Director: Martin Scorsese

Producers: Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff (United Artists)

Writers: Jake LaMotta, Joseph Carter and Peter Savage (book), Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin (screenplay)

Photography: Michael Chapman

Music: Pietro Mascagni

Cast: Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, Cathy Moriarty, Frank Vincent

![]()

Introduction

Certain filmographies wouldn’t be the same if not in tandem. Capra and Stewart. Ford and Wayne. Fellini and Mastroianni. Bergman and Von Sydow. And for 22 glorious years, Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro. Mean Streets (1973) put them both on the map. Taxi Driver (1976) cemented them as geniuses. And GoodFellas (1990) made them legends. But of all of the Scorsese-De Niro collaborations, Raging Bull is, in the words of Steven Spielberg, “Marty’s masterpiece.” Not only is it the greatest sports biopic ever made, it quite literally saved Scorsese’s life.

In 1973, De Niro read the book Raging Bull: My Story, the autobiography of legendary middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta, while in Sicily playing Young Vito Corleone in The Godfather Part II (1974). (A) How fitting that when Adult Vito later arrived in New York’s Little Italy, he was shot at the fruit market with a sign of LaMotta in the background (talk about divine mise-en-scene). DeNiro immediately suggested the book to Scorsese, who like LaMotta, had seen success in his profession but was now battling personal demons. Not only was he depressed after the flop of New York, New York (1977), starring De Niro, Liza Minnelli and Sinatra’s legendary title song, he was also battling a cocaine addiction that hospitalized him after a near overdose. It was at this very rock bottom that De Niro visited him and insisted that he clean up his life and make Raging Bull. Upon reading the book, Scorsese felt a spiritual connection to LaMotta and decided he would make one last film. (C)

Thankfully for us, it wasn’t his last. But it was his most important, reviving Scorsese the Artist and redeeming Scorsese the Man. As such, Scorsese dedicates the film to his late professor Haig Manoogian with a New Testament verse about a sinner who “once was blind but now can see.” The closing quote is Scorsese’s admission to his audience, in the form of a “thank you” note to his teacher, that Raging Bull allowed him to achieve some sort of salvation. It also speaks to the real-life LaMotta and the revelation he went through upon seeing the film. The Hall of Fame fighter admitted that after seeing the movie he realized for the first time in his life how much of a jerk he had been.

![]()

