Director: Frank Capra

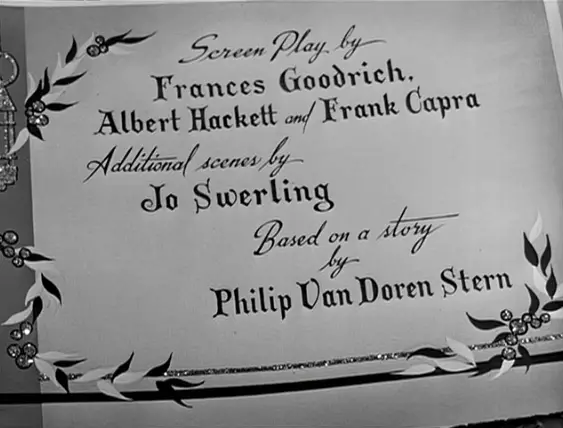

Writers: Philip Van Doren Stern (story), Frances Goodrich, Albert Hackett and Frank Capra (screenplay), Jo Swerling (additional scenes)

Producer: Frank Capra (Liberty Films)

Photography: Joseph Biroc, Joseph Walker

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Cast: Jimmy Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore, Thomas Mitchell, Henry Travers, Beulah Bondi, Frank Faylen,?Ward Bond, Gloria Grahame, H.B. Warner, Frank Albertson, Todd Karns, Samuel S. Hinds, Lillian Randolph, Sara Edwards, William Edmunds, Sheldon Leonard

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- It’s a Wonderful Cast

- Screen Legends: Stewart & Barrymore

- Screenplay: A Christmas Card Carol

- America’s Internal Struggle

- Capra’s Independent Film

- Freeze Frames & Focus Pulls

- Power Reversal

- Mise-en-Scene: Everywhere a Sign

- The Divine Divider

- Happy New Year: In Jail

- Bedford Noir

- Direct Camera Address

- Leaving the Frame

- Single Take: Romance in Real Time

- A Smashing Soundtrack

- Visuals & Effects

- Pop Culture

- It’s a Wonderful Second Life

- Final Thoughts

For a film that’s become such a fixture in our homes each holiday season, it’s amazing how much Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life still has the ability to shock viewers with the same reaction: “I forgot how dark it is. How serious. How little it actually focuses on Christmas.” Indeed, Capra uses the holidays as a mere framing device for an in-depth character study into one man’s life of disappointment — a kind of film noir with a second chance, a human tragedy with revisionist fantasies.

“Happiness here was pursued by the hounds of living hell; the American Dream was so close to the nightmare,” critic David Thomson writes. “The film that had failed in 1947 had become a token of uplifting fellowship, yet it was a film noir full of regret, self-pity and the temptation of suicide. How could so many people convince themselves that it was cheery?”

The answer can only be that Capra shines through the darkness with such blinding truth, pitting dreams of personal greatness against the duties of reality and the common cause. It’s a fable of mankind’s interconnectedness, where each of us is an irremovable cog in a wheel where you can only take that which you have given and where no man is a failure who has friends.

The infamous “Capra-corn” had finally found its proper doses. It’s a Wonderful Life proves we need the darkness to see the light; the lows to feel the highs; the despair to feel the inspiration. Capra needs to beat up George Bailey for two hours before he can save him, just like The Shawshank Redemption (1994) needs to beat up Andy Dufresne before it can free him. It’s no coincidence that Shawshank‘s director called Capra his most influential filmmaker, just like Steven Spielberg says It’s a Wonderful Life is one of three movies — along with A Guy Named Joe (1943) and The Searchers (1956) — that he watches before shooting every film. They had learned from the master.

How fitting that Spielberg ties Capra for the most films (5) on the AFI’s 100 Cheers, a list of history’s most inspirational movies, topped by It’s a Wonderful Life. Spielberg called it “a five hanky movie,” and you’d be hard-pressed to find those who disagree. Few films have touched audiences like this one, from the sappiest of wreath-hangers to the most hardened of cynics. What better tribute than the fact that Capra and Jimmy Stewart always considered It’s a Wonderful Life the best film either of them ever made?

Plot Summary

The film opens on Christmas Eve, 1946, with the citizens of Bedford Falls praying for the life of George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart), a man contemplating suicide after a life of doing everything right only for nothing to go according to plan. The prayers are answered by God in heaven, who sends for George’s guardian angel, Clarence Oddbody (Henry Travers). He promises Clarence a chance to earn his wings if he can convince George that his life is worth living. In order to do so, Clarence must get caught up on George’s life, and we viewers go along for the journey.

We first see George as a young kid (Bobbie Anderson), as he saves his kid brother, Harry, from drowning in a frozen pond. He tops his own act of bravery by stopping his drugstore boss, Mr. Gower (H.B. Warner), from accidentally poisoning kids in a moment of grief. He also stands up for his father, Peter Bailey (Samuel Hinds), against Henry F. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), the “richest and meanest man in the county,” who’s trying to wipe the family business, the Bailey Building and Loan, off the map.

As a young man, George announces dreams of “shaking the dust off this crummy little town and seeing the world.” He never gets around to doing it, as obstacle after obscale keeps him grounded in Bedford Falls: his father’s death, a board decision at the Building & Loan, Harry’s surprise marriage and job offer, an unexpected romance with his childhood friend Mary Hatch (Donna Reed), marriage, a bank run the night of his honeymoon, and fatherhood.

As George builds the quaint Building & Loan into a community favorite, it becomes a thorn in the side of Mr. Potter, who owns half of Bedford Falls and would rather own all of it. He seizes the moment when, on Christmas Eve, he accidentally gains possession of an $8,000 check the Baileys meant to deposit. The lost check would spell prison for George, who reaches his breaking point, forsakes his family and prepares to jump off a bridge.

Enter Clarence and his plan to save George. He magically transforms Bedford Falls into an alternate reality so that George can see what the world would be like if he didn’t exist. The result is a dark existence for the town and all who inhabit it.

One by one, George sees the people from his life, and each of them is in dire straits. He comes to learn that his life truly had a positive impact on countless people, and he pleads with Clarence to return his life back to normal. In a moment of jubilation, George runs through the streets of Bedford Falls thankful to have his ordinary life back.

