Director: Stanley Kubrick

Producer: Stanley Kubrick (Natant, Warner Bros.)

Writers: Gustav Hasford (novel), Gustav Hasford, Michael Herr, Stanley Kubrick (screenplay)

Photography: Douglas Milsome

Music: Vivian Kubrick

Cast: R. Lee Ermey, Matthew Modine, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D’Onofrio, Dorian Harewood, Arliss Howard, Kevyn Major Howard, Ed O’Ross, John Terry, Kieron Jecchinis, Bruce Boa, Kirk Taylor, Jon Stafford, Tim Colceri, Ian Tyler

![]()

“How can you shoot women and children?”

“Easy, you just don’t lead ’em so much.”

Few lines sum up a film better than those from Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. It’s a stinging take on familiar territory, following a similar plot as Sidney Furie’s The Boys in Company C (1978) and borrowing much from Kubrick’s own work: the battle scenes of Paths of Glory (1957), the training sequence of Spartacus (1960), the absurd war commentary of Dr. Strangelove (1964), the evolution of man to machine of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the brainwashing effect of A Clockwork Orange (1971) and the possessed death stare of The Shining (1980). By the time Full Metal Jacket arrived, audiences had seen a decade of anti-Vietnam films: Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978), Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) and Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986). Still, Kubrick’s gem entered further into our pop culture with each passing reference, particularly the rifle creeds, blanket parties and night-burning fires of Sam Mendes’ Jarhead (2005).

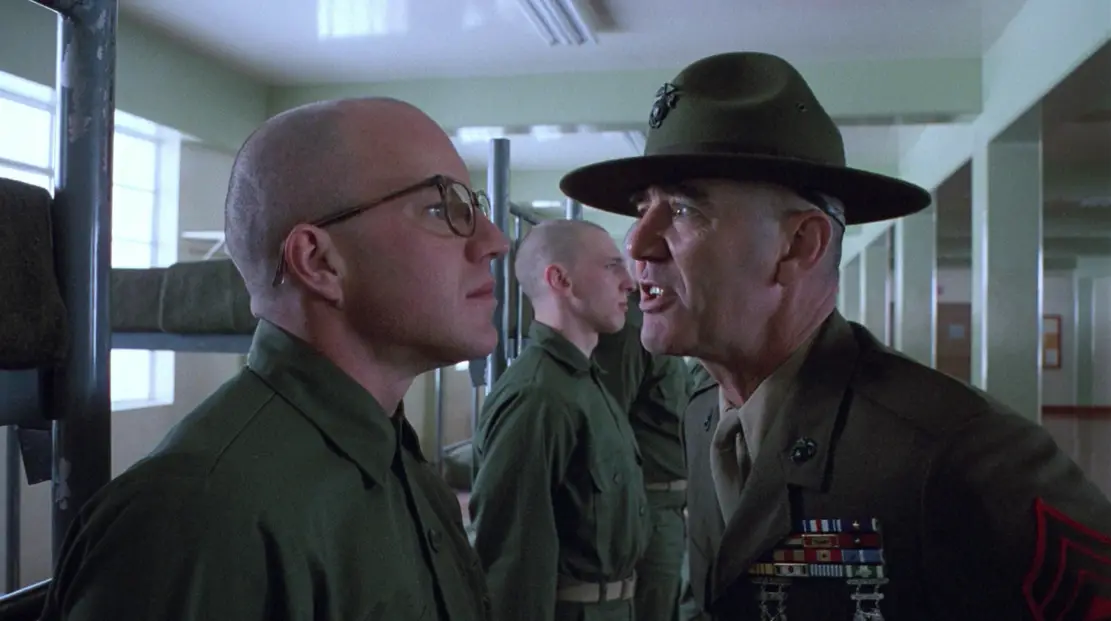

Based on the novel The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford, Full Metal Jacket follows a group of marine recruits from basic training to battle action in Vietnam. Opening with an extended boot camp introduction on Parris Island, the young men are broken down and whipped into shape by Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey), who gives each a rifle and a new name — Private Joker (Matthew Modine), Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), Eightball (Dorian Harewood), Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard), Cowboy (Arliss Howard) and Gomer Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio).

A chubby, mentally challenged kid, Pyle is the one whom Hartman rides the most, and the first to transform into a trained killer. The great irony is the subject of his first kill, horrifically snapping in a scene that announces the film’s title. After this shocking turn, we pivot to follow Private Joker, who becomes a war correspondent accompanying the rest of the men into the field, culminating with a bloody sniper battle in the streets of 1968 Hue.

The screenplay is in the best of hands, written by Hasford, Kubrick and Michael Herr, the latter of whom had written the voiceover narration for Martin Sheen’s character in Apocalypse Now (1979). The script earned the film’s sole Oscar nomination, no doubt thanks to its snappy, profane dialogue, introducing phrases into our collective vernacular, like a Vietnamese hooker’s stereotypical sexual invite: “Me so horny. Love you long time.”

The most quotable dialogue, however, comes from Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, who for about 40 minutes spits the most inventive obscenities ever to fly from a movie character’s mouth:

GUNNERY SERGEANT HARTMAN: “You had best unf*ck yourself or I will unscrew your head and shit down your neck! … I’ll bet you’re the kind of guy that would f*ck a person in the ass and not even have the goddam common courtesy to give him a reach-around … It looks like the best part of you ran down the crack of your momma’s ass and ended up as a brain stain on the mattress … I bet you could suck a golf ball through a garden hose.”

