Director: Sam Mendes

Writer: Alan Ball

Producers: Bruce Cohen, Dan Jinks (Dreamworks, Jinks/Cohen)

Photography: Conrad L. Hall

Music: Thomas Newman

Cast: Kevin Spacey, Annette Bening, Thora Birch, Wes Bentley, Mena Suvari, Chris Cooper, Peter Gallagher, Allison Janney

“Never underestimate the power of denial.”

![]()

In the discussion of strong vs. transparent filmmakers, the conventional wisdom seems to be that the strong have become a relic of the past. Sam Mendes is one of those rare exceptions, or at least he thus far appears to be. With a string of efforts including Road to Perdition (2002), Jarhead (2005) and Revolutionary Road (2008), Mendes has made quite the name for himself. And yet, it’s hard to imagine how he will ever top his debut, American Beauty, which beckoned today’s audiences to “look closer” in a way they are not asked often enough.

As a result, the film dominated the Academy Awards in a way first-time directors can only dream, winning five — Best Actor (Kevin Spacey), Best Director (Mendes), Best Original Screenplay (Alan Ball), Best Cinematography (Conrad L. Hall) and Best Picture (Bruch Cohen, Dan Jinks). It was the first non-historical epic to win Best Picture in eight years, (A) and it’s easy to see why. Has there been another film in recent years that has inspired such simultaneous hope and lament for a self-critical America?

American Beauty completes a sort of post-modern suburban “triology”, becoing the happy medium between Robert Redford’s accessible Ordinary People (1980) and David Lynch’s bizarre Blue Velvet (1986). The film lacks the power of Velvet on the most esteemed best lists, but does better than both Velvet and People in mainstream polls, ranking as high as #38 in the IMDB Top 250 and #51 in the Empire Top 201. However you rank it, all three films cast a brilliantly critical look at the American Dream, kicking to pieces the white picket fences of modern suburbia to see the darkness underneath, stripping the ideal exteriors of society to get down to the true beauty of this world; to stop and smell the roses, so to speak.

Our portal is the Burnham family. The youngest is the quasi-goth only child Jane (Thora Birch), a “typical teenager, angry, insecure, confused.” It’s telling that the film opens with her, as she is the one who most realizes the phony, materialistic existence of her family. She finds a welcome alternative in a stalkerish, video-taping, pot-selling new neighbor, Ricky Fitts (Wes Bentley), who endures the abuse of his homophobic father, retired Marine Col. Frank Fitts (Chris Cooper), whose own identity issues have driven Ricky’s mother (Allison Janney) to a catatonic state.

The problems of the Fitts family are not unique. The Burnhams are well on their way to imploding by film’s start. The dominant figure is working-mother control freak Carolyn (Annette Bening), whose pruning shears perfectly match her gardening clogs and whose personality proves as phony as her faithfulness. She engages in an affair with her real estate idol, Buddy Kane (Peter Gallagher), whose motto echoes her own: “In order to be successful, one must project an image of success at all times.”

It’s this precise worldview that has alienated her husband Lester (Spacey), an adveristing agent who introduces the film like so: “My name is Lester Burnum … I’m 42 years old. In less than a year, I’ll be dead. Of course, I don’t know that yet. And in a way, I’m dead already.” At the start of the film, the high point of his day is masterbating in the shower. He exists in a state of pathetic, mild-life crisis. Then one night, at a high school basketball halftime show, he spots Jane’s slutty dance team friend Angela (Mena Suvari) and begins having wild sexual fantasies about her. In a hilarious quest to recapture his youth, he quits his job, begins sculpting his body to Bob Dylan songs and applies to flip patties at the local Smiley Burger. A perverted goal for sure, his desire for Angela nonetheless sparks a positive awakening, where he learns that life is his for the taking.

The role was tailor-made for Spacey — Mendes’ first choice. His trademark snarky charm was the perfect fit for Lester’s “ordinary guy with nothing left to lose.” Through Spacey, Lester’s mid-life crisis is allowed to cut both ways, as both powerful drama and laugh-out-loud comedy. Who else could sit at a dinner table with such a straight face and deliver this line: “Today I quit my job, and then I told my boss to go f*ck himself, and then I blackmailed him for almost $60,000! Pass the asparagus.” Spacey’s Oscar victory was his second in four years, after his Best Supporting Actor win as the mastermind in The Usual Suspects (1995), marking a powerful string of films that also included Se7en (1995) and L.A. Confidential (1997).

