Director: Roberto Rossellini

Producers: Giuseppe Amato, Ferrucio De Martino, Robert Rossellini

Writers: Serio Amidel, Federico Fellini

Photography: Ubaldo Arata

Music: Renzo Rossellini

Cast: Aldo Fabrizi, Anna Magnani, Marcello Pagliero, Maria Michi, Harry Feist

![]()

Introduction

How can I take a negative and turn it into a positive? That’s the question that faced Roberto Rossellini in 1945 when he set out to make the anti-Fascist, anti-Nazi, pro-resistance film Rome, Open City. At the time, the titular city was still occupied by the Germans, who would certainly not approve of such a film. Even more problematic, raw film stock was scarce, actors were hard to find, money for building sets was almost non-existent and a polished product was impossible without controlled studio lighting. (A) So, Rossellini did what any innovative filmmaker would do – he started a movement.

Italian Neorealism was founded on the ideal of urgent authenticity, taking a mobile camera out into the streets, trading phony sets for actual locations, making the most of natural lighting and casting real-life laborers instead of professional actors. The result was an entirely fresh filmmaking style that would later evolve into the Dogme 95 and cinema verite styles. Adding to the authenticity was the constant threat of German oppression. For this, the “making of” Rome, Open City became the stuff of movie legend, with Rossellini and crew hiding cameras and shooting their film undercover.

![]()

Plot Summary

Co-written by future director Federico Fellini (La Dolce Vita, 8 1/2) and favorite Rossellini collaborator Sergio Amidei (Paisan, Germany Year Zero), the film follows Communist resistance leader Giorgio (Marcello Pagliero), resistance operative Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), his pregnant fiancée Pina (Anna Magnani) and the sympathetic Catholic priest, Don Pietro (Aldo Fabrizi). Together, they trade secrets, print fake IDs and lead the underground resistance against the German occupiers.

You might say the plot is a bit like Casablanca (1942), where Giorgio is an Italian version of Victor Laszlo and Pina is Ingrid Bergman. Perhaps, then, it is no coincidence that Bergman fell for Rossellini while shooting Stromboli (1950), sparking an international love scandal that produced the talented daughter Isabella Rossellini (Blue Velvet) and a number of Rossellini-Bergman collaborations — Europe ’51 (1952), Journey to Italy (1954), Fear (1954) and Giovanna d’Arco al Rogo (1954).

While Rome‘s characters’ fates may be doomed – Pina is gunned down, Giorgio beaten to death, Don Pietro shot by a firing squad – their cause is not. In the film’s final image, a group of children tragically witness the murder of Don Pietro, then walk, arm-in-arm, across the Roman skyline. While Rome wasn’t build in a day, it also can’t be rebuilt in a day. It will take future generations, exemplified by these children, walking into the distance as the film’s ultimate victors and the future of Rome.

![]()

Directorial Vision

Such a closing image is just one of the brilliant directing touches Rossellini provides. As scholar Gerald Mast observes, Rossellini uses natural, open, realistic, crisply-lit textures when showing the common Italian citizens, and contrasts that with cramped, artificial, shadowy textures when showing the oppressive Gestapo. (A) In this way, Rossellini is telling us visually who to root for and who to despise.

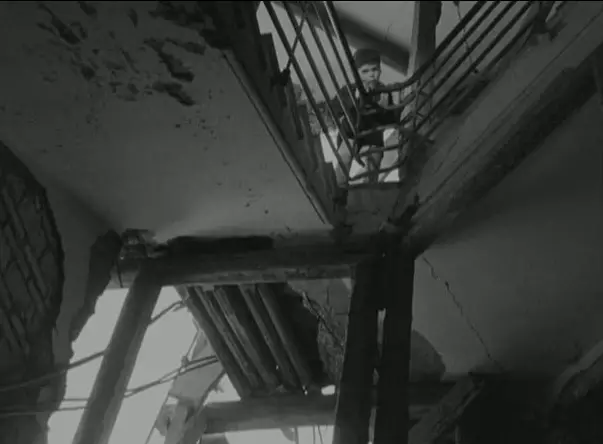

He also persuades our allegiances through the use of subjective camera. Throughout the film, we get POV shots from the point of view of the resistance fighters, watching out the window, gazing up the stairs, looking down from the rooftops.

Rarely, if at all, do we get a POV shot from the Gestapo’s point of view. Rossellini does not want us aligned with them in this intimate way. It only makes sense then that when a Nazi leans his head out into a secret passageway during a raid, Rossellini shows us, the viewers, what the Nazi cannot see — a resistance fighter deep in the frame, making his escape.

Rossellini also goes to great lengths to show us the gritty reality of the surrounding world. This was the first time audiences saw such mundane items as toilets, for example, which didn’t flush in Hollywood for 15 more years with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). This was the real world, in all its everyday glory. Gone was the artifice of the “white telephone” comedies previously produced in Rome. Here, you’ll find only black phones.

While other films had allowed viewers to escape the harsh realities of the war, Rossellini found the reality and zeroed right in on it. As Rossellini once said, “I will combine my talent with the camera to haunt and pursue the character: the pain of our times will emerge just through the inability to escape the unblinking eye of the lens.” (B)

![]()

Legacy

Watching Rossellini’s work, you can readily see the influences on Carol Reed’s stairwells and black markets in The Third Man (1949), William Wyler’s on-location streets in Roman Holiday (1953), Stanley Kubrick’s firing squad finale in Paths of Glory (1957) and Steven Spielberg’s Nazi raids in Schindler’s List (1993). Those are four directors any filmmaker would be humbled to be influenced by, let alone to influence.

The references continue in even more recent films, like the Oscar-winning Life is Beautiful (1997), where the lead actress chases after a truck in the same way Pina had moments before her death.

Even as I sit here writing this, I’m sipping coffee at Open City Diner in Washington D.C., nestled right beneath a giant mural of Marilyn Monroe on the side of a building. No doubt most residents and tourists will turn their gaze to Marilyn, but the influences of the great European filmmakers are just as prevalent. All you have to do is look around you — in the gritty textures of the streets, in the faces of common people, in the ongoing struggles of faith, oppression and race – and you’ll see that Rossellini’s masterpiece Rome, Open City is alive and well.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Gerald Mast, A Brief History of the Movies, p. 376-377

CITE B: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, p. 758)