Director: Steven Spielberg

Producers: David Brown, Richard D. Zanuck (Universal)

Writers: Peter Benchley (novel), Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb (screenplay)

Photography: Bill Butler

Music: John Williams

Cast: Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Shaw, Lorraine Gary, Murray Hamilton

![]()

Introduction

Call it the scariest horror flick ever made, a Moby Dick action adventure, a social commentary on beach towns and greedy mayors, a humanistic family story of science and wonder, one of the best film adaptations of a best-selling novel, one of the pioneering summer blockbusters, the winner of three Academy Awards (editing, sound, score) and the proud holder of the No. 56 slot on the AFI’s Top 100 Movies of All Time. Or, if you’re GQ magazine, you can take a more cynical approach and call it the beginning of the end for the Hollywood Renaissance: “It’s now a movie-history commonplace that the late-’60s-to-mid-’70s creative resurgence of American moviemaking — the Coppola-Altman-Penn-Nichols-Bogdanovich-Ashby decade — was cut short by two movies, Jaws in 1975 and Star Wars in 1977, that lit the fuse for the summer-blockbuster era.”

Still, just because many of their starry-eyed followers went on to make effects-heavy garbage for short-attention spans, doesn’t mean that Spielberg and Lucas themselves made garbage. Young Spielberg (Jaws) and Young Lucas (American Graffiti) understood film history — which is more than many of their fanboys can say — with references to John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) in both Close Encounters and Star Wars, before teaming on Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Scholar David Thomson put it best: “Like Coppola on The Godfather, Spielberg asserted his own role and deftly organized the elements of a rollercoaster entertainment without sacrificing inner meanings.” (A)

This, my friends, is the essence of The Film Spectrum, a website that urges future filmmakers to find that “sweet spot” of riveting first-time experience, yet increasing depth on repeat viewings. If you won’t take it from me, take it from Billy Wilder: “When people try to belittle The Exorcist or Jaws, I just think these people are crazy. Mr. Spielberg knows exactly what he did, and he did it brilliantly.” (B) And so, let’s all come to grips with a simple fact: Jaws is not only massive entertainment, it remains one of the best directed movies ever made. If you look at our website’s banner in this context, there are fins to the left, fins to the right, and it’s the only shark in town.

![]()

Hell on Water

“When I first hear the word ‘Jaws,’ I think of a period in my life when I was much younger than I am now,” Spielberg says in the documentary Spotlight on Location: The Making of Jaws. “Because I was younger, I was more courageous, or I was more stupid, I’m not sure which. So when I think of Jaws, I think about courage and stupidity, and I think of both of those things existing underwater.”

Spielberg was relatively unknown at the time, having directed the TV movie Duel (1971) about a killer tractor-trailer, and one big-screen feature, The Sugarland Express (1974), starring Goldie Hawn. When production on Jaws ran over schedule by four times the planned amount, the 20-something Spielberg was almost fired, but producer Richard D. Zanuck fought for him to remain on the picture. Just think of all the great movies we would have missed if Spielberg had been labeled a failure.

The reason for the delay was that the film’s star had stage fright. The mechanical shark, nicknamed “Bruce,” did not react well to the waters off Martha’s Vineyard, and it did not work most of the time. While this created headaches for production, it was a blessing in disguise, forcing Spielberg to find creative ways to depict the shark without showing it, like pulling a fishing pier, or pulling a series of harpooned yellow barrels.

![]()

Less is More

Thus, we should all eternally thank Bruce the Shark for not working. The result was a series of terrifying POV shots set to John Williams’ Oscar-winning, two-note score, which Spielberg credited for half the film’s success. The music ranked No. 6 on AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores, and can be hummed even by those who have never seen the film. Let’s face it, it’s John Williams score that got The Shark ranked No. 18 on the AFI’s Top 50 Villains

Let this be a lesson for today’s gore-obsessed filmmakers that less is more. The lack of shark appearances unknowingly thwarted the danger of the film from dating over time (if you want to date your movie, put a lot of special effects in it and wait 10 years). More importantly, the lack of shark appearances cemented the notion that the “unseen” is almost always scarier than the seen, as director Robert Wise proved in The Haunting (1963). In a modern era where audiences are now desensitized to violence, the biggest terror is that which screws with our imagination. Spielberg knew this well in the film’s shocking opening scene, voted Bravo’s No. 1 Scariest Movie Moment.

