Director: Michael Curtiz

Producers: Jack Warner, Hal B. Wallis (Warner Bros.)

Writers: Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch (screenplay); Murray Burnett and Joan Alison (play)

Photography: Arthur Edeson

Music: Max Steiner

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains, Paul Heinreid, Conrad Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, Dooley Wilson, S.Z. Sakall, Madeleine Lebeau, Joy Page, John Qualen

![]()

Introduction

Watch most any Warner Bros. movie, from Blazing Saddles (1974) to The Shawshank Redemption (1994), and you’ll see a golden “WB” logo over nostalgic piano notes. These are the notes of “As Time Goes By,” the recurring theme from the film that has made Warner Bros. and all of Hollywood the most proud after 70 years.

Casablanca not only won Best Picture upon release, it remains the undisputed champion of Hollywood’s Golden Age and, according to film critic Leonard Maltin, “The best Hollywood movie of all time.” What a magnificent feat for a film that was just one of dozens cranked out by Warner Bros. in 1942, and one of three shot by Warner director Michael Curtiz that year.

Amid the height of this studio assembly line, somehow all the stars aligned — a powerful cast, an “exotic” soundstage locale, one of the great love songs in music history, the best script ever written, and current-events subject matter pitting romance against the Nazi attempt to take over the world.

As you’d expect from a film based on a play, Casablanca takes place largely in one location with much of the plot executed through conversation. Thus, in order to fully appreciate the film, you must actually listen to the dialogue. This may be a tall order for a generation raised on special effects, but we owe Casablanca that much. After all, it goes out of its way to layer its profundity with entertaining plot twists, romance, gunfire and double crosses. For this reason, it remains a true titan on both ends of The Film Spectrum, cheered by both the public (8.7 IMDb) and the experts (#3 AFI Top 100).

“Casablanca is a triumph of the filmmaking process,” said director William Friedkin (The French Connection, The Exorcist). “It’s like what makes a good meal. A great chef, of course, but (it’s) the ingredients. The ingredients have to be perfection. In this case, they are.”

![]()

Plot Summary

It’s December 1941 and the Nazis have occupied much of Europe, joining with the Italian Vichy in North Africa to hold close watch over the city of Casablanca in French Morocco. Here, tons of European refugees have fled in hopes of obtaining exit visas and heading to Lisbon, the embarkation point to America. Under Nazi control, these visas are hard to come by, turning Casablanca into a melting pot of nationalities, breeding both opportunistic entrepreneurs and con-men ready to pounce.

Among the former is Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart), a hardened American expatriate operating Rick’s Cafe Americain, and carrying plenty of scars from the past. Suspected as a place where underground French resistence fighters conduct their covert business, Rick’s is under constant Nazi/Vichy supervision, namely that of Third Reich enforcer Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt) and the endearing police chief Renault (Claude Rains). Rick vows to stay above the fray, “sticking his neck out for nobody,” but can no longer help it when Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), the woman who broke his heart years ago in Paris, arrives for a drink.

At her side is husband Victor Laszlo (Paul Heinreid), a famous and respected resistance leader who comes to Rick for help. It seems Rick has stumbled across two very important letters of transit that would enable Victor and Ilsa to fly out of Nazi territory and continue the Allied cause from the Western Hemisphere. But there is one major variable — the passionate past between Rick and Ilsa. In the end, Rick and Ilsa are left with a heart-wrenching decision: to pursue the desires of their hearts or the well-being of all mankind.

![]()

History’s Greatest Script

Voted by the Writers Guilds as the single greatest screenplay of all time, Casablanca continues to wow aspiring screenwriters for its precision amidst chaos. In 1940, playwright Murray Burnett teamed with Joan Alison to write the play Everybody Comes to Rick’s, which never made it to the stage. The script sat for a year in the office of Jack Wilk, story editor for Warner East Coast operations in New York, until it was discovered by Irene Lee, head of the Warner Bros. story department. Warner Brothers purchased the play for $20,000, the most anyone had ever paid for an unproduced work. (A) (C)

The Oscar-winning script began as anything but, written by three screenwriters in separate locations in a down-to-the-wire crunch. Julius J. and Philip G. Epstein were twin brothers with separate Hollywood writing careers until they became a team in 1938. Meanwhile, Howard Koch had written the infamous “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast for Orson Welles. The Epsteins did not finish their script until three days before the shoot, while Koch did not complete his until two weeks after shooting began. The two separate writing parties never even worked in the same room.

