Director: Roman Polanski

Producer: Robert Evans (Paramount)

Writer: Robert Towne (screenplay)

Photography: John A. Alonzo

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston, Perry Lopez, John Hillerman, Diane Ladd, Roy Jensen, Burt Young, Roman Polanski, Bruce Glover, James Hong

![]()

Introduction

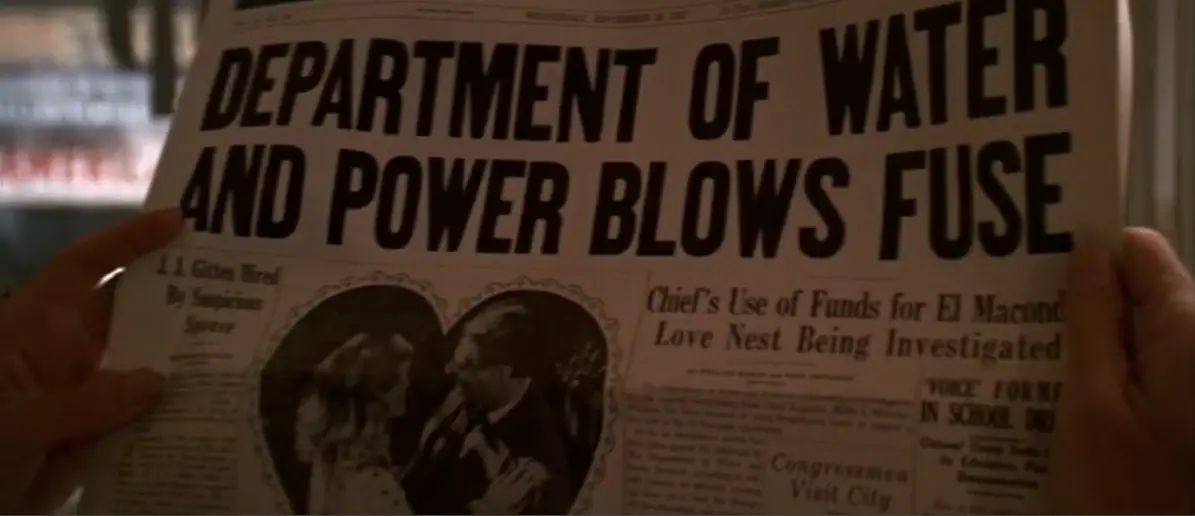

“In the middle of a drought and the water commissioner drowns! Only in L.A.”

Movies don’t get much better, or better written, than Chinatown. Roman Polanski’s masterpiece joined Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) in reviving the Hollywood detective story for the next 25 years, bringing films like Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Dick Tracy (1990), L.A. Confidential (1997) and the Chinatown sequel The Two Jakes (1990).

This “neo noir” trend resurrected a genre that was left for dead after a stretch from 1941-1958, bringing us masterpieces like The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity, Laura, The Big Sleep, Out of the Past and Touch of Evil. Back were the the private dicks, femme fatales, venetian blinds and smoky silhouettes, but they were now infused with a modern style reflecting the corruption of the modern age.

If you like happy endings where the good guys triumph and the bad guys get their comeuppance, don’t enter Chinatown. But if you like the hand of fate leading twisted folks to tragic conclusions, Chinatown will snip your nose and wash you away. The film dominated the Golden Globes, winning Best Picture, Actor (Jack Nicholson), Director (Polanski) and Screenplay (Robert Towne), and it would have repeated at the Oscars if it weren’t for The Godfather: Part II (1974). Instead, the film’s only Oscar went to Towne’s script, which peels back its layers like a ripe onion voted the AFI’s No. 2 Mystery of All Time, behind only Vertigo (1958).

![]()

Plot Summary

It’s 1940s Los Angeles and Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) knows how to get dirt on just about anyone. Since quitting the police force after a traumatic experience in Chinatown, Jake has set up shop as a private detective, his latest contractor being a Mrs. Evelyn Mulwray (Diane Ladd) who wants him to investigate her two-timing husband, Hollis Mulwray (Darrell Zwerling), head of L.A. Water and Power.

