When film historian David Thomson published the 2003 edition of his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, he lamented his distaste in the direction of the film industry and ultimately decided: “Maybe this kind of book needs young authors to take up the challenge. … The desperate but idealistic attempt was and is open to everyone else to do his or her own book.”

This was the spark that ignited a hungry kid to devote years to detailed film analysis and copious note-taking, a compulsion that eventually became The Film Spectrum. Thomson’s lament spoke to more than just a cyclical changing of the guard. It captured a common feeling at the start of the 21st century that cinema as art might be headed for extinction. But the optimist in me actually hopes that today’s explosion in digital film access and instant web response will actually get more people to discover the art of the movies. What better time to educate yourself than this era of director audio commentaries, screen-grab analysis and perpetual best lists?

I suspect I am not alone in a whole generation of Millenials whose love for movies was sparked by this surge of turn-of-the-century listology, and it’s led me to ponder the very nature of such rankings. Why do critics insist upon best lists? Four-star ratings? Two thumbs way up? In many ways it’s impossible to name “bests” when choosing across genres, continents, languages and time. So why are we so compelled to play this indulgent game of apples and oranges?

I keep coming back to a simple reason — this is the fun part. It’s an ongoing game played by the children in us all, from critics publishing their latest countdown magazine, to mainstreamers debating the “five movies we’d take on a desert island.” It’s how we digest and make sense of the “movie world” around us. So while such ratings will always be debated, they are essential in peaking the interest of novices and re-engaging the minds of experts.

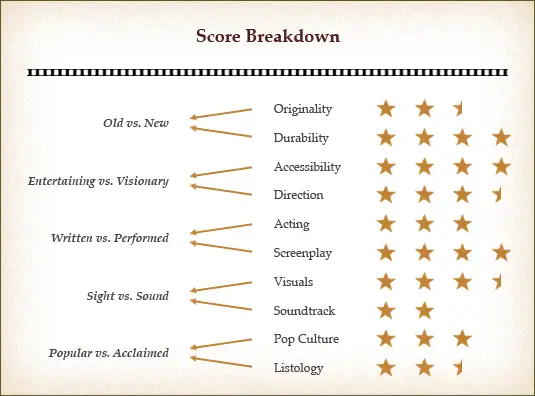

Thus, we should all have our own internal ranking systems. Mine just so happens to have evolved publicly into The Film Spectrum Rating System. It does not follow specific technical crafts, but rather broader umbrella categories that I believe drive our movie opinions — for better and for worse. Here we take the concept of the 4-star critic’s review and apply it across ten categories, each intentionally contradictory in a series of checks and balances. These “yins and yangs” make it near impossible for a film to get top marks across the board, but are purposely designed to prevent our sway to either extreme. They are meant to focus our discussion into consistent areas, the spectrum “prisms” through which we will gauge each film.

Originality

Martin Scorsese once said, “Motion pictures are part of a continuum. A living, ongoing history.” Perhaps I’m an old soul, or just naturally bend toward nostalgia, but I believe that in every endeavor of life, the most important thing is to know your history, to study the historical arc of your craft. The word “continuum” is itself a synonym for “spectrum.”

By assessing the greats of the past, we are able to gauge the suspected greats of the present and plow a path for the greats of the future. As the saying goes, if you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it. However, if you do know your history, you’ll be equipped to intentionally repeat it when necessary, emulating and synthesizing the genius minds that have come before, while knowing the latitude you have to chart new territory.

After a while, you’ll see how today’s movies might have fit into our past. A great starting point is Chuck Workman’s “100 Years at the Movies” for Turner Classic Movies. Of course, it’s limited by the fact that it was made for the Academy in 1993 and only covers Hollywood pictures, but it’s a great introduction. It should be the goal of each aspiring film buff to watch a montage like this and one day recognize all the clips. As you gradually see more of the films, you will not only increasingly enjoy these montages, you will also increasingly smile each time someone makes a film reference in your everyday life. Knowing your history can be a powerful cultural weapon.

Which brings us to the “Originality” category. This is the category that asks: has anything like this been done before? If so, is it done in a new and refreshing way? Does it take chances? Does it risk the unknown? This is where remakes and spin-offs meet their maker — that is, their original filmmaker whose spark of imagination gave birth to the idea in the first place, providing the very coattails for others to ride.

Here we reward the greatest stories never told, from new voices (Do the Right Thing, Philadelphia); new vantage points (Rear Window, Taxi Driver); new climates (Fargo), and new social perspectives (To Kill a Mockingbird, The Graduate).

Here we also reward new cinematic movements (Nosferatu, Rome Open City, Breathless); new takes on old genres (Alien, Unforgiven); new experimental techniques (Un Chien Adalou, Eraserhead); new narrative structures (Citizen Kane, Pulp Fiction, Memento); new technological milestones (King Kong, Who Framed Roger Rabbit); and historical firsts (The Birth of a Nation, The Jazz Singer).

Originality can come in the form of presentation. Here we reward all things “off the beaten path,” ballsy, bold, fresh and maverick. These films take us out of our visual comfort zones by presenting the images in a way we are not accustomed to. They make us question old modes of movie watching and shape new ways of seeing. For examples, check out Rolling Stone’s 100 Maverick Movies or Premeire‘s 100 Most Daring Movies.

It can also come in the form of story. Originals like Scarface: The Shame of a Nation (1932), The Seven Samurai (1954), Yojimbo (1961), Infernal Affairs (2002) and Let the Right One In (2008) will benefit here, while their remakes Scarface (1982), The Magnificent Seven (1960), A Fistful of Dollars (1964), The Departed (2006) and Let Me In (2010) will suffer.

It doesn’t have to be a straight remake either. Films can lose points here for simply repeating elements from previous films, like The Boondock Saints (1999) rehashing elements from Pulp Fiction (1994); Gladiator (2000) repeating elements from Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus (1960); and Avatar (2009) repeating Dances with Wolves (1990) and Pocahontas (1996).

Also, it’s important to note that we’re talking about the first screen version. While this category sympathizes with Mark Harris’ insightful piece “The Day the Movies Died,” there is one key difference: we will not punish a film for pre-existing in literary form (i.e. novel, magazine, short story). We will only punish those taken from previous screen versions, be they television screens (The Fugitive, Mission Impossible) or movie screens (Van Sant’s remake of Psycho). This is because we want to reward writers, directors and producers for finding that great new idea that has not yet been brought to life on screen. So, while The Grapes of Wrath, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Godfather all started as best-selling books, their screen versions still get top marks because they were the first of their kind on screen. The same would have applied to the book-to-movie adaptation of Gone With the Wind (1939), but it loses points because The Birth of a Nation (1915) had already explored similar territory on screen.

Clearly, older movies will have the advantage here. If that irks you, take solace in knowing that the next category strikes the balance. Besides, people should appreciate history. It’s the equivalent of being “well read.” As Scorsese said during the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award, “Movies are the memories of our lifetime. We need to keep them alive.” A certain Mr. Spielberg agrees:

Durability

While the previous category measures the historic, this category measures how well a film holds up today. To a certain extent, we as viewers must put on a set of “glasses” when viewing films from bygone eras and try to place ourselves in that time. However, I also think it’s important to acknowledge overly dated elements. There are a couple things for which I will never dock points.

To Spielberg’s point in the above video, I will never dock points for a film being in black and white. If you look at films like The Rules of the Game, Wild Strawberries, The Sweet Smell of Success, Raging Bull, Down By Law (below), Schindler’s List or Memento, the stark B&W contrast pops even more than color — that is, after it’s been properly restored to its original glory. The recent Blu Ray release of Citizen Kane shows exactly why Orson Welles once said, “Tell Ted Turner to keep his goddamned Crayolas away from my movie.” Thankfully, Turner’s fad of “colorizing” B&W films has failed. I refuse to exacerbate the stigma against non-color. It remains to this date a stylistic choice; not a dated element.

