Director: David Cronenberg

Producer: Stuart Cornfield, Marc Boyman, Kip Ohman (Brooksfilms)

Writers: George Langelaan (short story), David Cronenberg and Charles Edward Pogue (screenplay)

Photography: Mark Irwin

Music: Howard Shore

Cast: Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz, Joy Boushel, Leslie Carlson, George Chuvalo, Michael Copeman, David Cronenberg, Carol Lazare, Shawn Hewitt

![]()

“Be afraid. Be very afraid.”

Aside from being the most famous tagline in movie history, Geena Davis’s quote sums up everything one needs to know about The Fly, except for the much needed warning, “And also be ready to grab your vomit bag.” Indeed, David Cronenberg’s 1986 masterpiece is not for the faint of heart, nor the weak of stomach, living up to the director’s reputation for well-placed gore. It’s as if Cronenberg deserves the title of “gore auteur,” carrying his same fascination with mutated human minds and body parts throughout his work. Look at Rabid (1977), which cast porn star Marilyn Chambers as a vampire with an impaling device in her armpit; The Brood (1979), documenting the attacks of mutated children; Stephen King’s The Dead Zone (1983), on the subject of psychic powers; and the masterpiece Videodrome (1983), where a human body comes complete with a virtual reality outlet, not so different from The Matrix (1999) (A). The Fly was a natural next step in this filmography, and lucky for us, it is so much more than its stomach-turning premise.

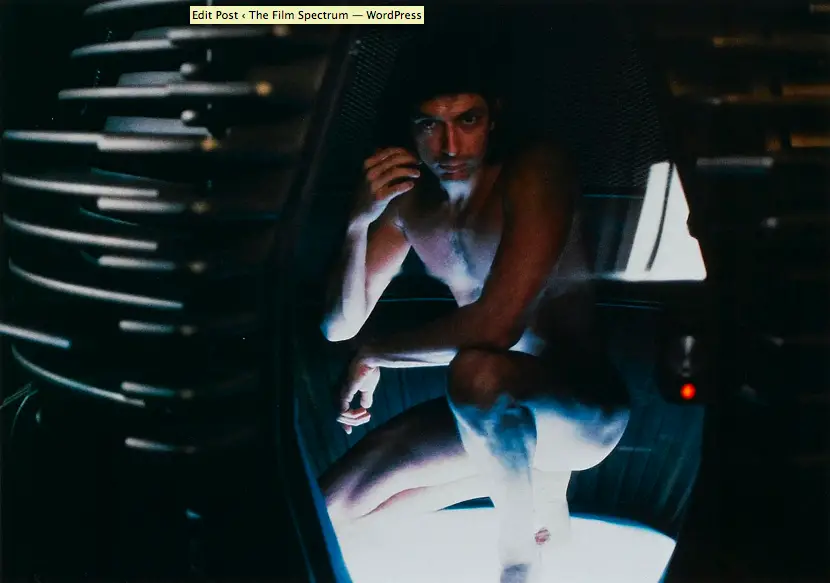

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) is an overly ambitious scientist who’s on the brink of discovering human teleportation. He’s designed a matter transporter, able to dissintigrate matter and then reassemble it across the room using telportation chambers called telepods. So far he’s succeeded in transporting only inanimate objects, as his experiments with live animals are producing bloody results. In walks Veronica Quaife (Davis), a journalist who sees Seth’s invention as her big career break and who can’t help but fall for Seth’s charming genius. As Seth promises Veronica this major scoop in a book collaboration, the two fall in love and seem to be on their way to millions…that is until one night Seth, in a drunken state, cannot wait any longer to try teleporting himself. The experiment succeeds, sending Jeff across the room, but unbeknownst to him, he shares the telepod with a common housefly. The result: both species are teleported at once, the computer becomes a gene-splicer, and both DNA structures are fused into one, creating what Seth later hilariously calls a Brundle-Fly.

Almost immediately, Veronica begins noticing erratic behavior from Seth. Not only does he become a superior athlete and extra-durable lovemaker, he becomes twitchy, hyper and constantly craving sugar. What’s more, he seems obsessed to get her to teleport as well, urging that one “dive into the plasma pool” and you feel like a brand new person, full of energy and purpose. The high is only temporary though, and soon Seth begins noticing the true effects of his curse — that he is indeed transforming into a six-foot-tall fly. Think Spider-man, but terrifying.

Such material sounds more like the stuff of a movie of the week, a B horror flick. That’s because the original 1958 version of The Fly, starring Vincent Price, was exactly that. The reason Cronenberg’s remake succeeds is partly because he casts it so well. Davis, a little-known actress in films like Tootsie (1982) and Fletch (1985), found her breakthrough role here as the emotional core of the film. Equally as good is John Getz (Blood Simple), who plays Davis’s crazy ex-lover to sleazy fascination. What fun he must have had in developing his character, working from the simple, hysterical premise of always saying the wrong thing at the wrong time. Most impressive, of course, is Goldblum, who finds real romantic chemistry with Davis, whom he would marry the following year. Goldblum had been gaining popularity with audiences for about a decade, moving from bit parts in Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975) and Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) to larger roles in films like The Big Chill (1983). The Fly was no doubt Goldblum’s breakthrough, cementing that now-signature Goldblum reading, sarcastic as hell and seeming as if he’s making up the dialogue as he goes. Many, including Roger Ebert, were dumbfounded when Goldblum did not receive even an Oscar nomination. One viewing of this film and one has to respect the guy. His transformation from human to fly rivals any on-screen deformation, as sad as Laughton’s Quasimodo (1939), as tragic as Hopkins’ Elephant Man (1980). Goldblum completely masters the gradual changes to his character’s appearance and psyche, bugging his eyes out and jerking his movements only to coincide with his uber-hyper behavior.

