Director: Martin Scorsese

Producers: E. Lee Perry, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan T. Taplin

Writers: Martin Scorsese and Mardik Martin (screenplay)

Photography: Kent L. Wakeford

Music: Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Bert Holland

Cast: Harvey Keitel, Robert De Niro, David Proval, Amy Robinson, Richard Romanus, Cesare Danova, Victor Argo, George Memmoli, Lenny Scaletta, Jeannie Bell, Murray Moston, David Carradine, Robert Carradine, Lois Walden

![]()

Introduction

Throughout the arc of movie history, a certain few filmmakers step in with their own voice, telling their own personal tales, from the streets of their own neighborhoods, and enrich the rest of our culture in the process. Martin Scorsese’s flickering film projector is a flickering flame we long to touch, knowing we’ll get burnt, yet one that attracts us like movie moths, eternally mesmerized by its dancing flame.

Our fascination with film violence has never been in short supply, but without Scorsese, we could have never truly grasped crime’s contradiction with our better angels, the human quest for redemption in the face of immoral deeds and the eternal struggle between faith and doubt. We would never have learned the thrilling realization that traditional notions of plot could be cast aside in favor of compelling character studies. The streets of New York would seem a little darker, duller. The faces of DeNiro, Keitel and Pesci would be non-existent. And God knows The Rolling Stones wouldn’t sound the same.

Thankfully for us, the man’s brash new voice, his gift, could no longer be contained by the early ’70s. Cult director Roger Corman had noticed Scorsese’s NYU student films and agreed to produce Scorsese’s B-picture Boxcar Bertha (1972). The rest is history. Where would the movies be without Martin Scorsese? And where would he be without Mean Streets?

![]()

Plot Summary

No matter how many better films Scorsese makes, Mean Streets will forever remain his most personal. The semi-autobiographical picture taps directly into the experiences he had growing up in New York City’s Little Italy in the late ’50s. Here, his on-screen proxy is Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel), a slick young man running the streets with other small-time hoods in an attempt to make it in the world of organized crime. Scorsese himself provides the voice-over narration of Charlie’s thoughts, literally serving as the voice inside his head.

From the opening shot, Charlie is presented as a character of intense internal struggle. He loves girlfriend Teresa (Amy Robinson) but worries she’s tainted by her epilepsy. He’s attracted to a stripper but can’t get over the fact that she’s black. And most of all, he tries squaring his life of crime, once the business of his father, with his own religious convictions.

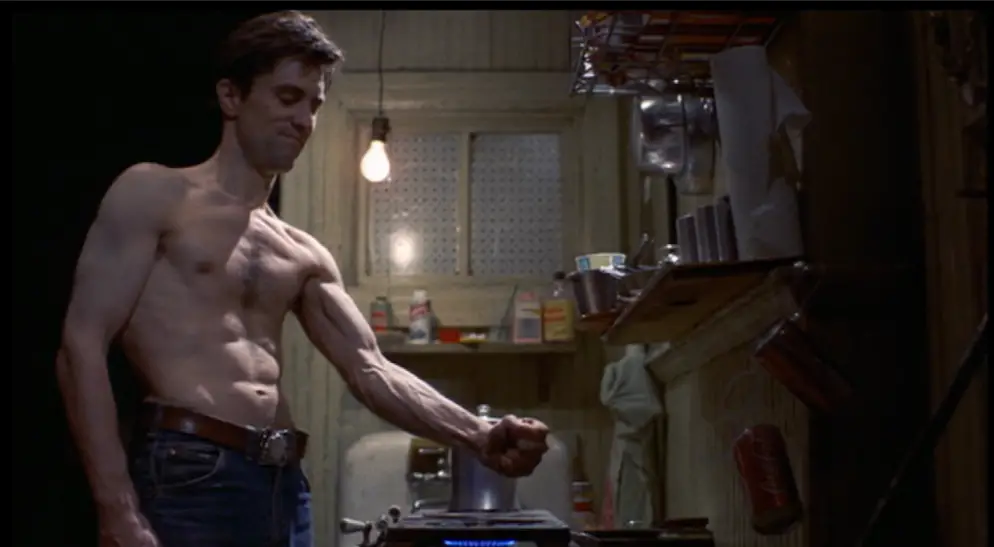

On the one hand, he recognizes the Catholic Church as a man-made organization, a business not so different from organized crime, capable of human flaw. He tells himself, “You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets.” On the other hand, he hangs a crucifix on his bedroom wall and holds his hand over open flames to scourge his own sin (the first of many connections to Taxi Driver):

CHARLIE: “Pain in hell has two sides, the kind you can touch with your hand, the kind you can feel in your heart, your soul, the spiritual side, and you know, the worst of the two is the spiritual.”