Considering all of this, one has to wonder what divine inspiration or cosmic fate graced these pages, because despite the hectic nature of its creation, it somehow crackles with dialogue, holds the weight of high stakes, dances along a riveting plot and charts the most complex of characters.

Dialogue. Six quotes, count ’em, six, made the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes, doubling its closest competition (Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz) and sextupling almost every other movie on the list. Think about that for a second. Each screenwriter hopes to pen one line that’s remembered for all time. These guys wrote six in the same script and four in the final minutes! As Jennifer Grey remarked to the AFI, “What were these writers having for breakfast?” Here they are in ranked order:

(#67) “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.” The classic line acknowledges fate’s cruel hand and sets up the idea of star-crossed lovers.

(#43) “We’ll always have Paris.” These four words have become shorthand for remembering the good times of lovers past.

(#32) “Round up the usual suspects.” Not only did it inspire the title of The Usual Suspects (1995), it served as arguably the greatest heel-to-babyface turn in movie history. How did it come about? “The true story is that while driving down Sunset Boulevard, the twins came to the red light at Beverly Glen,” said Leslie Epstein, of her screenwriter father Philip and uncle Julius. “While they were waiting, they turned to each other and with one voice cried out, ‘Round up the usual suspects!’” (C)

(#28) “Play it, Sam.” The line is often misquoted as “Play it again, Sam,” thanks to a quote by Groucho Marx in the spoof comedy A Night in Casablanca (1946) and the title of Woody Allen’s Play it Again, Sam (1972), where he envisions Bogart as his imaginary friend who provides dating advice.

(#20) “Louie, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” Following Rains’ babyface turn with the “usual suspects” line, this line by Bogart seals the deal. In When Harry Met Sally (1989), Billy Crystal calls it the “best last line in a movie ever.”

(#5) “Here’s looking at you, kid.” Perhaps the coolest movie quote in all of history, millions have probably quoted it without even knowing where they heard it. Now that’s a great movie quote. Ironically, it was improvised by Humphrey Bogart in the flashback Parisian scenes and worked so well that it was used repeatedly throughout the film as a “pet name” between the two lovers. (A) It went on to top Premiere magazine’s 2007 list of the 100 Greatest Movie Lines of All Time.

The film also features other superb lines that didn’t make the AFI list, like “I stick my neck out for nobody,” which was voted #42 on Premiere’s 100 Greatest Movie Lines. The entire script drips with sass (“I remember every detail, the Germans wore gray, you wore blue”), delicious melodrama (“Was that cannon fire or is it my heart pounding?”) and biting comedic reversals (“I’m shocked to find that gambling is going on in here,” followed by “Your winnings, sir”). As Julius Epstein said, “It doesn’t matter how serious a film is … the right kinds of laughs can work in any film!” (C)

Highest of Stakes. Of course, the events surrounding the film were no laughing matter. The original play arrived at Warner Bros. Studios to be read as a potential film project the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. (A) Thus the poignancy of Bogart’s line, “It’s December, 1941 in Casablanca. What time is it in New York? I bet they’re asleep in New York. I bet they’re asleep all over America.”

The weight of the war hovered over the film. The Epsteins remained on call throughout the shoot, despite having moved to Washington to work on Frank Capra’s Why We Fight documentary series. (C) When President FDR returned from a wartime conference in Casablanca with Winston Churchill, he asked for a screening of the film at the White House, which in Spanish reads “casa blanca.” (A)

The film’s anti-Nazi message was very personal to the cast, many of whom were German Jewish refugees themselves, gathered in this melting pot of this “exotic” Warner Bros. studio lot. (A) The film’s win for Best Picture was Hollywood’s statement that democratic values would triumph over Hitler’s oppression. With this in mind, the film’s famous battle of national anthems transcends the screen, becoming one of the most powerful scenes ever committed to film.