Plot Summary

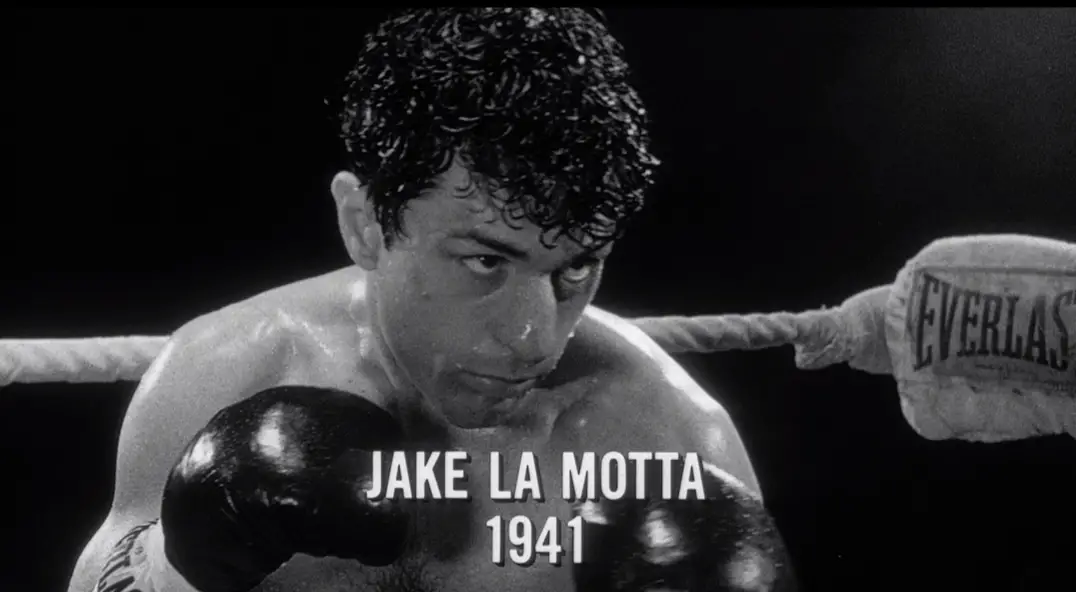

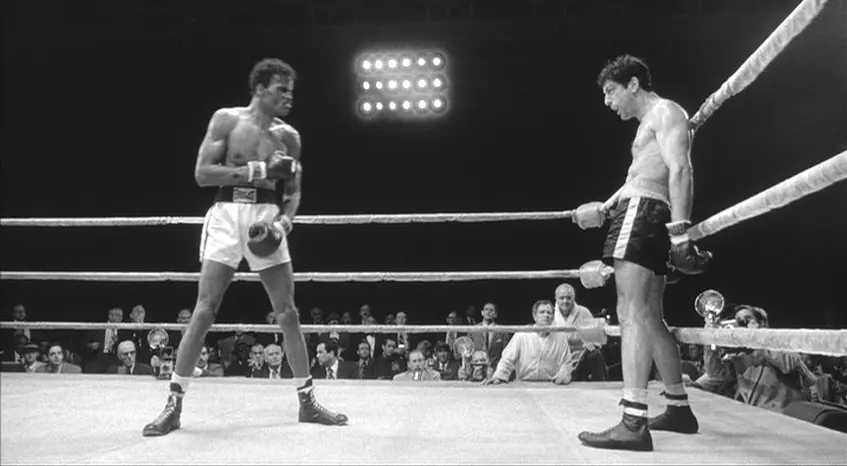

The story is less a “plot” as it is a “character study,” following New York City native Jake LaMotta (DeNiro) from 1941-1964. It chronicles his rise through professional boxing’s ranks, waging a legendary rivalry against arguably the greatest middleweight in history, Sugar Ray Robinson, whom LaMotta fought six memorable times.

Throughout his journey, he defaces opponents, regrets taking a dive, wins the championship belt, and loses it. All the while, he wishes his hands were bigger:

Throughout his journey, he defaces opponents, regrets taking a dive, wins the championship belt, and loses it. All the while, he wishes his hands were bigger:

- JAKE: What’s wrong with me? My hands.

- JOEY: Your hands? What about ’em?

- JAKE: I got these small hands. I got a little girl’s hands.

- JOEY: I got ’em too. What’s the difference?

- JAKE: You know what that means? No matter how big I get, no matter who I fight, no matter what I do, I ain’t never gonna fight Joe Louis.

- JOEY: Yeah, that’s right. He’s a heavyweight. You’re a middleweight. What of it?

- Jake: I ain’t ever gonna get a chance to fight the best there is. And you know somethin’? I’m better than him. I ain’t never gonna get a chance.

The “size of his hands” — visually achieved by constructing a larger than normal ice bucket — may actually be code for Jake’s impotence, which would explain his “raging” sexual frustration and give new meaning to the film’s title. While the violence in the ring is bloody, it’s nothing compared to the violence outside the ring, fueled by a sexual paranoia surrounding his wife Vicky (Cathy Moriarty), his brother Joey (Joe Pesci) and Joey’s Mafia friend Salvy (Frank Vincent).

Rather than a “feel good” rags-to-riches story like Rocky, which starts on a low and ends on a high, Raging Bull starts on a low, brings its hero to a high, then drops him back down to a self-destructive low. We slowly watch as he destroys his life and alienates everyone who loves him, to the point that he’s a fat owner of a cheap night club, telling bad jokes and smashing hits title belt to pieces to pawn the jewels. The film challenges us to feel for LaMotta, despite giving us every reason not to, asking viewers: what is your capacity to forgive?

![]()

Championship Performance

This intense character study rests on the shoulders of Robert De Niro’s tour-de-force performance. No other actor has been so endlessly compelling whilst being such a son of a bitch, filled with mistrust, paranoia and physical fury. We’re introduced to his misogynistic short temper in a dinner scene with his first wife:

We later get a glimpse at the depths of his paranoia while trying to fix the static of a living room television set. While asking his brother a series of personal questions, he convinces himself of things may or may not have happened.

Most impressive is the scene where LaMotta is locked in jail, punching and headbutting a wall, asking, “Why?” while telling himself, “You’re so stupid” and insisting, “They call me an animal. I’m not an animal! I’m not that bad.” You won’t find raw emotion more tragic than this.