This internal spiritual battle fuels his obsession with “saving” Teresa’s cousin, Johnny Boy (a breakthrough Robert DeNiro), a reckless punk who bombs mailboxes, picks bar fights by swinging pool sticks on the pool table, and will be the downfall of all his friends if they keep him around long enough.

Everyone, including Teresa, urges Charlie to distance himself from Johnny Boy, but Charlie somehow feels a moral obligation to stick with him:

CHARLIE: “Who’s gonna help him if I don’t? That’s what’s the matter. Nobody tries no more, tries to help us all, help people. … Francis of Assisi had it all down.”

TERESA: “What are you talking about? St. Francis didn’t run numbers.”

All the while, Charlie comes of age doing all the things Scorsese did in his adolescence: going to clubs to show off female arm candy, taking target practice from the rooftops and scamming students out of money to finance trips to the movies, namely John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and Corman’s British masterpiece Tomb of Ligeia (1964). In the end, Johnny Boy pisses off a loan shark (Richard Romanus), leading to the inevitable shootout and car wreck that leaves Charlie and company a bloody mess.

![]()

DeNiro & Keitel: Two Stars Are Born

Not only was the film a breakthrough for Scorsese, it launched two gritty new stars in Harvey Keitel and Robert DeNiro. Both were no-names before and made men after. But the extent of each’s rise is most fascinating, as it was Keitel who was supposed to be the superstar that DeNiro became. He was, after all, the lead in Mean Streets. But DeNiro’s performance as Johnny Boy was just too powerful, earning him Best Supporting Actor Awards from the New York and National Society of Film Critics. He had taken viewers’ breath away, just like Johnny Boy’s line, “I f*ck you right where you breathe.”

Afterward, there was no question as to who would become the bigger star. DeNiro went on to do seven more with Scorsese in a phenomenal 22-year collaboration: Taxi Driver (1976), New York, New York (1977), Best Actor for Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1982), GoodFellas (1990), Cape Fear (1991) and Casino (1995). But Keitel remains a vital piece in the DeNiro’s development. As scholar David Thomson writes, “Harvey provoked Bobby, punched him, the way LaMotta helped define Ray Robinson’s greatness.” (C) The next time Scorsese paired the two in Taxi Driver, it was DeNiro in the lead and Keitel in support, with Travis Bickle delivering the gut punch to Keitel’s pimp.

![]()

Rock & Roll Director

The friendly rivalry between Keitel and DeNiro is best expressed in one of Scorsese’s most genius directorial moments, as he gives DeNiro the coolest entrance in all of movie history. As the camera dollies in slow motion toward Keitel’s jealous eyes, we see his reaction to what’s walking through the door. DeNiro enters with a girl on each arm, strutting in slow motion to The Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” all in the enveloping red haze of a smoky bar.

This technique — a slow-mo shot of a pair of eyes set to a classic song — can be traced through Scorsese’s work, from “Sunshine of Your Love” as DeNiro decides to whack Morrie in Goodfellas (1990) to “Love is Strange” as DeNiro is first smitten with Sharon Stone in Casino (1995).

Dare I say no filmmaker has used popular rock ‘n roll hits more organically, more effectively or more prolifically than Scorsese. Scorsese’s soundtracks are inextricably tied to his images, such that Mean Streets has the soundtrack skip when a character is shoved into the jukebox. This rock ‘n roll auteur staple is apparent right from the opening credits, as The Ronnettes’ “Be My Baby” launches us into the opening credits, where Scorsese’s camera enters the light of a film projector, which shows “home movie” footage of the characters, then zooms into one of the clips to enter the movie. This technique both echoes Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) and foreshadows George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969).

Scorsese also makes impressive use of the long single-take, repeated later as Deniro approaches the boxing ring in Raging Bull (1980) and as Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco enter the Copacabana in GoodFellas (1990). In Mean Streets, we get a 69-second long-take with a hand-held camera that follows Johnny Boy through Charlie’s apartment and into the bedroom, then back out to Charlie out into the kitchen. We also get a 32-second single take, following three guys brawling around all corners of a pool hall, set to the oldies classic “Please Mr. Postman” in a counter-intuitive juxtaposition of upbeat song and violent action that later was used for the beating of Billy Batts in GoodFellas.