The investigation flips when the real Mrs. Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) shows up pissed that she’s been impersonated and that her husband has been smeared. A romantic relationship ensues, but a number of questions remain. Who was this other woman? Why would she want to set up Mr. Mulwray? And what does it have to do with the fishy, freak appearances of runoff water that Gittes has noticed amid the city’s drought?

All of these questions are slowly answered as Jake digs deeper into the ranks of Water and Power, the orange groves of the Northwest Valley, the Albacorp dealings of a wealthy land magnate and the dark secrets of a truth-bending lover, culminating in a most haunting return to Jake’s least desired neighborhood — Chinatown.

![]()

Screenplay

How is it that a script this complex can did not from a novel, but rather from the mind of a single screenwriter? Robert Towne knew the city like the back of his writer’s hand. A native of Southern California, he conducted extensive research into the city’s secret histor, turning the into a love note to Los Angeles and an indictment of its corrupt history. (A) The story is inspired in part by the Watergate scandal (Nixon resigned two months after Chinatown hit theaters) and the 1908 “Rape of Owens/San Fernando Valley” in a water-stealing scandal. (B) Thus the film’s villain is fittingly named Noah Cross after the Biblical flood, in this case a flood of literal and symbolic rape that sweeps Nicholson away in rushing water, pinning him up against his own water gate.

Plot. Voted the WGA’s No. 3 Greatest Screenplay of All Time, the mystery unfolds like a thinking-man’s flick, packed with plot twists and detective tricks (i.e. the clever use of a pocket watch) that keep you guessing. Scholar David Thomson calls it “the last of the great complicated story lines that movies dared,” (A) and screenwriter Blake Snyder said, “It’s one of those movies that you can see a thousand times and drive deeper into smaller and smaller rooms of the Nautilus shell with each viewing.” (C) In the end, we’re left with an entirely different picture than we ever imagined at the start. Noah Cross articulates this very sentiment: “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t.”

SPOILER: The line is an allusion to one of the sickest twists in movie history. As Jake slaps Evelyn and says, “I want the truth,” Evelyn might as well snap back with Nicholson’s quote from A Few Good Men (1992): “You can’t handle the truth!” From this moment on, the film enters a new context, ensuring a second viewing experience that’s completely unique from the first, from the opening row-boat scene, to Jake’s first conversation with Noah, to Jake’s post-sex convo with Evelyn.

Dialogue. Equally fascinating on repeat viewings is the bite of snappy dialogue, putting Jake Gittes on par with Bogie’s best as Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe. It kicks off with Jake’s first line to Burt Young: “You don’t have to eat the venetian blinds, Curly. I just had them installed on Wednesday.” It continues with killer put-downs (“You’re dumber than you think I think you are”), ironic quips (“Well, to tell you the truth, I lied a little”), clever analogies (“Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough”) and the AFI’s No. 74 Greatest Move Quote of All Time: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

The script is most on fire in exchanges between characters. When a cop asks, “Isn’t that your phone number?”, Jake responds, “Is it? I forget. I don’t call myself that often.” When a woman asks, “Are you alone?” Jake replies, “Isn’t everybody?” Still, the best exchange comes between Jake and Evelyn: “It seems like half the city is trying to cover it all up, which is fine by me. But Mrs. Mulwray, I god-damned near lost my nose. And I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think that you’re hiding something.”