It was his career performance, earning a second Oscar and his first as a leading man, after Best Supporting Actor for The Godfather Part II and Best Actor nominations for Taxi Driver (1976) and The Deer Hunter (1978). In preparation for the part, De Niro trained 1,000 rounds in the ring with the real-life LaMotta, shaping himself into a chiseled warrior. “Anytime he wants to quit acting, I could easily make him into a champion,” LaMotta said. “He’s that good.” (A)

After shooting the film’s fight sequences, De Niro packed on a then-record 60 pounds to portray a flabby, out-of-shape LaMotta in his decaying, post-fight days. Every actor who undergoes extreme physical transformations in hopes of bagging an Oscar can be traced to De Niro in Raging Bull.

This physical transformation brought “method acting” to a whole new level after it was pioneered by Marlon Brando (the other Vito). Fittingly, DeNiro recites Brando’s legendary monologue from On the Waterfront (1954) — “I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could been somebody” — while practicing his own act as a cheap nightclub owner. In doing so, screenwriter Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver) added a new legendary monologue to the cinema lexicon, an ode to every raging athlete who calms himself by shifting to entertainment:

JAKE LA MOTTA: “I remember those cheers, they still ring in my ears, and for years remain in my thoughts. Because one day I come to the ring and what happens? I forget to wear shorts. I recall every fall, every hook, every jab. The worst way a guy can get rid of his flab. As you know my life was a drab. And though I’d rather hear you cheer while I delve into Shakespeare, ‘A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse,’ I haven’t had a winner in six months. And though I’m no Olivier, if he fought Sugar Ray he would say that the thing ain’t the ring it’s the play. So give me a stage where this bull here can rage, and though I can fight, I’d much rather recite: ‘That’s Entertainment.'”

![]()

In DeNiro’s Corner

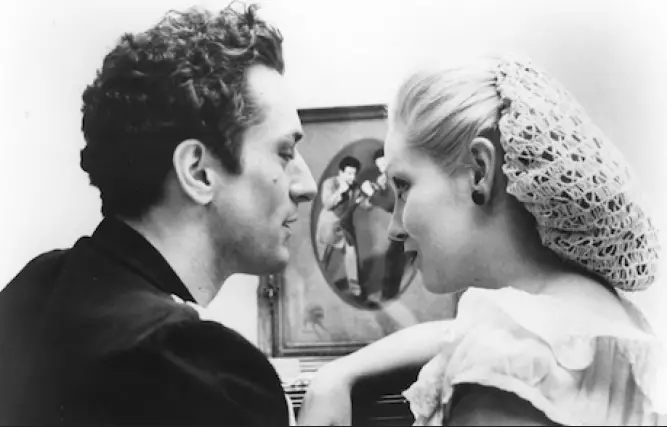

But DeNiro wasn’t the only crucial piece in building a masterpiece. Cathy Moriarty is one of the sexiest love interests put on black-and-white film, splashing in the pool in slow-motion, bending over to inspect a mini-golf windmill, sitting on Jake’s lap int he kitchen, and her nightgown showing a wet spot in the bedroom. She is also horrifically abused, interrogated each time she comes home, locking herself in the bathroom out of fear, taking a punch to the face, and portraying the complex “stand by your man” instincts of domestic violence.

Frank Vincent tops most movie foils as Salvy Batts, a last name that foreshadows his Billy Batts beatdown in GoodFellas, telling Pesci,“We were only having a few drinks,” a full decade before telling him, “Now go get your f*ckin’ shine box.” Poor Vincent. He gets destroyed by Pesci in both flicks.

Most importantly, Joe Pesci creates one of the best movie sidekicks in his breakthrough role. After a career of vaudeville acts, small film parts and band gigs (he once managed Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons), Pesci’s role as Joey LaMotta (Jake’s brother) launched him to stardom, allowing for roles across genres in Lethal Weapon 2 (1989), Home Alone (1990) and My Cousin Vinny (1992). But it was Raging Bull‘s Joey that gave him his first Oscar nomination and paved the way for the corrupt, fast-talking Italians he would later play in films like Once Upon a Time in America (1984), GoodFellas (1990) and Casino (1995), the middle of which won him the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.

