Director: Billy Wilder

Producer: Joseph Sistrom (Paramount)

Writers: Billy Wilder & Raymond Chandler (script), James M. Cain (novel)

Photography: John F. Seitz

Music: Miklos Rozsa

Cast: Fred MacMurray, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson, Porter Hall, Jean Heather, Tom Powers, Byron Barr, Richard Gaines, Fortunio Bonanova, John Philliber

![]()

Introduction

“I killed him for money and for a woman. I didn’t get the money, and I didn’t get the woman.”

Never has a line better summed up its genre than Fred MacMurray’s classic film noir confession in Double Indemnity. The money is a $100,000 equity on an accident insurance policy. The woman is Barbara Stanwyck’s beautifully rotten Phyllis Dietrichson, the best example of a femme fatale that’s ever hit the screen.

Together, these elements of greed and lust fuel a complex murder scheme that fulfills the film’s fatalistic promise: “It’s a one-way trip and the last stop is the cemetery.” Film historian Eddie Muller put it best, “If I had one movie to explain to people what noir is, it’s Double Indemnity.”

![]()

Plot Summary

The title comes from the details of the murder plot, a rare “double indemnity” clause that awards extra money to the beneficiary should the insurance holder suffer a fatal accident under rare circumstances. In this case, the holder is Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers), a chauvinistic husband who has no idea his second wife Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) wants to kill him. If executed properly, she could get $50,000 in insurance money, or twice that amount should he die in an extremely rare manner (i.e. falling from a moving train).

This is the danger awaiting insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) when he arrives at the doorstep of the Dietrichson estate in sunny Los Angeles. For Neff, it’s just another stop in his door-to-door sales trip, until he sees Ms. Dietrichson standing atop her staircase, wearing nothing but a towel and a sexy anklet. They immediately hit it off, burning with the desire of forbidden romance.

Before long, they devise a scheme to knock off Mr. Dietrichson and run off together, carefully concocting what they think is the perfect crime, as Walter knows the ins and outs of the insurance world, while Phyllis knows the ins and outs of her husband. But their clever scheme faces three main hurdles: Phyllis’ sweet step-daughter Lola (Jean Heather), her jealous boyfriend Nino Zachetti (Byron Barr) and Walter’s claims manager Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), who’s got a “heart as big as a house” and a “Little Man” intuition that suspects something is awry.

![]()

Writing Trifecta

Voted the WGA’s #26 Greatest Script of All Time, Double Indemnity was a collaboration between three of history’s sharpest writers. First, we have the author of the source novel, James M. Cain, the brainchild behind subsequent adaptations like Mildred Pierce (1945) and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). It was Double Indemnity that proved Cain’s novels could become noir successes on the big screen, contributing a complex murder plot where one of the plotters tries to beat his insurance company at its own game.

The second crucial cog was the incomparable Billy Wilder, one of greatest writer/directors in movie history. Like Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (1941), Wilder reinvented the notion of fractured narrative, starting the script with the chronological end of the story, as Neff recounts the plot events into a recorder in a recurring framing device that’s intercut with flashbacks via voice-over narration. Note how each time we return to this framing device, the blood stain on Walter’s shoulder grows wider.

The third and perhaps most important script contributor was legendary pulp detective novelist Raymond Chandler, who had a knack for sprinkling sharp one-liners into his novels: “It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window.” In 1944, Chandler made the leap from literature to Hollywood, as a pair of his Philip Marlowe detective novels were adapted to the screen. His 1940 novel Farewell, My Lovely became the noir film Murder My Sweet (1944, while his 1939 novel The Big Sleep became a film of the same name with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

In Double Indemnity, Chandler is on the other side of the equation, adapting someone else’s novel. And if there’s a razor-sharp quip in the film, it probably owes credit to Chandler. Some of the hardboiled lines definitely carry a little cheese (like Walter’s constant use of the word “baby”), but that was noir, baby. With words as smooth as his match-lighting technique, Walter Neff fires double entendres about “coverage” (the insurance kind and the towel kind) and how he hates talking with the staircase between them (or anything else between them, including clothes). Sexual references had to be made as discretely as possible in 1944, most famously an automobile metaphor when Dietrichson reveals her first name and Neff decides he’ll “have to drive it around the block a couple times.” When Neff hints that he would like to see her again, Phyllis returns serve with the same vehicle analogy:

Phyllis: There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff, 45 miles an hour.

Neff: How fast was I going, Officer?

Phyllis: I’d say around 90.

Neff: Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket?

Phyllis: Suppose I let you off with a warning this time?

Neff: Suppose it doesn’t take?

Phyllis: Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles?

Neff: Suppose I bust out crying and put my head on your shoulder?

Phyllis: Suppose you try putting it on my husband’s shoulder?