Plot of Uncertain Outcomes. Seeing as the film was released in late 1942, and the war ended in 1945, the outcome remained uncertain. Viewers had to entertain the possibility that the Axis Powers could actually win, that much of Hollywood could be sent to Hitler’s concentration camps, and that Casablanca and every other Hollywood film would be erased from history.

Just as world history was still unwritten, so was the film’s script. The screenwriters rewrote the pages all along the way, staying just a few days ahead of the shoot. Rick’s line is no coincidence: “Does it got a wild finish? Well go on and tell it, maybe one will come to you as you go along.” This is part of the film’s allure — the feeling that things could go either way.

“Warner had 75 writers under contract, and 75 of them tried to figure out an ending,” Julius Epstein said. (C) In fact, debates over the film’s ending carried on so long that Bergman had no idea until the very last minute whether her character would end up on the plane with Victor or Rick. “The ending of the film was in the air until the very end,” said Koch. “… Ingrid Bergman came to me and said, ‘Which man should I love more…?’ I said to her, ‘I don’t know… play them both evenly.’ You see we didn’t have an ending, so we didn’t know what was going to happen!” (C)

Complex Characters. This uncertainty would have not have worked if the film had not rendered such complex characters into such complex situations. Roger Ebert wrote, “After seeing this film many times, I think I finally understand why I love it so much. … It’s because it makes me proud of the characters. These are not heroes — not except for Paul Heinreid’s resistance fighter, who in some ways is the most predictable character in the film. These are realists, pragmatists, survivors … when they rise to heroism, it is so moving because heroism is not in their makeup. Their better nature simply informs them what they must do.”

Thus Rick Blaine’s place as the AFI’s #4 Hero of All Time, behind only Atticus Finch (#1), Indiana Jones (#2) and James Bond (#3). Note that those three are larger than life figures, while Rick goes through the greatest growth. He journeys from romantic to guarded and back again. At the start of the film, he sticks his neck out for no one. By the end, he believes anything is possible and that he’s the one that can make it possible.

I once had the privilege to hear a guest lecture by famed Hollywood script doctor Dara Marks, author of Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Her analysis of Rick Blaine went something like this: “The story is about how a man whose heart has been so hurt in the past that he shuts others out, but he changes to do something for the greater good and becomes connected with the rest of the human race. He’s alive again. Before, he might as well have been a living corpse.”

It’s imperative that we note the difference between the Rick in the Paris flashbacks, where he is in love and alive, and the Rick left running the nightclub in Casablanca, where he’s no more than a jaded, world-weary cynic. The reason for his transformation is obvious — a broken heart. Note that in the Paris flashbacks, he suggests to Ilsa that they get married, only for her to say, “That’s too far ahead to plan.” Then, after his emotional devastation, he turns to the very same language in the bar. It’s Ilsa that warped him, and the journey back will require her. The moment he tells another young lover to “play #22” in roulette is the first sign of Rick’s return to romanticism.

Renault senses this all along. Rick asks, “Louie, what ever gave you the impression that I might be interested in helping Laszlo escape?” Renault replies, “Because, my dear Rickie, I suspect that under that cynical shell, you are at heart a sentimentalist.” He mentions that Rick once ran guns to Ethiopia to help the natives fend off Italy’s invasion in 1935.

![]()

Bogie and Bergie

In 1941, studio publicity claimed that Ronald Reagan and Ann Sheridan were scheduled to appear in this film, and Dennis Morgan was mentioned as the third lead. This was never the case, however, as the false story was planted, either by a studio publicist or a press agent, to keep the actors’ names in the press. Meanwhile, George Raft (Scarface) asked Jack L. Warner to give him the part, but it was Hal B. Wallis who was assigned to search for the part of Rick.