I also won’t dock points simply for a film existing in the contemporary setting when it was created. Double Indemnity will always look like Los Angeles in the ’40s, Breathless like Paris in the ’50s and The French Connection like New York City in the ’70s, just like Wedding Crashers will always look like D.C. in the 2000s. All movies serve as time capsules to their eras — sometimes defining a period like Easy Rider (1969). A pay phone here or a telegram there won’t be enough to lose points, just like the appearance of Facebook in The Social Network (2010) won’t be punishable 30 years from now. Old movies are supposed to have old cars, old fashions, old hairstyles and old figures of speech. If I were to dock points every time Bogart said “kid,” every time Mae West flaunted like a “dame,” every time Cagney called someone a “dirty copper,” I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the mirror. These become almost endearing qualities.

Instead, this category is meant to measure the distractingly dated elements. These things actually take you out of the viewing experience, and thus must be measured:

(a) The condition of the film print. I will do my best to track down the latest restored version of every film, but bear with me, as some are hard to come by. A faded film print like Intolerance (1916) or Metropolis (1927) may be beyond saving. This stresses the importance of film restoration. As Scorsese said during his AFI Lifetime Achievement Award, “The way I look at it, since I couldn’t have lived and made pictures during the Golden Age of Hollywood, the next best thing I can do is to try and make damn sure that their work is protected and preserved for the future generations of the world.” Proper film restorations can add so much to a film’s look and appeal, as we’ve seen with Vertigo (1958) and The African Queen (1951).

(b) Music that does not stand the test of time. This includes overdramatic music that signifies a major event happening, or the cheesy electronica scores of the ’70s and ’80s (Marathon Man, Witness, Halloween).

(c) Overdramatic acting, namely in silent films (The Birth of a Nation, The Big Parade).

(d) The “shock” value of horror films that has long since faded (the growls of Frankenstein, the blood of Suspiria, the stabbings of Psycho).

(e) Outdated modes of film technology, from distracting “rear projection” as characters drive in a car (Notorious, Marnie), to the absence of sound in silent films, requiring title cards to pop up every time a character speaks (The Gold Rush, Battleship Potemkin).

(f) Most importantly, the datedness of special effects. This includes the stop-motion of King Kong (1933); the tumbles in Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958); the mechanical shark of Jaws (1975); the space toys of Star Wars (1977); and the shadow demons of Ghost (1990). While these films get top marks in the Visuals category (see below), they lose points here. Meanwhile, films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) become all the more remarkable for the way they do not date. Who knows how The Lord of the Rings and The Matrix will look 20 years from now? My hunch is that, as effects progress, these too will date. Thus, this category forces filmmakers to question the need for special effects. It’s hands down the easiest way to date your movie — a short-term investment that will most likely come back to bite you.

Accessibility

Perhaps the most respected critic of all time, Pauline Kael, once said, “There is so much talk now about the art of the film that we may be in danger of forgetting that most of the movies we enjoy are not works of art.” It was she who also refused to watch the same movie twice, feeling she got all the necessary elements from an initial viewing.

I believe there is something to this notion of “enjoyment” and “first impression.” What is it, at a guttural level, that causes a viewer to tune out and yearn for something more familiar? How do we overcome this challenge? This question is the driving force behind this site; the spark that lit the fire to share my love of the “great” films, no matter how challenging. Instead of discounting this as an irrelevant phenomenon that only “dumbs down” society, we should call it for what it is, embrace it, and talk straight with our students and our readers.

“I’ll tell you right off the bat that La Dolce Vita is going to be a challenge for you,” we should say. “It’s three hours, has multiple storylines and ends with an ambiguous sea beast washed up on the shore. But here are all the cool things about it. Look at how Fellini shows the battle between sex vs. religion! Look at the pop culture impact, like inventing the term ‘paparazzi!’ And remember that episode where Homer Simpson hums that one catchy tune? Yeah, that’s Nino Rota’s theme to La Dolce Vita.”

This is how we reach the otherwise bored and apathetic people of my generation, by relating Big Jim’s “chicken” view of Chaplin in The Gold Rush to Newman’s view of Kramer in Seinfeld (more on this in “Pop Culture”), by pointing out the redeeming qualities of a Titanic or Avatar before explaining why they’re flawed, and by never talking down from a highbrow perch.

Thus, I hope the word “Accessibility” does not come across as condescending to filmmakers, like some sort of punishment for trying to push the envelope. Instead, it’s a measurement of a tangible phenomenon. If the goal of this site is to bring more mainstream folks to love cinema’s greatest works of art, “accessibility” is a challenge that’s impossible to ignore. To not talk about it is to continue a downward spiral of film elitism and film ignorance that continues to divide.

This is why I welcome both New York Times Magazine writer Dan Kois for his honest lament of slow movies as “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables,” and the crucial rebuttal by Times critics Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott, “In Defense of Slow and Boring.” The important part is that we continue to ask why such inaccessibility exists, to measure it, and overcome it. To paraphrase Denzel Washington in Philadelphia, “Let’s get it out in the open. … Let’s talk about what this case is really all about: the general public’s hatred, our loathing, our fear of [inaccessibility].”

There’s a reason why the average viewer sighs and rolls his eyes at the prospect of watching certain movies, and then gets bored and yawns while watching, as if to say, “I told you so.” Sure, sometimes it’s laziness and a lack of intellectual curiosity, but it’s also caused by tangible factors embedded in the films themselves.

Before we get to these, there are two quick disclaimers. First, I will keep this category separate from “Durability.” While a film’s datedness does contribute to a film’s inaccessibility, I will not dock points here because it has already been covered in “Durability.” There’s an important distinction here between the “old” and “inaccessible.” A fast-moving, hilarious silent film like Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) or Buster Keaton’s The General (1927) may lose points for “Durability” but will not for “Accessibility,” whereas the long, complex The Birth of a Nation (1915) or Greed (1924) will lose points for both.

Second, I will also not dock stars for language. While reading subtitles is at first painful, it would be unfair and impossible to punish a film for this, because everyone speaks a different language. Speakers of a film’s native language will always have a fuller experience than those who have to read before gazing, but we can all limit this inescapable fact by routinely watching as many different language films as possible.

Finally, I will not dock points for aspect ratios. While varying aspect ratios have caused gripes from “mainstream” viewers for years — “why are those stupid black bars at the top and bottom of the screen?” — they are there for a reason. They preserve the film’s original image size and better mimic our panoramic eye sight, as evidenced by the shift from square-shaped television (4:3 aspect ratio) to the widescreen format (16:9). Turner Classic Movies did a wonderful explanation in this video below:

Without further ado, here are the five accessibility factors I will measure in this category: complexity, ambiguity, oddity, boredom and length.

(1) Complexity. This includes films with numerous characters and plotlines (The Godfather, Nashville, Magnolia), unusual structures (Citizen Kane, Memento) and theme- or character-driven works (Days of Heaven, 8 1/2, Persona). Some films require a certain amount of life experience or historic and cultural knowledge to fully grasp, and even then, it can sometimes be tricky to piece the meaning together.

(2) Ambiguity. If a movie ends abruptly or cuts off unexpectedly (No Country for Old Men), it leaves mainstream audiences to say, “Wait, what? It’s over?” Call it the Sopranos Effect. Other times, everything is not tied up neatly, thanks to “unhappy endings” (the bus ride in Midnight Cowboy) or thematic symbols (the sea creature in La Dolce Vita). This can make first-time viewers feel like they’ve been gypped with a seemingly random conclusion, requiring a second look to uncover the significance. This dilemma reveals the difference between a “happy” ending and a “satisfying” one, and you may be surprised once you give a film a closer look.