Neff: That tears it…

Having lost this duel of false confidence, Neff leaves the house entirely smitten, as MacMurray’s voice-over narration asks, “How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” In just a few short moments, Double Indemnity has showcased screenwriting that puts other scripts to shame.

![]()

Casting Trifecta

Of course, all the snazzy dialogue would mean nothing if Wilder didn’t case the proper actors to pull it off. In this regard, Edward. G. Robinson steals the show, rattling off entire monologues in long single-takes that prove his knack for memorizing complex dialogue. Just watch this little fire pistol go to work!

Robinson no doubt steals the show, ironic considering he was reluctant to play a supporting part. At the time, he was a major leading man, after the success of his Rico gangster in Little Caesar (1930). But Wilder convinced him to play the part, beginning a successful string of supporting roles from Key Largo (1948) to The Ten Commandments (1956). His Barton Keyes is aptly named, as his relationship with Walter is the key to the film. He is the film’s conscience, and we feel his heartbreak at having been deceived by his best friend, a bond symbolized by lighting a match with the snap of a finger:

WALTER NEFF: You know why you couldn’t figure this one, Keyes? I’ll tell ya. ‘Cause the guy you were looking for was too close. Right across the desk from you.

BARTON KEYES: Closer than that, Walter.

WALTER NEFF: I love you, too.

The other half of that equation is Fred MacMurray, who’s so likeable that he carries our sympathies despite some very immoral decisions (adultery, murder, insurance fraud). Modern viewers will be surprised to see such dastardly deeds done by the man they know as the father figure in TV’s My Three Sons (1960) or the Disney favorite in The Shaggy Dog (1959) and The Absent-Minded Professor (1961). In today’s terms, it would be like Bob Saget plotting a murder with Angelina Jolie. This is a darker side to MacMurray, brought out again by Wilder as the philandering husband to Shirley MacLaine’s mistress in The Apartment (1960). But he was never better than here in Double Indemnity.

Why would Wilder choose a killer for his protagonist? Better yet, why would his protagonist commit more murders in the film than the antagonist? It’s because Double Indemnity is quintessential noir, where nobody is all good or all evil. There’s a certain moral ambiguity in the air, hanging almost as thick as the dust in the Dietrichson living room. It’s an atmosphere where even the innocent ones can be corrupted by the femme fatales of the world — all it takes is a little false confidence. As scholar Thomas Shatz writes, “The generic character is psychologically static — he or she is the physical embodiment of an attitude, a style, a world view, of a predetermined and essentially unchanging cultural posture.” (A)

While MacMurray carries the narration and Robinson steals the show, the film’s most legendary performance comes from the one and only Barbara Stanwyck. It was the part she was born to play, having starred with MacMurray previously in Remember the Night (1940) and having played a two-faced woman before alongside Henry Fonda in Preston Sturges’ comedy The Lady Eve (1941). Stanwyck generated plenty of steam by playing with Fonda’s hair, but she outdoes herself here, staring lustful daggers at MacMurray, smoking post-sex cigarettes on the couch and exiting his apartment, leaving the corner of the rug bent underneath as a clue to their lovemaking. This is so much hotter than any explicit sex scene.

Stanwyck was, of course, a natural brunette, but her cheap blond wig is perfect for the phony Phyllis. Her patient manipulation epitomizes the femme fatale, paving the way for Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce (1945) and Jane Greer in Out of the Past (1947). Few actress deliver better “walk-off home runs” as Stanwyck in the grocery aisle, removing her sunglasses as she says with chilling eyes, “Nobody’s pulling out. We went into this together, and we’re coming out together. It’s straight down the line for both of us. Remember?” No doubt, David O. Russell had this scene in mind when he scripted Amy Adams’ walk-off line to Christian Bale in American Hustle (2013): “Maybe I like him. Maybe I like him a lot. From the feet up, right? Baby.”

![]()

Noir Lighting & Directing

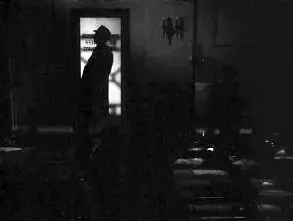

While the hardboiled male and femme fatale are archetypal noir characters, the film’s visual design is also distinctly noir. Wilder routinely allows Walter’s shadow to precede him, the visual version of his dead-man-walking monologue about not being able to hear his own footsteps. Note how Walter appears in silhouette during the opening scene at the insurance office.

Later, during the climax, note how Walter’s shadow precedes him into Phyllis’ house.

Viewers should not be surprised that Walter is a dead man walking in the above shots. Wilder foreshadows it the very minute he enters the Dietrichson house. Oscar-nominated cinematographer John Seitz actually filled the air with aluminum filings to create the illusion of dust and to better reflect the light coming through the venetian blinds. The result is a series of diagonal light beams, enveloping Neff like jail bars.

These venetian blind jail bars return later in a scene with Keyes. You’ll note how Walter is the one painted with the stripes of a prison uniform, while Keyes is not.