![]()

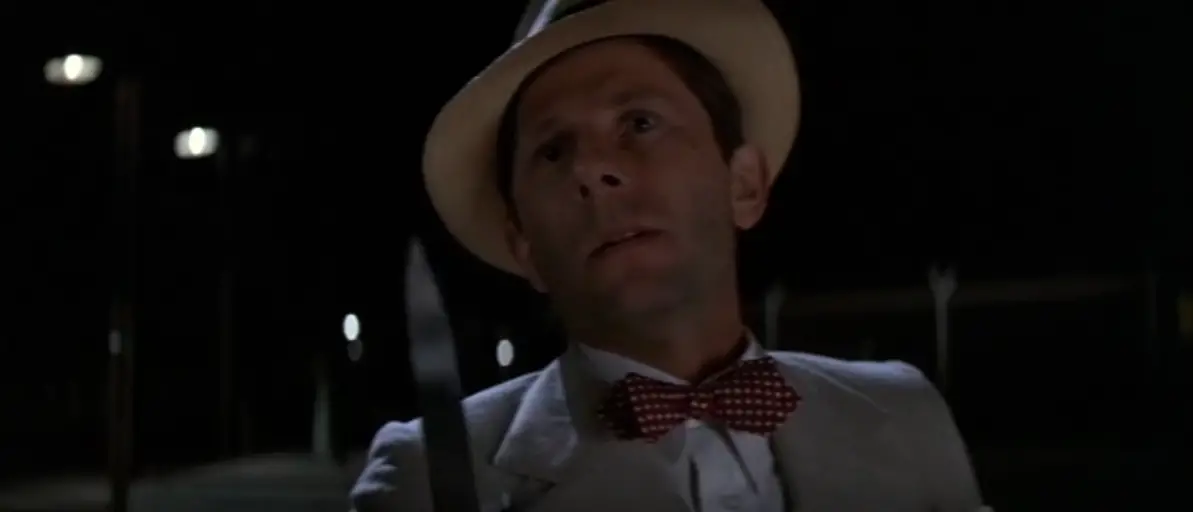

Jack Nicholson: Bandaged Hero

If the lines seem tailor-made for Nicholson, it’s because they are. Towne wrote the entire script for his good friend Nicholson, who contributed heavily to his own dialogue. After bursting on the scene in Easy Rider (1969) and ordering toast in Five Easy Pieces (1970), it was his best role up until that point, setting the stage for his first Oscar win for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). It remains one of his most memorable for unfolding largely with a bandage over his nose, thanks to a snippy cameo from Polanski: “You know what happens to nosy fellas, don’t ya? They lose their noses.”

But the Oscar-nominated performance runs much deeper than any bandage. In essence, Nicholson has placed an emotional bandage over his past scars. He’s a lonely character haunted by something that happened in Chinatown: “I was trying to keep someone from being hurt. I ended up making sure that she was hurt.” His haunted past is hinted at by a series of Chinese references, including a “screw like a Chinaman” joke, a groundskeeper providing a clue with “grass” vs. “glass,” and Buck Henry’s final line: “Forget it Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

![]()

Dunaway & Houston: Victim & Villain

Playing the doomed damsel is Dunaway, wholeheartedly earning her Oscar nomination in projecting the deeply scarred Mrs. Mulwray. While she functions as a femme fatale, she is less an evil puppetmaster, and more a disturbed woman trying to hide the dark secrets of her father. Note the way Dunaway touches herself whenever Jake mentions her father. It’s a genius acting choice that you only notice on repeat viewings.

No, the real scoundrel is Noah, a seemingly gentle old man with a most dark interior. Who better to play the role than John Huston, who pioneered the film noir genre with The Maltese Falcon (1941)? The Biblical name of “Noah Cross” was likely a nod to Huston’s role as Noah in his self-directed The Bible (1966). Polanski even considered casting Huston’s real-life daughter, Anjelica Huston, in the role of Evelyn. (D) Thankfully we were spared that layer of creepiness.

Noah Cross was recently named the AFI’s No. 16 Villain of All Time, ahead of Annie Wilkes in Misery (1990) and The Shark in Jaws (1975). As much as viewers will hate the character, they must give it up for Huston, who creates one of the most horrific characters of all time, all the more empowered by Polanski’s cynical vision: “You see, Mr. Gittes, most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place, they’re capable of ANYTHING.”

