Director: Sam Peckinpah

Writers: Walon Green, Roy N. Sickner, Sam Peckinpah (screenplay)

Producers: Phil Feldman, Roy N. Sickner (Warner Bros./Seven Arts)

Photography: Lucien Ballard

Music: Jerry Fielding

Cast: William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, Edmond O’Brien, Warren Oates, Ben Johnson, Jaime Sanchez, Emilio Fernandez, Strother Martin, L.Q. Jones, Albert Dekker, Bo Hopkins, Dub Taylor, Paul Harper, Jorge Russek

![]()

Introduction

When The Wild Bunch arrived in 1969, even the most respected critics were torn over whether Sam Peckinpah had created a masterpiece or an abomination. My very first film mentor, Baltimore Sun critic Michael Sragow, fondly recalled the summer of ’69, when he saw The Wild Bunch six times in two weeks and wrote a piece to his teacher insisting it was the greatest film ever made. Impressed, the teacher helped Sragow get into NYU film school and become the first regular movie critic for Rolling Stone magazine. Thirty six years later, I discovered the film at Sragow’s behest in 2005, and my affection for it has grown exponentially with multiple viewings.

On the one hand, I envy Sragow and others’ ability to experience The Wild Bunch in its full shocking debut, before the world became desensitized to violence. On the other hand, it’s been a privilege to bypass years of controversy over the film’s merits, and view it with the certainty that what I’m witnessing is a masterpiece. How lucky I am not to have seen the Oscar snubbing in 1969.

The Wild Bunch received just two Oscar nominations, for screenplay and score, losing both to Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969) for William Goldman and Burt Bacharach, respectively. While Butch & Sundance was more deserving in both those categories, the egregiousness comes in that it was nominated for Best Director and won Best Cinematography, while The Wild Bunch wasn’t even nominated in either category. What’s more, Butch & Sundance received an “Eddie” nomination by the American Cinema Editors, while The Wild Bunch got nothing for its groundbreaking editing. Anyone who’s seen even the first first 10 minutes, knows that this is a travesty.![]()

Plot Summary

The film opens as a band of aging outlaws, “The Wild Bunch,” led by Pike Bishop (William Holden), rides into the Texas town of Starbuck, disguised as members of the U.S. Calvary. They think it’s the perfect guise to rob a bank, but really, they’re being set-up by bounty hunters, funded by corrupt railroader Harrigan (Albert Dekker) and led by Pike’s ex-partner, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan). A bloody shoot-out ensues, wounding countless innocent bystanders and sending The Wild Bunch on the run with the bounty hunters right on their heels. Deke’s chase is personal, as he wants to avenge a past betrayal by Pike that landed him at Yuma Prison. Yet, somehow, deep down, we feel he wishes he were part of the Bunch, and thus laments chasing a group he admires. Perhaps he just misses the camaraderie.