Director Billy Wilder possesses that rare ability of visually expressing his characters’ emotional relationships. Note how Phyllis looks down on Walter from the staircase when they first meet, as Walter views her on a proverbial pedestal. Watch how Stanwyck moves forward just enough that the swirling pattern of the railing highlights her crotch. And note how the railing swirls match the curls of her phony blond wig, sucking the protagonist in like the swirling hairdo of Kim Novak in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

These same swirls transfix Walter as he watches Phyllis descend the staircase. His eyes become transfixed on her anklet, which becomes a key familiar image.

Once down the stairs, we get another classic noir icon — the mirror double. As Phyllis looks in the mirror, she says, “I hope I got my face on straight,” foreshadowing her own two-face deception. A similar technique is used in Vertigo (1958), when Kim Novak looks into a mirror and says, “I’ve got my face on.”

This foreshadowing is fully realized during the climax, as Wilder cuts to an omniscient high-angle. This is the only time we break Walter’s first-person flashbacks, as we now look down from above as if fate watching. The 19-second shot holds while Phyllis descends the stairs, unlocks the door and turns off the lights. She proceeds into the living room, places a gun underneath the sofa cushion and sits on it, recalling Walter’s earlier line about “sitting on a hot poker.”

Once Walter arrives, Wilder makes brilliant use of slow disclosure, slowly revealing things that lie in waiting off screen. As Walter closes the windows, he turns to see what we already knew was out of the frame — Phyllis holding the gun. Shortly after, he flips it, as Phyllis decides she can’t kill Walter and pulls him in close. Fittingly, the gun remains off screen, and as Phyllis stiffens up with fear in her eyes, we know Walter has pressed the gun up against her belly. We don’t have to see it. We know it.

Wilder uses a similar “out of the frame” technique during the death of Mr. Dietrichson. Wilder camera holds on Phyllis’ evil eyes as she honks the horn, while Walter strangles Mr. Dietrichson off screen. Sometimes it’s more powerful not to show it.

Other times, it can be enormously suspenseful to show what’s “off screen” to certain characters, but which is “on screen” to we the viewers. Take the scene where Phyllis hides behind Walter’s open door, as Walter speaks to Keyes in the hallway. Keyes does not know how close he is to catching her, but we do. It’s a similar construct as Grace Kelly’s apartment break-in in Rear Window (1954) or Tippi Hedren’s safe heist in Marnie (1964) where we can see someone coming dangerously close to catching them, but they cannot.

Finally, Wilder feels most Hitchcockian during his tracking shot following Walter down the center of the train car, mirroring the opening credits. This increases the tension as we the audience worry he will be spotted, only for Wilder to reveal a man on the back of the train, eagerly waiting to talk to Walter.

![]()

Score

The slow train walk on crutches obviously echoes the opening credits. And what would the opening credits be without the brooding score by Miklos Rozsa?

The score earned him his sixth of 17 total Oscar nominations, of which he would win three for Spellbound (1945), A Double Life (1947) and Ben-Hur (1959). Still, his score for Double Indemnity is my personal favorite, not simply because it is ominous. Listen how it also turns mysterious at the 1:50 mark. Then, allow yourself to be swept away by the beautiful strings at the 2:10 mark. As the piece continues, it returns to the ominous tone with a thundering conclusion.

![]()

Legacy

The film was highly acclaimed upon its release, earning seven Oscar nomination, including Best Picture. While it went home empty-handed, you could argue that it was directly responsible for Wilder winning Best Picture the following year with The Lost Weekend (1945).

Over the years, its pop culture impact grew and grew. The plot was revived for the very good Body Heat (1981), staring William Hurt and Kathleen Turner. It’s hard to imagine other adult thrillers, from Fatal Attraction (1987) to Disclosure (1994) to Unfaithful (2002), without this one. And the notion of a fine-print murder clause was later influential on Double Jeopardy (1999). But it’s not just adult tales of affairs that reference it. The kid character Mike TV mentions the film in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971).

Double Indemnity will remain on movie best lists as long as they are written. It ranked No. 38 on the AFI’s original Top 100 in 1997, and then jumped up to No. 29 when the list was revised in 2007. It holds a key place in film history on a number of fronts. As suspense, it’s nail-biting. As romance, it’s passionately intense. And as noir, it’s as good as it gets. The Maltese Falcon (1941) may have begun film noir, but it was 1944 that gave us Edward Dmytryk’s Murder My Sweet, Otto Preminger’s Laura and Wilder’s Double Indemnity masterpiece. Which brings us back to Muller’s statement: “If I had one movie to explain to people what noir is, it’s Double Indemnity.” Muller insists that noir is Hollywood’s only organic artistic movement. And if that’s the case, what does that say about this amazing film, the epitome of Hollywood’s only organic artistic movement?

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Braudy & Cohen, p. 696, Film Theory and Criticism