Director: George Stevens

Writers: Theodore Dreiser (book), Patrick Kearney (play), Michael Wilson, Harry Brown (screenplay)

Producers: George Stevens, Ivan Moffat

Photography: William C. Mellor

Music: Franz Waxman

Cast: Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, Shelly Winters, Anne Revere, Keefe Brasselle, Fred Clark, Raymond Burr, Herbert Heyes, Shepperd Strudwick, Frieda Inescort, Kathryn Givney, Walter Sande, Ted de Corsia

![]()

Introduction

I was 20 when I fell for Elizabeth Taylor. It was during one of my first internships at The Baltimore Sun, when we heard the actress was on her death bed. Film critic Michael Sragow and multimedia editor Jo Parker (now at CNN) had me compile a tribute video, filled with the cheesy transitions of a first-time editor. Thus my first explorations of classic Hollywood came with my first explorations of Taylor. I was a sucker for those breathless lines and purple eyes, and I quickly realized there was so much more to Taylor than the diamonds and celebrity home-wrecking I’d heard about.

She wound up living for six more years, and it became a running joke at The Sun that my montage was still sitting on the shelf. By the time it finally ran in 2011, giving her “A Place in the (Baltimore) Sun,” I had hoped the day would never come. I had grown totally endeared to her work, such that her passing recalled her teary-eyed farewell to Monty Clift: “It seems like we always spend the best part of our time, just saying goodbye.”

That line came from the film that captivated me more than any in her career, A Place in the Sun, which also introduced me to the work of prolific director George Stevens. He had actually finished shooting the film in 1949, but Paramount held off releasing it until 1951 so that it wouldn’t have to compete with Billy Wilder’s masterpiece Sunset Blvd. (1950).

Paramount waited until the next Oscar cycle, where the film was a Best Picture favorite, along with Elia Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Ironically, those two films split the vote, allowing MGM’s An American in Paris (1951) to slide in for the win. (A) Still, the strategy wasn’t in vain. A Place in the Sun bagged six Oscars, including Best Director (Stevens) and Best Screenplay (Michael Wilson, Harry Brown). Today it’s remembered as the first in Stevens’ “American Trilogy,” joining his classic western Shane (1953) and his epic treatise on southern racism in Giant (1956). (B)

![]()

Plot Summary

The film is based off Patrick Kearney’s play from Theodore Dreiser’s novel, An American Tragedy, inspired by a 1906 New York murder case where Chester Gillette killed his pregnant wife Grace Brown. (B)

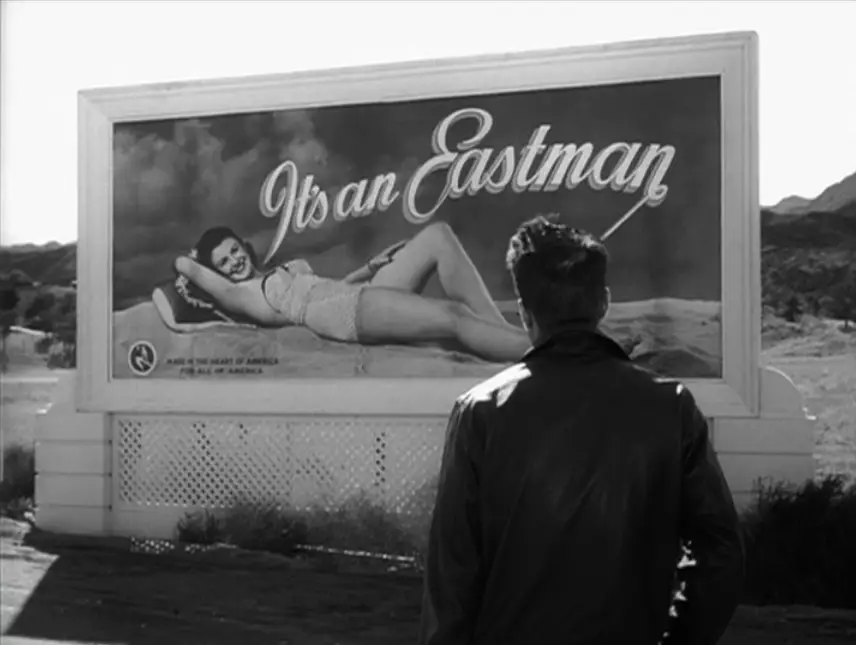

We first meet working-class drifter George Eastman (Montgomery Clift), named after the founder of Kodak, as he hitchhikes his way to his wealthy uncle, Charles Eastman (Herbert Heyes). The Eastman name is well known, like having Trump, Rockefeller or Ford as a father, but it seems George has enjoyed none of the privileges — until now.

