Director: Blake Edwards

Producer: Martin Jurow, Richard Shepherd

Writers: Truman Capote (novel), George Axelrod (screenplay)

Photography: Franz Planer

Music: Henry Mancini

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, George Peppard, Patricia Neal, Buddy Ebsen, Mickey Rooney, Martin Balsam, Jose Luis de Villalonga, John McGiver, Alan Reed, Dorothy Whitney

![]()

On multiple debate fronts — greatest chick flicks, landmarks in fashion history, Hollywood’s most beloved leading ladies — all discussion must pass through one iconic actress in one equally iconic film: Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. This is the true test of a movie classic, to be deemed important in such a wide array of historical influence. Sure, Breakfast at Tiffany’s delves unashamedly into melodrama and suffers from certain stereotypes and censorship restraints of its time. But the film, drawing from a source novel by Truman Capote, struck a chord in 1961 that hasn’t let up since.

Partial credit must be given to Capote, whose childhood became the Dill character in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962); whose career novel became Richard Brooks’ courtroom drama In Cold Blood (1967); and whose life became an Oscar-winning performance by Philip Seymour Hoffman in Capote (2005). Still, you could argue that Breakfast at Tiffany’s remains his most popular screen adaptation. The rest of the credit belongs to the storied team of Hepburn and costume designer Hubert de Givenchy, who also crafted her outfits in Sabrina (1954), Funny Face (1957), Love in the Afternoon (1957), Paris – When it Sizzles (1964) and culminating in the Best Picture winner My Fair Lady (1964).

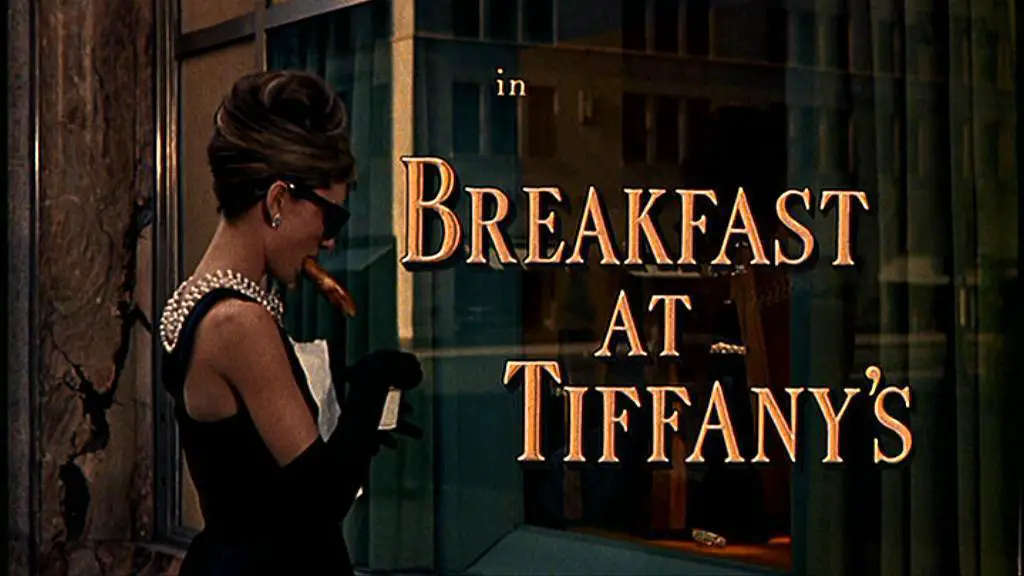

In Tiffany’s, Givenchy worked under the legendary supervision of Edith Head (Vertigo, Rear Window) to pioneer arguably the most famous look in 20th century fashion, Hepburn’s pin-up brunette hair, pulled into a tiara and streaked with blonde, atop an elegant black dress, complemented by a string of pearls, a pair of black shades and a longer-than-necessary cigarette holder. Yet no matter how stylish, the get-up required the proper human grace to stamp it into history. Hepburn was the right girl for the time, earning an Oscar nomination while defining the word “class” in her most memorable performance as an eccentric New York City socialite, aptly-named Holly Golightly.

Envisioned by Capote as a part for Marilyn Monroe, the extroverted Holly was an admittedly challenging role for the introverted Hepburn, who ironically never appeared more at home. The pretentious gold-digger hosts high society parties in attempt to land “the ninth richest man in America under 50,” and forces beaus to take her shopping at Tiffany’s, warning, “I don’t exactly know what we’ll find at Tiffany’s for under $10.”

Still, the film only hints at Holly’s main source of income: that she’s an actress-turned-call girl who accepts $50 to “take men into the powder room.” Perhaps Hollywood needed eight more years before it was ready to enter this realm in Midnight Cowboy (1969). Instead, Tiffany’s emphasizes Holly’s extra work carrying coded messages for a mob boss named Sally Tomato (Alan Reed).

Despite these questionable practices, Holly is an insanely likable character, certainly for her stunningly unique beauty, but more so for her enigmatic behavior. Her cat, appropriately named “Cat,” often sits in the sink. Her shoes are routinely stored in the refrigerator. And her mailbox is merely a space to house her perfume bottle. Part of the fun for viewers is to look for such oddities, however subtle, be it Hepburn shutting her dress in a taxi cab door, or keeping a caged bird, stuffed, in her apartment.