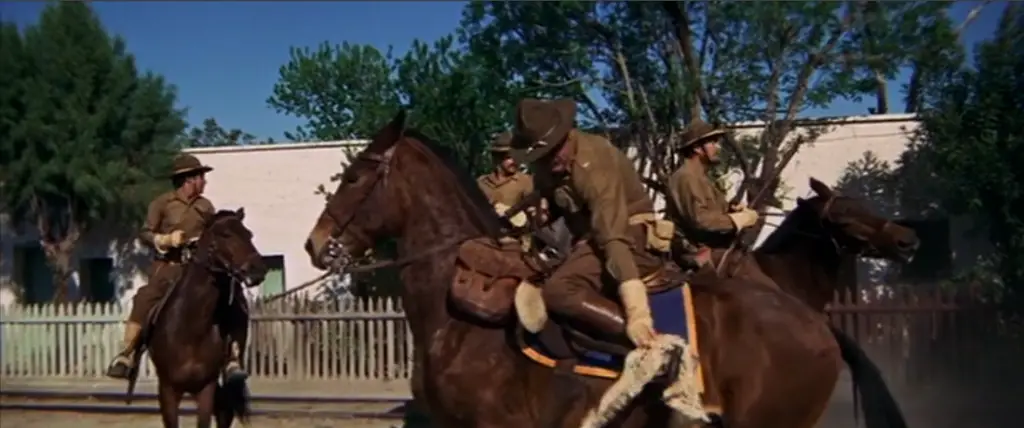

The Wild Bunch — Pike, his sidekick Dutch (Ernest Borgnine), Angel (Jaime Sanchez) and the extra-wild Gorch Brothers (Warren Oates and Ben Johnson) — are a group of macho men playing by their own rules, while sharing laughs, booze and women. The only problem — the year is 1913, and they’ve yet to adapt to 20th century America. As the movie posters say, The Bunch was “born too late for their own times.” (B) Their answer? Delay the inevitable by crossing the border and pulling jobs amidst the Mexican Civil War.

After meeting up with their old friend Sykes (Edmund O’Brien), they go to work for Mexican General Mapache (Emilio Fernandez), described as “a killer for Huerta,” the man who sparked the civil war by overthrowing Mexican President Francisco Madero. (C) Mapache starts as a business partner, employing them in a train robbery for guns, but he quickly becomes their enemy, when he detains and brutalizes Angel over a personal feud. Hunted by Deke and being pissed on by Mapache, The Wild Bunch is left with no other choice than to ride into Mapache’s fortress and ask for Angel back, even if it means they must go out, guns a blazin’ in a battle so violent it’s come to be known as “The Battle of Bloody Porch.”

![]()

Accessing a Complex Script

The story is no doubt epic, with themes so deep and an approach so unique that many first-time viewers may feel lost in the mayhem. I say this because I, too, was lost when I first saw it. Bottom line: I wasn’t ready for it. Now with this review, I hope to soften the “what did I just see” blow for those first approaching The Wild Bunch, while pointing out other things that frequent watchers may have not seen. Realize you may experience a feeling of inaccessibility the first time. But when you come out on the other side, I hope you, too, are a convert.

Your first “in” to the film will be its killer dialogue: “Kiss my sister’s black cat’s ass.” “Here you are with a handful of holes, a thumb up your ass and a big grin to pass the time of day with.” “That general would just as soon kill us as break wind.” “[Your word] is not what matters! It’s who you give it to!” And, of course, “If they move, kill ’em,” voted #72 in Premiere’s 100 Greatest Movie Quotes. Still, the best speech comes from Pike: “When you side with a man, you stay with him, and if you can’t do that, you’re like some animal! You’re finished! We’re finished! All of us! Mount up.”

The Writers Guilds named the script one of the Top 101 Screenplays of All Time. And ironically, for a director so acclaimed as Peckinpah, it was his screenplay that became the only thing ever to earn him an Oscar nomination. Originally written by Walon Green and Roy Sickner, the script was picked up by Warners Bros. and handed to Peckinpah to re-write, with the goal of beating the release of Butch & Sundance by 20th Century Fox. (D) Consider the film’s theme of aging outlaws outside their time, it was a fitting race against the 20th Century (Fox). Only this time, The Wild Bunch won the race.

The choice of handing the reins to Peckinpah was a gamble for Warner Bros. He had been a hot commodity after his first two films, The Deadly Companions (1961) and Ride the High County (1962), but had since become notorious for his clashes with producer Martin Ransohoff, who fired him over a nude scene in The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and fought with him over the flop of Major Dundee (1965). (E) As biographer David Weddle said, Peckinpah “was grasping for something he couldn’t quite do yet.” (A) So after three years scrounging for work and directing TV, he got tapped for a second chance in film. It was The Wild Bunch, and this time, he was ready.

![]()

The Cast

The first order of business was to assemble his cast of aging outlaws. For Deke and Dutch, Peckinpah looked to a pair of actors in their 50s, whose performances he enjoyed in The Dirty Dozen (1967) — ’40s Oscar nominee Ryan (Crossfire) and ’50s Oscar-winner Borgnine (Marty). Johnson and Oates were both holdovers from Major Dundee; Fernandez a famous Mexican film director; and O’Brien a recent Oscar-winner for Seven Days in May (1964). As for the duo of pillaging vultures, Peckinpah cast Strother Martin and L.Q. Jones, who actually requested to play the roles with a hint of homosexuality. (C) The film also marked the last appearance for Dekker, who died months after filming.