“The book does describe the shark before you see the attack. I thought what could really be scary was not seeing the shark and just seeing the water,” Spielberg says. “We’re all familiar with the water. Very few of us have been in the water with a shark, but we’ve all gone swimming. And the idea of this girl going swimming and the audience going swimming with her would have been too extraordinary if, like a Leviathan, the shark had come out of the water with its jaws agape and come down on her, and it would have been a spectacular opening for the film, but there would have been nothing primal about it. It would have just been a monster moment that we’ve all seen.”

“I really wanted to do it without seeing the shark in that case, and I wanted the violent jerking motions to just start to trigger our imaginations into either thinking about what was happening below the surface or blocking what was going on below the surface.”

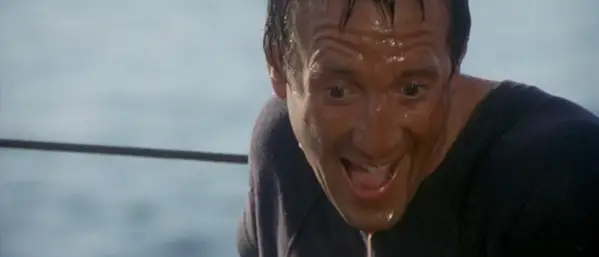

![]()

A Director is Born

Yep, that’s Spielberg himself yanking the girl underwater, tugging on a special harness for the initial shark bite. His director’s “touch” is apparent throughout the film, which remains his best directorial effort, save for his two Best Director Oscar wins for Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998).

Reflections. Note the reflection of book pages flipping in Brody’s glasses, or the reflection of the shark barrels in a window of the Orca.

Composition. Note the gorgeous composition of Quint standing on the front of the boat, one of many frames you could freeze and frame on your wall as artwork.

Slow Disclosure. Through deliberate pacing and perfectly timed reveals, Spielberg lands some of his biggest scares, be it a false alarm with a cardboard shark fin, or the very real alarm of a dead boater popping out for a jumpscare. Alfonso Cuaron used a similar approach to revealing a dead astronaut in Gravity (2013).

Familiar Image. Throughout Jaws, Spielberg makes brilliant use of familiar image, most obviously with the shark fin and yellow barrels. But it also applies to other objects, like the Kinder boy’s yellow raft.

Frames Within a Frame. Jaws features one of my all-time favorite “frames within a frame” as Spielberg shows the town of Amity through the gaping jaws of a shark.

Split Water. Admire the combination of underwater and above-water shots, using a special camera apparatus to hover on the waterline. Mike Nichols used a similar technique during the swimming pool scene of The Graduate (1967), which starred Amity’s future mayor Murray Hamilton as Mr. Robinson.

Depth of Field. Note how Spielberg uses every inch of his depth of field, that is, everything from the foreground to the background. As Chief Brody sits on the beach, various citizens approach him in the foreground, but his eyes are always watching bathers for potential danger in the background.

Wipes. Note the illusion of a continuous take as Brody sits on the beach, staring out into the water. Spielberg uses various bathers walking across the screen as “wipes” to hide each cut. Hitchcock used a similar technique in Rope (1948) to create the illusion that his entire movie was a long single take.

Zolly. Speaking of Hitchcock, Spielberg employs the so-called “Vertigo Effect” of simultaneously dollying forward while zooming backward (or vice versa). While Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) used it to show Jimmy Stewart’s acrophobia, Spielberg uses it to show Brody’s terror as he witnesses his first shark attack. The effect looks as if the image is detaching from itself.

