Director: William Wyler

Producer: Samuel Goldwyn (Samuel Goldwyn)

Writers: Robert E. Sherwood (screenplay), MacKinlay Kantor (novel)

Photography: Gregg Toland

Music: Hugo Friedhofer

Cast: Fredric March, Myrna Loy, Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, Harold Russell, Virginia Mayo, Cathy O’Donnell, Hoagy Carmichael, Gladys George, Roman Bohnen, Ray Collins, Minna Gombell, Walter Baldwin, Steve Cochran, Dorothy Adams

![]()

Introduction

Every Thanksgiving night, Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) airs on national television, deserving a place in our hearts as an American classic. Ironically, far fewer people have seen the movie that beat it for Best Picture, The Best Years of Our Lives. This fact would sadden the film’s sole producer, Samuel Goldwyn, who said, “I don’t care if it doesn’t make a nickel. I just want every man, woman and child in America to see it.”

Indeed, it was crucial for a nation to collectively watch this 1946 post-war epic after the shared experience of returning from World War II, as the flickering light of a film projector helped Americans work through their fears, memories and permanent life changes. It could provide the same therapy for today’s veterans — if more people knew about it.

So to borrow a phrase from today’s kiddies, Goldwyn was a “G.” In fact, he was the “G” in MGM, and Best Years was his last with director William Wyler (Ben-Hur, Roman Holiday), who often fought with him over whose name would be placed higher on the billing. It was also their most successful together, winning seven Oscars, including Best Director for Wyler and Best Picture for Goldwyn, who that same year accepted the Irving Thalberg Memorial Award, which Wyler would himself win 20 years later.

![]()

Plot Summary

The film interweaves the “coming home” stories of numerous men as they return home to their women in the fictional post-war American town of “Boone City,” shot in Cincinnati, Ohio, after screen-testing aerial photographs of dozens of American towns. (A)

Alcoholic Army Sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March) struggles to reconnect with his wife Milly (Myrna Loy) and kids, whose pre-war photos no longer show any resemblance.

Air Force bombadier Fred Derry (Dana Andrews) struggles with both unemployment and shifting feelings of the heart. He finds himself in a love triangle between his party animal wife Marie (Virginia Mayo) and Al’s sweet daughter Peggy (Teresa Wright).

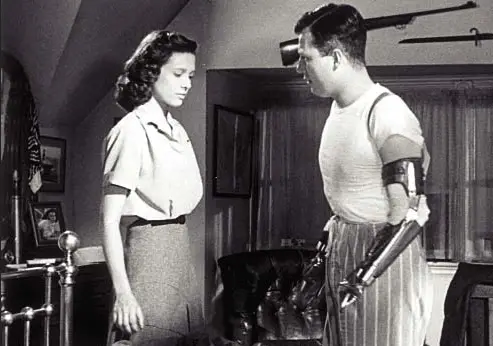

But the biggest struggle faces Sailor Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), the hometown football hero who lost both arms in battle, now replaced by hooks. He struggles with the embarrassment of performing simple tasks and worries he can no longer show proper affection for his fiancee, Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell).

![]()

The Best Script of Our Lives

So how did such a story come about? In 1944, Goldwyn read a story in Time magazine that discussed problems facing a group of ex-marines upon returning home from the war. Goldwyn placed a call to MacKinlay Kantor, a novelist who just returned from duty as an Air Force correspondent, and asked him if he would write a treatment based on the magazine article. Kantor agreed, and though a treatment would typically consist of 50 or 60 pages, Kantor came back with 434. Of course, this was much more than a treatment, and was published as a novel, Glory for Me, written in blank verse poetry.

At this point, Goldwyn asked Robert E. Sherwood, a Pulitzer Prize winning author and speechwriter for FDR, to adapt Kantor’s novel into a script. Sherwood, Goldwyn and Wyler held conference for days discussing the story before a single line of the script was written, and by the time the script was finished, it was so different from the original version that a publishing company offered to print a novelization of the film. It, too, won an Oscar, and the Writers’ Guilds recently voted it the #44 Greatest Screenplay of All Time, one spot ahead of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). (A)

![]()

The Best Cast of Our Lives

With such a powerful script, so obviously appealing to post-war emotions, it was a project tailor-made for emotional performances. And despite a reputation as “40-Take Wyler” — with such limited feedback as “Let’s do it again” or “Print it” — Wyler was the perfect actor’s director to realize it. His style never showed them up visually, never disturbed their process and always played to their strengths. It’s proof enough that throughout his career, Wyler directed a total of 39 actors to Academy Award nominations. (C)

The Best Years of Our Lives accounted for two of those nominations and marked the Oscar comeback of Fredric March, who took home the prize for Best Actor. He had won his first Oscar a full 14 years earlier with his powerful performance in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). He followed that with strong work in The Road to Glory (1936), Nothing Sacred (1937) and the original A Star is Born (1937), playing the drunken role of Norman Maine made famous by James Mason in the 1954 remake.