Which brings us to the lead of Pike Bishop. Hollywood’s biggest leading men were considered for the role, including Lee Marvin, Burt Lancaster, James Stewart, Charlton Heston, Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. At one point, Marvin had even accepted the role, but pulled out when he was offered more money to appear in Paint Your Wagon (1969). (F) Sometimes the biggest payday doesn’t pay. Rather than Marvin going down as the leading man of this masterpiece, the legacy goes to Holden, who may have been better suited to play the role of aging hero. After all, he was 51 at the time, well past his prime of Sunset Blvd. (1950), Stalag 17 (1953) and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). As Thomson writes, “You could take a dozen or so maturing close-ups of Holden and the series would tell the horrible story of movies as a marinade called early embalming.” (B)

![]()

Out of Time, Out of Place

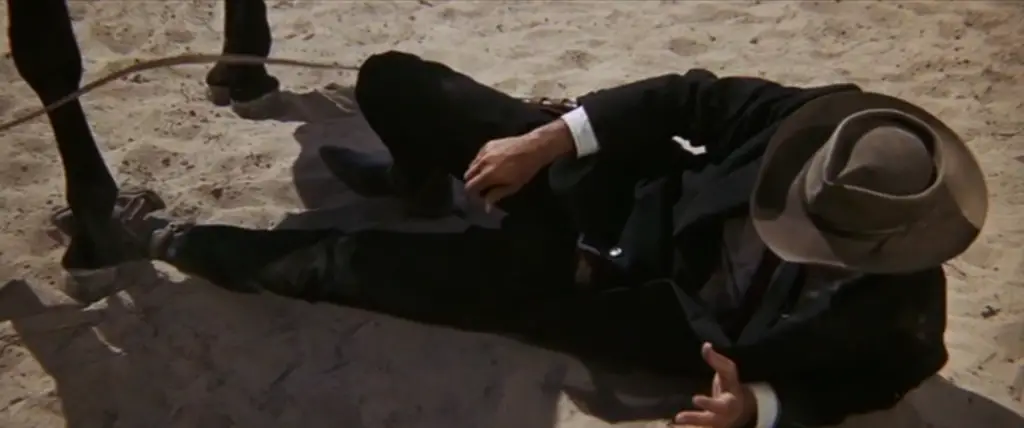

Within a span of 15 years, Holden, Ryan, Dekker and Peckinpah had all died, cementing the film’s theme of dying outlaws. Decades before Eastwood fell off a horse in Unforgiven (1992), it was a unique concept to have Holden fall from his. There’s something so sad about that image of his foot harness snapping, him falling to the ground, hearing his buddies tell him to “cash in his chips and find another game,” and answering them by gritting his teeth, getting back up on the horse and riding into the horizon. Is that not much more powerful than some flawless western hero riding off into the sunset?

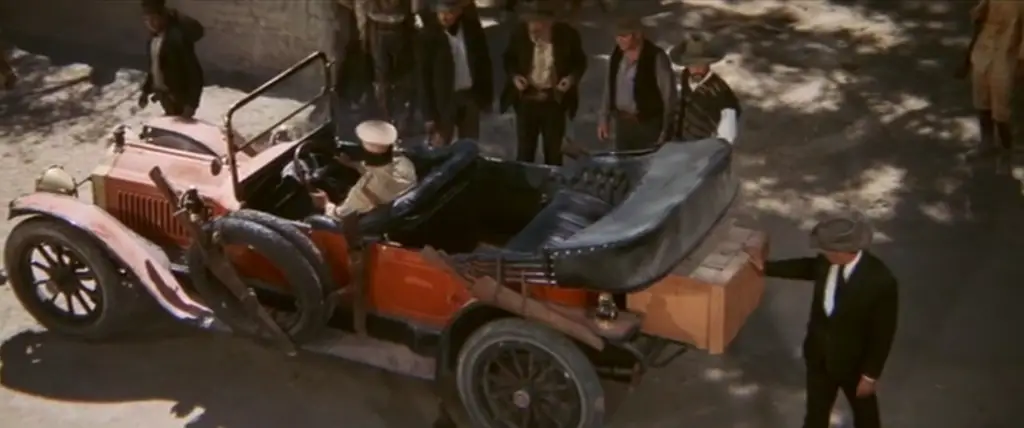

The theme of age is what truly makes The Wild Bunch so fascinating. It’s men wanting to “ride the high country” at a time when the country has become “no country for old men.” Notice their wonder the first time they see a Model-T Ford and their naivety in calling an airplane a “car that flies.” When Pike says, “Let’s go talk to the general about his automobile and our extra horses,” it’s a biting juxtaposition of different kinds of horse power.

