Director: Dziga Vertov

Screenplay: Dziga Vertov

Photography: Dziga Vertov

![]()

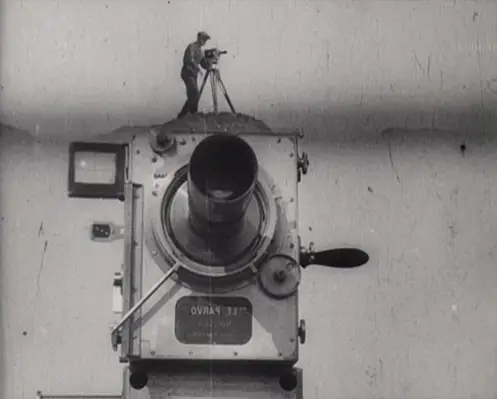

Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929) has got to be one of the most endlessly fascinating films ever made. Where else can you find such a textbook example of Soviet montage, experimental narrative and raw documentary all rolled into one? The combination forms the epitome of the “city symphony”, capturing the ongoing dance between the modern man and his machines. How fitting, then, that the film begins with a composite image of a man standing on top of a camera, as if to say mankind has finally achieved the ultimate in technology — the cinema –humanity’s most powerful instrument at capturing its own existence.

Vertov seems determined to strip down the film medium and show how it works from the inside out. From start to finish, the film casts a self-reflective eye on the cinematic process, making us entirely aware of its apparatus (the camera), while exposing a number of filmmaking elements in a sort of cinematic crash course.

The Movie-going Experience. The film starts by taking us inside an actual movie theater, where the seats come down automatically. From these seats, an on-screen audience stares back at real-world viewers, transforming the movie screen into a mirror, possibly for the first time.

Perspective. There’s a point in the film where Vertov intercuts an eyeball’s rapid movements with a collection of whirling camera angles. The intercutting becomes an orgy of perspective, showing us various points of view from an eyeball looking in various directions. Ultimately, the eye is superimposed over a camera lens, forming a literal “cinematic eye”.

Camera set-ups. The idea of perspective is expanded to explain the concept of camera set-ups. Early on, we get a low-angle shot of a horse-drawn carriage. Then, we cut back to a wide angle to see the Man With a Movie Camera (MWAMC) lying on the ground to record that very shot of the carriage. In another example, we see the MWAMC shooting footage from the sides of two separate trains. When these two separate set-ups are composited as side-by-side images in the same frame, we see just how easily these camera set-ups can be manipulated.

Tracking Shots. In another instance, we watch the MWAMC ride in a car and film a horse-drawn carriage riding next to him. Seconds later, we see what the camera sees – a moving object (the carriage) in a moving frame (due to the camera moving next to the carriage). It’s a physical demonstration of a tracking shot.

Crane Shot. The idea of a moving camera affecting the image continues later in the film with a head-on shot of the MWAMC in a lobby. Suddenly, our frame rises and we realize we’re riding an elevator. As the elevator reaches the next floor, the MWAMC disappears from view. When the elevator returns to the first floor, we find the MWAMC exactly as he was before. Here, Vertov has demonstrated the idea of a “crane” or “boom” shot, showing how cinematic space can be affected verticality.

Shutter. Early in the film, Vertov intercuts three images — window shutters, a blinking eye and an actual camera shutter closing around a lens. Here, Vertov has shown how camera shutters serve the same function as window shutters and eye lids – controlling the amount of light that gets in.

Camera Mechanics. Staying true to the concept of the city symphony, Vertov populates his film with numerous machines and urban gadgetry. More importantly, these machines help describe how a film camera works on a functional level. Images of churning bicycle wheels, sewing machines, revolving doors, train drive shafts, pistons and gears are not so different from the spinning reels of a film projector, just as a cashier cranking open a cash register or a man cranking open his store window are not so different from a camera operator hand-cranking his movie camera.

Breaking the Fourth Wall and Actor Awareness. About mid-way through the film, there’s an extreme high angle where the MWAMC’s camera looks down on the city with a bird’s eye view. Suddenly, the camera whips around and looks directly at us, demolishing the so-called “fourth wall”. Notice how in subsequent scenes, the on-screen actors are aware of the camera. They begin hiding their faces, ashamed of their divorce, or whatever embarrassing moment the script calls for. The illusion of the cinema has been broken. They’re on candid camera.

The Editing Process. I save this example for last, as it is the most fascinating. There’s a point in the movie where the film actually stops and an editor has to decide what image to cut to next. Using freeze frames on people’s faces and a galloping horse, Vertov draws attention to the fact that film is nothing more than a collection of still images. He takes us visually through the entire process – (A) moving image, (B) still image, (C) a single film strip, (D) a choice of multiple film strips, (E) an editor cutting the film strips, (F) back to the moving image. Vertov also juxtaposes images of film stock treatments with images of a manicurist filing fingernails and a hair stylist cutting hair. It’s all fine craftsmanship, full of detail, and to send the point home, spools of yarn become spools of film.

Man With a Movie Camera is constantly up to something, inquiring, teaching, divulging. What’s all the more impressive is how dazzlingly fast it moves. Vertov seems obsessed with pushing the envelope and earning the “spinning top” translation of his own name. As Gerald Mast writes in A Short History of the Movies, the film dabbles in everything from accelerated motion to split screens to superimpositions to stop-motion animation. While these out-of-the-box techniques are impressive, I am most impressed by the out-of-the-box concept of exposing film’s inner workings. The fact that a film from 1929 could be so post-modern shows just how far Vertov was ahead of his time, while cementing the argument that Man With a Movie Camera is the greatest “movie about movies” ever made.