One by one, George sees the people from his life, and each of them is in dire straits. He comes to learn that his life truly had a positive impact on countless people, and he pleads with Clarence to return his life back to normal. In a moment of jubilation, George runs through the streets of Bedford Falls thankful to have his ordinary life back.

It’s a Wonderful Cast

Fitting for a film about the importance of friends, Capra compiled a powerful cast of familiar faces, giving each a final bow as they come to George’s aid in the film’s finale.

Thomas Mitchell (Uncle Billy) was  the most accomplished in the supporting cast. Just seven years earlier, he had won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar as the drunken doctor in Stagecoach (1939). That same year, he appeared in four other classics: Gone with the Wind (1939), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939). In Wonderful Life, he’s such a lovable character we almost forget he’s the other “brother” in the Bailey Bros. Building & Loan.

the most accomplished in the supporting cast. Just seven years earlier, he had won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar as the drunken doctor in Stagecoach (1939). That same year, he appeared in four other classics: Gone with the Wind (1939), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939). In Wonderful Life, he’s such a lovable character we almost forget he’s the other “brother” in the Bailey Bros. Building & Loan.

Henry Travers (Clarence) was equally well known, having earned an Oscar nomination for Mrs. Miniver (1942) before providing comic relief in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and backing Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman in The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), which is on the marquee at the Bedford Falls movie house. His Clarence is the moral conscience of the film, providing truth, comedy and perspective.

Ward Bond (Bert the cop) had already played police officers in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941). The same year he shot Wonderful Life, he also appearance in Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946). His partner in crime, Frank Faylen (Ernie the Cabbie), had appeared in the previous year’s Best Picture, The Lost Weekend (1945). Together, the two inspired the Sesame Street characters (see pop culture below).

Ward Bond (Bert the cop) had already played police officers in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941). The same year he shot Wonderful Life, he also appearance in Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946). His partner in crime, Frank Faylen (Ernie the Cabbie), had appeared in the previous year’s Best Picture, The Lost Weekend (1945). Together, the two inspired the Sesame Street characters (see pop culture below).

H.B. Warner (Mr. Gower) had been a titan of the silent era, to the point of playing Jesus Christ in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927). But it was Capra who brought him into the “talkies,” casting him in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), directing him to a Supporting Actor nomination in Lost Horizon (1937), giving him a Best Picture platform in You Can’t Take it With You (1938) and featuring him prominently as a rival senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

H.B. Warner (Mr. Gower) had been a titan of the silent era, to the point of playing Jesus Christ in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927). But it was Capra who brought him into the “talkies,” casting him in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), directing him to a Supporting Actor nomination in Lost Horizon (1937), giving him a Best Picture platform in You Can’t Take it With You (1938) and featuring him prominently as a rival senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

The role of Violet Bick made Gloria Grahame a  star, as she earned an Oscar nomination the following year for Crossfire (147), then won the gold for The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Grahame is the sexy alternative to Donna Reed, who can’t help but win us over with her sweetness. Her chemistry with Stewart makes for some of the most romantic scenes in history, launching It’s a Wonderful Life to #8 on the AFI’s 100 Passions, just ahead of Love Story (1970).

star, as she earned an Oscar nomination the following year for Crossfire (147), then won the gold for The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Grahame is the sexy alternative to Donna Reed, who can’t help but win us over with her sweetness. Her chemistry with Stewart makes for some of the most romantic scenes in history, launching It’s a Wonderful Life to #8 on the AFI’s 100 Passions, just ahead of Love Story (1970).

Ironically, Reed had to turn darker to finally win her Oscar seven years later in From Here to Eternity (1953). It was her one and only brush with the gold, though she was nominated for four Emmys for TV’s The Donna Reed Show (1958). Still, no matter what else she accomplished in her career, Reed was grateful to be immortalized forever in Capra’s masterpiece.

“When I finished making that film, I thought perhaps I might not make any more movies,” Reed said. “I suppose I knew on some deep level that I would never have another experience in a film to equal it. … I certainly never dreamed that people would be looking at It’s a Wonderful Life every Christmas Eve for the next 35 years. Frank, I am very grateful and beholden to you for letting me be Mary Bailey.” (E)

Screen Legends: Stewart & Barrymore

Capra anchored this cast with a hero and villain that were two of the best at their craft. Is there a more recognizable leading man than Jimmy Stewart? Capra had launched Stewart’s career with back-to-back starring roles in the 1938 Best Picture You Can’t Take it With You and the all-time classic Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), where his performance was so strong that he earned a make-up Oscar the following year for The Philadelphia Story (1940). It’s a Wonderful Life was their third picture together, and it would become Stewart’s career role, as George Bailey was voted the AFI’s #9 Hero of All Time, two spots ahead of his Jefferson Smith in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

George Bailey is heroic because he’s an ordinary man who does extraordinary things. His everyday acts of kindness, courage, and honor come in spite of everything a script can throw at him. Perhaps Stewart was so good at playing George Bailey because he was so much like him in real life. In addition to his aw-shucks demeanor, many of George’s aspirations stem from Stewart’s own background. He himself had studied architecture before joining a theater company (“I want to build things”) and was later inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame (“anchor chains, plane motors and train whistles”).

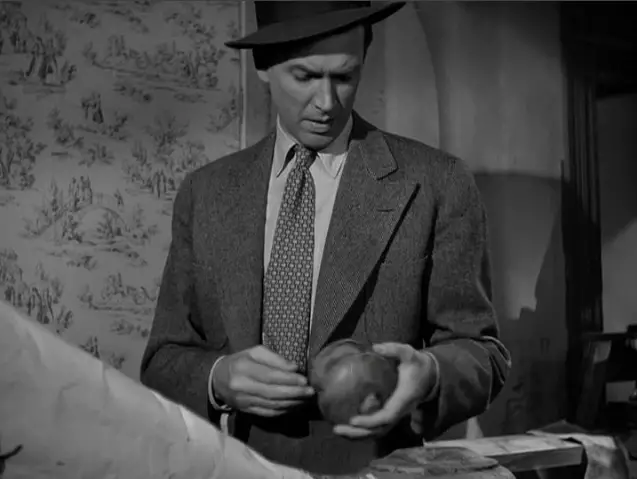

Premiere magazine voted it the #8 Greatest Performance of All Time. We believe he’s at the end of his rope as he clutches his kid to his chest; as he kicks his model bridge set; as his wild eyes prepare to launch him off a bridge. Likewise, his “second chance” joy rivals that of Alistair Sim in A Christmas Carol (1951). It’s impossible not to smile as George realizes his life is back to normal: “My mouth’s bleeding, Bert! My mouth’s bleeding! Zuzu’s petals! Zuzu’s — there they are!”