We first meet working-class drifter George Eastman (Montgomery Clift), named after the founder of Kodak, as he hitchhikes his way to his wealthy uncle, Charles Eastman (Herbert Heyes). The Eastman name is well known, like having Trump, Rockefeller or Ford as a father, but it seems George has enjoyed none of the privileges — until now.

His uncle takes him in and gives him a job on his assembly line, where nine out of every 10 workers are female. Company policy strictly prohibits the male workers from getting involved with the females, but that doesn’t stop George from romancing his lower-class co-worker, Alice Tripp (Shelly Winters). They sneak around and see each other, even consummate, but George must keep it a secret so he doesn’t lose his job.

His uncle takes him in and gives him a job on his assembly line, where nine out of every 10 workers are female. Company policy strictly prohibits the male workers from getting involved with the females, but that doesn’t stop George from romancing his lower-class co-worker, Alice Tripp (Shelly Winters). They sneak around and see each other, even consummate, but George must keep it a secret so he doesn’t lose his job.

In what couldn’t be worse timing, George falls head over heels for the beautiful Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor), a family friend he meets at a party. This girl is the complete opposite of the mousy Alice. She is refined, cruises around in a convertible, and her Vickers family name rings of wealth. She’s like Paris Hilton, only with class. They dance together, long into the night, and it’s clear Angela feels about George the same way he feels about her — that they are soulmates.

In what couldn’t be worse timing, George falls head over heels for the beautiful Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor), a family friend he meets at a party. This girl is the complete opposite of the mousy Alice. She is refined, cruises around in a convertible, and her Vickers family name rings of wealth. She’s like Paris Hilton, only with class. They dance together, long into the night, and it’s clear Angela feels about George the same way he feels about her — that they are soulmates.

Just as George promises to visit Angela at her lake house, he discovers that Alice has a baby in the oven. Alice also finds out about Angela and forbids him to see her again. She even threatens to kill herself if George will not drop everything and marry her. So he agrees, but in the back of his mind, he’s formulating a plan. What if he took Alice out onto a lake in a boat? What if he drowned her, faked his own death and ran off with Angela? Could he get away with it? More importantly, could he actually go through with murder?

Just as George promises to visit Angela at her lake house, he discovers that Alice has a baby in the oven. Alice also finds out about Angela and forbids him to see her again. She even threatens to kill herself if George will not drop everything and marry her. So he agrees, but in the back of his mind, he’s formulating a plan. What if he took Alice out onto a lake in a boat? What if he drowned her, faked his own death and ran off with Angela? Could he get away with it? More importantly, could he actually go through with murder?

These questions effectively transform the last act of the film into a courtroom drama, begging the question: is there really a difference between the sins of one’s actions and the sins of one’s heart?

These questions effectively transform the last act of the film into a courtroom drama, begging the question: is there really a difference between the sins of one’s actions and the sins of one’s heart?

![]()

A Killer Cast

There to hammer home that point is the District Attorney, played brilliantly by Raymond Burr in a role that inspired his title role in the TV court drama Perry Mason (1957). His prosecution of Monty Clift for murder came just three years before his character, Mr. Thorwald, committed murder in Rear Window (1954).

Joining him is Anne Revere, who won an Oscar playing Taylor’s mom in National Velvet (1944). A descendant of Paul Revere, Anne had her own political struggles, as McCarthyist Hollywood blacklisting made Sun her last role for 19 years.

Joining him is Anne Revere, who won an Oscar playing Taylor’s mom in National Velvet (1944). A descendant of Paul Revere, Anne had her own political struggles, as McCarthyist Hollywood blacklisting made Sun her last role for 19 years.