Wallis wrote to Warner saying he felt the role was perfect for Humphrey Bogart. There was just one stipulation: Wallis didn’t want Bogie wearing a hat too often, as he thought it made him look like a gangster. (A) After all, Curtiz had put Bogart on the map four years earlier as a gangster in Angels With Dirty Faces (1938), before launching to stardom as Detective Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1941).

Casablanca earned Bogie his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor, somehow losing to Paul Lukas for Watch on the Rhine (1943). If not his best performance (probably The Treasure of the Sierra Madre), it’s certainly his career role, the one for which he’s remembered. After all, Bogart alone has four quotes on the AFI’s 100 Movie Quotes, more than most others have in an entire career. The film was the 45th in his career, but his first as a romantic lead, an experiment that struck gold.

Casablanca earned Bogie his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor, somehow losing to Paul Lukas for Watch on the Rhine (1943). If not his best performance (probably The Treasure of the Sierra Madre), it’s certainly his career role, the one for which he’s remembered. After all, Bogart alone has four quotes on the AFI’s 100 Movie Quotes, more than most others have in an entire career. The film was the 45th in his career, but his first as a romantic lead, an experiment that struck gold.

“How can a man so ugly be so handsome?” asked Marta Toren in Sirocco, wondering how this hardboiled, on-screen ass could have so much damn appeal. The women are drawn to him and the men want to be him, and Casablanca is a prime example. “I didn’t do anything I’ve never done before,” Bogart said, “but when the camera moves in on that Bergman face, and she’s saying she loves you, it would make anybody feel romantic.” (A)

Today, it’s hard to imagine anyone else as Isla, but the role was first offered to Michèle Morgan, who held out for $55,000. Wallis refused to pay it when he could get Ingrid Bergman for $25,000. (A) He also considered Hedy Lamar, but once he decided the character would be European, he went straight for Swedish-native Bergman, who was brought to Hollywood three years earlier by David O. Selznick, who loaned her out more than he used her. (B)

It was Casablanca that  made her a star, such that in The Godfather (1972) Diane Keaton asks Al Pacino as they exit Radio City Music Hall, “Would you like me better if I were Ingrid Bergman?” In one of those head-scratching moments of movie history, Bergman wasn’t even nominated for Casablanca, but it catapulted her to seven future nominations, winning three times over a 30-year span for Gaslight (1944), Anastasia (1956) and Murder on the Orient Express (1974).

made her a star, such that in The Godfather (1972) Diane Keaton asks Al Pacino as they exit Radio City Music Hall, “Would you like me better if I were Ingrid Bergman?” In one of those head-scratching moments of movie history, Bergman wasn’t even nominated for Casablanca, but it catapulted her to seven future nominations, winning three times over a 30-year span for Gaslight (1944), Anastasia (1956) and Murder on the Orient Express (1974).

Still, we’ll always remember her in Casablanca, vulnerable yet brave, totally believable with each tear shed, and awestruck with a pride-filled face watching Victor leading the band in a rousing rendition of “La Marseilleise,” reminding her why she loves him in the first place.

Ironically, it was the only film where Bogie and Bergie appeared together, as Bogart fell for co-star Lauren Bacall two years later in To Have and Have Not (1944) and Bergman fell for director Roberto Rossellini and moved to Italy. While the paths of their off-screen hearts diverted, Bogie and Bergie will “always have Paris” in the hearts of movie lovers.

![]()

Supporting Cast

The reason Bogie and Bergman work so  well are the string of performances around them. As the third wheel of the love triangle, Paul Heinreid was the perfect fit for Victo Laszlo, having appeared in both the Bette Davis romance Now, Voyager (1942) and Carol Reed’s war thriller Night Train to Munich (1940), about the Germans marching into Prague. Henreid was loaned to the Warners by Selznick International Pictures against his will, because he was concerned that playing a secondary character would ruin his career as a romantic lead. (A)

well are the string of performances around them. As the third wheel of the love triangle, Paul Heinreid was the perfect fit for Victo Laszlo, having appeared in both the Bette Davis romance Now, Voyager (1942) and Carol Reed’s war thriller Night Train to Munich (1940), about the Germans marching into Prague. Henreid was loaned to the Warners by Selznick International Pictures against his will, because he was concerned that playing a secondary character would ruin his career as a romantic lead. (A)

