Director: Alexander Mackendrick

Producers: James Hill, Harold Hecht, Burt Lancaster

Writers: Ernest Lehman (novella), Ernest Lehman & Clifford Odets (screenplay)

Photography: James Wong Howe

Music: Elmer Bernstein

Cast: Burt Lancaster, Tony Curtis, Susan Harrison, Martin Milner, Jeff Donnell, Sam Levene, Joe Frisco, Barbara Nichols, Emile Meyer, Edith Atwater, The Chico Hamilton Quintet

![]()

“Match me, Sidney.”

When director Alexander Mackendrick came over from Scotland to do his first American picture in 1957, he decided to break from the light, comedic expertise he brought to films like Whiskey Galore! (1949) and The Ladykillers (1955). He instead entered the dark world of film noir, a movement that effectively concluded the following year with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). The project was Sweet Smell of Success, the first film produced by the legendary team of James Hill, Harold Hecht and Burt Lancaster (HHL) and a directorial job that only opened up when writer/director Ernest Lehman fell ill. Mackendrick stepped in gallantly, providing superb, atmospheric control over one of noir‘s final masterpieces, bolstered by each crack of Lehman’s hardboiled script.

Building off such films as The Front Page (1931), His Girl Friday (1940), All About Eve (1950) and Ace in the Hole (1951), Sweet Smell of Success provides a satirical look at celebrity culture and the writers who themselves become celebrities simply by covering. The film explores two equally sleazy figures on opposite ends of the spectrum: (a) the big-shot newspaper columnists who control lives with their typewriters, and (b) the slimy press agents who dig up dirt in the trenches of New York City’s night life, where, as critic Kim Newman put it, “the desperate pay court to the demented and souls are sold for column inches.” (A)

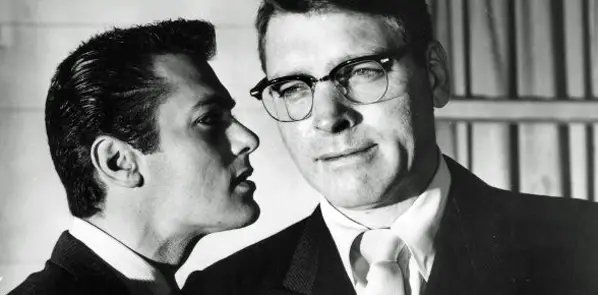

Portraying the former (the newspaper columnist) is Burt Lancaster as J.J. Hunsecker, a menacing figure based off infamous New York gossip columnist Walter Winchell and author of the New York Globe column “The Eyes of Broadway.” Those “eyes” are piercing, accented by thick, black-rimmed lenses that sit above Lancaster’s clenched teeth and hulking shoulders in a role similar to George Sanders’ Addison DeWitt in All About Eve (1950). It was Lancaster’s first antagonist role and one that landed him No. 35 on the AFI’s 50 Greatest Villains, just above Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet (1986). It’s Lancaster’s only spot on the list, the crowning achievement of a powerful career that saw an Oscar nomination for From Here to Eternity (1953), an Oscar win for Elmer Gantry (1960), two more nominations for Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) and Atlantic City (1980), and memorable support as Moonlight Graham in Field of Dreams (1989).

Portraying the latter (the press agent) is Tony Curtis as Sidney Falco, who will do anything to get to the top: bribe, blackmail, brown-nose, even “jump through hoops for J.J.” It was the first truly great performance by Curtis, who had made Lancaster’s character jealous in Criss Cross (1949), starred briefly with Jimmy Stewart in Winchester ’73 (1950) and played Harry Houdini across wife Janet Leigh in Houdini (1953). Sweet Smell of Success launched a powerful streak of performances from 1957-1960, with an Oscar nomination across Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones (1958), his career role as a cross-dresser with Jack Lemmon in Some Like it Hot (1959) and his slave sidekick to Kirk Douglas in Spartacus (1960).