Still, these two roles are mere appetizers to the three-part main course — that powerful trio of Clift, Taylor and Winters. If A Place in the Sun has a place in history, it’s for launching some of the biggest stars of a generation.

![]()

Clift: The Essence of Cool

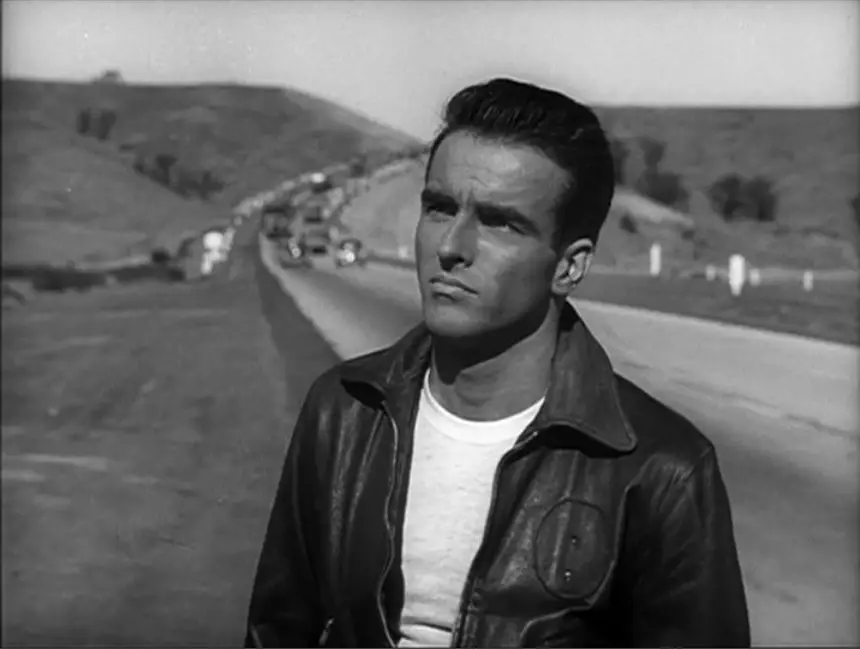

After Clift’s career was born alongside John Wayne in Red River (1948), his status as a leading man was born in A Place in the Sun. The film earned Clift his first Oscar nomination, losing to the veteran Bogart for The African Queen (1951), but landing him the lead role in the Pearl Harbor romance From Here to Eternity (1953). Unfortunately, his star fizzled out quickly, due to his alcohol abuse and increasingly bad eyesight, leaving many of his roles to instead go to James Dean and Marlon Brando in a new generation of cool. You can see his presence as he does a slow turn in his leather jacket in the opening shot.

Better yet, watch the way he nails a trick pool shot with the cue behind his back. There are no cuts in that scene! It’s every bit as impressive as Hepburn sinking that putt in Bringing Up Baby (1938).

Better yet, watch the way he nails a trick pool shot with the cue behind his back. There are no cuts in that scene! It’s every bit as impressive as Hepburn sinking that putt in Bringing Up Baby (1938).

But the cool is not all Clift has to offer. He does some serious acting here. His character is a bundle of nerves, literally shaking in the knowledge that he’s in a forbidden, deadly love affair. Word has it that Clift prepared for the climax by spending a night locked in San Quentin Penitentiary, and such preparation has us believe every bit of his performance. (C)

There are times in the film where Clift doesn’t have to say a word, and we can just see the wheels turning in his head. Taylor perhaps gave him the ultimate compliment, crediting his performance for teaching her that acting is more than just something you show up and do, that it is a learned craft you put real work into. (D)

There are times in the film where Clift doesn’t have to say a word, and we can just see the wheels turning in his head. Taylor perhaps gave him the ultimate compliment, crediting his performance for teaching her that acting is more than just something you show up and do, that it is a learned craft you put real work into. (D)

![]()

Lovely Liz & The Winters Complex

If Taylor was unsure of herself while filming A Place in the Sun, you wouldn’t know it. She’s a natural, and all at age 18. It was only eight years before that she was the 10-year-old co-star of Lassie Come Home (1943), followed by her biggest child hit, across Mickey Rooney in National Velvet (1944). After Spencer Tracy married her off in Father of the Bride (1950), the stage was set for Taylor’s first adult role in A Place in the Sun. My how she grew up.