But Goldblum’s performance was only half the battle in getting audiences to buy the transformation. The other half belonged to the art department and visual effects crew, who each have a field day, from Chris Walas’ mechanical, Terminator-esque bug creature, to Rob Bottin’s prosthetics of crumbling, goo-spewing body parts, to Carol Spier’s design of the telepods (modeled after the motorcycle cyllinders in Cronenberg’s garage) (B). By the time Seth’s “disease” is full blown, wrapping Goldblum in a grotesque insect suit, we believe the progression of Goldblum’s physical changes, if not entirely believing in the end visual of Goldblum’s costume. No doubt the visuals have dated, as has the computer interface Seth uses to conduct his experiments. Some may even argue that the internet age has softened the novelty of transporting matter. In 1986, however, these visuals were spectacular, earning a Best Makeup Oscar for Walas and Stephan Dupaus. And for a film that relies so much on the effects, it’s a feat in itself that the film dates only slightly, and certainly not enough to ruin the viewing experience.

One thing completely unaffected by time is the script. Co-written by Cronenberg and Charles Edward Pogue, the screenplay is at once science fiction, horror, screwball comedy, and tragic romance. Just as Seth’s computer serves as a gene-splicer, The Fly is a bonified genre-splicer, and the cross-genre fusion is more beautiful than anything the film could have done in one or the other. How else can you get a moment like Goldblum singing, “I know an old woman who swallowed a fly,” and have it play so simultaneously creepily and hilarious? My personal favorite exchange: “Talk to the tape. … The world will want to know what you’re thinking,” “’Fuck’ is what I’m thinking!” “Good. The world will want to know that.” These screenwriters are smart, man, across the board — in their subtle jokes (i.e. a drunk woman wanting to drink more because Seth’s face is disgusting), in the way they set up payoffs (i.e. the business about flies regurgitating acid before meals) and in the way they slowly reveal their character details (i.e. Veronica’s ex; Seth’s wardrobe).

While the slow disclosure of character details and exposition is a testament to Cronenberg the writer, the slow disclosure of images proves a valuable tool for Cronenberg the director. Note how he uses the defined space of the frace to have us wondering what’s lurking outside it, like when Veronica enters her home suspiciously to find the shower running, when her car pulls out of Seth’s place to reveal a stalker, when she enters Seth’s apartment to see his transformed body for the first time, and, most effectively, in the cringing hospital room scene. Note also the emotional impact he creates by fixing his camera at the end of a long hallway and allowing Veronica to approach it, like Hitchcock did for Scottie Ferguson and Nichols did for Benjamin Braddock. Cronenberg’s most genius touch, though is the one he opens his film with, and repeats later in Seth’s apartment — a high angle POV shot from a fly’s perspective, literally a “fly on the wall shot.” Aside from such techniques, Cronenberg proves himself as a master of pacing, structuring his suspense to allow for well-placed gorey effects that would have otherwise been too much. As David Thomson writes, “Horror for Cronenberg is not a game or a meal ticket; it is, rather, the natural expression for one of the best directors working today.” (A)

Scholars like Thomson sing Cronenberg’s praises today, but it wasn’t always that way. When Cronenberg first arrived, many critics didn’t know what to make of his graphic approach. By the arrival of The Fly, however, the verdict was unanimous — Cronenberg was a genius. Today The Fly holds a powerful 91% on rottentomatoes and is a true underdog contender on best lists. TIME magazine, for instance, voted the film into its Top 100 Films of All Time, something not even Gone With the Wind (1939), The Wizard of Oz (1939) or 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) can say. The film’s positive reception inspired a sequel, The Fly II (1989), launched Davis to Thelma and Louise (1991) and Goldblum to Jurassic Park (1993) and assured Cronenberg’s future success in Dead Ringers (1988) and Naked Lunch (1991). What’s more, in 2008, Cronenberg directed an opera version, with music by Howard Shore, the composer of the film’s harrowing score.

How can something so mistakable as a “typical horror flick” make its way into the highbrow circles of the opera? Easy: its themes are that deep. Seth’s transformation can be read as a metaphor for all human disease. Many at the time correlated Seth’s predicament to the growing AIDS epidemic, a claim Cronenberg denied, instead linking it to humanity’s shared incurable “disease” — aging. Whatever the disease, the emotional gravity hits us hardest in the moment when Veronica, realizing her lover has reached a point of unrecognizable deformity, does not back away in horror, but rather pulls him in for a warm embrace. What pathos for a horror film!

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: The Fly DVD booklet