![]()

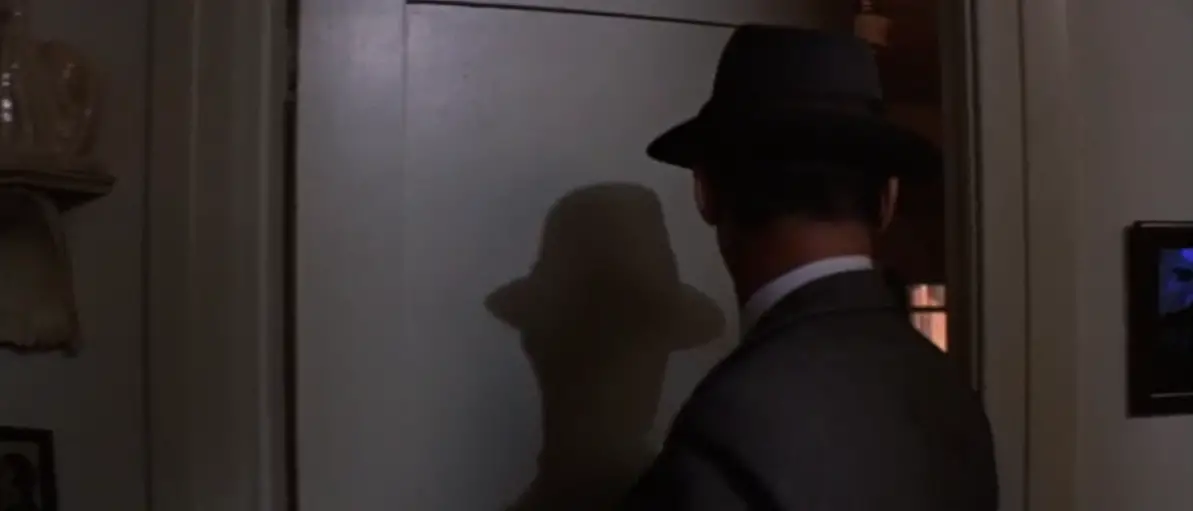

Voyeuristic Reflections

Jake’s investigation is told through several reflected images; reflections of Jake’s past as a confident gumshoe who’s ultimately doomed. Note the reflections in both the side mirror of Jake’s car and the lens of his camera.

Polanski’s direction is almost like a detective himself, placing great attention on the tiniest details, planted so inconspicuously that we eagerly study them all, sometimes useful (a newspaper clipping), sometimes not (the desk drawers), but always engaging.

We become Gittes with a collection of subjective shots (binocular POVs) or near subjective shots looking just over Nicholson’s shoulder, subconsciously making the narrative all the more personal.

![]()

Foreshadowing & Parallelism

The real genius of Polanski’s direction is his use of parallelism to create a cyclical notion of fate. Like the fatalistic car rides of Out of the Past (1947), Polanski hints at the film’s tragic conclusion: Evelyn being shot through her left eye (our right on screen) with her head pressed against the steering wheel, her wound visible as the police open her car door.

Polanski brilliantly foreshadows this conclusion with a number of audial and visual elements. It’s stuff you may not notice on first watch, but which make repeat watches all the more impressive.

The first time we see Noah Cross in Jake’s photograph, he is visible through a steering wheel, which blocks Hollis Mulwray. After Jake publishes what he believes is Mulwray’s affair in the newspaper, a car horn blares outside the window as the vehicle overheats, to which Jake’s barber says, “This heat’s murder.” A fellow barbershop customer says, “Fools’ names and fools’ faces,” criticizing Jake’s profession as “a hell of a way to make a living.”

Later, midway through the film, Evelyn’s head casually droops toward the steering wheel and accidentally hits the car horn, foreshadowing her demise with a blaring car horn.

