Director: Tim Burton

Producers: Tim Burton, Denise Di Novi (Fox, Touchstone)

Writers: Tim Burton and Caroline Thompson (story), Caroline Thompson (screenplay)

Photography: Stefan Czapsky

Music: Danny Elfman

Cast: Johnny Depp, Winona Ryder, Dianne Wiest, Anthony Michael Hall, Kathy Baker, Vincent Price, Robert Oliveri, Conchata Ferrell, Caroline Aaron, Dick Anthony Williams, O-Lan Jones, Alan Arkin, Susan Blommaert, Linda Perri, John Davidson

![]()

Introduction

Few directors in our history, let alone the last 25 years, have such a distinct style that you can look at any of their films and within seconds identify who must be directing it. But after just one opening credit sequence, one Danny Elfman musical note, one off-kilter Johnny Depp performance or one dark or candy-colored land of imagination, and you can instantly say, “This is a Tim Burton film.” In this way, Burton may be one of the few auteurs we have going today (along with Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese), whose visual cues seem backed by a consistent world view, in Burton’s case, that of the neglected child.

Scholar David Thomson asks us to consider all the tortured childhood souls in Burton’s pictures: his debut animated short Vincent (1982) shows the “nightmarish inner life of an outwardly ordinary child;” Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (1985) follows an immature man who never grew up; Beetlejuice (1988) is “a rogue sprite, a kind of Peter Pan;” Edward Scissorhands is left incomplete by his Inventor father figure; and Batman Returns (1992) features a Penguin who was born so ugly, his parents sent him adrift in a basket through the sewers, a regular “Moses in Harry Lime Land.” (A) To Thomson’s list, I will add Batman (1989), whose hero is orphaned by the smoking gun of Nicholson’s Joker; Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), where Willy Wonka has created for himself a children’s fantasyland; and Sweeney Todd (2007), whose title character’s rough childhood has led to a life of London crime. (A)

The fact that Burton keeps coming back to this theme is ironic, considering he himself grew up in fancy Burbank, studied at the California Institute of the Arts and landed his first job as an animator at Disney. Somehow the opposite of his own life has become his on-screen wheelhouse. Perhaps Burton is reaching out in sadness to those viewers who missed the benefits of his own childhood, offering the saving grace of imagination, while pushing the importance of visual storytelling.

![]()

Plot Summary

Edward Scissorhands begins with a young girl asking her grandmother about the origin of snow, sparking a fascinating bedtime story, a la The Princess Bride (1987). Edward (Johnny Depp) is the incomplete creation of a wily old Inventor (the final film role of Vincent Price, whom Burton admired as a child in Monte Hellman films, then cast as narrator of his debut animated short Vincent). This Inventor has tried to turn a vegetable chopper into a human being, but before he can finish his creation, the Inventor dies, leaving Edward with a pair of scissors for hands and living alone in a dark mountain mansion. Everyday, Edward looks down from the mountain and sees the colorful suburban neighborhood below (a la The Grinch looking down on Whoville), wishing he could be a part of it. Until one day, the neighborhood comes to him.

Peg Boggs (Dianne Wiest) is an Avon lady with tons of neighborhood friends, but none of whom want to buy her products. Hard up for sales, she ignores “haunted rumors” and ventures into the derelict mansion, where she meets Edward and invites him to come stay with her. Naturally, this surprises her husband (Alan Arkin) and the rest of the neighborhood, who are fascinated by this new arrival into their cliched, routine lives.

Before long, Edward is a local celebrity, dazzling residents with his bush-trimming, pet-grooming and hair-cutting skills. But his popularity is only a product of his unique gift. These same neighbors fail to understand the real Edward, a scared, innocent figure thrust into an unknown culture. His only hope is Peg’s cheerleader daughter Kim (Winona Ryder), who connects with Edward thanks to his sincere devotion to her. This gets under the skin of her boyfriend Jim (Anthony Michael Hall), who turns the town against Edward, Frankenstein style, forcing the two lovers toward a tragic conclusion.