If you’ve never seen Liz Taylor in her prime, brace yourself. She’s a knockout. David Thomson writes, “In the 50 years since, has any movie actress been so blatant about extraordinary beauty? Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman is the only case I can think of.” (F)

Still, it wasn’t Taylor who earned the Best Actress nomination. That went to Winters, the first of her career. Though she eventually lost to Streetcar‘s Vivien Leigh, she would reteam with Stevens to win the statue a few years later in The Diary of Anne Frank (1959).

As for A Place in the Sun, her role as Alice went entirely against her place in Hollywood, where she was being groomed as a sex symbol. When auditioning for the role, she dyed her hair brown and wore raggedy clothes to the point that Stevens didn’t even recognize her in his office. (C) The great irony is, of course, that Winters, who intentionally played against type, actually became typecast in that new image, even meeting the same watery fate in The Night of the Hunter (1955). Winters said that for years after the film, she drove around in white Cadillac convertibles, like that which Taylor drove in the film, as therapy for an inferiority complex when comparing herself to Taylor. (C) It’s almost something we can picture Alice doing herself.

As for A Place in the Sun, her role as Alice went entirely against her place in Hollywood, where she was being groomed as a sex symbol. When auditioning for the role, she dyed her hair brown and wore raggedy clothes to the point that Stevens didn’t even recognize her in his office. (C) The great irony is, of course, that Winters, who intentionally played against type, actually became typecast in that new image, even meeting the same watery fate in The Night of the Hunter (1955). Winters said that for years after the film, she drove around in white Cadillac convertibles, like that which Taylor drove in the film, as therapy for an inferiority complex when comparing herself to Taylor. (C) It’s almost something we can picture Alice doing herself.

![]()

A Tragic Love Affair

All of these characters are vivid, flawed and clearly motivated — just one reason the script took the Oscar. Another is it’s masterful lacing of themes of class. It’s there from the opening scene, where George stands overshadowed by an Eastman sign, and it continues with the subplot of the Vickers family being unsure George “belongs” in their upper-class crowd. Sure, George loves Angela, but a powerful driving decision in his scheme to off Alice is class. Killing her will not only allow him to be with Angela, it will provide an escape from his lower-class existence. To him, all is fair in love and class warfare.

Such social commentary was already there in Dreiser’s book, but since his novel spoke from a 1925 perspective, screenwriters Brown and Wilson had to consciously adapt the story to a ’50s audience. One of the chief strategies was to play up the romance, and play it up hard. (E) It was no easy task. The story had already flopped once as An American Tragedy (1931), thanks in part to director Sergei Eisenstein being fired on charges of “communism.” The fact that it was a familiar story hurts its originality, as does the boat scene, which mirrors Janet Gaynor in Sunrise (1927) and Gene Tierney in Leave Her to Heaven (1946). But duplication isn’t always bad, and the scene is the most suspenseful in the film.

Such scenes work best because they marry romance and fate to hatch tragedy. The tagline says it all: “Love that paid the severest of all penalties!” Brown and Wilson cleverly incorporate the forbidden romance into the dialogue, including Taylor’s gasping party statement, “Are they watching us?” and her last line to Clift: “Seems like we always spend the best part of our time, just saying goodbye.”

Like the best romances, these are star-crossed lovers, doomed to break apart in the end. Fate dictates it, as it does in Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, The Way We Were and Titanic, all of which make the AFI’s 100 Passions, where A Place in the Sun ranks No. 53.

Like the best romances, these are star-crossed lovers, doomed to break apart in the end. Fate dictates it, as it does in Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, The Way We Were and Titanic, all of which make the AFI’s 100 Passions, where A Place in the Sun ranks No. 53.

Here, the “hands of fate” belong to screenwriters Brown and Wilson, who know the outcome from the start and are smart enough to foreshadow it. Second-time viewers will realize the genius at work when Winters tells Clift, “When you’re an Eastman, you’re not in the same boat as anyone.”

Here, the “hands of fate” belong to screenwriters Brown and Wilson, who know the outcome from the start and are smart enough to foreshadow it. Second-time viewers will realize the genius at work when Winters tells Clift, “When you’re an Eastman, you’re not in the same boat as anyone.”

