Director: Martin Scorsese

Producers: Julia Phillips and Michael Phillips

Writers: Paul Schrader (screenplay)

Photography: Michael Chapman

Music: Bernard Herrmann

Cast: Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Cybill Shepherd, Harvey Keitel, Peter Boyle, Albert Brooks, Leonard Harris, Frank Adu, Victor Argo, Gino Ardito, Garth Avery, Harry Cohn, Martin Scorsese

![]()

While Mean Streets (1973), Raging Bull (1980), GoodFellas (1990) and The Departed (2006) all dealt with some form of institutionalized American violence — organized by an established community of mobsters and fight bookies — Martin Scrosese used Taxi Driver to explore the opposite: the violence made possible by the lack of community, extreme isolation and a dangerous loneliness. In this case, it’s a 1970s New York City cab driver, a man who gives rides to countless people each night, but who remains utterly alone.

The taxi proved a career vehicle for Robert DeNiro, who was fresh off a Supporting Actor Oscar win for The Godfather Part II (1974), the same year Scorsese directed Ellen Burstyn to her own Oscar for Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) — a follow-up to her lead role in The Exorcist (1973). And so, three years after collaborating on Mean Streets, Scorsese and DeNiro reunited for DeNiro’s most harrowing performance: that of alienated Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle, whose cab meter might as well be a ticking time bomb.

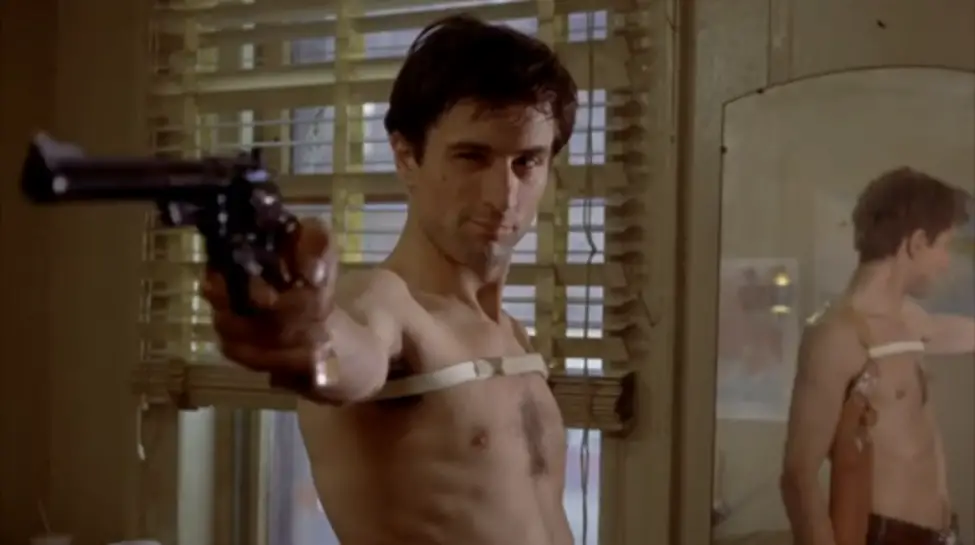

In just four improvised words — “You talkin’ to me?” — DeNiro was an instant legend, inventing a standard phrase in the English language and capturing the feeling of isolation crucial to Scorsese’s film. As Bickle stares into his apartment wall mirror, mumbling to himself and whipping out a newly-purchased handgun, we get a look at just what this character has become — a lonely creature lost in his own mind and in the claustrophobia of his own cramped existence. Are his urban surroundings the root of the problem, or is it the social outcast status offered to many a military vet? One thing is for certain: Bickle is one mentally disturbed individual, and Scorsese’s two-hour investigation into his life is one of the most fascinating, most complex character studies ever done.

Red flag: I said “character study,” a term that sends many casual viewers running for the exits. It’s true, Taxi Driver, may be hard for some casual viewers to fully appreciate. It’s deliberately slow, and like most Scorsese films, has no real plot to follow. Instead, viewers are simply left with a look into the life of one man, an insomniac turned moonlighting taxi driver, who speaks to viewers through the narration of his diary, written by Paul Schrader with a noir-like fire and brought to life by DeNiro’s monotone reading. Bickle’s rants are not unlike Dostoyevski’s “Underground Man,” and from it we learn how Bickle’s late-night taxi runs have stirred his hatred for his surroundings. (A)

TRAVIS BICKLE: “All the animals come out at night. Whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies, sick, venal. Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.”

Each time Bickle must clean his backseat of blood and other bodily fluids, he hates his situation even more, including a scene where Scorsese himself makes a cameo as a homicidal passenger staking out his cheating wife.

All the while, he reveals his own hypocrisy. Bickle is a “walking contradiction,” as the Kristofferson song in the film indicates. He attends porn theaters but watches with a hand over his eyes. He detests drug-use but pops pills in his cab. Whatever he tries to distance himself from, he is helplessly drawn to, and whatever he tries to obtain, he manages to push away, mainly any semblance of human contact (speaking to the same theme of Samuel Delany’s book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue).

His contradictory lifestyle leads him to confront society in three distinct ways throughout the film: rejoin it, destroy it, redeem it. He first tries to rejoin it by getting a job as a cab driver, shooting the shit with fellow cabbies (including Peter Boyle two years after Young Frankenstein and decades before TV’s Everybody Loves Raymond).

His next move is dating Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), a beautiful campaign worker (on staff with the always funny Albert Brooks).

Unfortunately, he scares her off by taking her to a porn theater on their first date, confusing sex for love (similar to Benjamin’s first date with Elaine in The Graduate).

Having been rejected in his attempt to rejoin society, he next tries to destroy it. He begins turning himself into a weapon, holding his hand over an intense flame and shaving his head into a mohawk. He buys a series of guns and knives, while designing his own home-made contraptions to better conceal and deliver his weapons into his hands.