![]()

Casting Your Actor Net

Spielberg was not only effective in cinesthetic language, he was also just as effective in getting the best work from his actors. In Jaws, he demonstrates a flexible, open-minded approach of working with his actors, particularly one moment of improvisation from Roy Scheider. After being slapped in the face by Mrs. Kinder over the death of her son, Chief Brody returns home in despair, kicking himself for not closing the beaches sooner. He sits at his dining room table and swallows back his guilt with a few glasses of wine. After sitting unresponsive to the world around him, he looks up to see his toddler son staring at him with idolizing eyes and imitating his every movement. So the two begin folding their hands and making faces at one another in a tender moment until the tension is broken by Hooper’s knock at the door. Average directors stick strictly to the script. Great directors allow themselves to capture “happy accidents” such as this, and it remains my favorite scene in the movie. Would we care if Brody lives or dies in the end without such intimate family moments?

The key to making such moments work is an ability to cast your actor’s net widely, worrying more about raw talent than global starpower. Spielberg had loved Roy Scheider as Gene Hackman’s sidekick in The French Connection (1971), so when the two met at a party, he knew he had found Amity Police Chief Brody. Scheider would end the decade with another lead role in Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979).

Similarly, Spielberg had loved Richard Dreyfus in American Graffiti (1973) and asked him to play the marine biologist Hooper. Dreyfus wasn’t thrilled about the role and came aboard kicking and screaming. But it was the best decision he ever made, as the role showed a blend of intelligence and humor that inspired his casting as the lead in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

Murray Hamilton (The Graduate) was always the first choice to play Amity’s scumbag mayor, and Spielberg cast Lorraine Gary as Brody’s wife Ellen because he liked her work on television. She was also the wife of Sid Sheinberg, president of Universal Television at the time, who had seen Spielberg’s short film Amblin and offered him a long-term contract at a low salary and the chance to direct an episode of TV’s Night Gallery.

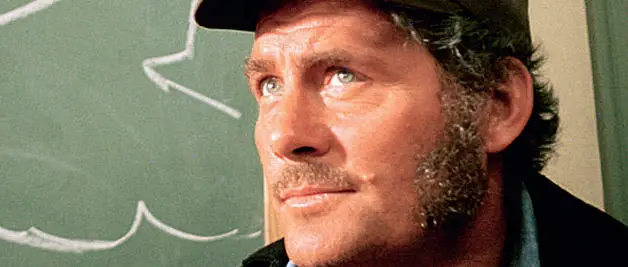

As for the role of Quint, Spielberg originally wanted Lee Marvin (Point Blank) or Sterling Hayden (The Godfather), but producers Dick Zanuck and David Brown suggested Robert Shaw, who had just wowed audiences in Best Picture winner The Sting (1973). Needless to say, he steals the show in Jaws, delivering his career performance.

Shaw’s drunken chemistry with Scheider and Dreyfus is priceless as they swap stories, compare body scars and sing “Show Me the Way to Go Home.”

![]()

From Novel to Screen

The entire notion of a man-eating shark was a simple yet novel idea for a film. Hitchcock had terrified audiences by flocks of killer birds in The Birds (1963), but why had no one tapped the dark depths and primal fears of the water? Sometimes the best ideas are right under our noses. Peter Benchley captured a universal terror in his 1974 best-seller, starting a trend of Spielberg adapting novels into hits, from Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park to Thomas Keneally’s Schindler’s List.

Benchley wrote the first draft of the script, Spielberg wrote the second, then Carl Gottlieb (The Jerk) wrote the final version. Ironically, the film’s most famous line was not even in the script. Roy Scheider improvised, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” and it became a pop culture phenomenon, voted No. 35 on the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes.