If they are impressed by the horsepower of an automobile, they are in absolute awe at the killing power of a Gatling gun. How fitting that they die while trying to harness the power of the machine gun.

Pike knows he is out of place, and even makes gestures to adapt. He says, “What I don’t know about, I sure as hell am gonna learn,” and, “We gotta start thinkin’ beyond our guns. Those days are closin’ fast.” He even considers quitting the outlaw lifestyle. He says, “This was gonna be my last. Ain’t gettin’ around any better. I’d like to make one good score and back off,” to which Dutch replies, “Back off to what?” The film knows its heroes are helpless against the inevitable. And for this, John Wayne, ever the western traditionalist, actually complained the film destroyed the myth of the Old West. (C)

Peckinpah saw it differently, saying, “Those old boys who bring tears to the eyes were real bastards, unchanged men in a changing land.” (G) They truly did bring “tears to the eyes.” During Holden and Borgnine’s campfire scene, when they agree they “wouldn’t have it any other way,” Peckinpah struggled to yell, “Cut!” because he was crying. (C)

This is why it’s so sad when Pike, his face half-lit, walks into the room and solemnly says to his men, “Let’s go.” It’s not just, “Let’s go to fight General Mapache,” it’s “Let’s go from this world. Our time is up.” Immediately after saying this, he looks down and sees a puffed up bird, dying. It’s foreshadowing of what’s to come, as if the group’s long walk to Mapache’s fortress is a funeral procession.

When it’s all done, the men are ready to be picked apart by vultures, as Peckinpah intercuts shots of real vultures with those human “vultures” played by Martin and Jones.

![]()

Violent Vietnam Protest

The generational violence that ultimately destroys them embodies yet another of Peckinpah’s theme — the protest of the Vietnam War that was well underway in 1969. A former Marine in the ’40s, Peckinpah seems to say that the U.S. Army, who was so gallant in World War I and II, was now struggling in Vietnam because it was a new kind of war, where the “old way” no longer worked. America was the Wild Bunch in a new jungle land.

It’s no coincidence that Pike says, “We share very few sentiments with our government” and “There’s a hell of a lot of people that just can’t stand to be wrong … and they can’t forget it, that pride, being wrong, or learn by it!” He is no doubt speaking of those who hold steadfast that it was a good idea to go into Vietnam and insist that the war ended in a tie. The ultimate fulfillment of this statement comes when we see a man hobbling down the street on one leg. Similar images of wounded vets covered the TV every night in ’69.

![]()

Women and Children

What does this violence do to the youth who witness it? This is a major concern of Peckinpah. Most simple is the image of a woman breast-feeding her child with a strand of ammo crossing her chest. More obvious are the cutaways to shots of kids watching the opening attack (one of whom is Peckinpah’s real-life kid), or the group of them that run around mimicking the killers, forming finger guns and shouting, “Bang! Bang!”

The film actually opens with a group of kids giggling as they force a scorpion to be eaten by red ants, which they then set on fire. What is our childish fascination with violence? Why does it exist? And what does it say about us adults, especially when Holden says, “We all dream of being a child again. Even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all?”

By the end, the kids actually factor into the bloody battle. Note that it’s a kid who picks up a gun to avenge General Mapache’s death, highly influential on City of God (2002). How powerful a statement by Peckinpah to have a kid deliver the fatal blow to his main character! And how symbolic to see youth triumph over the wise old veteran, shooting him from behind, like the past finally catching up to him.

We also see kids watching the old men drink whiskey and call women “whores.” It’s Peckinpah’s statement that adults, often accidentally, pass on their backward misogynistic views to future generations. In a way, perhaps Peckinpah becomes guilty of it himself. Women are never safe in The Wild Bunch. During the opening fight, a guy goes flying through a garment store window, knocking over female mannequins, after which we immediately cut to a shot of Crazy Lee (Bo Hopkins) sexually assaulting a woman.

