Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writer: John Michael Hayes (screenplay), Cornell Woolrich (story)

Producer: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, Patron)

Photography: Robert Burks

Music: Franz Waxman

Cast: James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr, Wendell Corey, Judith Evelyn, Ross Bagdasarian, Georgine Darcy, Sara Berner, Frank Cady, Jesslyn Fax, Rand Harper, Irene Winston, Havis Davenport

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Screenplay

- Signature Cast

- Neighborly Manifestations

- Romantic Subtext

- The Master’s Metaphorical Frame

- Voyeurism & The Male Gaze

- Transitional Spaces

- Diagetic Sound

- Pop Culture Frenzy

- Modern Mainstream Snares

- Legacy

By the late ’40s, Alfred Hitchcock had made roughly 40 films, and like many great artists, he had become restless in his work. Yearning to stretch the boundaries of a medium he had so clearly mastered, he began what some would call his “experimental phase,” a creative flourish that produced Rope (1948), a film shot in ten long “single takes” to create the illusion of one continuous shot; Dial M for Murder (1954), which dabbled in a 3D technology that allowed Grace Kelly to lift a pair of scissors off the screen; even The Man Who Knew Too Much (1955), where he inserted the Doris Day musical number “Que Sera, Sera.”

The greatest in this experimental period was, of course, Rear Window. Here, Hitchcock concocted his most original, most challenging concept yet: to create an entire film from one vantage point, the rear window of a Greenwich Village apartment, and in turn, symbolize the very movie-watching experience and director-viewer relationship that made him a legend.

You won’t find a movie that carries as much surface level suspense, underlying character subtext, and self-reflexive directorial vision than Rear Window. And while there are many movies about movies, none symbolize the medium better than the “movie” Stewart watches — and cuts together with his own eyes — out his own rear window.

“Rear Window is sort of Hitchcock’s testament film,” critic/director Peter Bagdonovich said. “It’s a French term, meaning that in Rear Window, perhaps you see the best example of what Hitchcock’s cinema at its best stood for.” (H)

Plot Summary

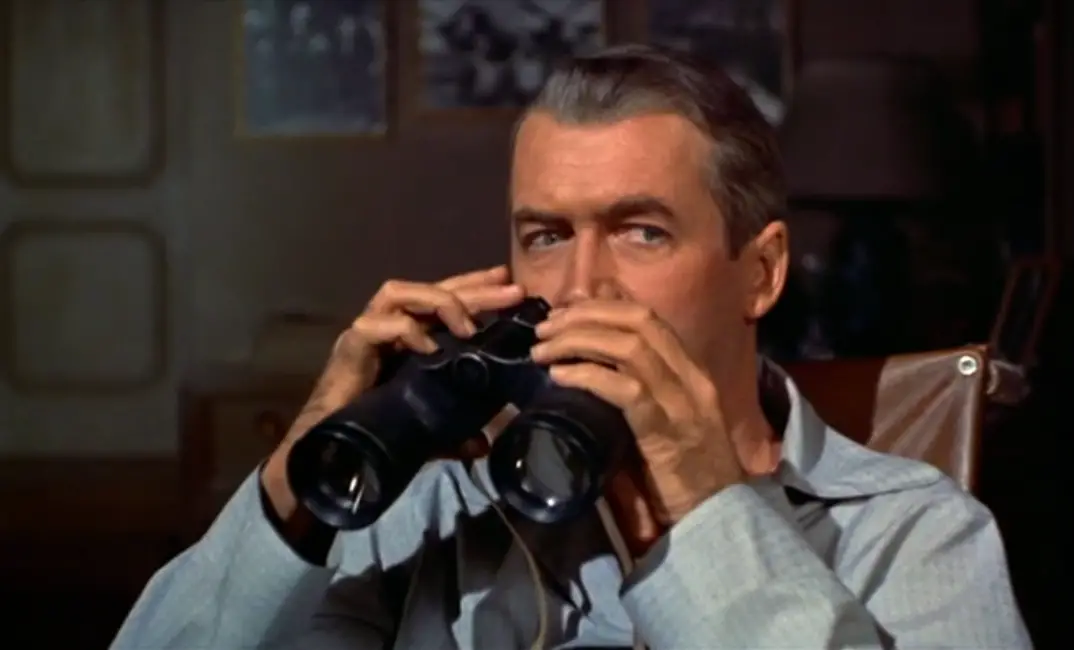

The film’s vantage point is the one held by L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart), a traveling photojournalist, who loves living out of a suitcase and seeing the world. In other words, he lives the life that Stewart’s George Bailey wanted but could never have in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). For such an on-the-go guy, his current condition is particularly frustrating. While photographing a recent auto race, Jeff was apparently hit by one of the cars and broke his leg. Now he’s resigned to sitting in a wheelchair all day in a leg cast, with nothing to do but stare out the rear window of his apartment and “people watch.” The binoculars and long telephoto lenses he has lying around from his profession come in pretty handy.