(3) Oddity. This means all things quirky, weird and off the beaten path. Sometimes directors are bizarre with a hidden purpose and other times it seems they’re being bizarre for the sake of being bizarre. The films of David Lynch, Luis Bunuel and Wes Anderson are the first that come to mind. Some of us revel in this stuff, feeling that the weirder it is, the more fresh and fascinating. For the vast majority, however, it’s a turn-off that we must measure (and one that will be counteracted in the next category).

(4) Length. Films like Gone With the Wind (1939) or Doctor Zhivago (1965) might be labeled “hard to sit through” for their sheer scope and runtime. Other films are exceptions, and we watch them in spite of their length, films like Braveheart (1995), Titanic (1997) and The Shawshank Redemption (1994). Still, even if we love these movies, we can’t help checking our watches before we dive into Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Ben-Hur (1959), Patton (1970) or Schindler’s List (1993). William Wyler once said, “I have a theory: not to bore the audience,” Wyler said. “That’s a good theory. It sometimes seems that all pictures are too long, mine included, but this is always what I try to avoid.” (Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age)

(5) Boredom. This is that inescapable feeling where “not much happens.” This is the “slow movie” mentioned in the Dan Kois article above. Rest assured that most of the time, more is going on than meets the eye. Some filmmakers are deceptively simple, like John Cassavettes (A Woman Under the Influence) or Jim Jarmusch (Stranger than Paradise). Others are busy mining life’s hidden truths, through character studies (The Last Picture Show) and layers of symbolism (Citizen Kane).

When you add up all these factors, it’s clear this category measures the side of the spectrum that got us to love the movies in the first place, as kids; the side that ensures us as adults that we can say, “You gotta see that movie,” and know our mainstream family and friends will enjoy it. It’s the side that measures blind first impressions before any knowledge of critical film theory; the side that leads to such best lists as the AFI’s 100 Cheers and BRAVO’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments. Any filmmaker will tell you it’s just as hard to keep an audience riveted as it is to layer mise-en-scene, and I believe this to be the great under-explored area that makes directors like Hitchcock, Hawks, Wilder, Kurosawa and Scorsese so fascinating.

Scorsese himself admits to this in his A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese, describing directing as an eternal battle between “personal expression and commercial imperative.” Does this duality lead to a split personality, Scorsese asks? Does making films, or in our case writing about them, constitute cinematic schizophrenia, trying to balance simple entertainment with complex art?

Great names in film history have come down on both sides of the aisle. On the side of simple entertainment, director William Wyler said, “If you make a film that has something to say, if you want to convey that thought to a large audience, then you must make it compatible to them. You must make them accept it and like it. Otherwise, if they don’t come to see your picture, you only reach a handful of people, and you have not succeeded in getting your message across.” Likewise, Billy Wilder once said, “I go back to my penchant for the popular and successful picture. I just think that when people try to belittle The Exorcist or Jaws, I just think these people are crazy. Mr. Spielberg knows exactly what he did, and he did it brilliantly.” (Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age)

On the side of film as art, Gregory Peck had this to say in his AFI Lifetime Achievement Award speech: “Making millions is not the whole ballgame, fellas. Pride of workmanship is worth more, artistry is worth more. The human imagination is a pricelss resource. The public is ready for the best that you can give them. It just may be that you can’t make a buck and at the same time encourage, foster and commission work of quality and originality.” Likewise, King Vidor says viewers’ first impressions aren’t as important, claiming that a good film is like a fine wine, it just gets better and better with time. (Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age)

In the end, it comes down to a simple choice by the filmmaker, whether to go the experimental or commercial route, whether to please or challenge, whether to create art or entertainment. Fortunately, the two aren’t always mutually exclusive and have co-existed throughout movie history.

Look no further than the interplay between the mainstream George Lucas and the artful Francis Ford Coppola, two great friends whose careers are forever intertwined and who best sum up the “Accessibility” phenomenon.

“Francis works in a very intuitous way, so he likes to take advantage of things as he moves along through a picture,” said George Lucas, who directed the Coppola-produced American Graffiti (1973) and who was originally set to direct Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. “Francis just likes it to flow, and whenever you do that, you end up with a problem of having a film at times that is way too long and a film that doesn’t have a really strong narrative line in it that you can keep the audience hooked in.”

As the architect of Star Wars and co-creator of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lucas has made a career with “strong narrative lines” that capture the mainstream imagination. The more artistic Coppola was aware of this very issue.

“Nothing is so terrible as a pretentious movie, a movie that aspires for something really terrific and doesn’t pull it off is shit, it’s scum, and everyone will walk on it as such. And that’s why poor filmmakers, in a way, that’s their greatest horror, is to be pretentious. So here you are on the one hand, to try to aspire to really do something; on the other hand, you’re not allowed to be pretentious.

“Why don’t you say fuck it, I don’t care if I’m pretentious or not pretentious or if I’ve done it or haven’t done it, all i know is that I’m gonna see this movie, and that for me it has to have some kind of answers, and by answers I don’t mean just a punchline, but answers on about 47 different levels. It’s very hard to talk about these things without sounding corny. You use a word like self-purgation or epiphany, they think you’re either some kind of religious weirdo or asshole college professor, but those are the words for the process, this transmutation, this renaissance, this rebirth, which is the basis of all life.”

Direction

Coppola’s “47 different levels” (described above) are what I believe to be the essence of “direction” — a filmmaker’s personal vision and worldview expressed through symbolic, artful and stylistic means. Others throughout history have described it other ways.

Andre Bazin (What is Cinema?, 1950) describes it as the expression of a language unique to cinema, using a “whole arsenal of means whereby to impose its interpretation of an event on the spectator.” David Mamet (On Directing Film, 1992) says it boils down to two simple questions: what do I tell the actors, and where do I put the camera? And Lenore DeKoven (Changing Direction, 2006) says it’s the ability to articulate a thematic throughline.

Meanwhile, Stefan Sharff (The Elements of Cinema, 1982) describes it as the orchestration of various cinesthetic techniques, including separation (alternating two separate images in an A,B,A,B pattern), parallel action (intercutting two parallel tales), slow disclosure (gradually revealing something by withholding visual information), multiangularity (intercutting shots of various sizes from various angles), familiar image (repetition of visual motifs for emphasis and callback), moving camera or single take (camera moving through space or remaining fixed for long periods of time without cutting) and the Master Shot Technique (created by the Hollywood studio system for conversation scenes, starting with a “master shot” of two characters, then intercutting over-the-shoulder shots, then back to the master shot). The dreamer in me would like to consider this my humble link to Hitchcock, who mentored Sharff, who mentored Larry Engel, who mentored me. Of course, it’s a stretch, but let me have this one.

In keeping with this tradition, The Film Spectrum will approach things primarily from a film theory perspective. The bulk of this will be measured in the Direction category (my favorite of all the categories and the one theorists would argue is most important).

It’s important to differentiate the “art” and the “craft” of filmmaking. If someone were to walk onto a film set for the first time, he would witness the “craft” of filmmaking and gain respect for how much goes into it. However, understanding the “craft” does not mean understanding the “art.” Learning how to make films is but a stepping stone into how to make great films. Thus, it’s entirely possible to go to film school, learn how to physically achieve certain things, and still not know why you are achieving them.

The great films are ones you can dissect decades later and discover that they work on a higher plane of meaning. These films reveal the difference between a “strong” and “weak” director. The latter lets viewers float through the film for first-time experience alone, while the former applies a clear directorial vision to each and every frame.

The best way of saying this is the all-encompassing term mise-en-scene, posed by the French critics of Cahiers du Cinema to describe all elements of an image, including the entire frame (the 2D border) and the entire field (the 3D illusion of a foreground, middleground and background). Most filmmakers put years of thought and effort to imitate what the greats seemed to envision instinctually. I know this all sounds very abstract, but it will begin to make sense as we together analyze the great works of film history throughout this site.