![]()

Marty the Master Director

Poetic Violence. The above scene of Jake begging Joey to punch him cuts to the core of the entire movie: a sort of masochistic desire to prove one’s macho nature, likely covering up an insecurity about one’s own manhood. Scorsese was admittedly not a fan of boxing, and thus takes a stylized approach to the in-ring action. If violent masculinity ever came close to poetry it was in Raging Bull. So when Scorsese wrote the preface for director Sam Fuller’s autobiography, he might as well have been talking about his own films: “What you’re responding to is cinema at its very essence. Motion as emotion. Sam’s pictures move convulsively, violently. Just like life when it’s being lived with real passion.” (B)

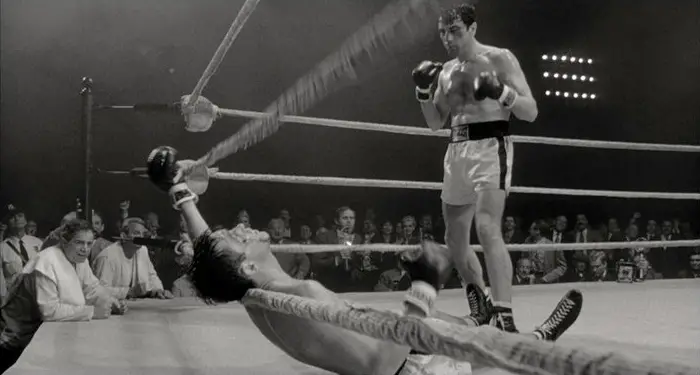

Scorsese’s lack of boxing knowledge actually allowed him to hone in on certain details that fight enthusiasts may have ignored. Rather than focus in on the winner of the climatic fight, the camera pans slowly to blood dripping off the ropes. Scorsese seems to say that these modern-day gladiators have just thrilled the fans, but at what price?

Black & White. After the success of Rocky (1976), nine other boxing movies were set to come out in 1980, so Scorsese said he wanted to make his film stand out. The best way to do this was to shoot in black-and-white, which also helped mask the bright red color of the boxing gloves and create a dark blood splatter similar to Psycho (1960), as opposed to the bright red gushers of Freddy Kreuger. The choice also realistically recreated the real LaMotta fights from the ’40s and ’50s, joining Schindler’s List (1993) as the best black-and-white films of the last 40 years. We almost forget we’re watching black-and-white until Scorsese provides a series of color images in a “home movie” montage.

Progression. Scorsese is up to much more than simply recreating black-and-white boxing images. The size of the ring itself progresses to symbolize LaMotta’s career. In scenes where LaMotta has success, Scorsese would place him in a larger ring, showing the vast possibilities of his expanding career. When those opportunities begin to fade, the ring becomes smaller, seeming to close in on him.

Hell on Earth. Scorsese was the first director to predominantly place his camera inside the ring, rather than watching from far away like a spectator. Because of this up-close style, the fight sequences are a jolt to the senses with spewing blood, wobbly knees, popping flashbulbs, roaring crowds, crashing blows, broken noses and animalistic roars in the sound design. In one particular hellacious fight against Sugar Ray, Scorsese actually lit a fire beneath the camera, causing smoke to rise into the shot and images to be distorted by the heat. All these elements are pieced together by Scorsese’s longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, who won an Oscar for her “seamless” and “perfect” edits. (A)

Shifting Speeds & Vertigo Effects. One of Scorsese’s greatest techniques is shifting from normal speed to either slow-motion or fast-motion. Fast-motion is used in the first fight against Sugar Ray. As LaMotta knocks Sugar Ray down, the film is sped up to create a jagged, rapid descent as the fighter hits the canvas. Slow-motion is used in the final fight against Sugar Ray, as time literally stands still, every slows down, Sugar Ray prepares an assault, and then unleashes it in normal speed. During this same sequence, Scorsese employs “The Vertigo Effect,” where the camera dollies out while zooming in, creating the illusion that the image is detaching from itself. See if you can notice it:

Single-Take. While the rapid in-ring action puts us in the boxer’s brutal shoes, Scorsese also knows when to use longer takes to let us experience the arena entrance. The best shot in the entire film is a 94-second singletake, which starts on De Niro warming up in the locker room, then follows him (without cuts) through the arena hallways, out of the tunnel, down through the crowd and into the ring, as the cameraman steps onto a crane to rise above the ropes. To me, the shot rivals even the Copacabana single-take in GoodFellas.