Of his many neighbors, Jeff becomes most obsessed with Mr. and Mrs. Thorwald, the feuding husband and wife who share a three-window apartment directly across from his. One day, Jeff sees them arguing, and after hearing a loud crash and scream that night, notices the wife is missing the next morning. Jeff continues to watch as Mr. Thorwald (Raymond Burr) behaves suspiciously, rolling up his wife’s bedcovers, wrapping a knife and saw in newspaper and making mysterious late-night trips out of the building carrying his sample case. Is Thorwald simply making night runs as a salesman? Or, has something more heinous actually occured?

Jeff’s fiery old caretaker, Stella (Thelma Ritter), discourages him from getting involved, as does his fashion model girlfriend, Lisa Carol Freemont (Grace Kelly), who wants him to pay her as much attention as he does his voyeuristic whimsies. But as Jeff continues to piece together the puzzle, his case for Mrs. Thorwald’s murder becomes more compelling, and eventually, Lisa and Stella are enveloped in the same curiosity. They become Jeff’s confidants, unlike the cynical detective Lt. Tom Doyle (Wendell Corey), and eventually become Jeff’s legs, going where he can’t to investigate clues in the courtyard below and in Thowarld’s very apartment.

Screenplay

Written by John Michael Hayes from the 1942 short story It Had to Be Murder by Cornell Woolrich, the Oscar-nominated script draws from two real-life incidents. The first, from 1924 Sussex, England, saw Patrick Mahon dismember the body of his mistress and store the pieces in a large trunk, tin cans and hatbox. The second, from 1910 London, saw Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen cut up his wife’s body and run off with his secretary, who was later caught wearing the wife’s jewelry. Hitch knew these stories well and was thrilled to apply them to his own unique blend of suspense and black comedy. (G)

Though he never asked for a writing credit, Hitchcock worked tirelessly on the script with Hayes — their first of four together. You can imagine the giant blocks of text devoted entirely to image and action in that script, as we do more watching here than most any other movie. That’s not to say the dialogue isn’t great, particularly Stella spouting such lines as, “When a man and a woman see each other and like each other, they oughta come together, wham, like a couple of taxis on Broadway.”

The WGA recently voted Rear Window one of the 101 Greatest Scripts of All Time, and to this day it remains a textbook example of how to unravel a mystery. While Jeff is ultimately right about most of his suspicions, the script keeps us enthralled with the desire to prove him right.

A Signature Cast

For Stewart, Jeff is the type of complex role any actor would kill to play: lovable yet fetishistic, full of curiosity and blind to his own saving “Grace.” The role marked a change for Stewart as the moment he shed his “aw shucks” reputation and embraced a darker intensity that was already showing up in such westerns as Winchester 73 (1950), The Naked Spur (1953) and The Far Country (1954). How better to mine the depths of darkness than with Hitchcock?

Rear Window was Stewart’s second of four collaborations with Hitch, after Rope (1948) and before both The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Vertigo (1958). Still, Stewart always considered Rear Window his favorite. When I see him remove his shirt to reveal a scrawny yet flabby body, I smirk thinking about a time when movie heroes didn’t have to be jacked up. And maybe it was better that way. It meant they had to act. Jeff doesn’t need big guns. We watch him because he is a compelling character, period. More actors today should work on chiseling their characters as much as their bodies.

As for Grace Kelly, she is both divine to look at and pivotal in her performance. From the moment Hitch introduces her in that slow-motion, soft-focus kiss, we can’t stop looking at her — much in the way Jeff does the minute she shows an adventurous side. While Hitchcock felt she needed to look a little more “bosomy,” Kelly stayed true to herself, refused to wear “falsies” and altered her posture with a few wardrobe modifications by the indelible Edith Head. (A) No one rocked an Edith Head costume better than Kelly. Sexy doesn’t even begin to describe it; neither does decadent. If you haven’t had a lesson in the class of Princess Grace, Rear Window is all you need.