When you consider such things about a particular filmmaker over a long period of time, we begin to touch on the “Auteur Theory,” first posed by Cahiers du Cinema and constantly tossed around by film buffs today. This theory posed the notion that we should judge a film in the context of its director’s entire body of work, looking for a consistent signature — comprised of recurring themes, styles and techniques. In this light, the merits of the film’s author (auteur) far outweighed the particular movie at hand. Thus, proponents of the theory claimed there were no bad films, only bad filmmakers.

While I don’t agree entirely — I do think there are bad movies — the theory is immensely helpful in assigning scores for this category. Through much research — reading past analyses, absorbing academic instruction and taking my own notes — The Film Spectrum is able to identify various “iconography” of individual filmmakers. Naturally, because theorists have spent so much time studying these auteurs (Welles, Hitchcock, Hawks, Godard, Fellini), I have more analysis to draw from, and thus award more points to these directors.

Even so, I will try my best to award “Direction” points on a case by case basis, judging clever and effective directorial techniques, even if that filmmaker does not yet have a large enough body of work to nail down trends. In other words, a movie can still get high marks for a great one-time directorial effort even if the rest of their work is lacking.

Also, not all famous directors will get top scores all the time. The most famous director of all time, Spielberg, will himself admit to being more of a commercial director, a great storyteller, but one who lacks an auteur style. While certain works of his deserve top marks (Jaws, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan), it’s enlightening to hear Spielberg compare himself more to Michael Curtiz (Casablanca) and Victor Fleming (Gone With the Wind) than Welles, Hitchcock or Scorsese.

I would be remiss not to mention how “editing” factors into this process. You often hear about John Ford editing in camera, or the fact that Alfred Hitchcock was always bored on set because he’d already seen the movie play out in his head while storyboarding. This is because a strong director visualizes story in terms of the edit: his/her “Director’s Cut.”

Elia Kazan emphasized a totalitarian approach: “I think editing is part of directing. That’s why I don’t like it when editors get the same credit that directors do. I think a director should do absolutely everything. I think the sets are his. The costumes are his. The editing is his. I’m a believer in the dominance of one person who has a vision.”

I admire Kazan’s all-encompassing vision, and agree that the end product should drip with a director’s purpose from image to image. Anything less is lazy on the part of the director. However, I believe his blanket statement undersells the important of the editor. After all, what would Raging Bull be without those choppy in-ring edits; Breathless without its pioneering jumpcuts; or Easy Rider without those acid-trip “triple intercuts” between scenes? Indeed, many of history’s greatest editors are synonymous with their director’s success: Hitchcock/Tomasini; Scorsese/Schoonmaker; Tarantino/Menke. As told in the documentary The Cutting Edge, editors sometimes even have to save the day, performing post-production magic while reassuring their weary director — a beaten shell of a man after an exhausting shoot — as Cambern did for Dennis Hopper on Easy Rider and Fruchtman, Greenberg and Murch did for Coppola on Apocalypse Now.

As such, this category rewards the result of this entire process: achieving the Director’s Cut.” This process provides the greatest window into film analysis because the edit is the fundamental building block of film theory. It is, in theory, a monumental tool at the director’s disposal, his authorship on every cut, and the editor his instrument in making that happen. Can you imagine splitting hairs between the editing job of Battleship Potemkin (1925) and the direction of Sergei Eisenstein? Impossible.

For more insight into the editing/directing relationship, check out the Kuleshov Theory. The notion works on the idea that the same image (that of a man’s face) can elicit three different meanings when intercut with three different images: a bowl of soup (hunger), a dead child (grief) and a sexy woman (lust).

Here’s Hitchcock’s take on this phenomenon:

The more familiar use of the term “Director’s Cut” is, of course, what you’ll see plastered on the side of DVD cases. This refers to the idea of restoring a director’s vision after studio executives have tinkered with the process, even to the point of re-editing the film. This will be taken into consideration, as I will try to judge Touch of Evil (1958) according to the restored version based off Orson Welles’ notes, just as I will try to judge Blade Runner (1982) for Ridley Scott’s Director’s Cut.

The studio’s commercial grip on a director’s artistic vision is a dilemma that continues today. Technology has brought a sea change in the industry, bringing enormous possibility, but also the danger of opening Pandora’s Box (Avatar pun intended). Filmmakers of the past like Coppola foresaw the coming of YouTube and digital cameras:

Coppola’s notion is that the more we strip down the commercial aspects of moviemaking, the closer we get to making art for art’s sake. To a great extent he is correct, albeit idealistic. This ideal can only happen if today’s filmmakers channel their newfound freedom and mobility through the prism of historic cinematic understanding. They must put in the time, learn the cinesthetic techniques at their disposal, engrain their film knowledge like walking almanacs, and, above all else, learn to see through the cinematic eye. I’m afraid this is happening less and less, taking us further from Coppola’s ideal, which is exactly why I find I launched The Film Spectrum.

My goal is to help you to learn what to look for in the hope that you’ll experience that wonderful eye-opening moment when you finally learn to see through the cinematic eye. If I, a mainstream jock from rural Maryland, can go off to college and have this epiphany while watching The Searchers, anyone can. Trust me, I am not that smart, nor that unique. I am just one in a whole century of people who have come to see film as something more. How wonderful that it can be learned.

Screenplay

While film will always be a director’s medium (whereas TV is more a writer’s medium and theater an actor’s medium), the foundation for any great movie is the script. In fact, if someone argued that the script is the most important part of movies, I really couldn’t argue with them. Afterall, this is the genesis of the idea — the great new text that producers and directors scour to find; the piece that gets the actors to sign on; and eventually the project’s calling card for financiers. I think it’s safe to say that no person in the film industry works harder mentally for so little credit as the screenwriter.

There’s something about the magical exchange that occurs between a screenwriter and his typewriter — or today with his computer (though most software like Final Draft maintains that nostalgic typewriter font). This is why I love what the Academy Awards have done the past few years by showing the text of the script over the image of the actors speaking the words. It helps to remind us that the story is written first.

This category seeks to celebrate the great screenwriters, from the Ben Hechts, Ernest Lehmans and Herman and Joseph Mankiewiczs of Hollywood’s Golden Age; to the William Goldmans, Woody Allens and Paddy Chayefskys of the renaissance; to the David Mamets, Aaron Sorkins and Charlie Kaufmans of today.

This category covers numerous elements: premise, characters, narrative structure, dialogue and theme.

(a) In terms of premise, I’m talking about the creative idea that sparks the entire story. For example, the idea of Shoeless Joe Jackson coming back to play baseball in an Iowa cornfield in Field of Dreams (1989). The idea of a killer who punishes by the seven deadly sins in Se7en (1996). The idea of technology that can erase a loved one from your memory in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

(b) In terms of character, I’m talking about a memorable and clearly identifiable character, including the protagonist (hero) and antagonist (villain). These often come with a flaw like Indiana Jones’ fear of snakes or George Bailey’s loss of hearing in one ear. This also comes with a character arc that charts the character’s progress through various scene needs (what they need to achieve in each scene), ultimately working toward an overall life need. For down-and-outer Rocky Balboa, that life need is to prove himself, as articulated in that great scene with him telling Adrian that all he wants to do is go the distance. This is why we cheer so loud despite his loss to Apollo Creed, because he has achieved his life need. For billionaire mogul Charles Foster Kane, the life need is to find his lost innocence, as articulated in his desire for his childhood sled “Rosebud.” This is why it’s such a tragedy when he dies alone, holding a deceptively simple snowglobe. For examples of great characters, check out Premiere magazine’s Top 100 Characters of All Time and the AFI’s Top 100 Heroes & Villains.