Spielberg’s favorite scene remains the U.S.S. Indianapolis speech, written three times, first by screenwriter Howard Sackler (The Great White Hope), expanded into a lengthy speech by John Milius (Apocalypse Now, Magnum Force), then rewritten by Robert Shaw for his own taste.

Quint originally was supposed to die Moby Dick-style, tangled in a harpoon and dragged underwater. Instead, Spielberg insisted on going out with a bang. After Quint loses a knife fight with the shark, Chief Brody chucks a compressed-air canister into the shark’s mouth and shoots, exploding the shark into itty-bitty fish bait. Colleagues warned that this ending might feel unrealistic, but Spielberg said that if he had the audience in his palm for two hours, he could afford to go big.

![]()

Movie Theater Memories

Spielberg’s instinct was right, as audiences flocked to the theater. Despite just a $12 million budget, the film version was given a huge marketing push, including $700,000 in TV advertising and a record 500 theaters booked for its opening weekend. (C) It wound up grossing $438 million in its first eleven weeks on the way to becoming the highest grossing film up until that point. It was dethroned two years later by Star Wars (1977), but it took Star Wars six months to reach the $100 million mark, while it took Jaws just 80 days. The financial powerhouse only grew once the film hit video, becoming the first to top $100 million in rentals. (C) Let’s face it was the perfect Friday night horror movie.

If released today, Jaws would gross more than a billion dollars in the U.S. alone. Adjusted for inflation, it remains the No. 7 highest grossing movie of all time, behind only Gone With the Wind (1939), Star Wars (1977), The Sound of Music (1964), E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982), Titanic (1997) and The Ten Commandments (1956).

The enthusiasm has not waned. I had the privilege of seeing this on the big screen recently at the AFI Silver Theatre in Silver Spring, and let me tell you, today’s youngsters still roared at the exploding finale. How jealous I am to not have been there for its initial opening. To this day, my mother fondly recalls seeing the film as a little girl, describing a businessman strolling into the theater with arrogance, then leaping over the seat into the row in front of him when the shark popped out of the water.

More recently, when I did a Jaws retrospective for WTOP Radio’s “Shark Week,” Washington D.C. residents shared similar memories:

- Diane from D.C.: “I think of seeing the movie in the theater when I was a little girl living in Fort Lauderdale (Florida), going to the beach and being afraid of going in the ocean for many years after that.”

- Chris from D.C.: “What I notice is a lot of people use the phrase, ‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat,’ which I think is from that movie. I think a lot of people here in D.C, like politicians, talk about what we’re doing isn’t big enough, we need to do something more drastic, more impressive. So I think that’s one of the things that sticks with me from the movie.”

- Veronica from D.C: “I’ll tell you what really made people go, ‘Ahhh.’ [It was] ‘doo doo doo doo.’ The music!”

- Justin from Colorado: “When we were kids, in our [public] swimming pool, they would do a ‘Jaws’ night. So, you’d go out in the pool on your tube, they’d play the movie and they’d always have some lifeguard that would wear a ‘Jaws’ outfit and scare the fifth-graders.”

- Nikel from Connecticut: “For me, it’s the Universal Studios ride. No matter how many times I did that, I always thought it was going to eat me.”

- Phil from Vienna: “I remember him throwing that canister in the shark’s mouth and then shooting it … That was a good way to end it.”

If you add up all these movie memories, you get a cultural touchstone. Decades later, we’re still living with the effects of Jaws, from Universal Studios theme park rides to Discovery Channel’s Shark Week. We’ve seen countless imitations, from three Jaws sequels (none directed by Spielberg) to copycats like Deep Blue Sea, Lake Placid, Anaconda, The Beast and Open Water. But no matter how many posers emerge, there’s no touching the original nightmare in the water, the birth of the modern summer blockbuster, the breakthrough of Spielberg’s career and the origin of a worldwide phobia summed up by the simple tagline: “Don’t go into the water.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: George Stevens Jr, Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age

CITE C: Tim Dirks, AMC Filmsite