These are no doubt the lines that earned Full Metal Jacket a No. 11 spot on Men’s Journal‘s 50 Best Guy Movies of All Time, exploiting the macho types who relish a drill sergeant calling his recruits a bunch of dirty “pukes.” The opening stretch is the quintessential “maggots” sequence in film history, owing much debt to the irreplaceable R. Lee Ermey.

A former drill instructor and honorary Gunnery Sergeant of the U.S. Marine Corps, Ermey began his film career in several Filipino films before landing parts in such American war films as The Boys in Company C, where he played a drill instructor, and as a helicopter pilot in Apocalypse Now. In Full Metal Jacket, he is displayed in all his glory, giving a career performance and one he’s been playing ever since. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Kubrick said that Ermey came in with his own list of about 150 pages of insults, and of all the character’s dialogue that made it into the film, about half was written by Ermey himself. (C) The role earned him both a Golden Globe nomination and the supporting actor award from the Boston Society of Film Critics.

The comedic tone of Ermey’s half of the movie speaks much to the evolution of Vietnam pictures in American cinema. Remember it was the same year that Barry Levinson released his black comedy Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), starring Robin Williams as a hilarious, improvising radio DJ broadcasting “from the Delta to the DMZ!” It seems that history had finally distanced itself far enough from the actual war that filmmakers were able to start mining bits of dark comedy from it. Williams and Ermey were the champions of the new-found humor.

Still, let’s make no mistake about it. Ermey may give an enormous contribution, spitting lines from a clever script, but the film really belongs to Kubrick. We realize this the minute Ermey is destroyed in an ultra-haunting bathroom scene midway through the picture, which leaves viewers breathless and with no idea what will come next. You’re in Kubrick’s hands now.

Arriving a full seven years after The Shining (1980) and 12 years before Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket was Kubrick’s second to last effort. Here, we see a director at the top of his mad genius game: the long single-take tracking shots of Hartman pacing the barracks; the platoon marching left to right across the frame and then, after Pyle is abused and made to walk with his pants down, the platoon marching right to left; the wide-angle pullback over a line of Vietnamese civilian bodies down in a ditch; the zoom effects during the sniper scene; the pacing of the “shoot me” conclusion for excruciating tension; and the symbolism of images like the “Born to Kill” helmet and the peace sign lapel pin. To Kubrick, this is the duality of war, the hypocrisy of killing as a means to peace. At the root of it all lies the dehumanization of young boys into war drones and killing machines, a process that begins with a simple hair cut and ends when they fire their first round of full metal jackets into another person.

Still, the film has its detractors. The late Roger Ebert found it disjointed, particularly between the first and the second halves, calling the film “a strangely shapeless film from the man whose work usually imposes a ferociously consistent vision on his material.” (D) Ebert also did not like how Kubrick abandoned his trademark sexual symbolism in the film’s second half, after using it so well with phallic rifles in the first half. (D) Others have different gripes, ranging from conventionality to an over-reliance on set pieces. Scholar David Thomson feels Kubrick understands his medium so much to a fault, calling the film “an abomination” because it is so “obsessively disciplined.” (A) In other words, Kubrick revels so much in the idea of cinematic language that he forgets to step back and make sure the entire work fits together.

These are perfectly understandable criticisms. Yet in spite of such detractors, the vast majority of critics (94% Rotten Tomatoes) and casual viewers (8.4 IMDB) hail the film as a war classic. If Kubrick can garner such overwhelming appeal, I feel he should be more than free to flex his cine-language muscles. Perhaps he is working from some sort of different consciousness, best revealed by the admittedly accidental background image during Private Cowboy’s death — a building that eerily resembles the Monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

One challenge to finding where Full Metal Jacket fits into Kubrick’s auteur narrative is his use of a rock ‘n roll soundtrack, feeling more like Martin Scorsese than Stanley Kubrick. No matter, it’s a kickass collection of tunes: Johnnie Wright’s twangy “Hello Vietnam” during the numbing opening montage; Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walkin'” as we enter Vietnam; The Dixie Cups’ “Chapel of Love” as the calm before the Tet Offensive storm; as well as other hits like Sam the Sham & The Pharoahs’ “Wooly Bully,” The Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird” and The Rivingtons’ “Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow.” The lattermost choice was actually chosen by UnderGroundOnline as the third best use of classic rock in cinema history. (B)

Most important are the two songs Kubrick chooses to end his film. After an anguishing execution of a female Vietnamese sniper, the U.S. troops march across a background of flames, climbing high into the night, singing in unison the theme from The Mickey Mouse Club. The juxtaposition of such a song in a warzone is shocking on its own, but it takes on greater meaning if you consider Benjamin Barber’s book Jihad vs. McWorld, represented here by a Disneyfied consumerist culture marching across a foreign country, spreading its influence through violence.

This is the picture Kubrick paints, anyway, so I find it ironic that so many young military recruits hail Full Metal Jacket as a personal favorite. Perhaps the gung-ho “maggots” sequence is a necessary mental preparation, the camaraderie of the men reassuring. But let’s face it: Kubrick paints an anti-war picture that is bleak, driven home by fading to black and drumming the first sounds of The Rolling Stones’ “Paint it Black.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: http://www.ugo.com/filmtv/top11-classicrock/?cur=Full%20Metal%20Jacker#top

CITE C: Tim Cahill. “The Rolling Stone Interview,” Rolling Stone, 1987. Retrieved on 2007-10-11.

CITE D: Roger Ebert, rogerebert.com