Of all these performances, Sidney Falco may be his most fascinating character, a guy who crudely confesses, “I’m nice to people where it pays me to be nice … and Hunsecker is the golden ladder to the places I wanna get.” As of late, though, Falco has been stuck on the lower rungs, despite his perennial ass kissing. His celebrity “detective” work has practically been shunned from Hunsecker’s columns, thanks to his inability to make good on his latest assignment — to ruin the relationship of Hunsecker’s daughter Suzie (Susan Harrison) and her band-playing boyfriend Steve Dallas (Martin Milner).

It’s no secret around town that Hunsecker has a tight hold on his sister, keeping her in his apartment and keeping her over-sized picture on his desk. The obsession is borderline incestuous and his oppression of her provides insight into his own repressed (and perhaps confused) sexuality. (B) The film functions solely around the emotions of this brother-sister relationship, exploring the motivations of Hunsecker, the effects of his possessiveness when it comes to Suzie and Steve, and just how far Falco is willing to go and who he’s willing to smear to achieve his own personal “glory.”

All this makes for a very deep screenplay in both plot and character. And yet, the main draw to Lehman’s work is his relentlessly sharp dialogue. Voted the WGA’s No. 34 Greatest Screenplay of All Time — just a few slots behind Lehman’s masterpiece North By Northwest (1959) — Sweet Smell of Success puts the “bite” in soundbyte. There’s a new quotable line every few seconds: “If looks could kill, I’d be dead;” “It’s a dirty job, but I pay clean money for it;” “You’re dead, son. Get yourself buried;” “Everyone knows Manny Davis…except Mrs. Manny Davis;” “If you’ve got him for a friend, you don’t need an enemy;” “Maybe I left my sense of humor in my other suit;” “Your mouth is as big as a basket, and twice as empty;” and of course, “I’d hate to take a bite out of you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic.”

The script is so smart and so quick that you may have to watch it multiple times to pick up on all of them. Certain lines requiring having seen the end to understand — “Two rolls got fresh with a baker” — while others carry Biblical connotations — “My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand for 30 years.” It may also take several viewings to fully appreciate the character-driven ending, one that may leave some begging for more, but which becomes all the more perfect the more you think about it. Such may have been the sentiment in 1957, as Sweet Smell of Success emitted only the foul stench of failure among both critics and at the box office. Over the years however, it has increasingly turned up on best lists all over the place, honoring the film as the work of art that it is.

Most of its success relies on a perfection of atmosphere, both in music — a swanky jazz score from Elmer Bernstein and the stylings of the real-life Chico Hamilton Quintet — and in the visuals, thanks to legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe (Hud, Yankee Doodle Dandy), who was nicknamed “Low-Key Howe” for his low-key lighting. Shot on location in Manhattan, the film totally captures the smoky nightclubs that would influence Martin Scorsese on Raging Bull (1980) and the neon signs reflecting off rain-covered streets that would give Scorsese his canvas in Taxi Driver (1976).

Mackendrick works the shadows beautifully, giving both Hunsecker and Falco their moments of diabolically half-lit faces in perfect noir style. Mackendrick is a masterful filmmaker here: providing low-angled shots on Hunsecker in the theater; fading from Hunsecker’s night terrace view to an identical daytime shot; and jumpcutting from Steve’s frightened face to a drumstick smashing a cymbal. Note also his relationship between cinematic space and camera movement, often picking up important elements deep in the field (i.e. Hunsecker sitting in the rear of the Twenty One nightclub) or delaying the camera’s tracking just enough to capture Hunsueker’s jolting presence behind a doorway (a beautifully crafted climax).

While the no-good smear artists get their comeuppance in the end, with a most hopeful final shot, one can’t help but feel the overall despair throughout. A cynical undertone emanates from these sleazeballs driven by that sweet smell of success. It gets in their noses and steers their direction, giving a green light to throw anyone under the bus to get where they want to go. More disheartening is the thought that these people are still out there. It’s the way it’s always been and the way it always will be. As Falco says, “This is life, get used to it.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE B: Tim Dirks, AMC Filmsite