Heinred’s Now, Voyager co-star Claude Rains steals the Casablanca show, giving a pragmatic performance somewhere between good and evil, as he later would in Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), where he again plays a Nazi henchman. In Casablanca, his Captain Louis Renault drives the film’s attitude, a blend of danger and humor on a journey from practical to moral. The role earned Rains his second of four Oscar nominations, sandwiched between Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Mr. Skeffington (1944). He lost to his King’s Row (1942) co-star Charles Coburn, who won for The More The Merrier (1942). Sadly, Rains never took home the statue, but if there were one performance where he should have won, this was it.

Heinred’s Now, Voyager co-star Claude Rains steals the Casablanca show, giving a pragmatic performance somewhere between good and evil, as he later would in Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), where he again plays a Nazi henchman. In Casablanca, his Captain Louis Renault drives the film’s attitude, a blend of danger and humor on a journey from practical to moral. The role earned Rains his second of four Oscar nominations, sandwiched between Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Mr. Skeffington (1944). He lost to his King’s Row (1942) co-star Charles Coburn, who won for The More The Merrier (1942). Sadly, Rains never took home the statue, but if there were one performance where he should have won, this was it.

For the role of Renault’s superior, Major Strasser, Curtiz went with Conrad Veidt, who had played the somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). On loan from MGM with a salary of $25,000 for five weeks of work, Veidt was the highest-paid actor on set. His main competition for the role was Otto Preminger, under contract with 20th Century Fox, but Darryl F. Zanuck demanded the outrageous sum of $7,000 per week. Veidt’s casting was ironic, as he was known in German theater for his hatred of the Nazis, such that he was forced to flee the country after the SS sent a death squad after him. Veidt became typecast in the role of Nazi villains, but he was convinced his “bad guys” would help the war effort against Hitler.

For the role of Renault’s superior, Major Strasser, Curtiz went with Conrad Veidt, who had played the somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). On loan from MGM with a salary of $25,000 for five weeks of work, Veidt was the highest-paid actor on set. His main competition for the role was Otto Preminger, under contract with 20th Century Fox, but Darryl F. Zanuck demanded the outrageous sum of $7,000 per week. Veidt’s casting was ironic, as he was known in German theater for his hatred of the Nazis, such that he was forced to flee the country after the SS sent a death squad after him. Veidt became typecast in the role of Nazi villains, but he was convinced his “bad guys” would help the war effort against Hitler.

Bogart was also backed by his buddies Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet, who had just played his nemeses Joel Cairo and Kasper Gutman in The Maltese Falcon (1941). Perhaps the name “Cairo” was foreshadowing to Casablanca‘s North African setting. While Lorre’s career role was the serial child molester in Fritz Lang’s German masterpiece M (1931), his Ugarte character is crucial to Casablanca as the one who drops off the exit visas,

Bogart was also backed by his buddies Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet, who had just played his nemeses Joel Cairo and Kasper Gutman in The Maltese Falcon (1941). Perhaps the name “Cairo” was foreshadowing to Casablanca‘s North African setting. While Lorre’s career role was the serial child molester in Fritz Lang’s German masterpiece M (1931), his Ugarte character is crucial to Casablanca as the one who drops off the exit visas, coveted by Greenstreet’s Ferrari.

coveted by Greenstreet’s Ferrari.

Rounding out the cast is the lovable Dooley Wilson as Rick’s cafe piano man Sam. Producer Hal B. Wallis nearly made the character Sam a female, considering Hazel Scott, Lena Horne and Ella Fitzgerald for the role. Instead, Wilson was borrowed from Paramount at $500 a week, and what a find. (A) Wilson tells viewers a world of information simply with his honest face and silky smooth voice.

