Director: Christopher Nolan

Producers: Jennifer Todd, Suzanne Todd (Remember, Newmarket, Todd)

Writers: Christopher Nolan (screenplay), Jonathan Nolan (short story)

Photography: Wally Pfister

Music: David Julyan

Cast: Guy Pearce, Carrie-Anne Moss, Joe Pantoliano, Mark Boone Junior, Russ Fega, Jorja Fox, Stephen Tobolowsky, Harriet Sansom Harris, Thomas Lennon, Callum Keith Rennie, Kimberly Campbell, Marianne Muellerleile, Larry Holden

![]()

Introduction

“Memory is unreliable. Memory’s not perfect. It’s not even that good. Ask the police. Eye-witness testimony is unreliable. Cops don’t catch a killer by sitting around remembering stuff. They collect facts, make notes and draw conclusions. Facts, not memories. That’s how you investigate. Look, memory can change the shape of a room, it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They’re just an interpretation; they’re not a record. And they’re irrelevant if you have the facts.”

There’s a point in Memento where the lead character asks his wife why she enjoys reading a particular novel more than once. “I always thought the pleasure of a book was wanting to know what happens next,” he says. Such is the very secret of Christopher Nolan’s master puzzle of a film, its ability to have us guessing what’s coming next narratively while already knowing what’s coming chronologically. We are kept simultaneously informed and uninformed, at the mercy of a film that moves largely in reverse order, drawing suspense out of discovering the truth of the past, rather than revelations of the future.

![]()

Plot Summary

In his biggest stage since the detective in L.A. Confidential (1997), Australian actor Guy Pearce plays Leonard, a clean-cut, sharp-suited man coping with a horrific event from the past. From the beginning, he describes the rape and murder of his wife, an attack that left him brain damaged with a rare condition called anterograde amnesia, a.k.a. short-term memory loss or the inability to form new memories. As he himself puts it, “He killed my wife and took away my f*ckin memory. He destroyed my ability to live.”

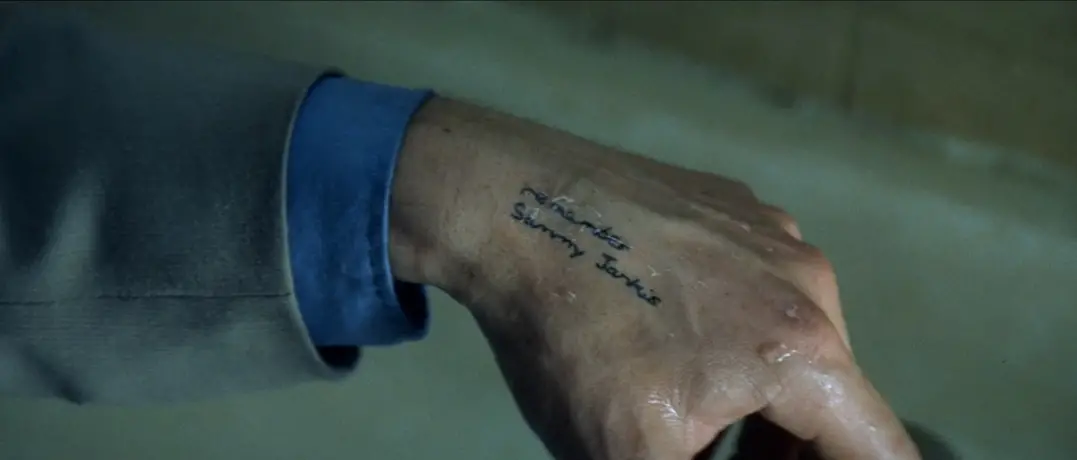

Lenny now has a new reason to live — to find and kill the culprit, a John Doe who’s name he believes begins with “John G.” But Lenny’s revenge does not come easy. He can only remember things that happened prior to the attack, so his every clue must be documented right away so that he doesn’t forget. Replacing his memories are a series of “mementos” — Polaroids, post-it notes and body tattoos, like the mirror-friendly phrase on his chest: “John G raped and murdered my wife.”

It’s an almost hopeless way to solve a murder, made more hopeless by those closest to him. Both his talkative sidekick, Teddy (Joe Pantoliano, The Fugitive, The Matrix), and his bartender/sex partner Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss, The Matrix), could just as easily be manipulating him as they could be helping him. He has no way of knowing — and neither do we.

It’s an almost hopeless way to solve a murder, made more hopeless by those closest to him. Both his talkative sidekick, Teddy (Joe Pantoliano, The Fugitive, The Matrix), and his bartender/sex partner Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss, The Matrix), could just as easily be manipulating him as they could be helping him. He has no way of knowing — and neither do we.

![]()

Screenplay Innovation

Written by Christopher Nolan, from his brother Jonathan’s short story Memento Mori, the Brothers Nolan tell the majority of their tale in reverse order, weaving the most innovative narrative structure since Pulp Fiction (1994), where Tarantino cleverly juggled his scenes, and Seinfeld, whose episode “The Betrayal” (1997) told its tale in reverse order. Of course, the fractured narrative dates all the way back to Griffith with Intolerance (1916), Welles with Citizen Kane (1941) and Wilder with Sunset Blvd. (1950), but Memento was the next brilliant step, beginning with the story’s end, ending with its middle and showing its beginning in a recurring B&W motel room sequence.