This all leads to a plot to assassinate a popular presidential candidate, the one for whom Betsy campaigned. The notion is that killing him will somehow get her attention and make a name for himself. But this plot also fails, thanks to a suspicious Secret Service agent.

Having failed at rejoining and destroying society, Travis is left with no other alternative but to try to redeem it. He begins to obsess over the notion of saving a tweenage prostitute named Iris, played by a 14-year-old Jodie Foster in her first Oscar-nominated role, 12 years before winning for The Accused (1988) and 15 years before winning for The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

Intrigued by this little flower, Bickle follows her, like a crazy fan of the movie would later do to Foster in real life, and investigates her ties to head pimp “Sport” (Harvey Keitel).

Bickle sees the disturbingly young prostitute as his chance to do something worthwhile, writing in his notepad: “Here is a man who would not take it anymore”. He thus embarks on a bloody mission, killing Iris’ pimp (Keitel), then waging a climatic pimp-house massacre.

Viewers may leave the film torn on their loyalty to Bickle. Should we praise his vigilante justice? Or fear his disturbed state? Certain images — his head shaven into a mo-hawk; blood-dripping from fingers that form a gun blowing his own brains out; the final shot of his eyes darting quickly to his rearview mirror — leave a chilling impression on viewers. As it should. Bickle is an anti-hero, voted by the AFI the #30 Greatest Villain of All Time. How often is a villain the protagonist? This is what makes Taxi Driver highly unique, well ahead of its time in terms of the modern anti-hero.

No matter your take on Bickle’s morality, you must come to a unanimous decision on Scorsese as director: complete master. Visually, he captures New York as both a cultural hot spot and hell on earth — the colors of Times Square blurring through the taxi’s rain-soaked windows and reflecting in DeNiro’s glossy eyes; the haze of smoke billowing from steam-grates; the slow-motion shots of busy New Yorkers; and the use of such real-life locales as the Belmore Cafeteria on 28th Street and Park Avenue South, an 8th Avenue porno theater, Columbus Circle and the Garment District. (B)

In addition to the pure visual splendor, Scorsese’s camerawork was altogether groundbreaking, winning the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Note how we assume Bickle’s viewpoint, with a slow zoom into seltzer fizzing in a glass of water. And watch how Scorsese makes Bickle seem like a worthless pawn in an ancient world, allowing his camera to leave DeNiro and return to him in one long-take (see Bickle’s payphone conversation), or allowing DeNiro to exit the frame and, in the same shot, re-enter (see Bickle’s walk through the garage). This world exists without Bickle and runs according to fate, like the noir template which Taxi Driver so often flirts with in its hardboiled narration:

TRAVIS BICKLE: “I first saw her at Palantine Campaign headquarters at 63rd and Broadway. She was wearing a white dress. She appeared like an angel. Out of this filthy mess, she is alone. They… cannot… touch… her.”

If Schraeder’s narration isn’t noir enough for you, Bernard Herrmann’s jazzy score will knock you out. Cleverly, Scorsese abandons the rock-n-roll of Mean Streets in favor of Herrmann, knowing that such a film about watching from a taxi cab requires the same sound that would accompany a private eye, that which scholar David Thomson calls a “lament for impossible love.” (C) This lament rivals Herrmann’s haunting score for Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), with lonely characters driving around town, swapping San Francisco for New York City. In fact, Scorsese so admired Herrmann that when it came time to remake Cape Fear (1991), he revived Herrmann’s score from the 1962 original. The fact that Herrmann completed his Taxi Driver score just hours before dying in his sleep makes the film a powerful bookend to a musical journey that had begun with Citizen Kane (1941).

Most fascinating, and debate-provoking, is that most-weird overhead shot looking at the carnage of the film’s savage climax. As the camera rises up to clearly reveal the set below and journeys back down through the bloody hallways, we wonder if what we’re seeing is dream or reality. Is all that follows actually taking place? Is Bickle actually being received as a hero? Or are we merely seeing Bickle’s fantasy in his last dying thoughts? Scorsese never offers an explanation, but he doesn’t have to. After all, this is his fantasy, too. As Peter Boyle’s character tells Bickle, “You become what you are.” And in directing this film, Scorsese is the guy in the porno seats and Taxi Driver is playing on screen. He’s got his hands over his eyes, not wanting to see his hero killed, while leaving space between his fingers so he can see it happen.

Even with no clear conclusions, it’s a cab ride worth taking again and again. The movie fires on all cylinders, from Scorsese’s direction to Schrader’s screenplay, from Herrmann’s score to the deep cast — DeNiro, Foster, Keitel, Shepherd, Boyle, Brooks. Taxi Driver was nominated for four Academy Awards, but lost every one of them in a year dominated by Rocky, the fan-favorite which actually has Stallone repeat, “You talkin’ to me?” ‘

But Scorsese may have had the last laugh. In the AFI Top 100, Taxi Driver sits five spots ahead of Rocky. In the Sight & Sound international critics poll, Rocky is nowhere to be found, while Taxi Driver ranks 31st. It jumps all the way to No. 5 all time in the Sight & Sound directors poll, behind only Tokyo Story (1953), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Citizen Kane (1941) and 8 1/2 (1963). That’s how respected Martin Scorsese and Taxi Driver are among fellow directors, who continue to reference it in their own films, from Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) to Jim Jarmush’s Night on Earth (1991) to Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004). Taxi Driver may be the closest he ever came to perfection, joining Raging Bull as his two greatest art masterpieces. Who knows? Maybe someday a real rain will come and wash all the scum off best lists and leave only Travis.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE B: Taxi Driver DVD

CITE C: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film