![]()

Play it, Sam

The music in Casablanca is second to none. Wilson kicks things off with “It Had to Be You,” a song that became a pop hit for Harry Connick Jr. in the Casablanca-worshiping When Harry Met Sally (1989). From there, he plays familiar tunes like “Babyface” and “You Must’ve Been a Beautiful Baby.”

The home run comes with the incomparable “As Time Goes By,” a song of nostalgic lost love with which everyone can relate. We’ve all had that song once shared with a past lover whose memory comes roaring back the minute we hear it. For Rick and Ilsa, that song is “As Time Goes By.” After a run of memorable covers, from Frank Sinatra to Barbara Streisand, the song was voted all the way to No. 2 on the AFI’s 100 Movie Songs, behind only Judy Garland’s “Over the Rainbow.”

Not only is the song sung beautifully by Wilson, bringing tears to Ilsa’s eyes, it also reappears throughout Max Steiner’s musical score, which kicks off with the Warner Bros. suite before diving into exotic percussion and patriotic fervor. Casablanca earned Steiner his 11th Oscar nomination, having won previously for The Informer (1935) and Now, Voyager (1942), starring Heinreid and Rains.

![]()

Visuals

If the music makes Casablanca, its visuals solidify the atmosphere. The opening street bazaar scenes were filmed on the same studio backlot of The Desert Song (1943), which earned an Oscar nomination for Art Direction. In Casablanca‘s market scene, where one of the Resistance members is shot, you’ll notice a wall painted with a picture of Marshal Pétain and a quote, which translated into English, reads, “I keep my promises, even those of other people.” Plenty of other people swarm this marketplace, a melting pot of various nationalities who are supposedly stuck in Casablanca waiting for exit visas. Warner Brothers claimed that people of 34 nationalities worked on the film. (A)

While these Moroccan streets come to mind when we think Casablanca, most of the film unfolds from within the confines of Rick’s Café Américain, modeled after the Hotel El Minzah in Tangiers. Rick’s Cafe was one of the few original sets built for the film, while the rest were recycled from other Warner Bros. productions due to wartime restrictions on building supplies (i.e. the Paris train station was recycled from Now, Voyager). (A)

While these Moroccan streets come to mind when we think Casablanca, most of the film unfolds from within the confines of Rick’s Café Américain, modeled after the Hotel El Minzah in Tangiers. Rick’s Cafe was one of the few original sets built for the film, while the rest were recycled from other Warner Bros. productions due to wartime restrictions on building supplies (i.e. the Paris train station was recycled from Now, Voyager). (A)

World War II also affected the location of the film’s finale, filmmakers were not allowed to film at any airport after dark for security reasons. Instead, they used a soundstage and a small cardboard cutout of an airplane. To give the illusion that the plane was full-sized, Curtiz used little people to portray the crew preparing the plane for take-off. (A)

World War II also affected the location of the film’s finale, filmmakers were not allowed to film at any airport after dark for security reasons. Instead, they used a soundstage and a small cardboard cutout of an airplane. To give the illusion that the plane was full-sized, Curtiz used little people to portray the crew preparing the plane for take-off. (A)

![]()

Curtiz the Chameleon

With all of these “ingredients,” Warner Bros. needed to find an able chef. Hal B. Wallis originally wanted William Wyler, who was fresh off a Best Director win for the war flick Mrs. Miniver (1942). The studio was also considering Howard Hawks, who claims he was supposed to direct Casablanca and Michael Curtiz was supposed to direct Sergeant York (1941). When the directors got together for lunch, Hawks said he didn’t know how to make this “musical comedy,” while Curtiz didn’t know anything about “those hill people,” so they switched projects. (A) Ironically, Hawks would recreate Dooley Wilson’s piano scene with Hoagy Carmichael and Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not (1944).

Obviously, the switch worked out well for Curtiz, who finally won Best Director after losing four times for Captain Blood (1935), Four Daughters (1938), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) and Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942). Despite the win, Curtiz will never go down as one of history’s great visionary directors, as his biggest strength was being economical rather than artistic. Steven Spielberg once compared himself to Curtiz, explaining how they are both good at playing audiences’ emotions and tackling an array of genres, but aren’t necessarily auteurs like Hitchcock, Welles or Scorsese.

