Director: Robert Clouse

Producers: Raymond Chow, Paul M. Heller, Bruce Lee, Fred Weintraub (Concord, Sequoia, Warner Bros.)

Writer: Michael Allin (screenplay)

Photography: Gil Hubbs

Music: Lalo Schifrin

Cast: Bruce Lee, John Saxon, Kien Shih, Jim Kelly, Ahna Capri, Robert Wall, Angela Mao, Bolo Yeung, Betty Chung, Geoffrey Weeks, Peter Archer, Ho Lee Yan, Marlene Clark, Allan Kent, William Keller, Jackie Chan

![]()

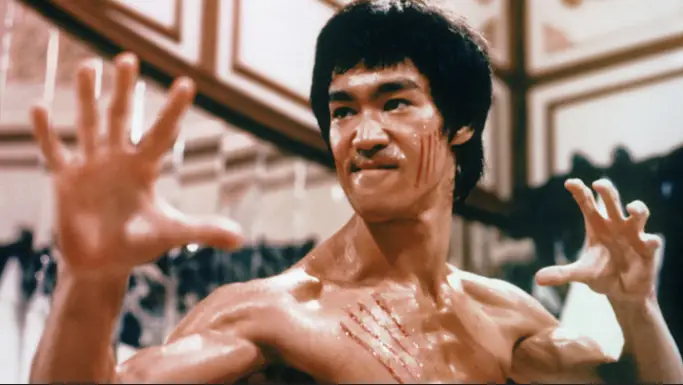

“A good fight should be like a small play, but played seriously,” Bruce Lee once said. “A good martial artist does not become tense, but ready, not thinking, yet not dreaming, ready for whatever may come. When the opponent expands, I contract. When he contracts, I expand. And when there is an opportunity, I do not hit. [My fist] hits all by itself.”

Is there a performer more tied to a specific art form or athletic discipline than Bruce Lee and martial arts? Is he not equal to Pele, Ali, Jordan, Elvis, Mozart, Fosse, Pavarotti, Liberace, Picasso, Dickens and Houdini in this regard? And just like Jordan, hand hanging in mid-air after hitting the game winner in the NBA Finals, Lee’s last film was his greatest.

Enter the Dragon was billed as “the first American produced martial arts spectacular,” introducing The States to the “chop-sockie” phenomenon that made Lee a superstar in Hong Kong, starting at age six with The Birth of Mankind (1946) and exploding with action hits like Fists of Fury (1971).

Granted, Lee was no stranger to America. He was born in San Francisco and had appeared on American television fas the sidekick Kato in The Green Hornet (1966-67), a character he would also lend to several episodes of Batman (1966). But Enter the Dragon was America’s first glimpse of the mythic movie Lee, and tragically our last, as Lee died of a brain seizure shortly before the film’s release. This “first and last” dichotomy created the perfect storm for icon status. We had another James Dean on our hands, only this one knew kung fu.

The plot goes a little something like this, that is, if you even care about a plot in such a movie. An expert martial artist named Lee (Bruce Lee) trains under the monks of the Shaolin Temple, where he is taught to honor Shaolin Commandment No. 13: “A martial artist has to take responsibility for himself and accept the consequences of his own doing.” But such codes are easily misused and perverted, and one man in particular, Han (Kien Shih), has turned to evil deeds, disgracing the entire Temple. Han has bought a Pacific island and turned it into a fortress for his own version of martial arts. His only contact with the outside world is a martial arts tournament, funded by a massive drug trade.

It’s this remote location that Lee is instructed to infiltrate as a secret agent, under the guise of competing in the tournament, but really looking for evidence of Han’s drug dealings. Of course, Lee has some personal stakes in the mission, seeing as three years earlier, Han’s men, including towering bodyguard Oharra (Robert Wall), came into town and bullied Lee’s sister to take her own life. As Lee dominates the tournament by day, he fights his way through the halls of Han’s fortress by night, building to a dramatic showdown with Han himself.

The plot is as contrived and predictable, at times seeming like something out of a James Bond flick — secret agent man infiltrates the island of a Dr. No-like villain who pets a white cat and rotates the type of fixture he will screw on as a replacement hand. But let’s face it. The story succeeds in its basic function: to provide an ass-kicking vehicle for Lee, who proves he’s undoubtedly one of history’s most charismatic performers. Yes, his heavily-accented readings of “Charlie Chan” dialogue are slightly exploitative. (B) But his “art of fighting without fighting” is shamelessly charming, and his wailing kung fu attacks are as addicting and imitable as anything ever put on screen.