As much credit as Brown and Wilson deserve, it was actually Stevens who wrote the film’s most famous scene, the balcony kiss, the night before it was shot. The scene’s famous line, Taylor’s invitation to “Tell mama, tell mama all,” is something that would be deemed cheesy if it were said by an actress today, but looking back in a nostalgic, ’50s mindset, it works. Of course, there were those on set puzzled by the odd word choice, including Taylor.

“The little lady says, ‘Forgive me. Tell Mama. What the hell is this?’ I said, ‘This is what you’re going to say,'” Stevens said. “Elizabeth thought it was outrageous that she had to say that. Reasonable too — I am asking her to jump into a sophistication that is beyond her sophistication at the time. And also non-sequitor talk because it was spasmodic. I explained I’d like them to get it in their heads, rehearse it off-screen, then I would get them in there and throw them at one another. I tried to create the sense that this was primitive — the excitement of a preordained meeting where they find one another.” (C)

![]()

The Genius of George Stevens

“Preordained” is the key word. A Place in the Sun is the fine romance it is because of this idea of fate, and it is Stevens who twists that idea to the dark side. It was a side of Stevens audiences hadn’t seen before, developed after seeing the horrors of war as head of the U.S. Signal Corps Special Motion Picture Unit. His deputy from that unit, Ivan Moffat, was brought along as an associate producer on A Place in the Sun, and it was actually Moffat who came up with the title. (C) You can see the war’s influence on the water-skiing scene, where Stevens used recordings of German Stuka dive bombers to replace the sound of the speedboat engine. He wanted to make it more ominous. (A)

A Place in the Sun was Stevens’ second post-war picture, and it was without a doubt his darkest picture up to that point. It marked a departure from his pre-war work with Laurel and Hardy, the silly Alice Adams (1935), the adventurous Gunga Din (1939) and the romantic comedy Woman of the Year (1942). Yet with this darker side came his first of six nominations for Best Picture, and his first win for Best Director. He felt so strongly about every single frame that when NBC and Paramount cut the film up with commercials for TV, Stevens took both corporations to court. (C)

Which leads us to the all-important question: was Stevens a “great” director? He certainly made a ton of classics, but when you pry into elite academia, there’s a tendency to deride him as a safe, mainstream alternative to the true auteurs of his day. Rarely is he put in the same class as Hawks and Hitchcock.

Which leads us to the all-important question: was Stevens a “great” director? He certainly made a ton of classics, but when you pry into elite academia, there’s a tendency to deride him as a safe, mainstream alternative to the true auteurs of his day. Rarely is he put in the same class as Hawks and Hitchcock.

I, however, think George Stevens is one of the most underrated directors I’ve seen. A Place in the Sun may be his best-directed film for his uncanny ability to visually foreshadow events while completely manipulating his audience. In my book, that’s the mark of a good director.

![]()

Mise-En-Scene

The mise-en-scene here is just brilliant. The first thing that comes to mind is that neon “Vickers” sign, flashing in the background as George paces around his apartment. He need not say anything, because the sign tells us exactly what he’s thinking. Angela Vickers is on the brain.

Note also how the Eastman posters create an image of dual women in the background, symbolizing Clift’s affair.

Note how Angela’s car literally comes between Clift and Winters as they walk down the street.

Note how Angela’s car literally comes between Clift and Winters as they walk down the street.

There’s more clever mise-en-scene when George and Alice go to the D.A.’s office to get married, but can’t because it’s Labor Day (a pun in itself?). As they leave the courthouse, Stevens’ camera holds on a shot of the courtroom in clear foreshadowing.

There’s more clever mise-en-scene when George and Alice go to the D.A.’s office to get married, but can’t because it’s Labor Day (a pun in itself?). As they leave the courthouse, Stevens’ camera holds on a shot of the courtroom in clear foreshadowing.

The spiral gate between George and Angela suggests a swirling, Vertigo-like obsession similar to Billy Wilder’s use of swirling railings in Double Indemnity (1944).

The spiral gate between George and Angela suggests a swirling, Vertigo-like obsession similar to Billy Wilder’s use of swirling railings in Double Indemnity (1944).