![]()

Sharp Cast

Would this story feel like magic or a shameless gimmick? Much of that would depend on the casting. The biggest star was Wiest, at the height of her career between two Woody Allen Oscar wins for Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and Bullets Over Broadway (1994). In casting the neighbor roles, Burton found a pair of future Emmy nominees in Conchata Ferrell (Two and a Half Men) and Kathy Baker (Picket Fences). As for the youth, Burton cleverly cast against type, choosing the goody-two-shoes Anthony Michael Hall (The Breakfast Club) to play the villain, and the more deviant Winona Ryder (Heathers) to play the nice girl. (C)

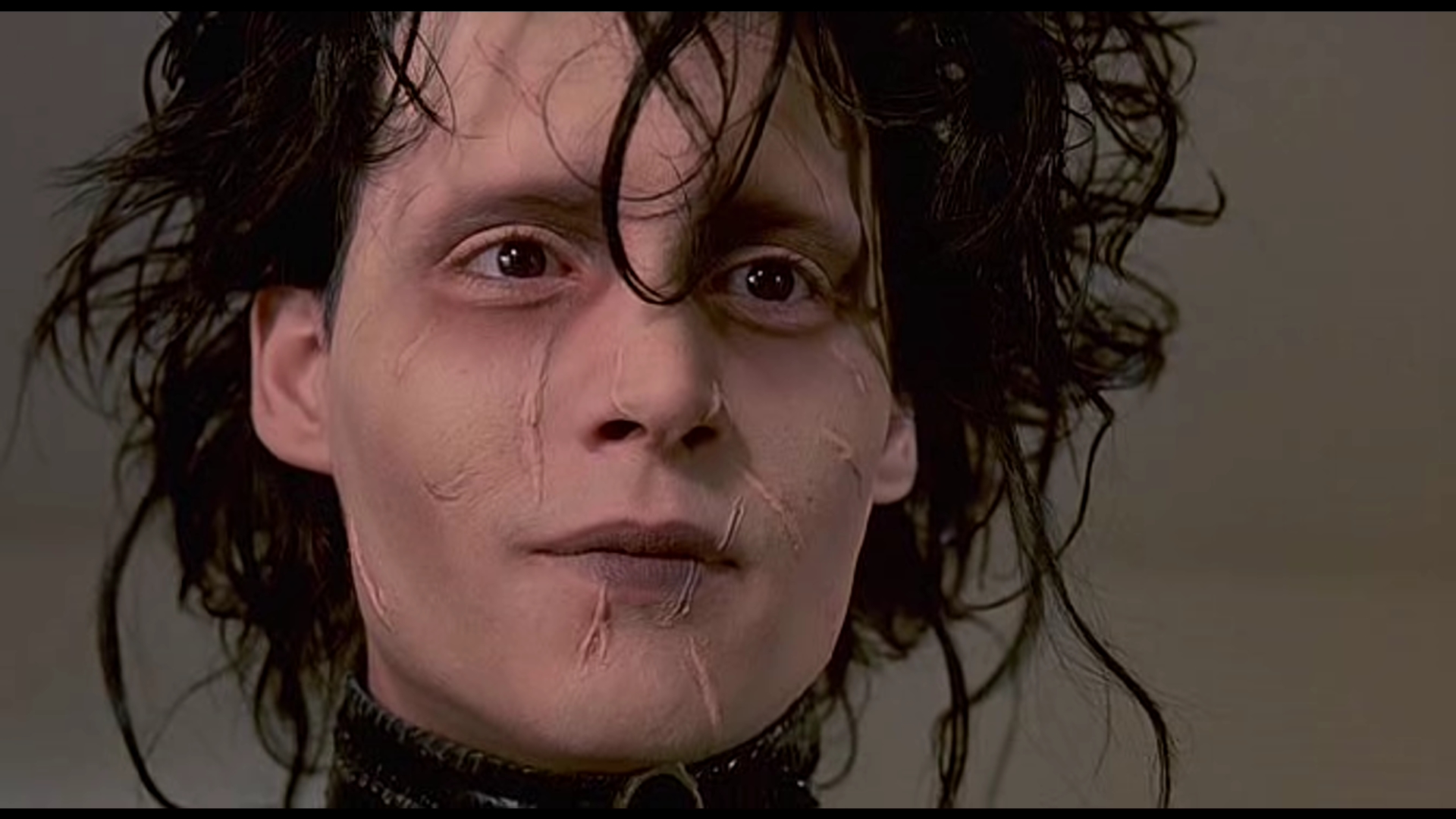

Still, the biggest find was the 27-year-old Johnny Depp, who was previously a TV teen idol on 21 Jump Street (1987) and a victim in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and Platoon (1986). Burton introduced Depp as a leading man, and the actor never forgot it, collaborating numerous times since: Ed Wood, Sleepy Hollow, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Corpse Bride, Sweeney Todd, Alice in Wonderland and Dark Shadows. But of all his great work, Edward Scissorhands rivals Captain Jack Sparrow as his most iconic. The role required equal parts Frankenstein, Quasimodo, and The Beast of Beauty and the Beast, and Depp created one for the ages, with his quiet voice, shy innocence, pure joy from topiary creations, and his E.T. shuffle when he’s done something wrong.![]()