We also see Pike’s horse trample a woman, which he realizes only later once they’ve left town, leaning down to remove a woman’s shawl still stuck to his boot. It’s an image so easy to overlook on first viewing, but on repeat viewings, it’s got the power to make you cry. These are the details strong directors include. (B)

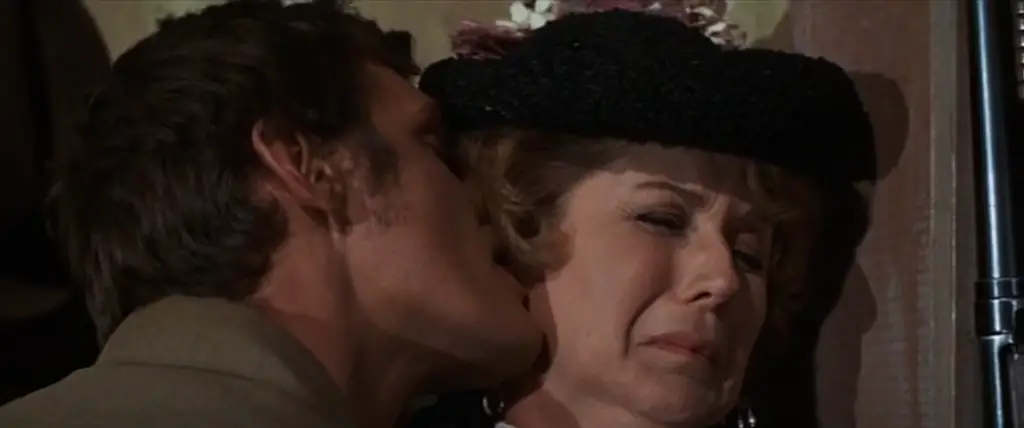

The threat to women continues throughout. It’s the cheating “whore” who pays the price for a beef between Mapache and Angel. During the betrayal flashback between Pike and Deke, it’s the woman who takes the bullets — with breasts exposed, mind you. And during the final battle, not only does Dutch use a woman as a human shield, but Pike yells, “Bitch!” as he shoots a woman for shooting him in the back.

In these guys’ twisted world, it’s acceptable to laugh about doing women in “tandem” and frolicking with a pair of Mexican prostitutes in a wine vat. Ben Johnson claims the two actresses were real prostitutes from a nearby brothel, hired by Peckinpah just so that he could say he got Warner Bros. to pay for hookers in his cast. (C)

The charges of misogyny continued toward Peckinpah, especially after his film Straw Dogs (1971), with the subject of gang rape. (H) But was Peckinpah a misogynist himself, or merely calling out the injustice by depicting it? You could spin it either way. No matter where you fall, you must marvel at the skill and passion in which he raises the issue. As Taxi Driver screenwriter Paul Schrader says, “The power of The Wild Bunch is that Peckinpah says, ‘Look, I know this is anachronism, I know this is fascist, I know this is sexist, I know this is evil and out of date, but God help me, I love it so.” (A)

Why does he love it so? Because the Old West, for all its flaws, is part of the American culture. And after the greats like John Ford, Howard Hawks and Anthony Mann had begun to question it, by the 1960s, Sergio Leone and the Italians had snatched the championship belt from the Americans. In many ways, it was up to Peckinpah to reclaim it. (I) And he did, by creating something the likes of which no one had ever seen.

![]()

Master Director: Bloody Sam’s Bloody Ballet

Peckinpah’s stamp is there from the opening credits, freezing the live shots into chiaroscuro images, while flashing the name of each actor on screen. (B) Sometimes, the freezing even comes as the actors are mid-sentence — a sign of the fracturing to come.

