s playing here in New York and look at all these people here to see it! And he’d made it for such a low amount of money. But by the end of the film I was thinking, I could definitely do this! And oddly enough it was the raction that Clerks would have a few years later. Film students told me, ‘Your movie made me want to be a filmmaker. I knew that if you could do it, I can do it.'” (A)

Smith would enroll in Vancouver Film School, where his documentary project imploded but he salvaged his grade by making it a doc about how his doc fell apart — The Crumbling of a Documentary. After just four months, he dropped out, allowing himself to recoup half the tuition loans and put it toward Clerks. His reason for dropping out seems much like his reason for going in the first place. “They said, ‘What we do is teach you hands-on; you get your hands on the equipment, you make films. We skip all the bullshit theory of most film schools.’ That sounded good to me.” (A) Such a statement is telling. Is film theory really “bullshit” to Kevin Smith? Perhaps this is why Smith’s understanding of mise-en-scene or sophistication of camera movement will never be on par with the greats, and why his reverence as an independent artist never quite reached the point of John Cassavetes in the ’70s or Jim Jarmusch in the ’80s.

I suppose one could argue for Smith as a poor man’s auteur — he’s at least consistent in his use of repeat characters, references to hockey and Star Wars, or use of the “sh” gimmick (“Breakfast Shmrekfast”). Still, he’ll never be considered a great filmmaker taught in the world of academia. No doubt he’s been asked to speak to aspiring filmmakers, but mainly as the independent, economical, amibitious success story he is. What irony, that this guy who called “film theory” bullshit, who was considered the joker in the back of the classroom, who dropped out of the program after four months, became the inspiration for so many of his generation to go to film school.

This may explain the lament from some critics, who for the last decade have not been kind to Smith, even as he’s tried reinventing himself. After Chasing Amy (1997), which garnered a 91% on rottentomatoes, Smith has been unable to crack 68%. When he tried doing something different in Jersey Girl (2004), the critics bashed it as a mainstream crowd-pleaser. Still, I always had a little compassion for Smith, if only for this reason — imagine you were the one trying to sell Bennifer a year after Gigli (1993). More recently, came Zack and Miri Make a Porno (2008), where Smith shrewdly combined forces with Seth Rogen, a new comedy voice for his generation. And between those films, Smith brought us Clerks II (2006), adding Rosario Dawson but not much else to the original.

You see, in a way, Clerks has never left Kevin Smith. Its characters, namely Jay and Silent Bob, have reappeared in almost all of his subsequent films, from Mallrats (1995) to Chasing Amy (1997), Dogma (1999) to Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back (2001). Meantime, Clerks keeps trying to resurface, as a live action TV pilot (1995), cartoon TV series (2000), comic book series, and finally, the movie sequel (there’s rumors of a third). For all this, and his continued obsession with the comic book world, Smith has accomplished, as Empire put it, a certain “domination of the geek world. Or, as he would call it, mastery of his own “View Askewniverse.” Has Smith ever really escaped the Clerks bubble? Better yet, does he ever really need to?

Citations:

CITE A: My First Movie, edited by Stephen Lowenstein (p. 79 for my lede)