It’s these eccentricities that draw the attention of her upstairs neighbor, author Paul Varjak (George Peppard), who lives off the money of a wealthy heiress (Patricia Neal). Within this world of pretense, Holly and Paul collide in something that’s finally real: their love for one another. This is complicated by the fact that Paul falls for the authentic parts of Holly’s personality, rather than her public alibi of social status. What’s more, Holly remains indecisive on what she wants out of life, an existential crisis that is the crux of the film. As explained in a plot twist by Buddy Ebsen (The Beverly Hillbillies), Holly is no high society girl; she’s barely removed from her country bumpkin roots.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s is thus a character study into an insecure woman running from her past, clinging to portions of it (like nicknaming Paul “Fred” after her brother), yet desperately seeking an ideal that may never exist for her. This is best explained at a party when Paul runs into O.J. Berman (Martin Balsam), the man who “discovered” Holly as an actress in California and who now offers a stern warning: “She’s a real phony. You know why? Because she honestly believes all this phony junk she believes in.”

First-time viewers may struggle to sort out these themes, asking, “Why is the film called Breakfast at Tiffany’s? The only time she’s there is eating a pastry and drinking a coffee outside the window during the opening credits!” This sort of confusion is likely the product of modern Hollywood, which likes to spoon feed answers to audiences. Today’s viewers may also take issue with the film’s outdated social sensibility, particularly the white Mickey Rooney playing Holly’s buck-toothed Japanese neighbor. Today, this rings like a ridiculous stereotype that even Edwards says he wishes he could change, but alas, some things are trapped in the mindset of the early ’60s. On that note, Edwards has also expressed a dissatisfaction with the casting of Peppard, who would go on to star in TV’s The A-Team (1983). (A)

Despite these flaws, Edwards maintains a consistent tone toward his New York atmosphere. He remains a lesser-known director in the annals of film history, rarely recognized before his Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy in 2004. But throughout his work, Edwards demonstrated a unique knack for comedy, from Operation Petticoat (1959) to The Pink Panther (1963), as well as a distinct penchant for romance, as in Days of Wine and Roses (1962). The former is best on display during a party sequence where he allows his extras to improvise a number of funny antics.

The latter ability scores the biggest in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, as Edwards successfully mines the Holly-Paul relationship for three of the film’s most famous scenes. The first comes as Hepburn strums a guitar out on the fire escape while singing the popular Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer tune “Moon River,” a song that won an Oscar for Best Original Song, recurs instrumentally throughout film (winning Mancini another Oscar for Best Score), and was ranked the AFI’s #4 Greatest Movie Song of All Time, behind only “Over the Rainbow,” “As Time Goes By” and “Singin’ in the Rain.”

The second comes as Hepburn and Peppard “steal for the thrill,” donning masks in a scene highly influential on Matt Damon and Minnie Driver in Good Will Hunting (1997).

The third comes in a Hollywood happy ending which compromises the original Capote ending by bringing Hepburn and Peppard together to kiss in the rain.

While this scene resonates for the romantic imagery of rain-soaked lips, it works because of its setup in the preceding taxi ride. This scene, coupled with the opening shot at Tiffany & Co., is the key to the film, as Peppard breaks down Holly’s misguided ambition: “You call yourself a free spirit, a wild thing, and you’re terrified somebody’s gonna stick you in a cage. Well baby, you’re already in that cage. You built it yourself. And it’s not bounded on the west by Tulip, Texas, or on the east by Somali land, it’s wherever you go. Because no matter where you run, you just end up running into yourself.”

Any generation can relate to this theme, and the film will remain relevant as long as there are country girls faking it in the big city, eating pastries outside jewelry store windows, being knocked back down to size, befpre confiding in the unconditional love of a “Huckleberry friend.” The pop culture remnants show in everything from Breakfast at Tiffany’s slot machines where you pet the Cat for bonus points, to the fashion industry phrase, “That’s so Audrey,” to the ’90s pop hit by Deep Blue Something. The lyrics of the song speak to the cross-generational appeal of new lovers embracing an old movie romance: “I said what about Breakfast at Tiffany’s. She said I think I remember the film. Yes I recall I think we both kinda liked it. And I said well that’s one thing we’ve got.” (B)

If you still doubt the film’s importance, just ask its star, who was voted the #3 Greatest Actress of All Time by the AFI. Hepburn always considered it her most famous role. She’s forever linked with it, just as she is forever linked with class, elegance, New York City and all that her character falsely idealized but which she as an actress innately possessed. Her persona would become so linked with the film that in 1987, Tiffany & Co. would ask her to write the forward to its 150th Anniversary book. In it, her words could just as easily describe her own career, if you simply replace “Tiffany’s” with “Hepburn”:

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever, that is why the lustre of the art of [Hepburn] remains undimmed. [Her] name has stood for beauty, style, quality and constancy, [she] has brightened our faces … illuminated our homes … given distinction to our lives … class doesn’t age!” (C)

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Breakfast at Tiffany’s Anniversary Edition DVD, featurette “The Making of a Classic”

CITE B: Breakfast at Tiffany’s Anniversary Edition DVD, featurette “It’s So Audrey: A Style Icon”

CITE C: Breakfast at Tiffany’s Anniversary Edition DVD, featurette “Audrey’s Letter to Tiffany”