(c) In terms of narrative structure, I’m talking about the various “story beats” (or individual events) that occur throughout the film and how this is presented. This is usually broken into an A-Story and a B-Story. The A-Story is the main narrative thrust, the main journey, while the B-Story is a subplot that often winds up being more memorable. In Witness (1985), the A-Story is Harrison Ford’s crime mission which takes him to an Amish Country farm. However, we remember the B-Story of his relationship with Kelly McGillis. In Jerry Maguire (1996), the A-Story is Jerry’s career as a football agent for Cuba Gooding Jr. However, we most remember the B-Story, his “you complete me” relationship with Renee Zellweger.

Many books have posed different theories on screenplay structure. The godfather of these is Syd Field’s Screenplay, which greatly articulates the idea of a three-act structure.

Vikki King’s How to Write a Movie in 21 Days describes a “9-Point Clothesline:”

–P. 1 – Opening image (crucial—your first chance to hook the reader)

–P. 3 – Theme stated (state the central question/issue you will explore throughout the script)

–P. 10 – Catalyst (by now, you should have set-up everything and a catalyst sparks your story and overthrows the “ordinary world”)

–P. 30 – Plot Point One (a turning point happens that spins the story in a different direction; often a change in location as the hero embarks on journey)

–P. 45 – A moment that shows the character is growing/changing (also around this time, you’ll see the introduction of a B-Story, the love interest enters, etc.)

–P. 60 – Midpoint (the hero recommits further to his goal, often a mirror of the ending; if the end is unhappy, the midpoint is usually a moment of false hope; if the end is happy, the midpoint is usually a major setback; not always the case; some scripts have a midpoint that simply foreshadows the ending)

–P. 75 – How your hero has changed (the hero is about to give up, but he now responds to an event in a way that he wouldn’t have been able to at the outset of the film)

–P. 90 – Plot Point Two (your second turning point, sparks the race to the finish)

–P. 110-120 – Resolution (ideally, the closing image reflects your opening image)

Meanwhile, Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat has become immensely popular with screenwriting teachers with its Blake Snyder Beat Sheet (BS2). Despite its annoyingly cocky and commercial tone (I wanted to punch him when he said “screw Memento“), the book is a great way for beginners to learn to write for structure. After all, you need to know the rules before you can break them. Here’s how Snyder sees it:

–OPENING IMAGE – The scene in the movie that sets up the tone, type of project (intimate, medium or tentpole film), and initial salvo of images that establishes the “before” snapshot of the film’s situation.

–THEME STATED (by pg 5) – Usually spoken to the main character, often without knowing what is said will be vital to his/her surviving this tale. It’s what’s your movie’s “about.”

–SET-UP (pg 1-10) – The first 10 pages of your script must not only grab our interest — and a studio reader’s — but introduce or hint at introducing every character in the A-Story.

–CATALYST (around pg 12) – The telegram, the knock at the door, the act of catching someone in the act, something that’s done to the hero(ine) to shake them. The movie’s “whammy” that faces the hero with the new situation.

–DEBATE (pgs 12-25) – The section of the script, be it a scene or a sequence, when the hero(ine) doubts the journey he must take.

–BREAK INTO ACT TWO (around pg 25) – Where we leave the hero(ine)’s “normal” world behind, entering the “upside-down” world of the new situation. This is when the hero(ine) is motivated by an event that ends the debate and forces them to make a choice. Their journey begins.

–B-STORY (around pg 30) – Traditionally the introduction of the “love” interest, but cna more broadly be the moment where the character meets the person with whom the theme of the movie is discussed/mulled.

–FUN AND GAMES (pgs 30-55) – Here we enjoy the “promise of the premise,” the scenes and sequences where the hero(ine) dives into this new upside-down world and all its challenges. The part of the movie where most of the trailer’s clips are found.

–MIDPOINT (around pg 55) – The dividing line between the two halves of a movie that raises the stakes, where an obstacle forces the hero to recommit to his goal (usually with a “ticking clock” element introduced that puts the pressure of succeeding by a certain time, “or else”).

–BAD GUYS CLOSE IN (pgs 55-75) – A series of sequences where both internally (problems inside the hero(ine)’s team and with hero(ine) themself) and externally (as actual bad buys tighten their grip), real pressure comes down on our hero(ine).

–ALL’S LOST (pg. 75-85) – The “false defeat” and the place where death occurs (either literally or figuratively).

–DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL (pg. 86-90) – Where the hero(ine) loses all hope and faces the choices that brought him/her to this point.

–BREAK INTO ACT THREE (pg. 91-95) – Thanks to a fresh idea, new inspiration, epiphany, or last-minute action/advice from the B-Story character and/or love interest, the hero(ine) chooses to fight.

–FINALE (pg. 96-115) – From what was, and that which has been learned, the hero(ine) foreges a new way to succeed.

–FINAL IMAGE (p. 120) – The Opposite of the Opening Image, proving a change has occurred (should be a dramatic, noticeable change).

For examples of how this works in 10 famous films, check out these very helpful compilations put together by the Media Juice blog. Hats off, guys.

(d) In terms of dialogue, I’m obviously talking about a film’s spoken words. This includes the rapid-fire exchanges of Bringing Up Baby (1938) or His Girl Friday (1940); the countless memorable quotes from Casablanca (1942); the double-entendre battles of film noirs like Double Indemnity (1944) and Out of the Past (1947); the vastly different “words of wisdom” from The Godfather (1972) and Forrest Gump (1994); the pop culture musings of Diner (1982), Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994); and the voiceover narration of Sunset Blvd. (1950), All About Eve (1950), Apocalypse Now (1979), Goodfellas (1990) and The Shawshank Redemption (1994). See how many examples you recognize from the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes.

(e) Finally, every great script masters its theme. Some of these include the American Dream perverted in Citizen Kane (1941), The Godfather (1972) and There Will Be Blood (2007); the double-edged sword of war in Patton (1970), The Deer Hunter (1978) and Platoon (1986); the evils of racism in The Searchers (1956), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and Do the Right Thing (1989); the sexual freedom of The Graduate (1967), Harold and Maude (1971) and Brokeback Mountain (2005); expansion of the frontier in Stagecoach (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946) and Shane (1953). You get the idea.

It’s hard to believe so much goes into a single script. But it does. To read a well-written one is to hold gold in your hands. Check out the WGA’s Top 101 Screenplays of All Time.

Acting

Even great characters in a great script will mean nothing without great performances by the actors. It’s safe to say that the cast alone is the one true reason the public goes to a movie. Mainstream viewers don’t care about the writer, and most don’t care about the director. They go to see the familiar faces they live to love and love to hate.

What do we mean by a great performance? It’s Buster Keaton maintaing a stone face while risking life-and-limb on a moving train in The General (1927). It’s Katherine Hepburn hilariousy limping and saying, “I was born on the side of a hill” in Bringing Up Baby (1938). It’s Humphrey Bogart first “sticking his neck out for no one” then doing the most selfless and honorable thing to save the world entire in Casabalanca (1942). It’s Bette Davis chugging down a martini and prepping for the worst in All About Eve (1950). It’s Marlon Brando lamenting what could have been in On the Waterfront (1954). It’s Alec Guiness doing that proud wobbly-legged walk in front of his fellow British POW’s in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). It’s Paul Newman sinking balls in the corner pocket in The Hustler (1951). It’s Jimmy Stewart mining the depths of lost love in Vertigo (1958). It’s Meryl Streep recalling horrific concentration camp memories with a believable accent in Sophie’s Choice (1982).

It’s Gregory Peck bringing us to tears with his closing argument in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). It’s Peter O’Toole bringing an entire region to its knees with a single turn atop a train in Lawrence of Arabia (1962). It’s Catherine Denueve and Gena Rowlands going to their respective brinks of insanity in Repulsion (1965) and A Woman Under the Influence (1974). It’s Bill Murray doing play-by-play to his own garden tee-shot in Caddyshack (1980). It’s Robert DeNiro training toward a chiseled body in the boxing ring, then gaining weight for the same performance in Raging Bull (1980). It’s Anthony Hopkins terrifying us with a slithering tongue for fava beans and a nice cianti in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). It’s Daniel Day Lewis screaming he has abandoned his child in There Will Be Blood (2007). For more, check out Premiere magazine’s Top 100 Performances of All Time.

