Director: Elia Kazan

Producer: Charles K. Feldman

Writers: Tennessee Williams (play), Oscar Saul (adaptation), Tennessee Williams (screenplay)

Photography: Harry Stradling Sr.

Music: Alex North

Cast: Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, Karl Malden, Rudy Bond, Nick Dennis, Peg Hillias

![]()

“Stella!! Hey, Stella!!!”

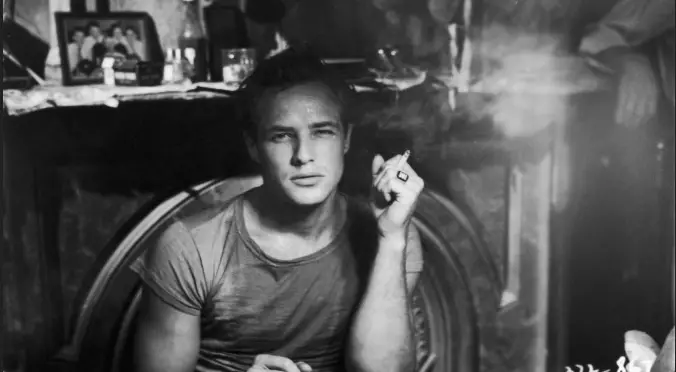

That mournful cry from Marlon Brando in his soaked, torn t-shirt, standing alone in the street, both hands on his head, wailing up to an upstairs apartment to his abused wife, stands as one of the most iconic moments in all of movie history. Ironically, the film A Streetcar Named Desire much more resembles a stage production than it does a film. This is due to Tennessee Williams’ transition from playwright to screenwriter and Elia Kazan’s ongoing shift from stage director to filmmaker.

With him, Kazan brought his entire cast from the original Broadway production, save for Tony-winning lead Jessica Tandy (The Birds, Driving Miss Daisy), whom the studio replaced with Vivien Leigh, an actress of bigger box office potential just a decade after playing Scarlett O in Gone With the Wind (1939). This collection of players, both old and new, would combine for a dazzling display of ensemble acting, making Streetcar one of the best stage-to-film adaptations of all time with pop culture echoes for decades to come.

The story opens in the the French Quarter of New Orleans post World War II, where the mentally unstable Blanche DuBois (Leigh) shows up at the doorsetp of her pregnant sister, Stella Kowalski (Kim Hunter), whom she hasn’t seen since the death of their father back in Belle Reeve, the southern estate that Blanche has mysteriously lost. Stella’s brutish, territorial husband Stanley (Brando) is immediately suspicious, interrogating her about both her property and her past, ultimately revealing that she’s been exiled from her teaching job in Mississippi for seducing a 17-year-old student.

Seeking an escape, Blanche turns to Stanley’s sensitive, bridge-playing buddy Mitch (Karl Malden), but with Stella’s water breaking, she is left at the ultimate mercy of the animal Stanley in a climax of exploding desire and violence. Is it too late for Blanche to outrun her past, or is there still hope in the adoring Mitch? And what will become of Stella and Stanley, whose already volatile relationship may be strained beyond repair?

This juicy story made young actors salivate, both on stage and screen. Streetcar joins Network (1976) as one of only two films ever to win three acting Oscars. Two of those Oscars went to brilliant first-timers in Karl Malden (Best Supporting Actor) and Kim Hunter (Best Supporting Actress). The third went to Leigh, who won her second statue in an utterly haunting sprial toward insanity, from her inability to face the reality of her past — “I don’t want realism. I want magic!” — to the tragic summary of her lonely existence — “I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

For better or worse, Leigh also stands out as the only classically-trained actor in a picture full of groundbreaking Method actors. Like other traditional actors of her day, Leigh approached her craft with carefully predetermined mannerisms and inflections for her character. Then in 1948, Elia Kazan and Bobby Lewis founded the Actors Studio, which began teaching a new style of acting, which came to be known as “Method Acting,” where actors start with the emotional and psychological core of a character and, from there, allow the rest of the performance to arrive organically.

