Director: Max Ophuls

Producer: John Houseman

Writers: Stefan Zweig (story), Howard Koch (screenplay)

Photography: Franz Planer

Music: Daniele Amfitheatrof

Cast: Joan Fontaine, Louis Jourdan, Mady Christians, Marcel Journet, Art Smith, Carol Yorke, Howard Freeman, John Good, Leo B. Pessin, Erskine Sanford, Otto Waldis, Sonja Bryden

![]()

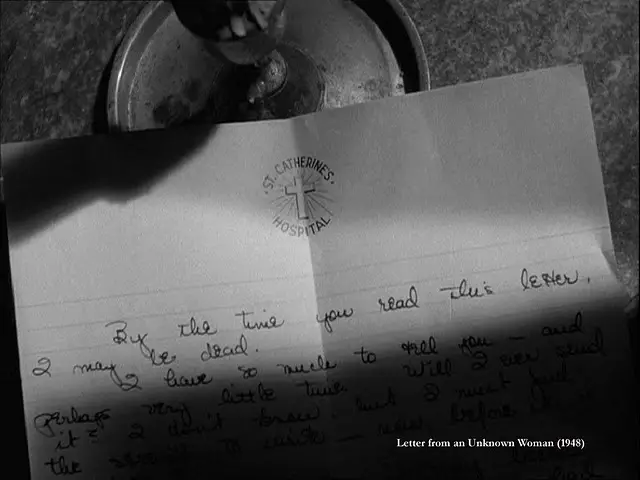

“By the time you read this letter, I may be dead.”

So begins Max Ophuls’ masterpiece Letter from an Unknown Woman, instantly gripping audiences, but not by setting up a mystery thriller as some might guess. The letter’s recipient is not some private eye who must keep reading to find clues to a potential murder. Instead, it’s a suave playboy who must keep reading to see how his own selfish actions have led to the heartache of a woman he does not even remember.

This guy is Stefan Brand (Louis Jourdan), a former concert pianist in 1900 Vienna, who has developed a reputation for romancing more women than he can count. The unknown woman, and writer of the letter, is Lisa Berndle (Joan Fontaine), an ailing woman wanting to get a few important things off her chest. Just as intrigued as viewers, Stefan dives into the letter over some coffee and cognac, and the narrative shifts to Lisa’s story, signaled by a blurry flashback and Fontaine’s narration.

Her letter takes us back to the first day Stefan moved in next door, the day she says, at 14 years old, her conscious life began with a crush on the dashing musician. Creeping to her window late at night, she listens to his piano and pretends he’s playing for her. At one point, she even sneaks into his house. Her actions would seem stalkerish if it weren’t for the presence of Fontaine, whose sweet innocence makes it hard to see her obsession as anything more than romantic.

Still, as the story progresses, viewers discover that this is no ordinary teenage crush. This one will last a lifetime, driving her to abandon her parents and a courtship with a military officer just to be near him, all in spite of the fact that he still has no idea who she is. When he finally does meet her, romancing her with white roses, a night on the town and a passionate night at his place, it amounts to nothing more than a one night stand and an altogether different kind of heartache for Lisa. But no matter how slimy Stefan is, no matter how many women he’s been with, Lisa continues to feel drawn to him, even if she herself becomes married to another man. This is the true tragedy of the film.

Smartly woven by author Stefan Zweig and poetically adapted to the screen by Casablanca co-writer Howard Koch, Letter from an Unknown Woman is a teary, melodramatic look at societal gender roles, the false hopes of love, and how the two tragically intersect. It may be best articulated in Lisa’s sad, written revelation to Stefan: “If you could have only recognized what was always yours, you could have found what was never lost.”

The same could be said to any viewers who, like most critics of the film’s day, find the film overly sentimental. Like Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956) and other Hollywood soaps of the period, Letter from an Unknown Woman has climbed in stature after a closer look.

The reason for this reassessment belongs solely to the legendary vision of German director Max Ophuls. Letter from an Unknown Woman is not only his greatest American contribution, but his greatest contribution, period. Rather than transparently following the characters within their fictional world (like most movies), Ophuls positions his camera in its own time and space, disconnected from the characters and the reality they know. It gazes at them through a restaurant window. It studies them fatalistically through the bars of a gate. It peers at them through a set of curtains on either side of the frame.

Ophuls’ biggest weapon in expressing this vision is using “frames within frames,” windows in time.

This detached approach creates a tone as if the movie knows something that the characters don’t — their fates — an approach that’s proven effective time and again, from Vertigo (1958) to Halloween (1978) to Prisoners (2013). As Lisa says, life follows a “reason beyond our poor [human] understanding,” moving toward a fatalistic end evidenced parallel train promises: “I’ll be back in two weeks.” Critics like Pauline Kael have even gone as far as calling the film “The toniest ‘women’s picture’ ever made.” (A)

In addition to being an objective observer, Ophuls knows how to use subjective camera to his advantage via telling POV shots. The most powerful example comes as young Fontaine swings on a backyard swing, gazing up at a window, as we assume her swinging point of view.

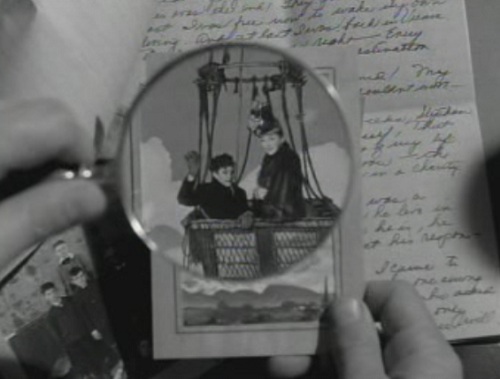

Academics will also point to Ophuls’ masterful use of mise-en-scene, or making symbolic use of every element in the visual frame. Most famously, note how Lisa and Stefan’s entire date is the epitome of phoniness, from talking about wax figures, to taking a ride in a fake train with the background constantly changing. Those who roll their eyes at the datedness of “rear projection” in classic movies should find this scene extra delicious, as Ophuls makes a self-reflexive statement.

The staircase of Stefan’s home carries deeper sexual symbolism with each girl he brings up, begging the question of how many other heartbroken “unknown women” have come before Laura.

Still, my favorite example comes as Lisa’s husband, Johann, threatens to “do everything in his power” to prevent her from returning to Stefan. Ophuls shows dueling handguns and swords hanging on the wall behind Johann, suggesting he intends to duel Stefan as a last resort.

Still, my favorite example comes as Lisa’s husband, Johann, threatens to “do everything in his power” to prevent her from returning to Stefan. Ophuls shows dueling handguns and swords hanging on the wall behind Johann, suggesting he intends to duel Stefan as a last resort.

Untrained eyes won’t grasp all this on first viewing, and rightfully so; it’s not altogether obvious that this duel is about to take place. But after having seen the film once, you’ll realize that Lisa’s letter reveals to Stefan the true identity of the man he is about to go duel in just a few minutes. Viewers who care enough to pay close attention, look for the hints, and piece together the weaving tale will really come to respect the genius of Ophuls’ work. Thus, Lisa’s letter may just as well describe Ophuls’ direction: “I know now that nothing happens by chance. Every moment is measured; every step is counted.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: VHS cover of Legendary Ladies of the Silver Screen collection