Visual Splendor

Of course, Depp’s performance would have been nothing without the Oscar-nominated makeup of Ve Neill and Stan Winston, who gets the film’s coolest credit: “Special Makeup and Scissorhands Effects.” Those shears steal the show, but other make-up and wardrobe choices are also brilliant: the leather bondage gear he tries covering with a white button-up and black suspenders; the dark, frizzy hair sprouting all over the place; and the pale-white face, covered in self-made scars, accidentally cutting himself with his “hands.”

The visual splendor also extends into Edward’s surroundings, where we get two distinct worlds — (1) a dark, mechanical castle interior, and (2) a bright, candy-colored neighborhood, where pastel colors line the streets with blue, pink, yellow and green houses. It’s almost the stuff of Dr. Seuss.

If viewers were unaware of Burton’s animation background before Scissorhands, there would be no doubt after seeing this flick. Burton constructs the entire opening sequence using miniature models of both the castle and the neighborhood below.

![]()

Burton the Director

In a way, the film serves as a bridge between Burton’s animation and live-action know-how, as the camera begins in a live-action home, moves out through the window and dissolves into the miniature models the moment it reaches the backyard fence.

We see Burton experiment with the camera, finding tricky reflections in a driver-side car mirror, or a mirror inside a closet door. He also uses alternating zooms, on Ryder and on the TV, to express interior emotion. He offers meaningful “frames within the frame,” like shooting through a heart-shaped topiary bush. Most of all, Burton avoids a reliance on quick cutting, ironic for a film about scissor hands. Instead, he inhabits the physical space with the camera watching from a dark corner of the castle attic or a corner of Peg’s living room, showing a depth of the surroundings and the characters’ place in them.

More than anything, Burton masters his tone of tragic magic, born from the unlikely romance between a young cheerleader and her hideous outsider. Ryder’s slow-motion dancing in the snow chips of Edward’s ice sculpture angel will give you goosebumps, and few movie moments are more beautifully tragic than Ryder saying, “Hold me,” and Depp responding, “I can’t.”

This is a character who wants so bad to touch those he loves, but can’t because he’ll slice them. The tone has much to do with Danny Elfman, who had already composed a phenomenal trio of Burton scores in Pee-Wee, Beetlejuice and Batman. Still, the score for Edward Scissorhands is arguably Elfman’s best, a labyrinth musical journey which Burton said epitomizes his most personal film. (B)

![]()

Reaction & Legacy

Less enthusiastic was Twentieth Century Fox, which had hoped the film would become the next E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982) and were disappointed by the modest $56 million box office. Perhaps the “scissorhands” gimmick was too bizarre for most moviegoers, or that Burton was far less established as Spielberg at the time. Either way, the film grew as both a cult favorite and pop culture reference point, from kids mesmerized by its wonder, to twenty-somethings binge drinking to the game “Edward 40 Hands,”taping 40-ounce malt liquor bottles to their hands.

Critically, the film was a hit, carrying a 91% on Rotten Tomatoes. Roger Ebert was one of the few to give it a negative review, while most others echoed Rolling Stone‘s Peter Travers: “Edward Scissorhands isn’t perfect. It’s something better: pure magic.” (D) Scholar David Thomson calls it “not just Burton’s best work so far, but the film most suited to his inclinations.” (A) And when Entertainment Weekly named its 100 Best Movies of the Last 25 Years, Scissorhands ranked #15, ahead of Do the Right Thing (1989), The Lion King (1994) and Schindler’s List (1993). Movie history has spoken, and we’ve been running with scissors ever since.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, New Biogrpahical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: Nina Easton. “For Tim Burton, This One’s Personal”, Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on 12/10/2007.

CITE C: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE D: Peter Travers, Rolling Stone review