This swirling obsession finally burst into flames as Taylor watches a newspaper clipping of Clift — and her relationship with him — burn in her fireplace.

![]()

Implied Sex of the Radio

My favorite touch may be the scene where George and Alice first make love, all in long-take. They start on a rainy porch and Clift comes inside to adjust the radio in the window sill.

Winters joins him inside and they dance in the shadows. Stevens’ camera slowly pushes forward, focusing in on the radio and forcing the actors off screen. With a smooth dissolve, night turns to day, the rain stops and a rooster crows.

Winters joins him inside and they dance in the shadows. Stevens’ camera slowly pushes forward, focusing in on the radio and forcing the actors off screen. With a smooth dissolve, night turns to day, the rain stops and a rooster crows.

As George exits, we cut to a whistle blowing. Ahh, sexual symbolism at its best. It was so much better when filmmakers had to find creative ways of expressing it, rather than vivid sex scenes. Hardcore nudity may be exciting, but it’s a creative cop out.

As George exits, we cut to a whistle blowing. Ahh, sexual symbolism at its best. It was so much better when filmmakers had to find creative ways of expressing it, rather than vivid sex scenes. Hardcore nudity may be exciting, but it’s a creative cop out.

The radio image returns later in the film, as George is spooked when a screaming woman is tossed into the water, reminding him of his plot to kill Alice. As the boat pulls away, you’ll see a pair of glasses sitting next to a radio, recalling the radio of the implied sex scene.

The radio image returns later in the film, as George is spooked when a screaming woman is tossed into the water, reminding him of his plot to kill Alice. As the boat pulls away, you’ll see a pair of glasses sitting next to a radio, recalling the radio of the implied sex scene.

![]()

Light, Dark, Soft, Close

But if you want to talk Stevens’ skill as director in this movie, you have to talk his mastery of light and dark. Working with favorite cinematographer William C. Mellor (Giant), Stevens chose to shoot in B&W because Technicolor, he said, had an “Oh what a beautiful morning” quality to it. (A) But the choice also allowed for better contrast between light and dark.

Early in the film, Stevens foreshadows the impending doom of George and Alice’s relationship by having them walk in and out of shadows on a suburban sidewalk. Note that George’s face is the one in darkness. David Lynch used a similar technique in Blue Velvet (1986).

When sitting in the car with Alice, discussing her pregnancy and thinking of killing her, his face is in complete darkness. Then, when he’s finally in the boat, debating whether to kill her, George’s face appears in half-light, half-dark, the two choices of his ethical dilemma.

The contrast also works to suggest the difference between Taylor and Winters. You’ll notice softer, lighter shots of Taylor, and darker, noir shots of Winters. The opposite lighting schemes tell the story itself. “What really interested me was the relationship of images, from this one to that. Shelley Winters busting at the seams with sloppy melted ice cream in a brass bed, against Elizabeth Taylor in a white gown with blue balloons floating from the sky. Automatically that’s an imbalance, and by imbalance you create drama.” (C)

The contrast also works to suggest the difference between Taylor and Winters. You’ll notice softer, lighter shots of Taylor, and darker, noir shots of Winters. The opposite lighting schemes tell the story itself. “What really interested me was the relationship of images, from this one to that. Shelley Winters busting at the seams with sloppy melted ice cream in a brass bed, against Elizabeth Taylor in a white gown with blue balloons floating from the sky. Automatically that’s an imbalance, and by imbalance you create drama.” (C)

How that juxtaposition of moods is handled is important. Stevens could have given Winters the lighter shots as the moral figure, and Taylor the darker shots as the extra-marital lover. But he plays it exactly the opposite, giving Winters the darker shots because this is how Eastman views her — a threat to his happiness, his “place in the sun.” In this way, we experience the film through Eastman’s eyes.

How that juxtaposition of moods is handled is important. Stevens could have given Winters the lighter shots as the moral figure, and Taylor the darker shots as the extra-marital lover. But he plays it exactly the opposite, giving Winters the darker shots because this is how Eastman views her — a threat to his happiness, his “place in the sun.” In this way, we experience the film through Eastman’s eyes.