Premiere magazine voted it the #8 Greatest Performance of All Time. We believe he’s at the end of his rope as he clutches his kid to his chest; as he kicks his model bridge set; as his wild eyes prepare to launch him off a bridge. Likewise, his “second chance” joy rivals that of Alistair Sim in A Christmas Carol (1951). It’s impossible not to smile as George realizes his life is back to normal: “My mouth’s bleeding, Bert! My mouth’s bleeding! Zuzu’s petals! Zuzu’s — there they are!”

Ironically, Stewart may not have been a part of the film if it weren’t for his on-screen nemesis, Lionel Barrymore, who convinced him to do the film even though Stewart didn’t feel up for it after returning from the war. (D) Is there a more famous name in Hollywood than “Barrymore?” The brother of John Barrymore (Grand Hotel), brother of Ethel Barrymore (None But the Lonely Heart) and great uncle of Drew Barrymore (E.T.), Lionel Barrymore may have been, as Potter says, “the most talented one of the bunch.” He was also the most well known at the time, having won an Oscar for A Free Soul (1931) and having appeared in a number of popular radio programs.

“In the 1930s, listening to Lionel Barrymore play Scrooge on the radio at Christmastime was as much a holiday tradition as trimming the tree or trying to swallow fruit cake,” said Robert Osbourne of Turner Classic Movies. (A) When MGM tried bringing his Scrooge to the screen in the first talkie of A Christmas Carol (1938), Barrymore fell on another movie set, aggravating leg and hip injuries and forcing him to be replaced by Reginald Owen.

From that point on, all his roles were written to accommodate a wheelchair, hence his seated position throughout Wonderful Life. No matter, Mr. Potter might as well have been the reincarnation of Scrooge, with the same heartless attitude toward the poor earning him the title as the AFI’s #6 Greatest Villain of All Time, one spot behind Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975).

Screenplay: A Christmas Card Carol

Inspired by the short story The Greatest Gift, which Philip Von Doren Stern wrote on a Christmas card to his family in 1943, the rights were bought by RKO Pictures, who teamed with Capra’s Liberty Films to bring it to the silver screen. Screenwriters Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett helped Capra flesh it into a screenplay, along with additional scenes by Jo Swerling and uncredited input from Dorothy Parker, Dalton Trumbo and Clifford Odets. (G) Parker lends some credence to Al Bundy’s line as he watches the film in Married with Children (1987): “This must be written by a woman.”

The WGA recently voted It’s a Wonderful Life the #20 best screenplay of all time, which is only fitting because the script plays out like a Screenwriting 101 class. You need not read a fancy screenwriting book; just watch this film to learn the power of premise, character and setups-and-payoffs.

Premise. “Wait a minute. Wait a minute! Now there’s an idea!” The premise conjures memories of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, including an other-worldly being showing a mortal man pieces of his life, not to mention the protagonist’s moment of realization at a gravestone. It’s a Wonderful Life took it the next step with its own ingenious idea. Instead of gazing into a man’s past, present and future, it offered the entirely fresh experience of a seeing that man erased from existence, as if he’d never been born. We’re able to see how the absence of the protagonist affects the lives of all the supporting characters. The angel/mortal interaction inspired countless films, from Cary Grant in The Bishop’s Wife (1947) to Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987).

Characters. “My father was no businessman, everybody knows that. But neither you, nor anyone else can say anything against his character.” Movies are all about character, and Scriptwriting 101 tells you to give your main characters memorable flaws. For Mr. Potter, it’s constantly being pushed around in a wheel chair by a voiceless henchman. He’s also unique in that he’s the rare bad guy who doesn’t get caught. In real life, the greedy men rarely do. How many Bernie Madoffs never get caught? In this way, Potter is left to be judged by the audience, not by Capra. The hero-viillain relationship thus ends uniquely, with Potter thinking he’s finally got the best of George Bailey — “Happy New Year to you, in jail” — while George simply kills him with kindness: “Merry Christmas, Mr. Potter!”

Meanwhile, George’s flaw is hearing loss, Capra’s nod to fellow director William Wyler, who lost hearing in one ear while shooting a doc on bomber pilots during WWII. This accomplishes several things: (a) it shows the sacrifice and heroism of his character, diving into ice water to save his brother; (b) it introduces Mary’s love for George at a young age (“Is that your bad ear? George Bailey, I’ll love you ’til the day I die”); (c) it provides proof of Clarence’s alternate reality, as George’s hearing suddenly returns; and (d) it provides some comic relief (“That’s my trick ear; it sounded as if you said no charge.”)

Setups & Payoffs. “Something happens here that you’re going to need to remember later on.” Throughout the script, the writers plant various devices that pay off later on. The “Harry through the ice” scene is an overt setup to the cemetery scene. The “forgetful” strings on Uncle Billy’s fingers set up the lost $8,000. The frustration of the loose banister post sets up George’s new-found appreciation of it later. George’s mention of his life insurance policy to Potter sets up its disappearance with Clarence. George’s heated conversation with Mrs. Welch on the phone sets up Mr. Welch socking him at the bar. Nick’s mockery (“Look I’m giving out wings”) sets up Zuzu’s famous line. And Zuzu’s flower petals sets up their disappearance outside the bar and reappearance on the bridge.

The most important setup is George and Mary’s rock-throwing at the old Granville house:

This perfectly sets up the later scene where Mary creates an impromptu wedding night at the same abandoned house. The callback is apparent when she says, “Remember the night we broke the windows in this old house? This is what I wished for.”

