Director: Stanley Kubrick

Producer: Stanley Kubrick (MGM, Polaris)

Writers: Arthur C. Clarke (story), Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke (screenplay)

Photography: Geoffrey Unsworth

Music: Aram Khachaturyan, Gyorgy Ligeti, Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss

Cast: Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, Douglas Rain, William Sylvester, Daniel Richter, Leonard Rossiter, Margaret Tyzack, Robert Beatty, Sean Sullivan, Frank Miller, Bill Weston, Ed Bishop, Glenn Beck, Alan Gifford, Ann Gillis

![]()

Stanley Kubrick was a wizard among men. He always sought to portray himself as larger-than-life, relocating to a secluded estate in Britain after 1961, and fancying himself as uniquely endowed, able to see life truths and spiritual connections that others could not. Maybe he could, and this would be his biggest asset. Or, maybe he couldn’t, his own pretentiousness ultimately becoming his fatal flaw. Most scholars want to believe the former, placing his crowning achievement, 2001: A Space Odyssey, as high as #15 on AFI’s Top 100 Films and #6 on BFI’s Sight & Sound Critics Poll, the mother of all “serious” lists. It’s these forces that wish to crown Kubrick as a visionary, who not only thought out of the box, but lived outside of it.

But there is a divide, even if a small one, in the scholarly community as to Kubrick’s merits. It’s unanimous that he has produced some of history’s biggest films, from The Killing (1956) to Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960) to Dr. Strangelove (1964), A Clockwork Orange (1971) to Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980) to Full Metal Jacket (1987). But some academics resent Kubrick’s self-righteous suggestion that he was himself levels above everyone else, that he could in two-plus hours explain to us not only the origins and destination of the human race, but indeed also the very meaning of life.

Scholar David Thomson trounces Kubrick as pretensious, calling him a “‘master’ who knew too much about film and too little about life — and it shows” (A). Such is cause for occasional poor reactions to his work, that he obsessed so much about vast visual compositions and grandiose spiritual themes that he often forgot about the importance of developing both his characters and the narrative. Indeed, 2001 has little narrative hook, taking an hour before we meet the protagonist (Bowman) and antagonist (HAL). But whether you laud or loathe Kubrick’s approach, there’s no denying that 2001 is his apotheosis, a film that is hands down the most ambitious and mind-blowing work ever put to film.

Based on the story by Arthur C. Clarke, the film begins with the Dawn of Man, where Darwinian man-apes discover a black, rectangular artifact, a Monolith, apparently an extraterrestrial device planted to both spawn and monitor the advancement of mankind. Immediately, the primates begin to display acts of intelligence, evolving from animals to to thinking beings, learning to use tools to hunt and war.

Suddenly, flash forward many millenia to the year 2001, where a geological team discovers another Monolith buried 40 feet below the moon’s lunar surface, a find that is all the more surprising when the object emits a radio signal toward Jupiter. Seeing as this is the first sign of intelligent life off earth, the space program sends the spaceship Discovery to follow the signal. Aboard are five astronauts, Mission Commander Dr. David Bowman (Keir Dullea), Deputy Dr. Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) and three others who are more or less being “saved for later,” their life support systems preserved in special hybernation chambers.

The mission appears to be running smoothly until the ship’s “brain and central nervous system,” a HAL 9000 series computer, referred to as “HAL,” begins to sabotage the men, worried that their “human error” will jeopardize the mission. In the end, Bowman is the only survivor and the only one left to discover a third Monolith in Jupiter’s orbit, travel through a trippy time warp and break through into a higher form of existence, reborn as a “Star Child.”

After accompanying Bowman on this entire journey, we viewers may agree with those arguments against Kubrick’s character development. The journey itself, and its giant abstract themes, are what propel the film, not its characters. At the end of the experience — and that’s what 2001 is, an experience — we hardly feel like we know the characters at all. They become instantly forgetable compared to the massive backdrop of time and space. That is true, at least, for the human characters. Everyone remembers HAL 9000 (as voiced by Douglas Rain).