The inebriation prepared him for a hilarious sequence in Best Years, where March goes on a bender with his war-time buddies. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther called it “the best acting job he has ever done.” (B) Actress Shelley Winters (A Place in the Sun) later described the charisma that made March so lovable: “He was able to do a very emotional scene with tears in his eyes and pinch my fanny at the same time.” (B)

Standing strong right next to March is on-screen wife Myrna Loy, who gained fame as the Nora to William Powell’s Nick Charles in The Thin Man series (1934-1945). Throughout the war, she worked for the Red Cross and only made one film during during that time, The Thin Man Goes Home (1945).

As for their on-screen daughter, Teresa Wright is one of the real treats in classic American movies. She had debuted with Wyler five years earlier in The Little Foxes (1941) and returned with him for the Best Picture winner Mrs. Miniver (1942), where she won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. She then expanded her talents as Young Charlie in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and played Lou Gehrig’s wife in The Pride of the Yankees (1943). Still, her best role might be in Best Years, where her love story with Dana Andrews commands viewers attention.

Of course, part of the credit belongs to Andrews, who was fresh off such classics as The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) and Laura (1944). His performance should also have earned an Oscar nomination, as he so accurately captures a man torn between his post-war feelings for Wright and his pre-war feelings to Virginia Mayo, appearing three years before White Heat (1949).

The film even provides an appearance by Hoagy Carmichael, two years after appearing in To Have and Have Not (1944). Carmichael was a legend in his own right, having penned such classics as “Georgia on My Mind” and “Stardust,” the most-recorded American song ever written.

Still, ahead of all of these A-list music and movie stars, the first person cast was a non-actor, Harold Russell. While training paratroopers during the war, Russell had TNT explode in his hands, requiring a pair of mechanical hooks to be installed. In the original script, his character is a shell-shocked sailor, or as Wyler put it, “a spastic.” (C) But after Wyler saw Russell in the army training film Diary of a Sergeant, he and Goldwyn asked Sherwood to re-write the script to make the character a war vet struggling with his loss of hands. (A) The addition of an actual double amputee added to the film’s credibility, as Wyler could undress him and show that he really was missing his hands.

“Well, I’ve always believed that acting is a business that you have to learn. It isn’t something you can just pick up,” Wyler said. “Naturally there were problems with Harold’s acting, but I didn’t have to explain to him how it feels to lose your hands; he knew better than I. But there was the problem of making him feel and react in certain ways at a certain time with a lot of lights and cameras, which is not conducive to feeling or showing emotions. I had to treat him a little better than I do professional actors, by putting on my kid gloves.” (C)

The result was golden, literally, as Russell became the first disabled actor ever to win an Academy Award. It was an honorary Oscar for “bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans” and given to him because he was almost certain to lose Best Supporting Actor to Claude Rains for Notorious (1946) or Clifton Webb for The Razor’s Edge (1946). However, when the envelope was opened, it was Russell who took to the stage again, reduced to tears at the podium by the thundering reception. To this day, it remains the only time an actor has won two Oscars for the same performance. Looking back, the performance remains rather average, and Russell stayed away from acting for decades until Inside Moves (1980) and Dogtown (1997), devoting most of his life to helping other war veterans. (B)

![]()

Veteran Authenticity

In addition to casting Russell, Wyler continued his quest for authenticity by hiring only WWII veterans for his crew, all the way down to the grips, mixers and prop masters. (A) Screenwriter Kantor had served time as an Air Force correspondent, editor John Sturges (future director of The Great Escape and The Magnificent Seven) served in the Air Force, and the film’s narration was written by Lester Koenig, an air force sergeant. (C)

Most importantly, Wyler himself had gone into the Army Air Corps, where he spent almost four years flying combat missions and producing the war documentaries Memphis Belle and Thunderbolt. (A) The former followed an American crew flying 25 missions over Italy and Germany, during which Wyler lost his hearing in one ear like a regular George Bailey. (C) Those experiences helped him better understand the characters in Best Years.