America’s Internal Struggle

Of all the script’s attributes, its greatest achievement may be its ability to pack such universal truths into such uniquely American themes. It’s a Wonderful Life may very well be the most American film ever made, spanning the most consequential period of American history. George Bailey brings us through the first half of the 20th century like Forrest Gump brings us through the second. Smashing windows of the past, George and Mary can say the same as Gump and Jenny: “Sometimes I guess there just aren’t enough rocks.” The film covers five eras in particular:

- Turn of the Century: Young George and his friends play outdoors, Mr. Gower experiments with new medicines, Gower’s son dies of influenza, Mr. Potter rides around in a horse-drawn carriage, and George reads National Geographic Magazine.

- Roaring Twenties: George and Mary dance the Charleston with the Class of 1928, the Baileys have a black house servant, George wears a “leatherhead” football uniform, just eight years after the founding of the first pro football league.

- The Great Depression: Victrolas and telephones are now mainstays in most U.S. homes, like those in the Hatch house, Sam Wainwright gets in on the ground floor of making plastics out of soybeans, George prevents a bank run at the Building and Loan.

- World War II: George (4-F on account of his ear) fights the “Battle of Bedford Falls” with rubber drives and air raids, Mary runs the U.S.O., Ma Bailey and Mrs. Hatch sew for the Red Cross, Mr. Gower and Uncle Billy sell war bonds, Sam sells plastic hoods for war planes, Potter runs the draft board, Bert gets the Silver Star fighting in North Africa, Ernie parachutes into France, Marty captures a strategic bridge, and Harry shoots down 15 Japanese planes to save the lives of countless men on a Navy transport.

- Post-War: Contemporary 1946, the men return home, George and Mary contribute to the baby boom, Bailey Park becomes a regular Levittown, Sam Wainwright explores the future of plastics, Harry is awarded the Medal of Honor.

British film critic David Thomson admits he didn’t appreciate It’s a Wonderful Life while living in the U.K., but got it after he moved to the States and saw how much of an institution it was around the holidays. “Because that movie is so beautifully made, so rich in texture and nuance, it set me on a line of thought that wonders if some of the most central American films do not offer an uncanny conjuring of ‘genius’ and the unwholesome — I would put The Godfather, Citizen Kane, The Searchers, and Taxi Driver (at least) in the same category: terrific movies with their own plunge into the abyss.”

Is Capra’s plunge into Bedford Falls really so different from David Lynch’s dive into Lumberton in Blue Velvet (1986)? Outwardly they appear on opposite ends of the spectrum, but at their core, both pry up their own white picket fences to investigate the darkness underneath, the same fences George has trouble opening.

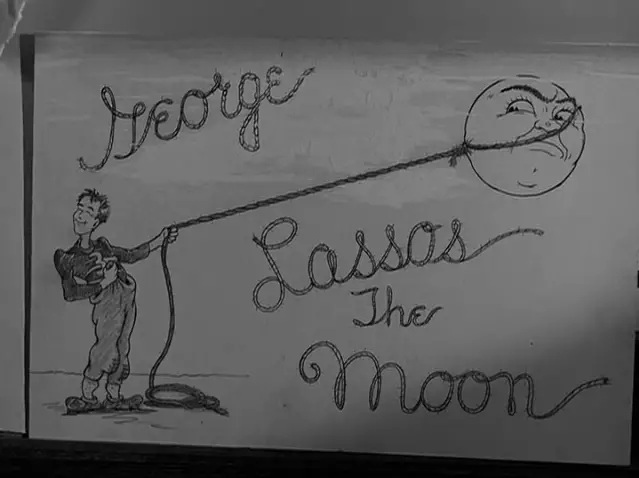

As critic Robin Wood writes, Capra recognizes explicitly that “behind every Bedford Falls lurks a Pottersville, and implicitly that within every George Bailey lurks an Ethan Edwards of The Searchers.” (B) How fitting that both Thomson and Wood mention Ford’s western. For within George Bailey lies the same dilemma of our cowboy heroes, that which makes the Western a uniquely American genre. George wants to explore, but is faced with the lure of settling down on the homestead. How ironic that the very symbol of this domesticity (Mary) draws a picture titled, “George Lassos the Moon.” It’s classic frontier imagery applied to the final frontier, only George never gets to explore it. Rather than lassoing the moon, he lassos a stork.

The internal struggle of America is right there in George Bailey’s angst. Should we engage in overseas adventurism, or turn inward toward the domestic? Should we focus on the rugged individualism of the private sector, or the social safety nets of a compassionate public sector? And should we chase the notion of exceptionalism, or be an important piece of a larger whole? Capra seems to say that America works best when both parts are in their proper proportions. In a world of bank bailouts and home foreclosures, It’s a Wonderful Life is just as relevant today as it was in 1946.

The internal struggle of America is right there in George Bailey’s angst. Should we engage in overseas adventurism, or turn inward toward the domestic? Should we focus on the rugged individualism of the private sector, or the social safety nets of a compassionate public sector? And should we chase the notion of exceptionalism, or be an important piece of a larger whole? Capra seems to say that America works best when both parts are in their proper proportions. In a world of bank bailouts and home foreclosures, It’s a Wonderful Life is just as relevant today as it was in 1946.

On the one hand, the film celebrates the principles of responsible capitalism through the entrepreneurial spirit of small businesses like the Bailey Building & Loan: “You’re thinking of this place all wrong! As if I had the money back in a safe. The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house, right next to yours. And in the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Macklin’s house, and a hundred others. Why, you’re lending them the money to build, and then, they’re going to pay it back to you as best they can.”

On the other, it urges the need for social responsibility and helping the less fortunate: “This town needs this crummy one-horse institution if for no other reason than to keep people from crawling to Potter.” Capra does not view personal liberty and collective compassion as mutually exclusive ideals.