This category will likely score high most often, because often great performances are so crucial to great movies. That, and the best actors of the day want to work with the best directors, and thus are often in the best films together. Acting is often the first thing an audience notices, the first turn-off or turn-on as to whether they “buy into” the illusion. It also seems actors have such large bodies of work that they can afford to do more bad pictures than great ones because it keeps them working and keeps the money flowing. If you look through a list of an actor’s filmography, you’ll find a slew of stinkers. But it’s those gems — those pairings with great directors, great scripts, and great co-stars — that form our sense of their careers.

What would Jimmy Stewart be without Frank Capra? Cary Grant without Alfred Hitchcock? Mary Pickford without D.W. Griffith? Katherine Hepburn without George Cukor? Humphrey Bogart without John Huston? John Wayne without John Ford? Elizabeth Taylor without George Stevens? Diane Keaton without Woody Allen? Marlon Brando without Elia Kazan? Robert De Niro without Martin Scorsese? Anna Karina without Jean-Luc Godard? Marcello Mastroianni without Federico Fellini? Jean-Pierre Leaud without Francois Truffaut? Harrison Ford without George Lucas? Gena Rowlands without John Cassavettes? Johnny Depp without Tim Burton?

This category rewards the deep casts with stellar performance from top to bottom, films like All About Eve (1950) and The Godfather (1972). It rewards the performances by a director who comes in front of the camera, like Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (1941) or Woody Allen in Annie Hall (1977). It even rewards those films where the best performances aren’t by professional actors at all, like the father and son team in Bicycle Thieves (1948).

This category will try to judge acting in the context of each film’s era. For instance, prior to the 1950s, actors engaged in Classical Acting, and after, many preferred Method Acting. You can see this clash of styles in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), where Vivien Leigh’s traditional style shares the screen with Brando’s Method style. I will not take off points for dated overacting here, because this is already accounted for in “Durability.”

What to do about animated films? This category will try to award points for voice acting, like James Earl Jones in The Lion King (1994), Tom Hanks and Tim Allen in Toy Story (1995), Ellen DeGenerous in Finding Nemo (2002), and Robin Williams in Aladdin (1992). What about special effects characters and computer-generated films? I will try to award partial points to the voice for the title alien in E.T. (1982) and Gollum in The Lord of the Rings (2001). However, it wouldn’t be fair to give top points here compared to a live performance. Don’t worry — animated films will do better in the following category.

Visuals

This is the most all-encompassing category, rating a film’s wide-ranging aesthetic qualities; its entire visual look. This includes everything from lighting to cinematography, location scouting to set design, hair and make-up to wardrobe, props to vehicles, special effects to animation, graphics to credit sequences. Many of these are “theatrical” elements of the Art Department, like those found in a stage performance. Others are simulated contributions under the visual effects and animation departments. Others yet are organic (locations, landscapes). But all contribute to the visual look of the film:

(a) Lighting & Cinematography. The first thing people know about movies is the three word phrase: “lights, camera, action.” It’s no coincidence that these three all have to do with the magic of the camera itself. Lights illuminate the image, the camera records the image, and the action is captured in individual still frames that when viewed simultaneously create the illusion of motion. Hence, the term “motion pictures.”

All this falls under the giant umbrella of Cinematography. We must remember that film is first and foremost a photographic medium of film stock, sprocket holes, exposures, lenses, focus, depth of field, foregrounds, backgrounds, frame rates, aspect ratios, composition, framing, and techniques of light and shadow.

A film’s Director of Photography (D.P.) thus manages both lighting and camerawork, delegating the latter to a series of Assistant Camera operators and Dolly Grips, while delegating the former to the Gaffer (in charge of the lights) and Key Grip (in charge of items to block and control the light). The D.P. has final say over how all this is orchestrated, bringing to life the director’s overall vision.

How is all this measured on this website? It can be any number of things. The work of John F. Seitz on Double Indemnity and Gordon Willis on The Godfather will score high for their brilliant use of light and shadow. The work of Jean-Paul Alphen and Jean Bachelet on The Rules of the Game and Gregg Toland on Citizen Kane will score high for their brilliant deep-focus photography. The work of Karl Freund on The Last Laugh and Robert Burks on Vertigo will score high for their pioneering use of dollies and zooms. And the work of Sven Nykvist on Through a Glass Darkly, William Fraker on Rosemary’s Baby, Christopher Doyle on In the Mood for Love and Roger Deakins on No Country for Old Men will score high for masterful compositions. For help on what is meant by “great” lighting and cinematography, check out the AFI documentary Visions of Light.

(b) Special Effects. It’s important to note that, for better or worse, the line between cinematography and special effects continues to blur (another reason I’m grouping them together in the same category). This is thanks to 3D cameras that require the two to work hand-in-hand, or CGI models where a D.P. actually comes in to control the “computerized” camera in a 3-dimensional model where various “camera” vantage points are set up through powerful after effects and rendering software. For instance, the aforementioned Roger Deakins (Fargo) was brought as a visual consultant on WALL-E and How to Train Your Dragon, essentially doing his job as D.P. in an artificial computer world. Meanwhile, recent Oscars for Best Cinematography have gone to CGI-heavy films, i.e. to Mauro Fiore for Avatar (2009) and Wally Pfister for Inception (2010).

In addition to the contribution by the cinematographer, there are entire teams of special effects wizards who work magic for the screen. We’re talking about the stop-motion animation of King Kong (1993); the miniature model ships of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); and Dalton Trumbull’s spaceship descending over Devil’s Tower in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

We’re talking about Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) creating starships and light sabers for Star Wars (1977), amorphous water blobs for The Abyss (1989), liquid metal transformations for Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1992) and the dinosaurs for Jurassic Park (1993). We’re talking about even more recent achievements like the unsinkable cruise liner in Titanic (1997), the back-bending bullet dodges of The Matrix (1999), the battles with larger-than-life creatures in The Lord of the Rings (2001) and ultimately the 3-D worlds of Pandora in Avatar (2009).

Especially with special effects, it’s important to note that visuals will be judged upon their existence at the time. In other words, the outdated stop-motion effects of King Kong (1933) may lose points in “Durability,” but they will receive top marks here for being a groundbreaking visual masterwork for their time.

(c) Set Construction. Computer models are the only way to create an artificial world on screen. Physical set construction can be just as effective. Here, top ratings will go to such achievements as the German Expressionist sets of Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; Busby Berkely’s human waterfall in Footlight Parade (1933); the oversized windows and fireplaces of Xanadu in Citizen Kane (1941); the dream-sequence canals of Top Hat (1935) and An American in Paris (1951); the Technicolor rain puddle streets of Singin’ in the Rain (1952); the Greenwich Village apartment set of Rear Window (1954); the recreation of Mount Rushmore in North By Northwest (1959); and the eery futuristic streets of London in A Clockwork Orange (1971).

(d) Costumes. Here, top ratings to the Edith Head’s magnificent contributions to Hitchcock’s women; the trendy outfits of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1951); the unshakable alien suits of H.R. Geiger’s imagination in Alien (1979); and the fedora, satchel and whip of Indiana Jones. Costume dramas and period pieces have the clear advantage. However, it could also be as low-brow as the famous “COLLEGE” t-shirt in Animal House (1978) or those loud orange and blue suits in Dumb and Dumber (1994).

(e) Hair and Make-Up. This can include memorable styles applied to human characters, like Barbara Stanwyck’s symbolically phony wig in Double Indemnity (1944) or Kim Novak’s spiral bun in Vertigo (1958). This can also include extensive make-up jobs for other-worldly creatures in films ike Nosferatu (1922), Frankenstein (1931), Planet of the Apes (1968) and The Lord of the Rings (2001).