Moments later, we are hit by a barrage of images in the bloody shootout that can only be described as organized chaos. Some have even called it a “bloody ballet,” as the violence unfolds as carefully as an organized dance. The technique most synonymous with The Wild Bunch is Peckinpah’s pioneering use of slow motion. It had been done before, famously in Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (1954) and, more immediately, in Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Peckinpah first learned the concept from editor Lou Lombardo, with whom he had worked on TV’s Noon Wine (1966). It was Lombardo who showed Peckinpah a shooting scene he had edited for TV’s Felony Squad (1966), in which he mixed slow motion with real-time action, after which Peckinpah excitedly said, “Let’s try some of that when we get down to Mexico!” (F)

Try it he did. Peckinpah filmed the major shootouts with six cameras operating at different film rates, including 24, 30, 60, 90 and 120 frames per second. (C) He shot 333,000 feet of film from 1,288 different camera set-ups, requiring him stay in Mexico for six months to help Lombardo edit the thing. (E) The shots arrive at an alarming rate, fired from guns and film cameras. The Wild Bunch set a record for more edits — 3,643 — than any other Technicolor film up to its time. (B) More blank rounds (90,000) were discharged in making the film than there were live rounds fired during the entire Mexican Revolution of 1914. (C) When it was all said and done, about 10,000 squibs (simulated bullet hits) had been used. (C) Seeing The Wild Bunch today, one can’t help but marvel at its influence on Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs), Billy Bob Thornton (Sling Blade), the Wachowskis (The Matrix) and Michael Mann (Heat), who voted the film in his Top 10 of all time.

But it’s not just the number of cuts, squibs, and dead bodies that make the film great. To say that would be to make the mistake of too many superficial fans and filmmakers. The reason The Wild Bunch is so great is how its done, Peckinpah’s ability to harness the madness, to pull quality from the quantity. The orchestrated fracturing of images is mind-boggling. Take for instance, the simple action of a guy being shot off a roof and falling to the ground. We first see him shot and begin to fall, then we cut to four different images before we return to the man in mid-air. After this, we cut to four more images before we cut to him falling again; then cut to three more images before we finally see him land. It’s as if we viewers are frozen in time, waiting for the action to be completed.

Working on a similar principle is Peckinpah’s groundbreaking use of intercutting two distinct actions. We see it once, intercutting the image of a guy getting shot and thrown from his horse, with the image of another guy getting shot from a horse and falling through a garment store window. We see it again later during the train robbery, intercutting two different people falling from the train, where Peckinpah reprises his motif of four edits in between. More broadly and narratively, we see a similar concept applied to the flashbacks of both Pike and Deke, who share the same flashback of a shared experience, but from separate camp fires, as one pursues the other.

The weaving of this tapestry of shots is masterful, but the shots themselves are equally as impressive. Using anamorphic lenses, Peckinpah gives dimension to the sprawling western landscapes. And often, the camera becomes a way of surveying that landscape. At one point, it becomes a pair of binoculars and zooms way in to see figures on horseback, figures that weren’t even visible in the start of the shot.

The zooms are also effective in long-take, where we start on a guy waving his hands atop a ridge, then zoom out until he’s miniature in the distance, pan right to another guy waving his arms on horseback, then zoom in on him as he turns and waves to someone else.

The characters’ sightlines in this vast space take on new importance, as the camera pans, tilts and zooms rapidly to simulate the characters’ frantic, paranoid gaze. We see these rapid “movements” used in association with close-ups, to see the robbers’ faces during the train robbery, or most memorably as the bunch looks at each other in that final quiet moment before all hell breaks loose. It’s Peckinpah’s attempt to outdo Leone, and he may just succeed. The barrage of close-ups on faces recalls Howard Hawks in Red River (1948), and the final montage of the men laughing feels like a mixture of Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948).

Quite literally, the camera is “in-your-face.” There are times we feel that we are actually being thrown from a horse and smashing into the ground, or that we are are tumbling down a dusty hill. Billy Bob Thornton fondly recalls the experience of seeing it: “It was just like you felt the dust was in the theater or in your living room.” (A)

![]()

Controversy

While being immersed in the action of rolling down a hill wasn’t quite so bad for viewers, standing witness to the film’s bloody bookends was too much to handle for many viewers. What too many didn’t get, and don’t get today, is that the slow-motion violence was not meant to glorify it. It’s done to show violence in all its horror, so that Peckinpah can say, “See how damaging and pointless all this violence is?” In Peckinpah’s own words:

“The point of the film is to take this facade of movie violence and open it up, get people involved in it so that they are starting to go in the Hollywood television predictable reaction syndrome, and then twist it so that it’s not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut . . . It’s ugly, brutalizing, and bloody awful; it’s not fun and games and cowboys and Indians. It’s a terrible, ugly thing, and yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement, because we’re all violent people.”