This theme of compassion manifests itself in two ways, both in the religious construct and the social welfare construct. The religious themes are undeniable. The film opens with the soft piano notes of “O Come All Ye Faithful” set to a montage of prayers, including Martini’s wish, “Jesus, Joseph and Mary, help my friend, Mr. Bailey.” From here, we go to a matte of the cosmos with the voices of heavenly bodies flickering with dialogue — the type of stuff that dates the film. Later, in his deepest despair, George breaks down and prays for help, “I’m not a praying man, but if you’re up there and you can hear me, show me the way.” When he’s socked in the mouth, he says, “This is what I get for praying,” but the skepticism doesn’t last long, as a guardian angel saves him to a chorus of “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.” Doesn’t get more religious than that.

Meanwhile, the film also preaches a message of social welfare, pitting the Baileys of the world against the Potters. It’s a battle between the common folk and the wealthy, the merciful and the ruthless, the Bailey Parks and the Potter Slums. We smile as George and Mary help the immigrant Martini family get their first home —“Bread: that this house may never know hunger” — because it promotes compassion toward the little guy.

This is a message that can be embraced by all political stripes, from Occupy Wall Street to the Tea Party, which I contend have more in common than they think (you won’t find much difference between this 2009 Tea Party country song and this 2011 Occupy protest ad). Capra captured this populism during George’s boardroom speech on the future of the Building and Loan:

GEORGE: Just remember this, Mr. Potter, that this rabble you’re talking about, they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community. Well, is it too much to have them work and pay and live and die in a couple of decent rooms and a bath? Anyway my father didn’t think so. People were human beings to him, but to you — a warped, frustrated old man — they’re cattle. Well in my book he died a much richer man than you’ll ever be.”

The speech recalls Stewart’s filibusters on the floor of the Senate in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: “I wouldn’t give you two cents for all your fancy rules if, behind them, they didn’t have a little bit of plain, ordinary, everyday kindness. And a little lookin’ out for the other fella, too.”

It also recalls Gary Cooper’s speech in Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941), where the protagonist’s philosophy sparks an entire political movement: “To most of you, your neighbor is a stranger, a guy with a barking dog and a fence around him. Now you can’t be a stranger to any guy who’s on your own team. So tear down that fence that separates you. You’ll tear down a lot of hate and prejudices. I know a lot of you are saying to yourself: ‘He’s asking for a miracle!’ Well, you’re wrong. It’s no miracle! I see it happen once every year at Christmastime. Why can’t that spirit last the whole year round? Gosh, if it ever did, we’d develop such a strength that no human force could stand against it.”

“Tonight I’m gonna tell you the real secret of the whole thing,” Capra said during his AFI Lifetime Achievement Award speech. “The art of Frank Capra is very, very simple. It’s the love of people. Add two simple ideals to this love of people — the freedom of each individual and the equal importance of each individual — and you have the principle upon which I based all my films.” (E)

Perhaps Capra had such an affinity for the American Dream because he had lived it. Born in Bisacquino, Sicily, his family emigrated to America on the ship Germania in 1903. Capra romantically describes seeing the Statue of Liberty for the first time: “Thirteen days of misery. And then the ship stopped, and my father grabbed me and carried me up the steep iron stairs to the deck. And then he shouted, ‘Chico, look at that!’ At first, all I saw was a deck full of people on their knees crying and rejoicing. My father cried, ‘That’s the greatest light since the Star of Bethlehem.’ I looked up and there was the statue of a great lady, taller than a church steeple, holding a lamp over the land we were about to enter. And my father said, ‘It’s the light of freedom, Chico. Remember that. Freedom.’ … For America, just for living here, I kiss the ground.” (E)

Capra’s Independent Film

While Capra had a much larger budget than John Cassavettes, Jim Jarmusch and the others we typically associate with the term “independent,” It’s a Wonderful Life is a classic example of the independent film. It features a filmmaker who started his own production company, found a story that spoke to him, helped write the screenplay, produced and financed the project and directed it with auteur vision. It was the first and only time he tackled all of these steps, and for this, critic/filmmaker Peter Bogdonavich called It’s a Wonderful Life Capra’s independent masterpiece.

“It may well be Capra’s masterpiece, but it’s more than that,” Wood said. “Like all the greatest American films — fed by a complex generic tradition and, beyond that, by the fears and aspirations of a whole culture — it at once transcends its director and would be inconceivable without him.” (B)

Capra co-founded his production company, Liberty Films, with Samuel Briskin, the former production head at Columbia pictures, in April 1945, just before production of It’s a Wonderful Life. Within months, George Stevens (Shane) and William Wyler (The Best Years of Our Lives) had become partners, forming a “liberty” rebellion against the studio system, reflected in George Bailey’s battle against Mr. Potter.

The venture was short lived, as the box office failure of Wonderful Life forced the company to be sold to Paramount in May 1947. In his famous autobiography, The Name Above the Title, Capra wrote that he had formed Liberty Films to: “(1) influence the course of Hollywood films, (2) make four former Army officers independently rich, and (3) virtually prove fatal to my professional career.” (F) Still, each time that bell rings at the beginning and end of It’s a Wonderful Life, we’re reminded of its importance.

Capra’s independent status applies to more than just his production company. It also applies to his rule-breaking attributes, no matter how shrouded in schmaltz. I gladly award full directing points, even in the face of some jarring cuts, namely when Billy loses the money in Potter’s newspaper. It may have been the best the editor William Hornbeck could do with what Capra shot, but both were nominated for Oscars, and Capra won the Golden Globe for directing.

“The films were his films, made his way,” George Stevens Jr. said. “Frank was never found taking his hat off to conventional wisdom, market research, the front office or the latest trend. At a time of uncertainty in our country and in our industry, we have much to learn from a man who came here an immigrant and enriched a new art form with his ideas and his ideals.” (E)

Academia refuses to put Capra in the class of Hitchcock, Ford or Fellini, and they may be right when discussing Capra’s overall career. Too many of his movies dive into Capra-corn and rely more on written monologues than directing techniques. However, with It’s a Wonderful Life, I firmly believe you see a master director at work. As you’ll see in the numerous examples below, Capra breaks rules, raises audience awareness to the apparatus of the camera and packs his frame with symbolic mise-en-scene.