Kazan’s move from stage to screen, bringing Brando with him for Streetcar, was the most important step in bringing this new form of acting to the film industry. This is what makes scenes between Leigh and Brando so fascinating, not to mention the sexual tension. The steam between the two is palatable, with New Orleans heat staining the extra-tight shirt of Brando (purposely shrunk for the film) and Leigh becoming speechless as he removes his shirt across the room. She later returns the favor behind a suggestive curtain. Such visuals create sexual tension long before Brando says, “If I didn’t know you were my wife’s sister, I would get ideas about you.” Brando so admired Leigh’s portrayal that he claimed it was better than Tandy’s original Broadway role.

Is there a more complicated and volatile relationship in all of film than Stanley and Stella? It’s an abusive relationship no doubt, but no matter how rough it gets, there seems to be an ever-present affection: “Stanley’s always smashed things. … I was sort’ve thrilled by it.” Brutish. Raw. Animalistic. Violent. They’re all good descriptors for Stanley, a character who despite alcoholic rages and food falling out of his mouth, is made utterly compelling thanks to Brando’s unprecedented performance. Sadly, Brando’s raw debut was the only principal role not to win an Oscar, losing to Humphrey Bogart for The African Queen (1951) in what some may call “Academy politics as usual,” choosing the long overdue veteran over the fresh rookie. No matter, this was a huge coming out party for Brando, shifting the way actors acted for the rest of time. And for an actor often called the quintessential Method actor, there was no better match than Kazan.

“I want the breath of life from [actors] rather than the mechanical fulfillment of the movement which I asked for. You don’t deal with actors as dolls,” Kazan said, differing from Hitchcock’s “actors as cattle” approach. “You deal with them as people who are, to a certain degree, poets.” (A)

Despite having won the Oscar Best Director on Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), Kazan claims that he hadn’t fully grasped the medium, even by Streetcar, which he felt was little more than a photographed play. (A) He claimed his first cinematically structured film didn’t come until Viva Zapata! (1952), after which he won Best Picture and Best Director again for On the Waterfront (1954) before delivering gems like East of Eden (1955), A Face in the Crowd (1957) and America, America (1963). Even if Streetcar isn’t his most daring from a directing standpoint, Kazan has a few nice touches.

With the help of Oscar-winning Set Direction, Kazan built the set walls to be movable, taking out little flats as the film progressed so that he could create the effect of the walls closing in on Blanche. (A) While the walls would move, his camera would not, as Kazan nailed down his camera and created movement with pans and zooms rather than dollies or cranes. In this light, his most effective technique is a zoom to a close-up, coming at a precise moment of a character’s inner thought.

Aiding greatly in this regard is the Oscar-nominated score by composer Alex North, who broke the tradition of scoring based on outward character action and instead reflected each character’s psychological state. The score was named one of the AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores of All Time, and North would provide another Oscar-nominated score for another stage-to-screen adaptation, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

But no matter the influence of Brando, Kazan or North, most of the credit belongs to Tennessee Williams, who created truly complex characters in a world where death and desire are opposites that can collide with all the friction of crashing streetcars. In addition to stellar story structure, Williams peppers his script with eloquent prose, radiant on both stage and screen, particularly Blanche’s lecture to Stella on the nature of Stanley:

BLANCHE: “He’s like an animal. He has an animal’s habits. There’s even something sub-human about him. Thousands of years have passed him right by and there he is, Stanley Kowalski, survivor of the stone-age, baring the raw meat home from the kill in the jungle, and you, you’re waiting for it. Maybe he’ll strike you, or maybe grunt, kiss you, that’s if kisses have been discovered yet. … Baby, we are a long way from being made in God’s image, but Stella, my sister, there’s been some progress since then. Such things as art, as poetry, as music. In some kinds of people, some tenderer feelings have had some little beginning that we have got to make grow and cling to and hold as our flag in this dark march toward whatever it is we’re approaching. Don’t. Don’t hang back with the brutes!

Streetcar was Williams’s second big stage success after The Glass Menagerie in 1945, and it won his first of two Pulitzer Prizes, including Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955. But while some praised Williams as brash and innovative, others deemed Streetcar unfit for the movies. Drastic changes had to be made in order to meet the Production Code censors, including scrapping a homosexuality angle, softening the rape scene and altering the ending. Further changes had to be made to avoid condemnation by the Legion of Decency, with Kazan removing dialogue, re-editing scenes and even toning down North’s sultry score. A half century, 12 Oscar nominations, numerous best lists and a restored DVD later, Kazan has gotten the last laugh, bursting out with big Brando machismo, “Ha! Ha!”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: George Stevens Jr, Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age