Even so, Curtiz deserves credit for a few directorial techniques:

Visual Rhymes

Curtiz is smart enough to know our subconscious affection for visual rhymes. Note his use of parallelism throughout the film, like Bergie and Bogie both knocking over glasses in different scenes.

Shadows

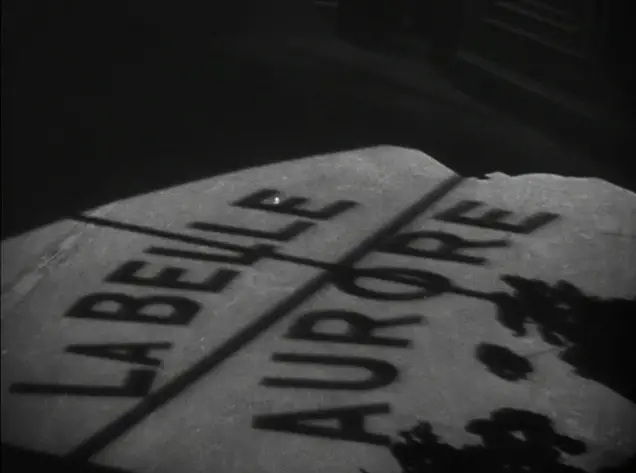

Curtiz also makes clever use of shadows, pulling from the noir influences of the decade. Many of the film’s shadows were reportedly painted onto the set in an artistic blitzkrieg of the very German Expressionism that Veidt brought with him from Caligari. (A) Painting with actual light and shadow is Oscar-nominated cinematographer Arthur Edeson, fresh off All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Frankenstein (1931) and The Maltese Falcon (1941), which showed a similar Spade/Archer shadow on the floor as the one cast by the La Bell Aurore window in Casablanca.

The film’s most important shadow comes when Rick opens a wall safe. The way Bogart’s body is positioned makes Rick appear to be the shadow of Capt. Renault, a symbolic statement that the morals of these two men might be one in the same, “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

The film’s most important shadow comes when Rick opens a wall safe. The way Bogart’s body is positioned makes Rick appear to be the shadow of Capt. Renault, a symbolic statement that the morals of these two men might be one in the same, “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Mirrors

Mirrors

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire, and where there are shadows in movies, there are usually mirrors. In Casablanca, Curtiz uses mirror reflections for both style and meaning. For style, Rick is shown coming downstairs to the cafe in a bar mirror.

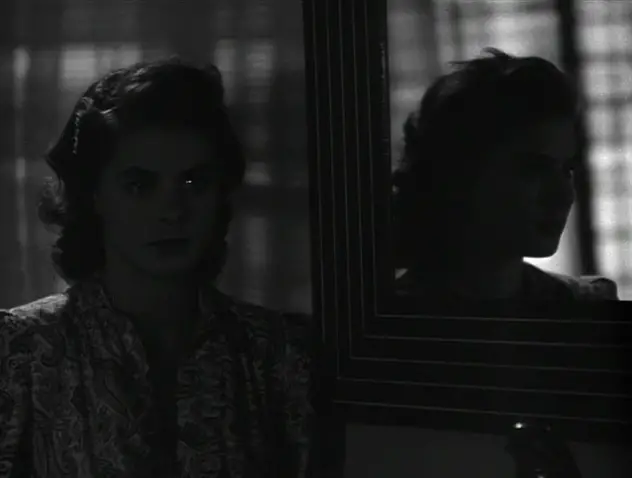

For meaning, Ilsa’s reflection appears at a time when there are literally two sides of her, each in love with a different man.

For meaning, Ilsa’s reflection appears at a time when there are literally two sides of her, each in love with a different man.

Working the Space

Curtiz also succeeds in turning Rick’s Cafe into a three-dimensional space, beginning many scenes looking through windows or between posts. This visually suggests that the world exists independently of the characters, that fate is predetermined, accenting Rick’s notion that “the lives of three people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.”