“May I say a word to this new generation?” Capra said to deaf ears in 1982. “Don’t follow trends. Start trends! Don’t compromise. Believe in yourself! Because only the valiant can create. Only the daring should make films. And only the morally courageous are worthy of speaking to their fellow man for two hours and in the dark.” (E)

Freeze Frames & Focus Pulls

Capra’s first attempt at calling out his own medium is the focus pull at the start of George’s flashback, where a blurry image comes into clarity as Clarence first sees George’s childhood. It seems like a trick to bring us into the backstory, but when you stop and think about it, it’s actually one of the most self-reflexive directorial commentaries one can make about the film medium. It’s a reminder that the director shows us only what he wants us to see, and the cinematographer (with the help of an Assistant Cameraman) has to bring the image into focus, or we have no movie.

Here, Capra takes us through the entire process, as God (the filmmaker) enlists the help of Joseph (the cinematographer) to slowly bring George’s flashback (the movie) into focus for Clarence (the audience). He speaks to us as if we’re eager film students wanting to learn how to see movies in a new way, through the cinematic eye, through the film theory perspective: “Now look, I’ll help you out. … If you ever get your wings, you’ll see all by yourself.”

He follows the focus pull with a revolutionary freeze frame on George Bailey’s face. Audiences must have wondered the same thing as Clarence: “What’d you stop it for?” It was the first example of doing this that I know of, arriving 4 years before Joseph Mankiewicz did it in All About Eve (1950), 13 years before Francois Truffaut did it in The 400 Blows (1959), 23 years before George Roy Hill did it in Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969) and 44 years before Martin Scorsese did it in Goodfellas (1990). Of all these examples, Capra is the only one who starts with a live shot, freezes it, then unfreezes it all in a row. The other films use the freeze frame to launch into opening credits (GoodFellas), transition into the backstory (Eve), or kick off the end credits (400 Blows, Butch & Sundance).

Power Reversal

Capra also demonstrates the importance of the spatial relationship between characters. This is very apparent in a scene in Potter’s office, where Potter purposely has a low chair installed so that he looks down on the person sitting across from him.

Mise-en-Scene: Everywhere a Sign

Spatial relationships are but one part of Capra’s overall mise-en-scene. He requires us to scan every inch of every frame, like in this beautiful composition of Young George and Mr. Gower behind the drugstore pill bottles. Note the way a concerned George stares at a potentially poisonous pill bottle, while a distraught Gower stares at the photo of his dead son.

Capra similarly uses a photo of George’s dead father at the Bailey Building & Loan. It hangs atop a sign that reads, “All you can take with you is that which you’ve given away,” influential on Darabont’s use of the Warden’s sign in The Shawshank Redemption (1994).

Another sign hangs in the background of the bank run scene. In giant letters, it reads, “Own Your Own Home,” the very core of the American Dream.

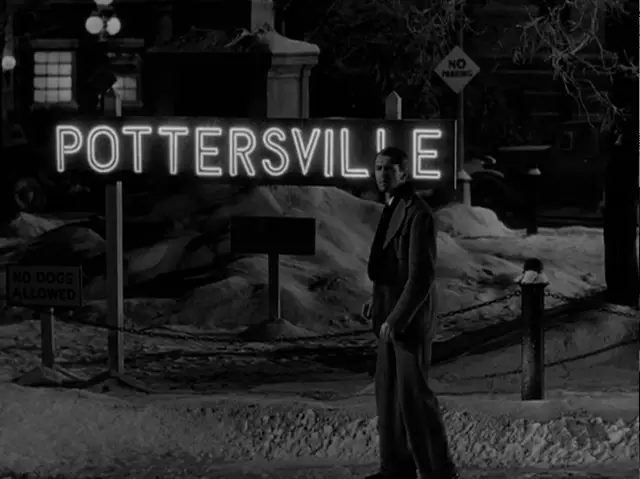

Sometimes, there are even signs behind the signs. Note the banner behind the “You Are Now in Bedford Falls” sign, reading a message of warmth and freedom (“Welcome Home Harry Bailey”). Compare that to the signs behind the “Pottersville” sign, reading messages of oppression (“No Parking” and “No Dogs Allowed”).

Capra similarly uses mise-en-scene to show a contrast on the walls of the Bailey house. There’s a scene where Mary is shown wallpapering the house, as the narrator says, “Day after day [Mary] worked her way to remaking the old Granville house into a home. Night after night, George came back late from the office.” Note the standard, floral wallpaper here.

Now, compare that to the wallpaper in the scene where George comes home stressed and “at the end of his rope.” Now the wallpaper features an anchor pattern, recalling something a youthful George once said, “You know the three greatest sounds in the world? Anchor chains, plane motors and train whistles.” Only now, George is middle-aged and hasn’t chased his dreams. These wallpaper anchors are a reminder of this missed opportunity. They symbolize his home as an “anchor” weighing him down and allowing no escape. They are the weight at the end of his rope.

The Divine Divider

A most fascinating use of mise-en-scene comes in the scene where Stewart and Clarence dry off after their dive into the river. Note the clothesline separating Clarence’s spiritual world (above the line: heaven) with George’s mortal world (below the line: Earth).

Was this intentional? If only Capra had used a Biblical analogy on a clothesline before, we might have grounds for a case. Oh wait, he did. Your honor, I present the “Walls of Jericho” separating Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night (1934).

Happy New Year: In Jail

“Do you realize what this means? It means bankruptcy and scandal and prison!” Capra foreshadows George’s financial danger the first time we learn the bank doesn’t have enough funds, during the Great Depression. As George stands with his customers outside the bank, he looks through the vertical bars of the bank’s front gate.

This comes to fruition when Uncle Billy loses the $8,000. He stands before the bank teller, smiling, while Capra knows a truth that we the audience don’t even know yet: Billy has lost the cash. The cinematic eye is conspiring with fate to say that Uncle Billy is about to be in serious trouble, and he doesn’t even know it.

The bars are also used to show George’s feelings of entrapment in his ordinary life. In the scene where George finds out Mary is pregnant (his ultimate domestic trap), he staggers back into his bedroom and replays his regrets in his head via voiceover. As he climbs into bed and Mary reveals her pregnancy, Capra presents the shadows of jailbars behind him. Of course, perspective is everything, as George later says, “Isn’t it wonderful? I’m going to jail!” Here, however, he’s feeling as trapped as can be.