As the film progresses in this bizarre fashion, we witness scenes that end where the previous one began, allowing us to “forget” what happened chronologically before, simply because we haven’t seen it yet in the movie. As such, we experience each scene exactly as Leonard, making us sympathize with the protagonist’s condition all the more.

The innovative screenplay earned the Sundance screenwriting award, the AFI Screenwriter of the Year Award and an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay, losing to Gosford Park (2000). And yet, there are screenwriting traditionalists who dislike this breach of etiquette, particularly Blake Snyder, who wrote “Screw Memento” in his popular screenwriting book “Save the Cat,” which offers a “paint by number” approach with certain plot events on specific page numbers. While I highly recommend the book for budding screenwriters, Memento is one case where I respectfully say, “Screw your snide tone, Snyder.” The majority of screenwriters disagree with you, as the Writers Guild of America voted Memento one of the Top 101 Screenplays of All Time.

The brilliance of the script is not solely its concept of fractured plot structure. It also brilliantly emphasizes details within each scene. Each time jump is done with clever nuance, explaining why Leonard has a particular item in his hand, or revealing the cause of a man’s laughter in the scene before (think Elaine’s sneeze and Jerry’s “bless you” in the Seinfeld episode). In this way, the Nolans are able to mine humor by ending each scene with dialogue that began the scene before it, meshing the concepts of two 1993 flicks — the clever repetition of Groundhog Day (1993) and the wife murder mystery of The Fugitive (1993) — to create one exciting, complex beast.

![]()

Directing Style

Adding to the originality of the screenplay is Christopher Nolan’s directing style. Take for instance, the running black-and-white sequence of Leonard’s motel phone conversations. The reason for black-and-white was not to make these scenes drab and boring like the sepia Kansas in The Wizard of Oz (1939), nor was it to recapture the vintage feel of Jake LaMotta fights like Raging Bull (1980). Nolan’s choice for B&W is to separate them as the only chronological sequence in the film, allowing the reverse order to move in color.

The shifts from black-and-white to color are elevated by the stark cinematography of Wally Pfister and the Oscar-nominated editing of Dody Dorn. Note how Dorn intercuts flashes of his wife’s attack and even runs the opening scene in reverse. Overlaying it all is Nolan’s choice of tense score, a constant rumbling of ticking clocks and beating hearts, occasionally accompanied by Pearce’s nervy voiceover.

![]()

Pop Culture Echoes

Perhaps the biggest accomplishment by Team Nolan was the ability to make something so fresh from a subject matter that had been done to death. The “memory loss” idea was so played out at the time, from Suture (1993) to Spellbound, where Gregory Peck plays an amnesiac accused of murder in the Alfred Hitchcock classic. French director Alain Resnais was also obsessed with the notion of memory and explored it profoundly in everything form Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) to Last Year at Marienbad (1961).

But like these revolutionaries, Memento made the concept its own, influencing countless films to follow, from David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. (2001), where Naomi Watts battles amnesia to solve a puzzle, to Peter Segal’s 50 First Dates (2004), where Adam Sandler courts an amnesiac, to Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind (2004), where Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet erase a failed relationship from their memories. How fitting that Nolan would return to this theme in Inception (2010), where Leo DiCaprio plants dreams within dreams within dreams in a massive special effects extravaganza that never quite rises to the brilliant level of the low-budget Memento.

Its influence has also rippled outwardly into the world of technology, as researchers recently set up an Internet time machine to study how our internet data is saved. Its name? Memento.

![]()

Legacy

The film’s arrival left critics like Leonard, scrambling for notebooks to write stuff down before it escaped their brains. Rolling Stone critic Peter Travers called it “a new classic among thrillers,” and his peers overwhelmingly agreed with a 92% on Rotten Tomatoes.

The film also saw success on the mainstream side of the coin, earning $25 million at the box office and much more in home video — not bad for an indie flick that cost just $4 million to make. This phenomenon caused Entertainment Weekly to rank Memento the #13 Greatest Independent Film of All Time, writing:

“Christopher Nolan’s modestly budgeted sleeper hit managed to claw its way over the indie fence and into mainstream recognition on pure ingenuity. Before Memento, the ‘character with amnesia’ subgenre was, generally, a rather tired one (and has become so again since), but using the simplest of devices – telling the story’s episodic structure in reverse order – the filmmakers … forged a tale that was arse-clenchingly compelling, and ironically, unforgettable.”

The film has since racked up a powerful 8.5 on IMDB, tied with such classics as North By Northwest (1959), Apocalypse Now (1979) and Saving Private Ryan (1998). And while its rating is currently lower than Nolan’s Inception (8.8) and The Dark Knight (9.0), it remains his most fascinating piece of filmmaking. Expect it to rise even higher over time.

Which brings us full circle to Leonard’s question: why would his wife would want to read a novel to which she already knows the ending? The late Roger Ebert claimed Memento is a meal best eaten once, writing after a second viewing, “Greater understanding helped on the plot level, but didn’t enrich the viewing experience. Confusion is the state we are intended to be in,” while citing a “hole big enough to drive the entire plot through” — how does Lenny even remember that he has short-term memory loss? (A) Other questions persist in the unseen moments between his wife’s attack and the start of Lenny’s pursuit, but the twist ending joins The Usual Suspects (1995) and The Sixth Sense (1999) as powerful shockers that not only beg instant rewatch, but hold up on repeat viewings, inviting further contemplation and juicy conversation.

“Now, where was I?”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: RogerEbert.com, Review