The man nicknamed “Bloody Sam” believed that witnessing the horrors of violence helps us free ourselves of the desire to commit such acts. He later admitted he was wrong, that audiences responded in the opposite way. They were aroused by the violence and reveled in it, something that Peckinpah always regretted. (F) Just how violent is it? Let’s just say that when it was re-submitted to the MPAA in 1993, the film got an “X” rating! This was 24 years after it was made, just five years from the violence of Saving Private Ryan (1998)! Those of you who remember the shock-level the first time you saw Private Ryan, imagine the same thing 30 years prior!

For those who complained of the controversy, Peckinpah always had one answer: “I’m a great believer in catharsis. When people complain about the way I handle violence, what they’re really saying is ‘Please don’t show me; I dont want to know.'” (G) Oates may have best described the adverse reaction: “I don’t think he’s a horrible maniac; it’s just that he injures your innocence, and you get pissed off about it.” (B)

![]()

Legacy

Thankfully, not everyone was pissed. Peckinpah was nominated by the Directors Guild of America. Cinematographer Lucien Ballard was nominated by the National Society of Film Critics. And over the years, the film has been entirely vindicated.

Joss Whedon used at least three names from the film in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997), starring a vampire named Angel, vampire cowboys named Lyle and Tector Gorch, and a Luke Perry character named Pike in the movie version. (C)

Those that first screamed “gratuitous violence” have changed their tune to “bloody ballet,” and most critics today hail the film as a masterful “dirty western.” It’s actually even moved ahead one spot, from #80 to #79, between the AFI’s original Top 100 and its 10th Anniversary revision.

Which brings us full circle to its head-to-head match-up with Butch & Sundance. While The Wild Bunch remains behind Butch & Sundance on the AFI’s Top 100, it places one spot ahead of it on the AFI’s Top 10 Westerns. Peckinpah would likely have taken that distinction, as he was such a fan of the Old West. And in a clever move by him, he carved out his own piece of western history to comment on — turn-of-the-century American along the Texas-Mexico border. If fate draws us each to one time and place to leave our mark, his was there, and his treatment of that area is his ultimate triumph over Butch & Sundance, which sends its heroes to Bolivia for a final shootout that pales in comparison in both build-up and execution.

Is this vindication enough to give Peckinpah’s soul rest? He’s been dead for decades, but the romantic in us wants to believe our work lives on with the power to redeem our life’s transgressions. There’s no doubt Peckinpah had his demons in this world — alcohol and drug addictions to name a few. But work like The Wild Bunch is so brilliant, so cathartic that it redeems. My own analysis is futile compared to that by Peckinpah’s own buddy Kris Kristofferson:

“Sam left behind a wide path of personal and professional wreckage, a legacy of self-indulgence and mayhem, even cruelty, and a handful of the greatest films ever made. He was the master of the loaded moment, whether that moment led to death, triumph, or both. … Sam was a traditionalist and a renegade, a romantic as well as a fatalist. And for most every sin there was a penance, for every betrayal, an act of redemption. He left us a lasting body of original and haunting work, and in the end, Sam Peckinpah [in the words of Ride the High Country] entered his house justified.” (A)

![]()

CITE A: Sam Peckinpah’s West: Legacy of a Hollywood Renegade (DVD Bonus Feature)

CITE B: Tim Dirks, Filmsite.org

CITE C: IMDB Trivia

CITE D: Carroll, E. Jean (March 1982), “Last of the Desperadoes: Dueling with Sam Peckinpah,” Rocky Mountain Magazine

CITE E: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE F: Weddle, David (1994). “If They Move…Kill ‘Em!”. Grove Press. ISBN 0–8021–3776–8.

CITE G: Moritz, Charles. Current Biography Yearbook 1969 with index 1961-1969. The H.W. Wilson Company, NY, 1970. Print.

CITE H: The Film Snob’s Dictionary by David Kamp and Lawrence Levi

CITE I: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die