Voted #13 on AFI’s 50 Greatest Villains and long considered Gene Siskel’s favorite foil, HAL has a unique ability to strike fear in viewers, a fear of the unknown, a fear of the inhuman, a fear of losing control. “Open the pod bay doors, HAL,” and responding, “I’m sorry, Dave. I can’t allow you to do that.” And like all the great villains he has a most memorable exit, being slowly unplugged, his speech pattern slowed, singing a pre-wired song, “Daiiisy. Daiiiisy.” The fact that he is just one of two non-breathing characters on the entire AFI Villains list (joining Terminator 2′s T-1000, inspired by HAL), says much about his nightmarish status. Is there anything more terrifying than this all-knowing presence, presiding over the entire ship, a piece of technology that has become too smart for its own good, speaking in monotone, computerized snippets, and watching, always watching, with that big red eye? Is there a better driving force for a film’s conflict than this, the increasing suspicion that one’s own ship is against him?

Technological takeover may be 2001‘s most poignant theme, as in today’s post-2001 era we are already seeing mankind’s increased reliance on technology. Be it the Y2K scare or the vitality of the internet, computers, iPods and GPS systems, we now more than ever require technology for our everyday survival. In 2001, Kubrick shows the whole scope of technology, from its birth, as tools for primates, to its takeover, with HAL designed to be a “conscious entity” with “genuine emotions.” The bredth of this theme, spanning billions of years, is just one part of Kubrick’s uber-ambitious thematic experiment, one that tries (and succeeds) in explaining more about human existence than any other film in history.

Kubrick runs with the idea of evolution, and views our story as if watching from a distance, waiting for us to make the next big landmark discovery that we were intended to make. It’s no coincidence that we humans are shown gathering around the Monolith exactly as the apes had, billions of years ago. Both discoveries are necessary steps toward the same end — mankind’s eventual realization of another plane of existence. Of course, this all is extremely hard for many viewers to access, and the film’s conclusion is practically incomprehensible. It is an exercise in experimental filmmaking, exposures, psychadellics and the trippy experience of seeing one’s self aging in front of him, in a well-decorated room that serves as a transitional space between the human experience and a new form of consciousness. Then again, we shouldn’t understand another form of consciousness, should we? The fact that Kubrick had the cahones and the imagination to tackle it is enough.

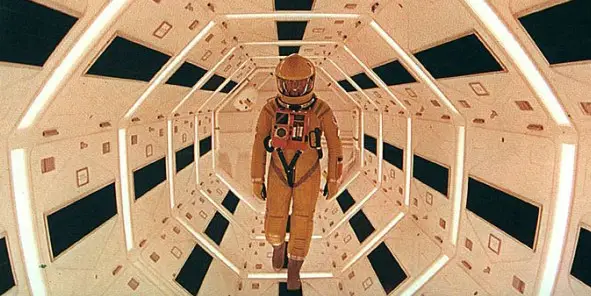

His direction is the stuff that dreams are made of — the opening shot of the camera rising up from behind the moon to see the earth and sun directly in line; the beautiful shots of prehistoric earth, appearing almost as if out of National Geographic; the low-angle shot from the base of the Monolith, looking up to see the sun peering over its brim and the moon alligned directly above; the intercutting of the ape-man crushing an animal skeleton with brief shots of a falling animal; the jumpcut from an ape throwing an animal bone high into the sky, it twirling in the air and suddenly becoming a spaceship about the same size on screen (the jump cut that spans the most time in history); the complete loss of a sense of direction, like a 360-degree tracking shot of a man running in a circular space vessel interior, or the camera appearing to look down at an astronaut from above, only to pull back and reveal another astronaut standing perpendicular to him; the subjective shots of HAL’s point of view, looking out in convex lens, the first sign of danger being that this machine would be given a “point of view;” the quick zoom cuts in on HAL moments before he strikes; and the time warp, two planes of neon colors flying toward the camera, intercut with quick, frozen images of Bowman, lights reflecting off his helmet, and extended close-ups of his eyeball, baked in over-exposed colors.