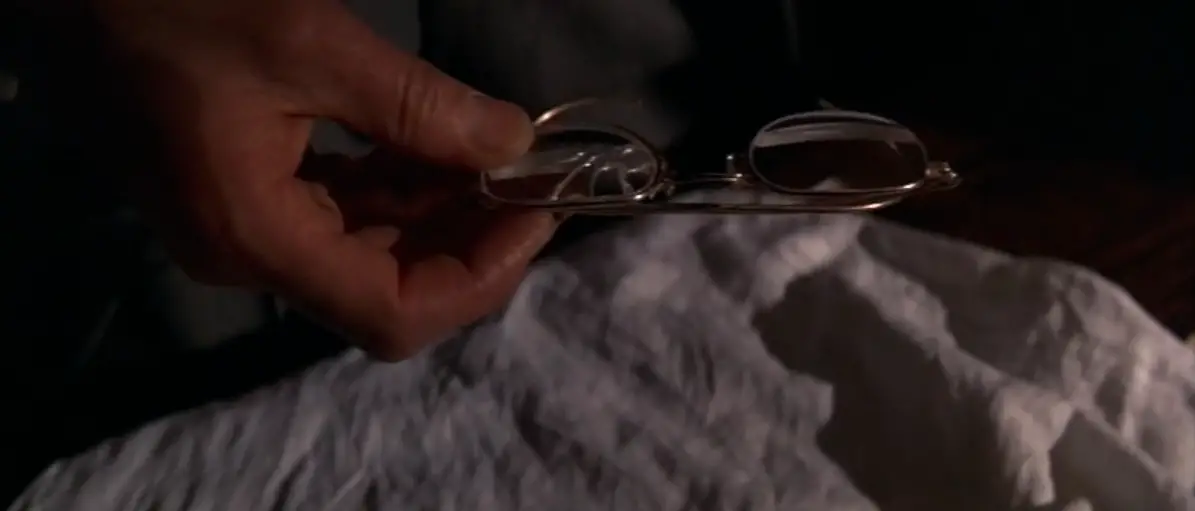

Note how the LEFT lens of Jake’s sunglasses is broken when he is roughed up in the orange grove.

Note also how the LEFT lens of the bifocals is missing when Jake finds them in the backyard pond.

Perhaps most directly, note how Jake points out that Evelyn’s LEFT iris has a flaw in it. Indeed, it is a fatal flaw.

![]()

The Sights & Sounds of Neo-Noir

All the directing in the world would not have mattered if it weren’t for John A. Alonzo’s Oscar-nominated Cinematography. Alonzo creates a mood with light and shadow that took the black-and-white noir elements into a sepia-toned neo-noir era. It would be the only Oscar nomination of his career, despite shooting such classics as Harold & Maude (1971), Norma Rae (1979) and Scarface (1983).

Melding with the Oscar-nominated cinematography was the Oscar-nominated score of Jerry Goldsmith. It was the seventh nomination of Goldsmith’s career, after classics like Planet of the Apes (1968) and Patton (1970), and two years before his Oscar win for The Omen (1976).

While his “Chinatown” score lost to Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola for The Godfather: Part II (1974), Goldsmith has gotten the last laugh as “Chinatown” was voted the AFI’s No. 9 Greatest Film Score of All Time. The music is the best of his career, a collection of wailing trumpets that can almost make you cry. You can hear echoes of it in Alvin Silvestri’s “Eddie’s Theme” in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988) and Goldsmith’s own music for L.A. Confidential (1997).

![]()

Pop Culture

Such musical references aren’t the only pop culture callbacks. The film inspired the entire plot of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), replacing the water scandal with the highway scandal. Scholar David Thomson says Chinatown writer Robert Towne was itching to go in this direction himself: “Even in the 1970s, Towne dreamed of carrying his hero, Jake Gittes, into the 1940s and 1950s as L.A.’s water problems turned into the story of gasoline and automobiles.”

Spaceballs (1987) references the Chinatown line, “When you’re right, you’re right. And you’re right.”