Bedford Noir

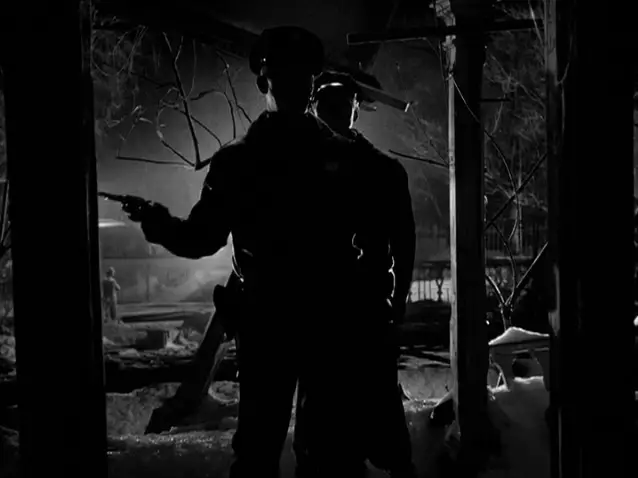

The above scene is our first hint of the sinister lighting to come in George’s alternate reality. The entire alternate reality of Pottersville becomes an exercise in film noir. The lighting of the abandoned Granville house rivals anything that year in The Big Sleep (1946). Cinematographers Joseph Biroc and Joseph Walker deserve a mountain of credit for their chiaroscuro lighting. I’d like to think Capra is referencing them in this scene, as Clarence tussles on the ground with Bert and yells “Joseph! Joseph!” Two Josephs.

Direct Camera Address

This noir stretch provides the most stand-out shot in the entire film. It comes the minute George is not recognized by his own mother. Here he begins to realize he’s not dreaming; that this alternate reality actually exists. Capra presents the moment by breaking the fourth wall, taking the technique of “direct camera address” introduced by Thomas Edison and Edwin S. Porter in The Great Train Robbery (1903) and adding the same actor head-turn that Ingmar Bergman used later in Persona (1966).

With a locked off static camera in the front yard facing the house, George starts small in the background, then runs toward the camera. He settles into a close-up looking frame left, then gives a wild-eyed turn to stare directly at the camera. You can tell Capra intended the shot to last longer, as we cut to a reaction shot of Clarence, then back to the shot of George completing his head turn.

Leaving the Frame

The direction of George’s head turn takes on more meaning when you consider its relation to a previous scene outside the same house with the camera in the same position. As Ma Bailey tries to convince George to “call on” Mary, she points him toward frame right in the direction of Mary’s house. George exits frame right, leaving the frame, but the camera holds its ground and the film keeps rolling. Suddenly, George reappears and exits frame left. This ties perfectly into the direction of George’s head turn in the above “direct camera address,” as he slowly turns to the right — and then pursues Mary in the next scene.

The “leaving the frame” idea also allows for a happy accident. As Uncle Billy exits the frame, we hear a loud crash off screen. Turns out a crew member actually broke something on set! Rather than a Christian Bale freakout, Mitchell kept his cool and ran with it, shouting: “I’m all right, I’m all right!” Stewart had the instincts to play off it. Capra had the sense to leave it in the film, and even paid the clumsy crewmember a $10 bonus for “improving the sound.” (D)

Single Take: Romance in Real Time

The above scene is just one brilliant use of the long “single take.” Capra’s best use of the technique comes later in the scene where George visits Mary. Note the masterful blocking as George and Mary wind up cheek to cheek sharing the telephone. Letting it play in “single take” is much more powerful than cutting the shot into pieces. Stewart was actually nervous about the kiss because it was his first since returning to Hollywood after the war. He nailed it in one unrehearsed take, and was so passionate that part of it had to be cut to please the censors. (D)

A Smashing Soundtrack

Watch the above scene again. Did you notice Capra’s other brilliant commentary on the filmmaking apparatus? He goes so far as to mess with the soundtrack, as Mary literally smashes the diagetic sound of the record player! The scene starts with no music, but when Mary puts “Buffalo Gals” on the Victrola, we suddenly have a soundtrack to the scene. After George’s jerk comments, she smashes the record, and the soundtrack stops.

Capra uses “Buffalo Gals” as a leitmotif throughout the entire film to symbolize George and Mary’s love: (a) played by a high school band as Mary and George first slow dance at Harry’s graduation party; (b) sung by George and Mary during the famous “rope the moon” scene; (c) played on Mary’s record player as she welcomes George into her house; (d) Mary singing it just before announcing her pregnancy; and (e) during the end credits.

Capra similarly uses the leitmotif of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” for Clarence. It’s all orchestrated by four-time Oscar-winner Dimitri Tiomkin, best known for his score to High Noon (1952). In Wonderful Life, he effortlessly transitions from the cheer of Christmas to the dark depths of Pottersville.

Visuals & Effects

While Tiomkin dominates the soundtrack, the film’s visuals are an achievement all their own. The effect of Clarence disappearing holds up well to this day:

Still, the greatest visuals come from the Art Department in the construction of the entire town of Bedford Falls. The set was built over two months, spanning four acres of the RKO Encino Ranch. It featured 75 stores and buildings, a main street, a factory district and a large residential and slum area. Main Street alone — the road George famously runs down — stretched 300 yards, the length of three football fields. (D) Maybe George was, in fact, “the football type.”

The elaborate set makes the town just as much a character in the film as George or Mary. The storefronts also help draw a sharp contrast between the quaint wholesomeness of Bedford Falls and the flashing neon of Pottersville. Capra affords the town its own reaction shots as George runs through the streets, shouting, “Merry Christmas movie house! Merry Christmas Emporium! Merry Christmas you wonderful old Building & Loan!”

Pop Culture

It’s a Wonderful Life references show up constantly in other films. You’ll find them most in other holiday movies. In National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989), the Griswold kids watch it on TV, while Clark deals with a loose banister post by dicing it with a chainsaw. In Home Alone (1990), the McCalister family watches Wonderful Life dubbed in French as they sit in Paris. And in Elf (2003), Will Ferrell stands on a snowy bridge about to jump before a figure from the heavens drops in to save him.