“The film is one of the most successful films I ever made, and it was also one of the easiest,” Wyler said. “The reason is that I had been in the service myself. I came back from the war and had a few of the problems veterans have in getting readjusted. I understood these men very well. I had spent four years in research, so to speak, and knew these men better than Ben-Hur or Roman soldiers. I didn’t have to think, ‘Now, what would a man do in that situation?’ because I knew the situation. I knew the men. It made me think that very often we do pictures where we don’t know our characters well enough.” (C)

Occasionally, this real-life experience would lead him to deviate from the script. This occurred with one particular scene where Andrews walks around the airfield seeing the many obsolete airplanes that never got flown in the war. According to Wyler, “The script orginally said, ‘He walks around thinking of how the war had done him in.’ But because I did The Memphis Belle and rode in a bombadier’s compartment on a few missions, I got the idea that he would climb up into his own plane and have a dream and lose himself in the dream, or rather in hallucination. It was all invented on the spot because the airfield, those obsolete planes, were conducive to the basic idea of the film, of the man feeling lost.” (C)

![]()

Wyler & Toland: Directing & Lighting

Wyler’s own experiences as a married man away from home for the war created the film’s best scene where March returns home to his wife and family for the first time since the war. As March opens the door, the kids can barely contain their excitement, while his wife calls out from the other room, “Who is it?” before stopping in her tracks.

“She just stiffens up. She doesn’t say a word. And it’s one of the most beautiful family love scenes I’ve ever seen,” said director William Friedkin (The Exorist, The French Connection). “One of the three or four best scenes I’ve ever seen.”

This scene in particular made great use of Gregg Toland’s deep-focus photography, as we linger with the two children in the doorway foreground, watching March and Loy embrace deep in the background. Such deep-focus photography had made Toland a legend five years earlier on Citizen Kane (1941).

He never again worked with Welles, but teamed with John Ford on The Long Voyage Home (1940) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940). Wyler became Toland’s most prolific collaborator, working together seven times: Come and Get It (1936), These Three (1936), Dead End (1937), Toland’s Oscar-winning job on Wuthering Heights (1939), The Westerner (1940) and The Little Foxes (1941).

The Best Years of Our Lives would be their last together, and it’s a fitting culmination, as critic Jonathan Rosenbaum called it “one of the best things [Toland] ever did.” (D) Toland died of a heart attack just two years later at the age of 44, and Goldwyn was furious that no actors attended his funeral, the very actors he had made look so good. (F)

Indeed, it’s Toland who deserves most of the credit for the visual splendor of Best Years. While Wyler was extremely accomplished in his day, he in hindsight appears far less daring than his peers. He will himself admit he was no auteur: “When directing scripts by Lillian Hellman or Bob Sherwood, Sidney Kingsley or Jessamyn West, I could hardly call myself an auteur. However, I’m one of the few directors in town who can pronounce the word correctly.” (C) Such a joke does lend credence to David Lean’s comment on Wyler: “He had all the qualities a great director needed. He was both a dreamer and intensely practical — and he had a sense of humor about himself.” (C)

Even if you consider Wyler as something less than an auteur and something more like a prolifically capable Michael Curtiz, The Best Years of Our Lives may very well be his best directed film. It won him his second of three Oscars for Best Director, following Mrs. Miniver (1942) and preceding Ben-Hur (1959). Billy Wilder went as far as calling Best Years “the best directed film I’ve ever seen in my life,” and Sidney Lumet voted it his own favorite film of all time when polled for the latest Sight & Sound director’s poll. (B) Either way, the film is a triumph in pacing, which was one of Wyler’s strongest suits. The damn thing runs almost three hours, but it moves so fast, that you’d never know. It’s constantly engaging and never once boring.

“I have a theory: not to bore the audience,” Wyler said. “That’s a good theory. It sometimes seems that all pictures are too long, mine included, but this is always what I try to avoid. … To insist on length when it is not necessary is wrong. If you make a film that has something to say, if you want to convey that thought to a large audience, then you must make it compatible to them. You must make them accept it and like it. Otherwise, if they don’t come to see your picture, you only reach a handful of people, and you have not succeeded in getting your message across.” (C)

![]()

The Message

Here, the message is clear — to expose the hardships of veterans who lost “the best years of their lives” to war, who no longer recognize their lives upon their return, and who must somehow reshape their “new normal” to become the true “best years of their lives.”

While The Big Parade (1925) and All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) had explored the departure for war and the horrors of fighting it, Best Years was the first to focus exclusively on the aftermath. In this way, it’s the original precurosr to such Vietnam films as Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978) and Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989). When Best Years was re-released in 1954, it took on a whole new meaning for vets returning from the Korean War. (A)

Veteran Care. The conflict between the horrors of war and the pride of patriotism will exist as long as war itself, and thus Best Years will always be relevant. Watching the vets struggle back home is therapeutic for actual veterans, and a vicarious experience for civilians. As March, Andrews and Russell share a cab for the first time since the war, one says, “Feels like we’re going in to hit a beach.”

In a way, they’re right, as each goes through his own private hell. March fights injustice to become the voice for G.I.’s needing loans; Andrews suffers from post traumatic stress and nightmare flashbacks; and Russell struggles to fit back into a society where hands are a precious commodity.