(f) Animation. This ranges from the classic cell animation of Disney on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), Sleeping Beauty (1959) and The Little Mermaid (1989); the brilliant anime of Mamoru Oshii in Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Hayao Miyazaki on My Neighbor Totorro (1988) and Spirited Away (2001); the computer renderings of Pixar in Toy Story(1995), Finding Nemo (2002), WALL-E (2008) and Up (2009); and the live action/animation combos, like Gene Kelly dancing with Jerry the Mouse in Anchor’s Aweigh (1945), Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke dancing with animated animals in Mary Poppins (1964) and Bob Hoskins handcuffed to Roger in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988).

(g) Graphics and Credit Sequences. This is all-too-often the forgotten element under the visual umbrella. What would James Bond be without those great opening credits? What would Hitchcock be without Saul Bass creating the spiraling opening credits of Vertigo (1958) or the symbolic splitting text of Psycho (1960)? These openings are almost reason enough to see these particular films, and I wish more films took advantage.

(h) Organic Elements. What about those filmmakers who rail against all these artificial and “staged” elements? Entire historical movements like Italian Neorealism and Dogme 95 have made it their mission not to use such things. Such films (Rome Open City; Breaking the Waves) will no doubt lose some points for their conscious choice to avoid “staged” elements. It’s a conscious choice that eliminates an entire segment of moviemaking by other talented artists whose work should be rewarded. If this seems unfair, don’t worry. Their decision to go this route is often made up for in the “Originality,” “Direction” and “Listology” categories, as historians adore the work of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica and Lars von Trier for this very reason.

Still, some points are possible, based on location scouting and the use of existing architecture and landscapes. Sometimes, organic settings will better serve the story than constructing a set. I’m talking about the Odessa Steps in Battleship Potemkin (1925); the Empire State Building in An Affair to Remember (1957) and Sleepless in Seattle (1993); the mountains in The Sound of Music (1965); the fountain in La Dolce Vita (1960); The Mouth of Truth in Roman Holiday (1963); the concentration camps of Schindler’s List (1993); the shores in The Piano (1993); the prison in The Shawshank Redemption (1994).

Soundtrack

While the visuals work magic on our eyes, the soundtrack works wonders on our ears. Dare I say it goes straight to the soul? This category measures a range of options, including original scores, soundtracks of existing song selections, original songs written for a particular film, and effective sound design.

(a) When it comes to original musical scores, top ratings go to those pieces that are instantly-recognizable. Consider Max Steiner’s Gone With the Wind (1939), Malcom Arnold’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho (1960), Nino Rota’s La Dolce Vita (1960) and The Godfather (1972), Elmer Bernstein’s The Magnificent Seven (1960), Monty Norman and John Barry’s 007 theme from Dr. No (1962), Maurice Jarre’s Dr. Zhivago (1965), Ennio Morricone’s The Good, The Bad & The Ugly (1966), Isaac Hayes’ “bad-mother-shut-your-mouth” swank in Shaft (1971), John Carpenter’s creepy piano theme from Halloween (1978), Thomas Newman’s triumphant theme from The Natural (1984), Alan Silvestri’s upbeat Back to the Future (1985), Danny Elfman’s magical Edward Scissorhands (1990), James Horner’s Scottish strings in Braveheart (1995), Quincy Jones’ shaggadelic theme for Austin Powers (1997), Clint Mansell’s harrowing Requiem for a Dream (2000), Howard Shore’s transcendent score from The Lord of the Rings (2001) and the master of the popular scores John Williams on Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), Superman (1978), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial (1982), Home Alone (1990), Jurassic Park (1993) and Schindler’s List (1993).

(b) Top ratings also go to those regarded by other film composers as masterworks, even if the average person may not know them by heart — Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), Max Steiner’s King Kong (1933), Eric Wolfgang Korngold‘s The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Sea Hawk (1940), Bernard Herrmann’s Citizen Kane (1941), Vertigo (1958), Cape Fear (1962) and Taxi Driver (1976), David Raksin’s Laura (1944), Franz Waxman’s Sunset Blvd. (1950) and A Place in the Sun (1951), Leonard Bernstein‘s On the Waterfront (1954), Miklos Rosza’s Ben-Hur (1959), Maurice Jarre’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Elmer Bernstein’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Jerry Goldsmith’s Patton (1970), Chinatown (1972) and The Omen (1976), Carter Burwell’s Fargo (1996) and Ennio Morricone’s The Untouchables (1987) and Cinema Paradiso (1988).

(c) Top ratings can also go to film scores that rework old instrumental ditties that have since become synonymous with their film use — “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), “Dueling Banjos” in Deliverance (1972),”The Entertainer” in The Sting (1973), “Tubular Bells” in The Exorcist (1973), “Carnival of the Animals” in Days of Heaven (1978), “Ride of the Valkyries” in Apocalypse Now (1979), “Cavalleria Rusticana” in Raging Bull (1980) and “Adagio for Strings” in Platoon (1986). For a better idea of which scores are considered great, check out the AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores.

(d) Some films include wall-to-wall soundtracks written almost exclusively for that film — Simon & Garfunkel on The Graduate (1967), Cat Stevens on Harold and Maude (1971) and the Bee Gees top-selling soundtrack of all time on Saturday Night Fever (1977). What would Dustin Hoffman’s lazy pool days be without “The Sounds of Silence” or his speeding car without “Mrs. Robinson?” What would Bud Cort’s opening suicide attempt be without “Don’t Be Shy?” And what would Travolta’s strut down a New York City sidewalk be without “Stayin’ Alive” or his disco moves without “You Should Be Dancing?”

(e) Other films include wall-to-wall soundtracks of an array of existing popular songs, strung together in an extension of the director’s vision — Easy Rider (1969), American Graffiti (1973), Mean Streets (1973), Apocalypse Now (1979), Top Gun (1986), Goodfellas (1990), Pulp Fiction (1994) and Forrest Gump (1994). These are soundtracks we know by heart, whose songs instantly call to mind scenes from those movies. Can you imagine Steppenwolf’s “Born to Be Wild” without Fonda and Hopper flying across the mid-west on those bikes? Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” without Wolfman Jack spinning tracks for Mel’s Diner? The Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” without De Niro’s slow-motion strut into the bar with a girl on each arm? The Doors’ “The End” without Coppola’s helicopters dropping napalm on a Vietnamese jungle? Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” without that slow push in on De Niro’s cold eyes? Chuck Berry’s “You Never Can Tell” without John Travolta and Uma Thurman doing the twist at Jack Rabbit Slims? Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” without Jenny standing on a balcony contemplating a suicide leap?

(f) Other times it’s a single song that has come to represent the film — “As Time Goes By” in Casablanca (1942), “Buffalo Gals” in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), “Do Not Forsake Me” in High Noon (1952), “I Wanna Be Loved By You” in Some Like it Hot (1959), “Moon River” in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), “Goldfinger” in Goldfinger (1963), “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” in Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969), “Everybody’s Talkin’ at Me” in Midnight Cowboy (1969), “The Way We Were” in The Way We Were (1973), “Amoreena” in Dog Day Afternoon (1975), “Gonna Fly Now” in Rocky (1976), “Old Time Rock n Roll” in Risky Business (1983), “I Put a Spell on You” in Stranger Than Paradise (1984), “The Power of Love” in Back to the Future (1985), “In Dreams” in Blue Velvet (1986), “Danger Zone” in Top Gun (1986), “Fight the Power” in Do the Right Thing (1989), “The Streets of Philadelphia” in Philadelphia (1992), “My Heart Will Go On” in Titanic (1997) and “Jai Ho” in Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Check out the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Songs.