Perhaps my favorite technique in the entire film comes with a woozy close-up on Charlie’s inebriated face during a party, the camera tipping to the side as he passes out onto the floor. This technique has been repeated in everything from Bad Santa to Breaking Bad.

Still, Scorsese’s most masterful scene may be the love scene between Charlie and Teresa, where Charlie holds a finger gun toward Teresa as we hear the sound of a real gun blast, foreshadowing the finger gun at the end of Taxi Driver.

Another Mean Streets-Taxi Driver connection comes moments later, as Charlie watches a nude woman through parted fingers.

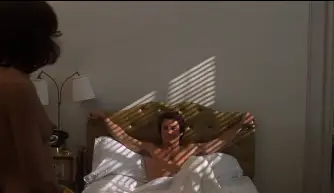

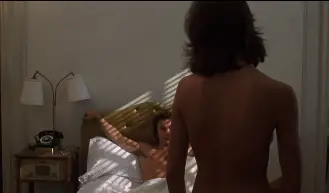

Also in this same scene, note how Charlie stretches his arms across the headboard to create crucifix imagery, as venetian blinds paint jail-bar shadows across him, the perfect visual for his internal contradiction, living a simultaneous life of crime and faith. It is also symbolic that a nude woman would block this crucifix image.

Every image matters, and Scorsese is always one step ahead of his characters, the omniscient “eye of God,” so to speak. And if we tap into this omniscient eye, we may see clues to what feel like “ambiguous” moments on first viewing. Note the symbolic foreshadowing of Johnny Boy lying on a tombstone.

![]()

Legacy

For all this, Mean Streets blew the critics away in 1973, as Newsweek said it “triumphantly heralds the arrival of director Martin Scorsese” and critic Pauline Kael called it “a true original and a triumph of personal filmmaking.” (B) Where does Mean Streets rank today? Sight & Sound magazine did not include it in its 2012 list, nor did the American Film Institute, which chose Raging Bull, Taxi Driver and GoodFellas instead. But the reputation of Mean Streets continues to grow, ranking No. 7 all-time in Entertainment Weekly’s 2013 list, a huge jump from its No. 64 spot in the magazine’s previous list.

Personally, I still think Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980) and GoodFellas (1990) are his three best works, showcasing a daring director at his peak of maturity. Others may prefer his more recent work — The Departed (2006), Shutter Island (2010) and Hugo (2011) — as more accessible entertainments. Compared to these, Mean Streets is a raw, gritty tragedy that favors character study over plot, atmosphere over structure and ambiguity over tidiness. As Scorsese said, “The film isn’t as small as Little Italy. Little Italy, for me, is, in a sense, a microcosm for something much much larger. If you wanna get really deep into it, it’s about life, it’s about people, it’s really based on certain character realities.” (A)

But even if you are one who favors story over character or theme, Mean Streets is a must watch, not only as the origin of other Catholic guilt films (The Exorcist, Saturday Night Fever, The Boondock Saints), but also as the seed of so many Scorsese flicks to follow. After all, Scorsese started out pursuing the priesthood, but decided his talents would be better applied to filmmaking, reaching his “salvation” with Raging Bull (1980).

This angst is was makes Mean Streets eternally fascinating, from his faith-debating narration in Charlie’s head, to the words “Martin Scorsese…director” under an image of Keitel shaking hands with a priest in the opening credits. This is auteur expression at its zenith, right down to the final shot of Scorsese’s own mother closing an apartment window, both closing the film and closing the window into Scorsese’s own childhood.

Which brings us back to the original double question. Where would movies be without Martin Scorsese? And where would Martin Scrosese be without Mean Streets? The master provides the answer in his own words:

“[Mean Streets] seems to, in my mind, be the final culmination of everything I was to do and who I am. And so in my mind it’s not really a film, it’s a kind of a declaration or statement of who I am and how I was living and those thoughts and dilemmas and conflicts that were very much a part of my life up until at that time. And they couldn’t be expressed any other way than by resulting in this movie. So I keep thinking about the film as the years go by because a lot of what’s said in the film was a sort of culmination of what I wanted to say at that point in my life. ‘Wanted to say’ is a bad phrase because it might be mistaken for having had a message to give to anybody. There’s no message. It’s just something that sort of came out of me organically.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Vintage documentary: Martin Scorsese: Back on the Block

CITE B: Mean Streets DVD cover

CITE C: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film