The film came at the height of her glamour. When she received her Oscar for The Country Girl (1954), it might as well have been a nod to her two collaborations with Hitchcock that year, Dial M for Murder and Rear Window. The following year she would return with Hitchcock in To Catch a Thief (1955), carousing with Cary Grant along the French Riviera and falling for Prince Rainier of Monocco in the process. In a year, she would bow out of acting altogether, offering High Society (1956) as a swan song before marrying Rainer to become Princess Grace. Hitchcock almost pulled her out of retirement for Marnie (1964), but she ultimately declined. Her legend only grew after a fatal car accident in 1982, where she was killed on roads not so far from those she drove in To Catch a Thief. (A)

As for the rest of the cast, Ritter is at her career best, four years after her hilarious quips in All About Eve (1950) and one year after her memorable record-player death in Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953). Ritter may very well be my favorite “character actress” of all time. Watch and you’ll see what I mean. She’s the definition of comic relief.

Corey is solid as Lt. Doyle, the realist counterpoint to Jeff’s suspicions. Did you know that from 1961-1963, he would serve as President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences? Yes, that means he was there when Hitchcock was not even nominated for Best Director for his masterful job on Psycho. Then again, Doyle was always a skeptic.

Finally, Raymond Burr is a nasty Mr. Thorwald, shortly before his stardom as TV’s Perry Mason (1957). Unlike the show, Burr is mostly silent for the duration of the film. It’s rumored Hitchcock chose him because he looked like his former producer, David O. Selznick (Rebecca), whom Hitchcock thought meddled too much in his work. (B)

Neighborly Manifestations

Still, the real stars are the supporting cast of characters that inhabit the Greenwich Village set. We spend just as much time watching these neighbors as we do Stewart, Kelly and Ritter, and we become just as invested in their problems — mostly because we’re jealous of their gorgeous living quarters.

The multi-story tenement, set against that orange New York City sky, is a sight to behold. At the time, it was the largest indoor set ever built at Paramount, measuring 98 feet wide, 185 feet long and 40 feet high. Seeing as Stewart’s second-story apartment was actually at ground level, the courtyard required excavation. (B) In total, there were 32 apartments, 12 of which were fully furnished. (F) Joshua Klein writes that “watching it is like watching a living, breathing ecosystem.” (C) Check out this cool timelapse video of the courtyard:

This “living, breathing ecosystem” is more than just a marvel of Hollywood set design. As Jeff spies on his neighbors to break this so-called boredom, we soon learn his spying is not only a perverted pleasure, but also his subconscious way of weighing his marriage decision. Each neighbor is not a random supporting character, but a carefully-chosen representation of a possible future for Jeff.

There’s Miss Torso, the hot, flexible ballet dancer, representing the ultimate single life and the object of Jeff’s fantasies. Notice the birds on her roof, foreshadowing the “bird = lady” symbolism that Hitch would later use with taxidermy in Psycho (1960) and flocks of killer peckers in The Birds (1963).

There’s Miss Lonelyheart, conversely representing the disaster of single life.

There’s a sculptor and songwriter, both representing the starving artist Jeff might become should he continue his photography. It’s no coincidence that the woman’s sculpture is called “Hunger,” a figure of a man with a giant hole in his stomach.

There’s a newlywed couple with the shade constantly drawn, representing the passionate lure of tying the knot and consummating the marriage.

There’s an elderly couple who sleeps together out on the fire escape and owns a pet dog, representing the happy family life.

Finally, there’s the Thorwalds, representing Jeff’s biggest fear of marital entrapment, a “nagging wife” that pushes her husband over the edge. This is what Jeff sees when he looks out the window. They aren’t merely people; they’re personifications of his own fears and desires.

Romantic Subtext

In this way, Hitchcock becomes more than just a master of suspense. He demonstrates that he is highly aware of his film’s romantic core. While most plot summaries claim this is a movie about a man who claims to have seen a murder out his window, it’s really about that man’s relationship with his girlfriend. Despite Stella’s assertion that Lisa is the perfect woman for any sensible man, Jeff cannot seem to appreciate what he has right in front of him: a beautiful woman who wants to marry him.

While Lisa offers to adapt to Jeff’s adventurous lifestlye, Jeff shoots back with cynical remarks. “Can’t we just keep things status quo?” he asks, revealing himself as the classic complacent Hitchcock lead, one who mistakenly thinks he’s in control of his life and, like Young Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt (1943), begs for something to come along and break his “swamp of boredom.”