Disabilities. The latter exploration is the most memorable, as Russell tries constantly to prove he’s no different than anyone else. When Russell signs paperwork, a guy suggests, “I’ll do it for you,” to which Russell replies, “What’s the matter? Think I can’t spell my own name?” As the film progresses, we see him play the piano, carry bags, drink beers, light cigarettes, shoot a rifle and shake hands. Still, no matter how defiant, he’s just as self-conscious. “They keep staring at these hooks, or staring away from them,” he says, in a moment of guilt that causes his family members to hide their own hands in his presence.

Class. The film also explores issues of class through the different experiences of the three male leads. During the war, they are all best buds fighting for a common cause. After the war, each comes home to different class circumstances — upper-class (March), middle-class (Russell), lower-class (Andrews). When they meet and carouse in the bar, it’s a reminder that we can all come together, regardless of class. (D)

Gender. The film also explores issues of male-female relationships, with a number of female characters who “stand by their man,” but who actively pull them out of their war-tainted flaws. Not only was the film the first to have a disabled actor in a major role, it was also one of the first to deal with intimacy issues between disabled and non-disabled lovers. (A) This made some uncomfortable at the time, as critic Robert Warshow resented the “challenged masculinity” of Russell, as did humorist Terry Southern. (D)

Politics. One of the most intriguing things about the film is how it’s garnered such varied responses from so many political points of view, both in 1946 and today. Critic Manny Farber called it “a horse-drawn truckload of liberal schmaltz,” (G) while film scholar David Thomson called it “a sweet, conservative dream.” (F) Depending on your preconceived political notions, you can either cheer or jeer the film through red or blue colored glasses. But the real truth is often the color purple, so I prefer to view it as both a conservative tribute to strong family values and a progressive critique of unchecked patriotism overlooking the needs of the poor and disabled.

![]()

Legacy

Beyond politics, the film initially garnered mixed reaction. Crowther wrote, “It is seldom that there comes a motion picture which can be wholly and enthusiastically endorsed not only as superlative entertainment but as food for quiet and humanizing thought.” (B) Meanwhile, Pauline Kael ripped it, saying, “Despite its seven Academy Awards, it’s not a great picture; it’s too schematic and it drags on after you get the points…however, there’s something absorbing about the banality.” (B) If you’re like Kael, and don’t like being hit over the head with things, you may not like Best Years. Film has certainly evolved in its subtlety since the 1940s. But if you like neatly structured movies, packed with emotion and a nostalgic touch, you’re gonna love this movie.

Best Years certainly has an appeal to the masses. It was a monster box office hit in 1946, grossing $23.6 million (H) to become the most successful movie since Gone With the Wind (1939). (I) Mainstream viewers who have seen it today also seem to agree, voting it #171 all time on IMDB — one spot ahead of The Avengers (2012).

As for the experts, most have overlooked any lingering flaws, ranking the film #11 on the AFI’s 100 Most Inspirational Movies of All Time, just ahead of Apollo 13 (1995) and just behind Saving Private Ryan (1998), while holding firm at #37 on both editions of AFI’s Top 100 Films. To me, The Best Years of Our Lives is one of those great balances between art and entertainment, leaning more towards the entertainment, for sure, but distinctively gorgeous to look at and imbued with utmost social significance. What’s more, the film now serves as a time capsule for an important period of American history. It was not released as a period piece, but it now functions as such to all who watch it, outclassing Mrs. Miniver in this regard.

While the film pales in comparison to It’s a Wonderful Life in terms of pop culture influence, it does see occasional references. The film is referenced in The Way We Were (1973). It provided episode titles for TV’s 21 Jump Street and Family Matters. Russell’s hooks inspired the intimacy complications between Johnny Depp and Wynona Rider in Edward Scissorhands (1990). And most recently, Tropic Thunder (2008) spoofed Russell’s character with Nick Nolte’s character “Four Leaf Tayback.” (E)

The film was also remade as the TV movie Returning Home (1975), starring Tom Selleck as the Dana Andrews character. Wyler deplored it, saying, “I don’t know why they simply didn’t show the old picture.” (C) Indeed, you could slap The Best Years of Our Lives on screen today and still generate the same passionate political and cinematic debates. But rising above the chatter is a shared tender experience that, to quote The Hollywood Reporter, is “filled with emotional dynamite.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: DVD Booklet

CITE B: The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History

CITE C: George Stevens Jr., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age

CITE D: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE E: IMDB Movie Connections

CITE F: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE G: Richard Flood. “Reel crank – critic Manny Farber.” Artforum, Volume 37, Issue 1, September 1998. ISSN 0004-3532.

CITE H: allmovie.com

CITE I: Tim Dirks, AMC Filmsite.org