Though small in stature, Lee is a magnificent physical specimen, flexing his six-pack abs, ripped pecs and chiseled arms with each punch. Never before or since have we seen an athlete so in control of his body, moving so fluidly through space. We should remember that there is no CGI or wire-fu assistance here (i.e. the impressive Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). This is all Lee, doing real physical motions. His greatest achievement is convincing us that he’s actually hitting his opponents, when he’s really pulling back just enough that he never strikes his fellow stuntmen, including a young Jackie Chan, getting his neck snapped at the 1:21:30 mark. Ironically, the same musical composer, Lalo Schifrin (Bullit, Dirty Harry), scored Chan in Rush Hour (1998).

Enter the Dragon boasts its own sort of physical poetry, as Lee weilds escrima sticks and swings nun-chucks. Luckily for us, we have more than a front row seat. Director Robert Clouse wants us in on the action, providing POV shots of the fighters in action, or a shard of glass about to jab into the camera lens. We most enter the dragon’s shoes during the “Hall of Mirrors” climax, when Lee enters Han’s secret chamber of 8,000 mirrors, and we are just as helpless in telling which reflections of Han are the real ones. It’s no Orson Welles in The Lady from Shanghai (1948), but it’s still damn entertaining. This final battle includes cinematographer Gil Hubbs’ favorite shot: the villain slain, feet off the ground, spinning round in round in this castle of mirrors. (A) By the time Lee exits this mirrored space, it’s easy to see why Entertainment Weekly voted it the #15 greatest action film of all time.

Still, for all those who relish in Lee’s chop sockie, there are just as many who dislike it, not the movies themselves, but what they stand for. There’s a school of thought, mostly in the academic world, that says such thin-plotted, beat-em-up efforts take cinema in the exact opposite direction of where it should be going. In other words, these films breed a mindset that echoes Lee’s famous quote — “Don’t think, feeel!” — asking viewers not to think during a movie or consider the cinematic language, but rather to passively sit and blindly feel the superficiality of the action. This is indeed a slippery slope, but true film buffs should be able to flip the switch and distinguish a film like Enter the Dragon from Citizen Kane, to be able to appreciate both, but for vastly different reasons.

When Enter the Dragon appears on best lists — the AMC Filmsite Top 300, the National Society of Film Critics Top 100, 97% Rotten Tomatoes, the National Film Registry — it’s not as a masterpiece of cinematic language, but as essential pop culture. Best lists like to cover their bases, and action films hold a key position in the cinema ballpark, even if they’re a designated hitter, packing a punch and putting buts in the seats but lacking the grace and technique to play the field. In other words, listmakers try to balance the academic greats with cultural phenomenons of historical importance.

Try naming another film that’s more influenced martial arts entertainment. Without Enter the Dragon, would there be the Wachowskis and The Matrix (1999), Tarantino and Kill Bill (2003), John Woo and The Killer (1989), Ang Lee and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)? Would there be Chow Yun-Fat and Jackie Chan? Jet Li and Lucy Liu? Chuck Norris and John Claude Van Dam? Would there be Bloodsport (1988) and Rush Hour (1998)? The Karate Kid (1984), 3 Ninjas (1992) or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990)? In video games, would Mortal Kombat‘s Liu Kang or Street Fighter‘s Fei Long have the same move sets? And would Nintendo’s Double Dragon have the same title, two lead characters named Lee and others named Williams, Roper, Oharra and Bolo?

The answer to all these questions is no. Bruce Lee mainstreamed it all, and Enter the Dragon made martial arts an international craze. Perhaps the biggest testament to this young man’s influence, despite only living to be 32, was the fact that Chuck Norris, Steve McQueen, James Coburn and George Lazenby all served as pallbearers at his funeral.

Lee’s untimely death no doubt drove his cult following, as rumors flew over the death of this seemingly healthy man. Speculation of a “Lee Curse” only grew with the tragic death of his son. Exactly 20 years after the death of Bruce Lee, 20-year-old Brandon Lee was killed on the set of The Crow (1994) when live ammunition was accidentally fired into his abdomen instead of blank rounds. Their true death stories are full of tragedy and intrigue, and have come to rival even the best of urban legend. It’s in this realm that Enter the Dragon finds its most lasting appeal, one final glimpse at a man who just missed becoming a legend in his own time and more than achieved it after his death.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: DVD audio commentary

CITE B: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die