This is never more present than in the first scene between Jeff and Lisa. While Lisa enthusiastically discusses her day, watch the way Jeff swishes wine around in his mouth, keeps his eyes low to the ground and the musters only fake smiles (it’s almost comical the way he says, “Ooh, Italian! Italian!”). It’s not the conversation of a man truly interested; it’s one of a man wishing he were someplace else, out of his cast and touring the world again. This idealized life of adventure, and the cause of his distraction from Lisa, is symbolized by Hitchcock’s placement of the sexy Miss Torso in the background while Lisa discusses her day. Note how Jeff can’t take his eyes off her.

As soon as Lisa shifts focus to asking Jeff to settle down with her — “Isn’t it time you came home?” — one can bet Hitchcock will symbolically follow, moving the camera so that the newlyweds’ window is now in the background to symbolize the idea of marriage.

This is mise-en-scene at its finest, and Jeff, of course, dismisses the idea as “nonsense.” As Lisa prepares dinner in the kitchen, Jeff returns his gaze out the window, focusing on Miss Lonelyheart, whom he toasts with his wine glass. The irony is striking — a real, loving woman is right there in his apartment, yet he’s toasting his glass to another woman, a reminder that if Jeff keeps this up, he may just become a Mr. Lonelyheart.

Moments later, the two focus on a song being written by the pianist, which they can hear from across the way. “It’s almost as if it were being written especially for us,” Lisa says, to which Jeff shoots back, “No wonder he’s having so much trouble with it.” Enter one of Hitchcock’s favorite cuts, going from a two-shot of the man and woman together, to a shot of just the woman, like those of Alicia in Notorious or of Midge in Vertigo.

Such a cut brings us inside the woman’s world, showing the extreme emotion of the female, which goes unnoticed by the male. To Jeff, these cocky jabs are merely done for his own psychological release, to make light of a situation that terrifies him. But with such striking reaction shots, Hitch garners sympathy for the woman.

This relationship between Jeff and Lisa is what elevates Rear Window beyond so many other thrillers. Most filmmakers would have been so thrilled to have merely come up with this murder mystery premise that they would have stopped there. Hitchcock, however, worked carefully with screenwriter Hayes to develop the subplot of the relationship. This marriage subplot intertwines brilliantly with the surface mystery plot in a single POV shot of Lisa wearing Jeff’s wedding ring.

Note how Jeff changes his expression after Lisa risks her life in Thorwald’s apartment. It’s not until she enters into his fantasy world — this “movie” he’s watching — that his impression of her begins to change.

The Master’s Metaphorical Frame

In addition to the romantic core, the elaborate set allows for Hitchcock’s most genius thematic creation — using the frame of the rear window as the frame of a metaphorical movie screen. As Jeff watches this “screen,” he decides which neighbors to watch. In doing so, he acts as a director would, cutting from one image to the next. Taking the idea even further, each neighbor’s apartment window serves as the frame of an additional movie screen within Jeff’s rear window frame, which is inside Hitchcock’s overall movie frame. In other words, we get a bunch of movies within a movie within a movie, most of them silent, unfolding as pure visual cinema.

Hitchcock wastes no time in introducing us to this brilliant concept, showing us this rear window frame during the opening credits. Then, in personifed camera (the camera acting like an independent set of eyes), we move out through the window to survey the courtyard and ultimately return back inside the window where we started.

Like the most talented directors, Hitchcock squeezes in all the necessary background info without dialogue, simply showing us various images in the apartment — a thermometer at 94 degrees, explaining why everyone has their windows open; Jeff with sweat beeds on his head and his leg in a cast with his name on it, introducing us to the main character and his wheelchair obstacle; a photograph of an auto-race crash, explaining how Jeff broke his leg; more action photos, explaining Jeff’s job as a traveling photojournalist; and the most important image of all: the beautiful Lisa on the cover of a fashion magazine, introducing the status of his lovely girlfriend, yet an image we first see in “negative,” which is how Jeff first views her.

Voyeurism & The Male Gaze

With all the necessary pieces set up, Hitch is then free to explore his favorite theme of all — voyeurism. Rear Window is the first in a sort of “voyeurism trilogy” for Hitchcock, followed by Vertigo, where an undercover Stewart follows Kim Novak around San Francisco, and Psycho (1960), where Anthony Perkins watches Janet Leigh get undressed through a motel peephole. Rear Window is by far the most blatant of these, as Jeff’s phallic photographic lens serves as what Stella calls a “portable keyhole” and watching serves as the film’s central tenant.