Across from Spacey, Mendes got his other first choice, Bening, who balances the drama and comedy every bit as well as Spacey. Who can forget her trying to sell a piece of real estate; breaking down in tears and slapping herself back into toughness; screaming “your majesty!” during sex with The King; telling herself she will “not be a victim”; and clutching her husband’s clothes as she falls heartbroken in his closet? Bening not only earned her second nomination (The Grifters), she also won an American Comedy Award.

Much of the credit for the comedic-dramatic tightrope belongs to screenwriter Alan Ball, who later went on to create the hit TV seris Six Feet Under. Voted the #35 Greatest Script of All-Time by the Writers Guilds, American Beauty insists on giving every character ample thought, developing each with his or her own sub-surface problems in a brilliant ensemble character study. Not a single one is wasted — not Angela, who talks a good game but has her own confidence problems; not Jane, who searches for comfort in her own skin; not Ricky’s mother, who sits frozen in an unfulfilled marriage; and certainly not Colonel Fitts, who suspects something fishy going on between his son and Lester, though it’s not quite what he thinks.

The Colonel Fitts character may be the most fascinating (and pivitol) character study in the entire film. He’s a who adheres to an ideal that Ball’s script vehemently challenges: “You can’t just go around doing whatever you feel like. You can’t! There are rules in life! You need structure!” Such a quote parallels a particular couch scene between Lester and Carolyn that provides insight into their crumbling marriage, while speaking volumes to the film’s theme of impulsive vs. structured living. Ball suggests that it can be liberating to live by impulse, as Lester experiences, but it can also be dangerous, leading to his ultimate demise.

It’s here, on the subject of Lester’s death, that Ball works his most brilliant magic, beginning American Beauty with the protagonist narrating from the grave about his own death. This, of course, borrows from Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. (1950), to the point that Mendes dedicated his Oscar to him: “If my career amounts to one-tenth of what yours has been, I’ll be a very, very happy man.” (B) The beyond-the-grave narration not only introduces us to Lester’s world, it later signals that we’re on the home stretch: “Remember those posters that said, ‘Today is the first day of the rest of your life’? Well, that’s true of every day but one – the day you die.” What a fascinating ride to know that the main character is going to die, and what skill to slowly peel away the events that lead up to his death. From start to finish, Ball plays with our expectations as to who the killer might be. A wife? A daughter? A neighbor? Ball continues the mystery even after the deed is done, hiding the act by panning away seconds before the gunshot (a la Pickup on South Street), narrowing the possibilities by showing the shocked reactions of those who did not do it, and ultimately showing the visual evidence for the one who did.

What would this powerful conclusion be without Mendes? He was a British stage director when Steven Spielberg chose him to direct Dreamworks’ new project. Spielberg read the script, said don’t change a thing, and turned it over to Mendes, who later said, “I would have done this movie for free. And I almost did. I think Steven Spielberg owes me a couple of quid.” (B)

The pacing and build-up of the climax and its aftermath are masterful, intercutting the present situation with Lester’s life flashing before his eyes, all shot and cut to look like one continuous horizontal dolly. It’s just one example of Mendes the filmmaker, clever, strategic, and all right out the gate. As a former theater director, one would expect him to get good performances out of his actors. The surprising part is how good he is at utilizing film as a visual medium.

His understanding of mise-en-scene is uncanny, whether it’s characters spaced out at a lonely table (the camera reluctantly pushing in), or an extreme long shot of Jane and Ricky walking home from school (turning rows of trees into a figurative cathedral of truth). Each composition is made all the prettier by veteran cinematographer Conrad L. Hall, who earned his second Oscar, after Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969), and his first of two working with Mendes. Hall would win his third Oscar posthumously for Road to Perdition.

Still, the most obvious example of mise-en-scene in American Beauty relates to the title itself. In a brilliant touch, Mendes symbolically fills his frames with actual American Beauty roses — a species of flower that looks and smells beautiful on the outside, but has a rotten-smelling core. Considering this, you’ll never look at the Burnham dinner table bouquet the same. What was once just a pretty centerpiece now becomes a symbol of suburbia’s rotten core. And by the time Lester holds a family photo overtop that bouquet in his final moment of peace, the symbolism is at its peak.