The Simpsons had an episode called “The Secrets of a Successful Marriage” (1994) where they say: “Forget it Marge, it’s Chinatown.”

In The Truman Show, Truman coughs to conceal that he is ripping a page from the fashion magazine in his office. This references when Gittes coughs to conceal that he is ripping a page out of book with a list of the names of the grove owners in the valley.

In Vin Diesel’s XXX (2002), Cage makes a joke telling El Jefe he’s short. Later in the same scene, El Jefe threatens to cut off Cage’s nose the same way Polanski threatens to cut off Gittes’ nose in Chinatown. The “Whitecaps” episode of The Sopranos references the “bad for the glass” line. The “First Cut is the Deepest” episode of Grey’s Anatomy features the “I’m your sister, I’m your daughter” line. The movie Hot Fuzz (2007) uses the line “Forget it, Nick. It’s Sandford.” And a 2012 episode of 30 Rock, Jenna says “Forget it, Tracy. It’s Midtown.”

The animated Rango (2011) features a similar “control the water” plot and Noah Cross-like mayor.

Still, the most obvious reference is the sequel The Two Jakes (1990). Once again, Jake is told: “You may think you know what’s going on around here, but you don’t.”

![]()

Twisted Legacy

The failure of The Two Jakes (1990), directed by Towne himself, shows the importance of Polanski’s involvement in the original Chinatown. In a disturbing way, Polanski was the perfect man for this type of movie, as he himself proved to be capable of anything.

Throughout the film, Polanski maintains a most fatalistic worldview, with both Jake and Evelyn unable to escape a past that’s destined to destroy them. There’s no redemption for the hero, the innocent heroine is wrongly punished, and, in one of those rare movie occasions, the bad guy wins. Jake, and we the audience, have to just sit there and take it, anguishing in the inevitable tragedy captured in five words: “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

The villain’s ultimate escape may turn off many a mainstream viewer, but this is precisely Polanski’s point: that the literal and figurative raping of a city’s citizens occurs everyday and often goes unpunished. The ending, while dark, is tragically appropriate.

Towne’s script originally ended with Evelyn safely escaping with her daughter, but Polanski insisted it be changed to the bleaker conclusion that’s in the film today, as his cynical worldview had been shaped by a similar life experience. He was born to Polish parents, one of whom died in Aushwitz. By thte time Chinatown came along, it was his first Hollywood film since the grisly 1969 Manson murder of his pregnant wife Sharon Tate, and many doubted Polanski could ever recover. Chinatown was a monumental career resurgence, the greatest film Polanski ever made, and ironically his last in the U.S.

That’s because in 1978, he was convicted of statutory rape for having sex with a 13-year-old during a photo shoot at the home of Nicholson. Nicholson wasn’t home at the time, but his wife, Anjelica Huston was. After fleeing to Europe, Polanski was able to salvage his career, directing box office hits like Frantic (1988) and critically acclaimed pieces like The Pianist (2002), which earned him the Golden Palm at Cannes and the Academy Award for Best Director. Polanski didn’t risk the trip to Hollywood, where he surely would have been arrested. In 2009, more than 30 years after the charges, Polanski was finally arrested while attending the Zurich Film Festival in Switzerland.

In this light, or should we say, in this shadow, Chinatown remains all the more chilling. It highlights the fine line in so many artists, where artistic genius brings brilliant insight into the dark world around us, but renders them unable to safely navigate their own existence. Throughout his career, Polanski kept returning to the theme of rape, be it a girl having hallucinations of sexual abuse in Repulsion (1965), a newlywed being raped by Satan in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), or the incest here in Chinatown, where literal human rape coincides with the metaphorical rape of the land and its water supply. The film is both the pinnacle of his artistic expression and the red flag for his personal failings; a superbly crafted piece of storytelling whose real-life underpinnings make it tragically transcendent.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: Cinema and the City, p. 46-47, 56-58

CITE C: Blake Snyder, Save the Cat

CITE D: Tim Dirks, Filmsite.org