“You can have a man look, you can have him see something, you can have him react to it,” Hitchcock explained. “You can make him react in various ways. You can make him look at one thing, look at another. Without him speaking, you can show his mind at work.” (G)

As the camera gazes out the window, it’s at once Hitchcock’s admission of his own voyeuristic obsession and the ultimate test case in Laura Mulvey’s feminist theory of the “male gaze.” Mulvey asserts that both Vertigo and Rear Window “cut to the measure of the male desire,” where the male gaze “is central to the plot, oscillating between voyeruism and fetishistic fascination.” (D) She notes that Lisa is of little interest to Jeff until she crosses over from the real world and into the “movie” playing out in Jeff’s rear window, at which point “their relationship is re-born erotically.” To Mulvey, Lisa is “a passive image of visual perfection,” introduced in her slow-motion intro and solidified in her obsession with dress and style. (D)

While I agree with much of Mulvey’s theory, I have to side with Tania Modleski’s understanding of Lisa in the article The Master’s Dollhouse: Rear Window. Modleski argues against Mulvey’s claim of a “passive” Lisa, noting that Lisa is far from helpless. It is actually she who takes action and risks the most by entering Thorwald’s apartment. Modleski also points out that Lisa visually dominates Jeff for much of the film, because she stands over his wheelchair. In the very last shot, when Jeff is asleep, it is Lisa who gets the final “gaze” — watching Jeff from behind her magazine of choice — as the song lyric “Lisa” closes the film.

“This is, after all, the conclusion of a movie that all critics agree is about the power the man attempts to wield through exercising the gaze. We are left with the suspicion (a preview, perhaps, of coming attractions) that while men sleep and dream their dreams of omnipotence over a safely-reduced world, women are not where they appear to be, locked into male ‘views’ of them, imprisoned in their master’s dollhouse.” (E)

Still, Modleski agrees with Mulvey’s explanation of Hitchcock’s fetishistic male gaze and calls the placement of Jeff’s hand in the beginning “masterbatory.” (E) This no doubt adds to the sexual frustration of his lower half being bound inside plaster, which mimicks the frustration that, say, viewers experience in a public theater as they’re unable to pleasure themselves while watching Grace Kelly on screen. This is the dirtiness in which Hitchcock deals, but more than being a pervert (which he subconsciously was), his artistic genius allows for a commentary on the matter and thus a hopeful conquering over it.

Is Rear Window not, more than anything, a warning against voyeurism? At one point, Lt. Doyle says, “That’s a secret, private world you’re looking into out there. People do a lot of things in private they couldn’t possibly explain in public.” Stella does Doyle one better, saying, “We’ve become a race of peeping toms. What people ought to do is get outside of their own house and look in for a change.” Jeff seems subconsciously aware of this fact, only it takes him a while to see how it relates to he and Lisa. He poses to himself, “I wonder if it’s ethical to watch a man with binoculars and a long focus lens?”

This becomes both Jeff’s ethical dilemma and our ethical dilemma as viewers, as Rear Window provides an unprecedented, and never since equaled, example of a camera simultaneously acting as our eyes, the director’s eyes and the main character’s eyes. Thus we are forced to see exactly what Jeff sees, and, in moments Jeff sleeps, what Hitchcock wants us to see in personified camera. As we become engrossed in the mystery, we as audiences share Jeff’s desires of wanting this murder to have occurred. We are completely complicit with the death of Mrs. Thorwald out of our own selfish desire for excitement.

Transitional Spaces

“Voyeurism” and the “Male Gaze” are just two staples that let us know this is a Hitchcock movie. Others include his auteur icons of apartment ladders and stairs as transitional spaces between safety and danger. These “icons” were used time and again over his career, from The 39 Steps to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious to Vertigo, Psycho to Frenzy.

Another such Hitchcock icon is the so-called “emerging body shot.” Here, Hitch uses the walls between windows as anxiety-packed hiding places. Characters move from one window to the next, and when they disappear behind walls in the transitional space, we hold our breath to see if they emerge on the other side.

By the time our attention is focused on the tensions of more than one window at once, on more than one floor at once — Lisa searching Thorwald’s apartment, Miss Lonelyheart flirting with suicide, Mr. Thorwald lumbering down the hallway — Hitchcock has us in his grasp. We want to call out, almost in a whisper like Jeff, to stop the danger unfolding before us. But we can’t. For my money, it’s the most heart-pounding moment in movie history. Steven Spielberg agrees: “Nothing beats that for suspense.” (G)

Diagetic Sound

Adding to the feel of watching this “slice of life” is Hitchcock’s use of “diagetic sound,” a fancy term for audio that comes from on-screen sources (i.e. radios, record players, etc.). In fact, the film’s primary theme, “Lisa,” written by Franz Waxman (music) and Harold Rome (lyrics), is supposedly the creation of the film’s songwriter character, a piece he tries to perfect throughout the movie. How genius of a director to have the film’s actual score develop right in front of us as the film progresses!