Mise-En-Scene. Outside the ring, Scorsese remains a master of mise-en-scene (i.e. the symbolic placement of all elements in the frame). Note how a photo of brother Joey sits between Jake and Vicky, foreshadowing how he will ultimately come between them.

Foreshadowing in Familiar Image. Elsewhere outside the ring, Scorsese uses familiar image to foreshadow violence. During the scene where Jake and Joey are trying to fix the static of a television set, note how Scorsese lingers on the staircase as Vicky arrives home and heads upstairs. Rather than cut away, the camera holds on these stairs, then pans slowly back to Jake’s paranoid eyes, a preview of violent coming attractions.

Ray of Hope. While most folks talk of Jake’s famous line, “You never got me down, Ray,” I choose to focus on the “ray of hope.” After Jake pounds the prison wall and collapses into tears in the darkness, we see his shoulder in a sliver of symbolic light. This image alone offers hope for LaMotta’s redemption and visually expresses Scorsese’s final Biblical quote about “once was blind, but now I see.”

![]()

Soundtrack

While Raging Bull stands out for its black-and-white cinematography, it also stands out for its distinct lack of a wall-to-wall rock ‘n roll soundtrack. Instead, Scorsese uses the instrumental music of Pietro Mascagni, an Italian composer whom Scorsese had heard growing up. It’s the perfect choice. Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana” will bring tears to your eyes with violins that cut straight to the soul during the slow-mo opening credits. The same piece was later used by Coppola in The Godfather Part III (1990).

![]()

Reaction & Legacy

The very fact that an Italian opera accompanies the entire film should tell first-time viewers something. The pace of the film feels very European, rather than something out of Hollywood. For the very same reason that 1976 fans embraced Rocky, they rejected Raging Bull upon its release. The film was the anti-Rocky, the only similarities being that the story was about an Italian-American boxer, produced by Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler. The theme of violent self-destruction was not nearly as appealing to the masses, so while Rocky was the highest grossing film of 1976, Raging Bull grossed just $23 million, compared to the $209 million of The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Academy voters reacted in much the same way, as Scorsese was so far ahead of his time. While Rocky won Best Picture and Best Director in 1976, Raging Bull lost both statues to Robert Redford’s family drama Ordinary People (1980) in one of the biggest mistakes in Oscar history. Ordinary People was a fabulous film, fabulously acted, superbly directed by Redford and with one of the greatest scripts ever written. But Scorsese’s direction here was groundbreaking, with Raging Bull belonging in the top dozen greatest films of all time.

Today, the dust has settled in Raging Bull‘s favor. On the American Film Institute’s Top 100 Films, Scorsese’s masterpiece jumped from No. 24 in 1997, all the way to No. 4 in 2007. When Sight & Sound polled directors around the world in 2012, Raging Bull ranked No. 12, ahead of Bergman’s Persona (1966) and Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959). American Film magazine poll named Raging Bull the Best Film of the ’80s. And when it came time for Peter Biskind to pen his book about the Hollywood Renaissance, as inspired by the French New Wave, he fittingly called it Easy Riders & Raging Bulls: How the Sex, Drugs and Rock & Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.

In a way, Raging Bull was the end of an era where Hollywood movie stars appeared in powerful pictures that rivaled even the high-brow art of European Palme d’Or winners. When the heavyweights of Spielberg, Lucas and Zemeckis era claimed the box office crown, a noticeable shift began. These guys knew their movie history and craft, but the generation that idolized them often did not. Similar to the decline of actual professional boxing, the “sweet science” of filmmaking was ignored. Big tent-pole events were promoted with huge box office purses to win, but Hollywood studios “took a dive” for the easy money. And so raging critics and daring filmmakers continue to screen Marty’s masterpiece, pounding their fists against the American wall, shouting Jake’s tragic cry for the rest of the world to hear: “Why? Why? Why?!? We’re not that bad!”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Raging Bull DVD booklet

CITE B: Scorsese’s introduction to the book A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking by Samuel Fuller, Christa Lang Fuller and Jerome Henry Rudes, 2002, Random House

CITE C: AFI 10 Top 10 countdown, CBS