(g) Most obvious are cases those songs written for musicals — “We’re in the Money” from Golddiggers of 1933 (1933), “Dancing Cheek to Cheek” from Top Hat (1935), “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz (1939), “White Christmas” from Holiday Inn (1942), “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” from Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), “Our Love is Here to Stay” from An American in Paris (1951), “Singin’ in the Rain” from Singin’ in the Rain (1952), “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” from Gentleman Prefer Blondes (1953), “Luck Be a Lady” from Guys and Dolls (1955), “I Could Have Danced All Night” from My Fair Lady (1964), “Shall We Dance” from The King and I (1956), “Tonight, Tonight” from West Side Story (1961), “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music (1965), “Don’t Rain On My Parade” from Funny Girl (1968), “Consider Yourself” from Oliver! (1968), “Cabaret” from Cabaret (1972), “You’re the One That I Want” from Grease (1978), “Beauty and the Beast” from Beauty and the Beast (1991), “The Circle of Life” from The Lion King (1994), “Come What May” from Moulin Rouge! (2001) and “All That Jazz” from Chicago (2002). Check out the AFI’s Top 25 Movie Musicals.

(h) This category also rewards exceptional cases of sound design. Some films have little to no score, but these films can still score well in this category if the choice for no music works effectively. For instance, Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), a film about electronic surveillance, makes brilliant use of electronic sound effects that practically become the soundtrack. Other examples include the sound of helicopters set to the blades of a ceiling fan in Apocalypse Now (1979), or the mixing of animal sounds as dinosaurs in Jurassic Park (1993).

I have gained an enormous amount of respect for the work that goes into sound design, mostly thanks to American University professor Russell Williams, who won a pair of Oscars as the sound recordist on Glory (1989) and Dances With Wolves (1990). I fondly remember standing in his office, picking his brain, and seeing the pride in his eyes as he recalled his time on Field of Dreams (1989) and the director’s secret delivery of the line: “If you build it, he will come.” Sometimes sound alone can have a major cultural impact.

Popular Culture

As expressed in its very title, this category includes both the popular and the cultural. The popular is measured in box office and video rentals, with the former measured in adjusted box office gross, meaning adjusted for inflation. The cultural includes all those references that we know by heart.

If Swarzenegger says, “Hasta la vista, baby” and the whole world starts saying it, The Terminator scores top marks. If Clint Eastwood says, “Go ahead, make my day,” and President Ronald Reagan quotes it, the Dirty Harry movies get top marks.

This also includes elements we’ve come to use so much in our collective culture that we’ve forgotten they come from the movies. Let’s not forget that “Fasten your seatbelts” comes from All About Eve (1950) and “You talkin’ to me?” from Taxi Driver (1976). Hell, the very phrase “paparazzi” comes from La Dolce Vita (1960). Now that’s cultural power.

Obviously, culture references aren’t limited to quotes. They also include references in other films, TV, music videos, advertisements, multimedia and web content. In each review, I will include a few select references I have found amusing over the years.

Cultural references also show up in other areas of society, from fashion to technology. This includes Audrey Hepburn donning Tiffany’s jewelry in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1951), Tom Cruise sporting aviator sunglasses in Top Gun (1986), and Apple modeling its iPod after the Monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Throughout all of this, I must admit a sliver of ethnocentrism. I’ve only ever lived in the United States, and while I do my best to study other cultures, there’s no way to completely eliminate, at least on a subconscious level, some sort of bias. I will do my best to judge this category from the standpoint of world pop culture, but even that has been largely influenced by American culture. Whether it’s the Taliban banning DiCaprio haircuts because so many young Afghan boys wanted to look like Leo in Titanic, or Parisian filmmakers like Godard and Truffaut obsessing over Bogie, Hollywood has historically set the tone for cinematic pop culture for more than a century.

However, keep in mind that some of the very best Hollywood filmmakers are natives of other countries — Hitchcock, Murnau, Lang, Kubrick, Wilder, Polanski, Lubitsch, Jackson, Boyle — so even Hollywood-created culture refelcts the best the world has to offer.

There have also been great examples of films from world cinema that have gained world pop culture status, films like Battleship Potemkin (inspiring the falling baby carriage of The Untouchables and The Naked Gun), Metropolis (creating the template for C-3PO), Bicycle Thieves (Pee Wee Herman jacking a bicycle with Tim Burton), The Seventh Seal (a chess match with death), The Seven Samurai (The Magnificent Seven), The Good, The Bad & The Ugly (that wailing theme song), Oliver! (all the songs), 2001: A Space Odyssey (HAL 9000), Blow-Up (spoofed in Austin Powers), Monty Python & The Holy Grail (any number of jokes), The Lord of the Rings (grossing millions at the box office), and Godzilla (no explanation needed).

Whatever unfortunate/unintended bias there may be, it’s no more slanted than best lists compiled by the likes of Leonard Maltin (89% English-language films) or Rolling Stone‘s Peter Travers (81% English-language). Such is the unavoidable fate of American-based sites written on English keyboards.

Listology

While the previous category measures box office receipts and pop culture impact, this category measures the superlatives and critical acclaim. Like ESPN has its “bracketology” for the March Madness tournament, we will engage in “Listology” — the study of a film’s place on a range of best lists.

A number of lists will be considered in this category, most notably the Sight & Sound international critics poll and the American Film Institute’s “100 Years” series. We’ll also examine best lists by Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, TIME, TV Guide and Vanity Fair. We will also examine fan polls like IMDB and Empire magazine.

Even if a film received poor reviews in its day, it can still get top marks if it has been reassessed as a masterpiece (i.e. Citizen Kane, Vertigo). Any film can be lauded in its own time, showered by awards while being swept up in the buzz of the moment. But hindsight is 20/20. Here, the test of time matters. That’s why this category measures how much films are acclaimed on best lists today.

Let’s face it: it’s not just good reviews that make Citizen Kane so renowned among academics — it’s the film’s hold atop lists like Sight & Sound and the AFI Top 100. The most elite best lists will obviously carry the most weight, but other niche lists will factor in, like BRAVO’s 100 Funniest Movies, ESPN’s Best Sports Movies, Maxim’s 100 Greatest Guy Movies, or the AWFJ’s Top 100 Films (from a woman’s perspective). You can find these best lists on our rankings page.

I can hear some of you saying: but aren’t most of these lists geared toward older films? What if the list came out before a certain film was even released? Isn’t it unfair to punish it just for that? I hear your concerns, but this disadvantage is duely balanced by an advantage in “Durability” and “Popular Culture,” as newer films have a better chance of appealing to current audiences and being referred to in current pop culture.

Granted, I will give newer films some opportunities to earn points in this category, like making a critic’s list of “The Year’s 10 Best;” surging to the top of the IMDB Top 250; earning high ratings on aggregate sites like rottentomatoes.com and metacritic.com; or picking up bigtime awards at the Oscars, Sundance or Cannes. However, such things will only earn a maximum of 2 stars in this category. Why?

Because this category is meant to separate the legends from those untested films that may soon fade. Who’s to say the current Oscar contender for Best Picture will not fade into the next Cavalcade? Never heard of that movie? Case in point. We’re taking a longview here. You have to earn your status as a listology classic.

Besides, that’s part of the fun of this site — the longevity of our relationship together as author and reader. Not only will we have our week-to-week dialogue, we’ll have the additional gift of reopening discussion every five years or so, when various publications revamp their best lists. In this way, we will track movements across eras, generations, even lifetimes. Looking forward to it.

Those are the ground rules, subject to change. With all due respect to critic Pauline Kael, who insisted on seeing movies only once, I have a policy not to review a film unless I’ve seen it more than once. Repeat viewings of these films and the release of new films will allow these opinions to evolve, but that’s the great thing about the internet. Nothing is set in stone. I hope this will be an ongoing discussion that is forever malleable.