The references come not just in Christmas movies. In The Exorcist III (1990), Kinderman and Dyer see the film at a movie theater that displays the poster. Later, the killer uses blood to write the title on a wall. In Spawn (1997), The Clown tells Spawn that he’ll be the angel Clarence and Spawn can be Jimmy Stewart. In Frequency (2000), James Caviezel is not recognized by the woman he loves, just like Stewart. In Donnie Darko (2001), Jake Gyllenhaal sees vision of “the world without me” and decides whether or not to commit suicide. And in Shrek Forever After (2010), Shrek learns what the world would be like had he not been born. Wim Wenders references the films with his angels in Wings of Desire (1987), which was remade as City of Angels (1998).

Entire plot elements appear to echo through time — a pregnancy announcement (Giant), promises of a future in plastics (The Graduate), cutting short one’s honeymoon to fulfill a town duty (High Noon, Touch of Evil). Most of all, in Back to the Future II (1989), the alternate reality of Biff’s Tannen Town is a direct reference to Capra’s Pottersville. Like George, Marty McFly has a shocking moment where he sees the death date of a loved one on a cemetery headstone.

After hilariously impersonating Jimmy Stewart in his standup routines, Jim Carrey made ultimate reference to the movie in Bruce Almighty (2003), where he literally throws a lasso around the moon and pulls it down for Jennifer Aniston.

The references also come on television. Sesame Street‘s “Bert and Ernie” were named after Bert the Cop and Ernie the Cab Driver. The show called attention to this fun fact in Elmo Saves Christmas (1996), where Ernie and Bert watch the film on a portable TV and are amused to hear their names.

Other TV homages on That 70s Show, The Simpsons, 3rd Rock from the Sun, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Nanny and Family Guy. In sketch comedy, Saturday Night Live had Dana Carvey acts out the supposed “Lost Ending” of It’s a Wonderful Life, while Chappelle’s Show had a skit called “It’s a Wonderful Chest.” In The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (1990), Tom Jones appears and shows Carlton what the world would be like if he hadn’t been born. There’s a similar episode in Nickelodeon’s Rugrats.

It’s a Wonderful Second Life

As often as it’s referenced today, the film was largely overlooked upon release. It recouped just $3.3 million of its $3.7 million budget, got mixed reviews and convinced the studios “that Capra was no longer capable of turning out the populist features that made his films the must-see, money-making events they once were.” (C)

Just like The Shawshank Redemption, It’s a Wonderful Life was nominated for multiple Oscars but shut out by the Academy. While Shawshank relied on VHS sales to give it second life, Wonderful Life relied on Stewart and Reed reprising their roles on radio in 1947, first on “The Lux Radio Theatre” and then on “Camel Screen Guild Theatre.” (D) That all changed with the advent of television — and the clearing of some legal hurdles.

“By the 1960s, the film’s copyright expired which opened the floodgates for a ‘public domain’ version to be circulated for cheap and frequent television broadcast,” writes critic Karen Krizanovich. “Repeated heavily around the holiday season, it became a mainstay of wholesome family viewing. As an emotional touchdown for several generations, public broadcasting stations in the 1970s cemented the film’s reputation of quality by scheduling it against the commercial networks’ crass and materialistic holiday fare.” (G)

Thankfully, the film outlasted Ted Turner’s fad of “colorizing” movies, which Capra and Stewart both hated. It’s now shown in its original black-and-white glory. Today, the public rates Wonderful Life a powerful 8.7 on IMDB, while the critics give it a 95% on rottentomatoes. The film also ranks in the top tier of countless best lists, and is one of just several movies Chuck Workman gives a title card in his 100 Years at the Movies montage.

Still, I worry the very medium that brought the film fame now threatens to dilute its greatness. Countless viewings may cause us to take it for granted, and constant commercials reduce the story’s momentum. The film should be viewed in its entirety without interruption. When you do this, It’s a Wonderful Life delivers on its payoff every time, with the culminating scene bringing chills even after all these years.

Final Thoughts

And yet, after all these years and dozens of viewings later, I keep returning to the idea posed at the start of this review, the long plunge into darkness, the reason for the initial mixed reviews, and the element that divides those who love the film from those who can’t sit through it.

Is it an uplifting yarn or a tale of buyer’s remorse? I suppose it depends on your worldview. The film no doubt gives The Wizard of Oz (1939) a run for its “there’s no place like home” money, serving as the antithesis of that great scene from Good Will Hunting (1997) where Ben Affleck tells Matt Damon, “If you’re still here in 20 years, I’ll kill you.” Rather than Damon hopping in a car out to California, Stewart crashes his car into a tree that’s as deeply rooted in Bedford Falls as his own fate. I shudder to think how many people didn’t pursue their dreams because they watched It’s a Wonderful Life.

Then I stop and shake myself and choose to view it as more than that. For in order to make such a film, Capra had to leave his comfort zones and seek new shores. To achieve this work of art and entertainment that has inspired millions, he had to take the road less traveled. And as much as we see George trapped at home, we must know Harry Bailey is out traveling the world, reuniting with his brother over the joy of special occasions.

Ultimately, it comes down to perspective. For those content with their lives, the film is annual reassurance. For those yearning to branch out on their own, it’s a cautionary tale against life’s “what ifs.” But in both interpretations, one constant remains. Capra reminds us what it means to have true wealth on this planet: friends and family who will do anything for you at the drop of a hat. People spout off “money isn’t everything” with cliched frequency, but It’s a Wonderful Life is celluloid proof of the idea. To realize that theme, after two hours of darkness, and break gloriously into the light of Capra and Christmas, Stewart and snowflakes, a crowd of old friends and “Auld Lang Syne,” may be the closest to a miracle we’ll ever see on film.![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Robert Osborne, Turner Classic Movies intro to A Christmas Carol (1938)

CITE B: Robin Wood, “Ideology, Genre, Auteur,” Film Theory & Criticism, p. 720-723

CITE C: Mark Eliot, Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2006.

CITE D: IMDB Trivia

CITE E: Frank Capra’s AFI Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony

CITE F: Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title, p. 372.

CITE G: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die