![]()

Pop Culture

Even if you’ve never seen Casablanca, you’ve almost certainly seen its influences. The pop culture references began less than two years later when To Have and Have Not (1944) featured an almost identical plot, where Bogart plays an expatriate American helping to transport a Free French Resistance leader and his beautiful wife, while rubbing elbows with a nightclub singer.

The Marx Brothers did a hilarious send-up of the movie in A Night in Casablanca (1946), where Groucho sparked decades of misquoted confusion by saying, “Play it again, Sam.”

In Billy Wilder’s classic romantic comedy Sabrina (1954), Humphrey Bogart’s character has a painful memory of a woman in Paris, an homage to Rick’s painful Paris memories of Isla. Five years later in Alain Resnais’ masterpiece Hiroshima mon Amour (1959), the nightclub visited by Lui and Elle is called (without accident) Casablance. Bugs Bunny and company also spoofed it in “Carrot Blanca.”

In Diamonds are Forever (1971), Tiffany Case’s line while in bed with James Bond for the first time: “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful relationship.” Woody Allen references it in Play it Again, Sam (1972), where his character has Bogart as an imaginary friend lending advice on dating, and where he recreates Casablanca‘s runway scene with Diane Keaton. Allen was a huge Casablanca fan, having Isaac tell Tracy, “We’ll always have Paris” in Manhattan (1979).

The 1973 Best Picture The Sting (1973) features a rigged Black 22 at the roulette wheel, where Hooker loses the bet at the beginning of the movie. Black 22 is, of course, the same spot that Rick uses to let a desperate Albanian couple win. In When Harry Met Sally (1989), Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan watch Casablanca in split screen, calling the film’s final line the “best last line in a movie ever.”

Children’s TV shows offered their own parodies, from Sesame Street to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

The most famous cartoon spoof may have come when The Simpsons spoofed the film’s “up in the air” ending.

The film’s impact has even carried over into today’s music world, most notably in the Fall Out Boy song, “Of all the Gin Joints in All the World.”

![]()

Legacy

It’s hard to imagine an American best list that doesn’t include Casablanca near the top. Somehow it wasn’t included in the latest Sight & Sound Top 50, a list that prefers directorial vision over script, which to me, means it’s missing a huge part of the equation. And so, Sight & Sound will remain the odd man out, while Leonard Maltin calls it the Best Hollywood Movie Ever Made, while the Writers Guild of America votes it the Greatest Screenplay of All Time, and while the American Film Institute calls the Greatest Romance of All Time.

Film scholar David Thomson called it “a women’s picture for men.” (B) There truly is something for everybody here, which is why the film ranks so highly on so many different AFI lists, across Thrills, Cheers and Passions. “Everybody holds it out as the benchmark of great love stories,” said the late director Sidney Pollack, whose lovers ultimately split in The Way We Were (1973). “Great love stories have sacrifice in them. Great love stories have people who can’t end up together.”

This realization hits during the film’s famous finale, where Bogie articulates the key to the entire movie: “Ilsa, I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Someday you’ll understand that.”

This realization hits during the film’s famous finale, where Bogie articulates the key to the entire movie: “Ilsa, I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Someday you’ll understand that.”

Turns out, Casablanca is good at being noble. Excellent at it. To we the viewers, the problems of these three little people amount to a whole heck of a lot. A gigantic hill of beans. They are not superheroes with super powers, but ordinary people doing extraordinary things when the stakes couldn’t be any higher. That is the true definition of heroism, when fate, love and duty collide into action.

Today’s viewers may need a quick refresher on Nazi influence in Vichy France. They may also need to overlook the datedness of the opening narration over a spinning globe. But the film’s timeless truths will endure. As long as there are sentimentalists, there will be a place for Casablanca. It will live on forever. We’ll play it again and again, Sam. No matter how much time passes, “It’s still the same old story, a fight for love and glory, a case of do or die. The world will always welcome lovers, as time goes by.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: IMDB Trivia

CITE B: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE C: WGA Top 101 Screenplays Facts