We are so in awe of what we see that we almost forget there is very little dialogue at all in the film, in fact, zero dialogue (other than ape screams) until 25 minutes into the movie. Paul Hirsch, film editor of Star Wars, told Slate.com that 2001 struck him “as a departure from all the films made before it,” remaining today a stunning blend of art and science. Take, for instance, the man-apes. Kubrick cast professional mimes wearing state-of-the-art prosthetics to create the most realistic human portrayal of primates in the history of movies, matched only by John Chambers’ work in Franklin J. Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes, released that same year. But where 2001 really takes off visually is when the story reaches outer space. Kubrick won the only Oscar of his entire career for these special effects, ingeniously designed under the supervision of tech master Douglas Trumbull, who would later join Spielberg on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Combining miniature models work way ahead of its time, and the assistance of NASA allowing them to shoot inside their anti-gravity training chambers, the film achieves a level of visual splendor and believability that has never been matched.

While other sci-fi films show their years (Lucas had to redo the effects for Star Wars; Avatar will only look faker as 3-D technology progresses), 2001 looks just as good as it did in 1968. In fact, the only thing outdated is the idea that humanity would have advanced that far by 2001, that Kubrick gave us a little too much credit, and so, only fitting that he himself never made it 2001, dying in 1999. But Kubrick’s “too much credit” is entirely forgivable, considering the film was made 40 years ago. Remember it was 1968! A whole year before the “giant leap for mankind.” If you think it’s mind-blowing now, imagine it back then, telling of Monoliths and time warps before man even made his first step on the moon.

As much as it is an awe-inspiring experience on the eyes, it is equally as flattering on the ears. Kubrick demonstrates the perfect balance between no sound at all — realizing the effectiveness of silence, that horrifying silence of space — and the most epic musical compositions in classical history. Thanks to 2001, Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra” became a Top 40 hit (B), a piece used so perfectly by Kubrick as the ape-man first wields his bone-tool, each stroke of the club moving in unison with the music, like a prehistoric xyllaphone. On top of this, Kubrick makes pop culture myth from Johann Strauss’s “Blue Danube Waltz,” setting the music to spacecrafts flowing smoothly through space or pens floating poetically inside the zero-gravity space chambers. This image, accompanied by the music, has been repeated so many times in advertising, on TV and in other films that we take it for granted that Kubrick first pieced the two together.

It’s easy to take for granted just how engrained 2001 is in our culture. HAL 9000 reincarnations have appeared in everything from The Simpsons to South Park to Family Guy, not to mention a subtle homage in Pixar’s Wall-E (2008). In Saturday Night Fever (1977), Travolta’s famous disco takes its name from 2001, and in Apollo 13 (1995), Tom Hanks tries to play the theme while in space but is overrun by Bill Paxton’s last-minute substituion of Norman Greenbaum. And, to beat all, is it any wonder that Apple, in trying to capture the idea of intellectual breakthrough, would design their iPod in the shape of the Monolith? The film is a pop culture power, making “Open the pod bay doors, HAL” the best line to quote whenever technology doesn’t want to cooperate (yell it at your computer next time it freezes).

The listology world has mirrored this cultural fascination with the film. Between the AFI’s original and 10th Anniversary Top 100 lists, 2001 jumped from #22 to #15. And in 2008, the film was named #1 on AFI’s 10 Greatest Science-Fiction Films, a slot it will likely hold forever. Trust me. If Star Wars couldn’t do it, nothing can. But there is an irony there. Star Wars comes in higher on AFI’s Top 100 Films (#13), but when talking strictly science fiction, 2001 wins. Perhaps this is because Star Wars’ appeal goes beyond its genre, into the space western, the epic adventure, the fantasy and the journey of the mythical hero, while 2001: A Space Odyssey defines everything science fiction is about — the relationship between humanity and technology, the journey into new realms, the seeking of a higher consciousness of understanding, and the intriguing promise of the infinite unknown perhaps bringing us one step closer to understanding the meaning to our being here. This is the sci-fi film by which all others are judged, a true wonder to behold, and if nothing else, a reminder of how far we’ve come and how far we’ve got to go.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: Leonard Maltin’s Top 100 Movies list