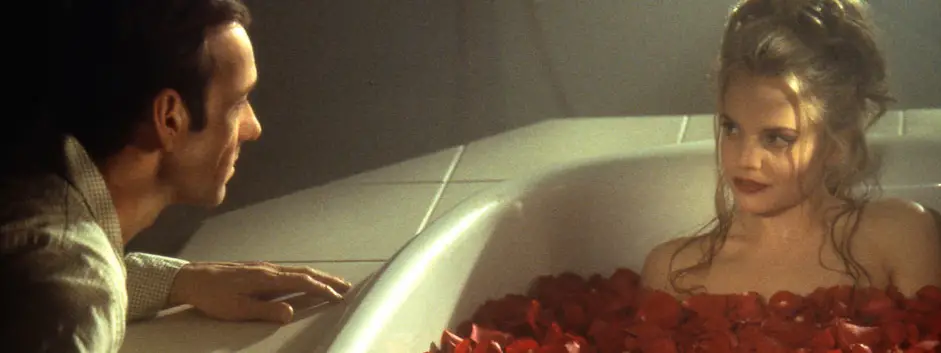

The roses become a running motif throughout the entire film, from Carolyn’s garden to Jane’s sweater, and appear most noticably in Lester’s trippy sex fantasies. Thousands of rose petals were digitally created for these dream sequences — exploding out of the chest of Angela’s dance outfit; pinning her to the ceiling of Lester’s bedroom and replacing the water in a bathtub. These scenes may be off-putting to the most straight-laced viewer (one IMDB user complained of “child pornography”), but to most open-minded thinkers, they represent an abstract interpretation of man’s perverted desires, which Lester ultiamtely overcomes in the face of lost innocence. At the very least, they show Mendes’ potential as an experimental director.

My favorite piece of Mendes mise-en-scene is a subtle touch that symbolizes the pain Ricky’s mother feels at being married to a closet homosexual. Look closely at how Mendes features a red oven mitt over the stove as Ricky’s mom fries up some bacon. Is Mendes intentionally calling attention to the fact that Ricky’s mother is, metaphorically, trying to make shriveled up meat harder? Or was it a happy accident? Either way, it’s there. And you can see it if you just “look closer.”

In addition to symbolic mise-en-scene, Mendes also pushes the boundaries of voyeurism and perspective. The film opens with Jane breaking the “fourth wall” by staring directly into the camera. This is, of course, the grainy perspective of Ricky’s handheld camcorder, a perspective we assume multiple times throughout the film. What starts as a creepy watchful eye, becomes a record of life’s beauty and a clever way to reveal character. Note Ricky’s zoom-in past the “ideal” Angela to focus in on the “ordinary” Jane. In doing so, we learn that Ricky (and Mendes) view Angela as the ordinary one and Jane as the ideal one.

The camcorder also allows for some fascinating compositions, like Ricky holding his camcorder in the right of the frame as he films out his window, while Jane appears in a live video feed on Ricky’s television in the left of the frame. Like Soderberg showed in sex, lies and videotape (1989), the home camcorder is a luxury that voyeurs like L.B. Jeffries did not have in the days of Rear Window (1954). Only this tool leaves a bread crumb trail, evidence of one’s once-private gaze.

Ironically, Mendes is able to show voyeurism as more than just a perverted activity. Ricky explains that he films things as his only way to capture and save moments of blinding beauty, like that of a plastic bag floating in the breeze. As Ricky describes footage of the mundane event in sacred terms, Thomas Newman’s pondering, Grammy-winning piano lifts the scene toward the heavens:

“It was one of those days when it’s a minute away from snowing and there’s this electricity in the air, you can almost hear it. And this bag was, like, dancing with me. Like a little kid begging me to play with it. For 15 minutes. And that’s the day I knew there was this entire life behind things, and this incredibly benevolent force that wanted me to know there was no reason to be afraid, ever. Video’s a poor excuse, I know. But it helps me remember. And I need to remember. Sometimes there’s so much beauty in the world I feel like I can’t take it, like my heart’s going to cave in.”

The scene is the seminal moment in the entire film, providing a window into Ricky’s worldview and an awakening for both Jane and viewers. It opens our eyes to see the world in different detail; to find the face of God in the eyes of a dead person. In this way, Ricky’s character functions as a proxy for Mendes himself. They are both all-knowing figures, operating on a different plane of understanding, and documenting it all with the best method mankind ever invented — with a camera. American Beauty might as well be one giant piece of Ricky’s footage — curious, disturbing, insightful, and ultimately so beautiful you can’t even take it.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Tim Dirks, filmsite.org

CITE B: Piazza and Kinn, The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History