Two of the film’s best bits of trivia come from this songwriter. Most movie buffs know Hitchcock’s cameo comes in that apartment, fittingly winding a clock, just as he so effectively controls the pacing of the film. What they may not know is that the songwriter character is played by Ross Bagdasarian, better known as David Seville, creator of Alvin & The Chipmunks.

Pop Culture Frenzy

For decades Rear Window was known as one of the “Five Lost Hitchcocks,” joining Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), The Trouble with Harry (1955), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Vertigo (1958) as unavailable due to copyright issues. They were all re-released in theatres around 1984, meaning a full 30 years went by where Rear Window was only seen once, televised by ABC in 1971, though it was not technically legal to do so. (B) Even so, that did not stop other filmmakers from referencing it.

John Carpenter used the name “Doyle” as a specific homage to Lt. Doyle in Halloween (1978). In Michael Antonioni’s British masterpiece Blow-Up (1966), we again see a man trying to solve a mystery via his camera lens. In Brian DePalma’s Sisters (1973) and Body Double (1984), we get murder mysteries sprung from neighborly spying.

In Robert Zemeckis’ What Lies Beneath (2000), the entire opening act has Michelle Pfeiffer suspecting the murder of the neighbor’s wife, even spying on them with a pair of binoculars. Most recently, the Shia LaBeouf film Disturbia (2007) was actually sued for ripping off the Rear Window story.

On television, it seems every sitcom has a devoted an episode to the film. A very famous Simpsons episode featured Bart with a broken leg and suspecting Flanders of killing his wife. That ’70s Show referenced it multiple times. One of the funniest recurring gags in Friends was the gang looking out their rear window at the Ugly Naked Guy. And arguably the greatest episode of Seinfeld, “The Contest,” featured Jerry and Kramer staring at a naked woman in a nearby apartment.

The film was even remade as a 1998 TV movie, featuring a wheelchair-bound Christopher Reeve.

Modern Mainstream Snares

The film’s impact is so widespread that most viewers today don’t even realize they’ve seen the references in their everyday pop culture. And yet, a few elements elicit some reservations from these viewers, namely moments of datedness. Every time I show this film to today’s audiences, I always notice snickers and eye rolling at several parts, including the helicopter at the start of the film, and the dated special effect of Stewart falling out the window during the climax.

Still, most snickers come during Stewart’s flashbulb defense against Thorwald. Did this play better for audiences of the ’50s? Or does Hitchcock simply tease out the suspense too much? Viewers who are bugged by this should remember Jeff’s earlier explanation of a flashbulb “warning signal” and admire his character’s resourcefulness, using the only weapon he has, a camera, to fend off his attacker.

Legacy

Despite these minor durability issues, today’s mainstream viewers are overwhelmingly pleased with Rear Window, voting the film a whopping 8.8 on IMDB, good for #14 on the list. This public seal of approval is echoed by the academics, who vote Rear Window #48 on the AFI Top 100 Films, #14 on AFI’s 100 Thrills and #3 on AFI’s Top 10 Mysteries.

Still, the film was not appreciated in its own time. Rear Window did not earn a single Oscar, and while it earned Hitch his fourth nomination for Best Director, he again went home empty handed, thanks to Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954). With all due respect to Kazan’s masterful directing of actors, his directorial vision in Waterfront does not come close to Hitchcock’s here.

Rear Window really boasts the perfect marriage of all the finest filmmaking elements — a master director’s overarching vision; a smartly written script both in plot and dialogue; emotionally complex characters performed by a brilliant cast; stunning visuals in both Kelly’s wardrobe and the courtyard set piece; music that emanates from the film and progresses toward completion; and a powerful message — that inside your immediate world may lie everything you’ve been looking for on the outside.

Citations

CITE A: David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: IMDB Trivia

CITE C: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE D: Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Film Theory & Criticism

CITE E: Tania Modleski, “The Master’s Dollhouse: Rear Window,” from The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory, Film Theory & Criticism

CITE F: filmsite.org

CITE G: AFI Top 100: 10th Anniversary Edition (CBS)

CITE H: DVD Documentary