“I wanted the audience to relate to a character whose behavior it might not subscribe to,” Stevens said. “To bring that about, one must let the audience see his desire. They have to know his need for the thing that, even accidentally, traps him. … I’m interested in knowing — as visually as it can be stated — what’s on the boy’s mind.” (C)

Helping us see what’s on his mind is Steven’s pioneering use of the extreme close-up. Case in point: the aforementioned balcony kiss scene. Not only do we get unorthodox over-the-shoulder shots, where Clift and Taylor’s shoulders block most of the frame, we also get multiple axial breaks, where the camera crosses an imaginary 180-degree line. Stevens certainly wasn’t the first to do it — see John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) — but it was still unorthodox, especially for such a mainstream director. Stevens addressed this very issue in an interview with Jim Silke of the AFI.

Helping us see what’s on his mind is Steven’s pioneering use of the extreme close-up. Case in point: the aforementioned balcony kiss scene. Not only do we get unorthodox over-the-shoulder shots, where Clift and Taylor’s shoulders block most of the frame, we also get multiple axial breaks, where the camera crosses an imaginary 180-degree line. Stevens certainly wasn’t the first to do it — see John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) — but it was still unorthodox, especially for such a mainstream director. Stevens addressed this very issue in an interview with Jim Silke of the AFI.

“You mean the cuts didn’t make orthodox cutting sense? I don’t mind doing that if it’s not disconcerting,” he said. “… I went from one side of the face to the other and created a tempo — as fast as the dialogue could be said, it was said. Monty had that kind of emotion that he got steamed up in it. And Liz is so dissolving when she is looking at you.” (C)

Which brings us to those beautiful soft-focus shots of her, which single-handled won Mellor the Oscar for cinematography. If Stevens won for Best Director, it was only fair, then, that Mellor win for Best Cinematography. That shot of Taylor’s face, covering the entire frame, is so soft that we melt into it. We can see Stevens’ obsession with the shot, as he superimposes it repeatedly for the remainder of the film, even ending on it as a superimposed memory of Clift’s mind.

Which brings us to those beautiful soft-focus shots of her, which single-handled won Mellor the Oscar for cinematography. If Stevens won for Best Director, it was only fair, then, that Mellor win for Best Cinematography. That shot of Taylor’s face, covering the entire frame, is so soft that we melt into it. We can see Stevens’ obsession with the shot, as he superimposes it repeatedly for the remainder of the film, even ending on it as a superimposed memory of Clift’s mind.

![]()

Waxman’s Music

By the time Taylor’s lips meet Clift’s, and Stevens fades to black, we get a strong dose of Franz Waxman’s strings. It was his ninth Oscar nomination, after beautiful scores for films like Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941). The Hitchcockian blend of suspense and romance was perfect for A Place in the Sun, which won Waxman his second Oscar in a row, after Sunset Blvd. (1950), which was ranked the AFI’s No. 16 greatest movie score.

The score for A Place in the Sun is heavy on the saxophone, and part of it was reused as diagetic sound in Rear Window, bringing Waxman full circle with Hitchcock and Raymond Burr.

The score works great in its original state, or conducted by modern conductors like the great John Williams. Listen around the 2:08 mark if you want to hear some beautiful movie music.

![]()

Legacy

Today, A Place in the Sun curiously holds just a 76% on rottentomatoes, despite making boat loads of other lists. The film made it onto the original AFI Top 100 (#92), but dropped off by the 10th Anniversary list. In fact, the AFI had a complete shake-up of its Stevens representation, dropping A Place in the Sun and Giant and adding Swing Time (1936), while keeping Shane, easily the best movie that Stevens made.

Will A Place in the Sun return the next time around? As folks reexamine the brilliant mise-en-scene laid out in this review, I hope that it will. But just because it dropped off this time around, doesn’t make it any less of a film. It’s one of those rare melodramas that doesn’t date. Rather, it boasts a sort of never-ending nostalgia. This one will live on, no matter how many times its story is retold. Ever seen Woody Allen’s Match Point?

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: IMDB Trivia

CITE B: Tim Dirks’ AMC Filmsite.org

CITE C: Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age: At the American Film Institute. George Stevens Jr.

CITE D: A Place in the Sun DVD Special Features

CITE E: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE F: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film