Director: Woody Allen

Producer: Charles H. Joffe, Jack Rollins

Writers: Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman (screenplay)

Photography: Gordon Willis

Music: George Gershwin via New York Philharmonic

Cast: Woody Allen, Diane Keaton, Michael Murphy, Mariel Hemingway, Meryl Streep, Anne Byrne Hoffman, Karen Ludwig, Michael O’Donoghue

![]()

Introduction

There’s a moment in Annie Hall where Woody Allen psycho-analyzes himself, penning Annie’s criticism of Alvy: “You’re incapable of enjoying life, you know that? I mean you’re like New York City. You’re just this person. You’re like this island unto yourself.” Two years later, Allen’s obsession with that island would become his most ambitious project, Manhattan, which Allen sculpts as “a metaphor for everything wrong with our culture” and a commentary on trying to live an ethical life while “desensitized by television, drugs, fast food chains, loud music and feelingless, mechanical sex.” (A) He lays out his entire thesis in his opening narration:

“Chapter One. He adored New York City. He idolized it all out of proportion.” Uh, no, make that: “He romanticized it all out of proportion.” Yeah. To him, no matter what the season was, this was still a town that existed in black-and-white and pulsated to the great tunes of George Gershwin.” Uh, no let me start this over. “Chapter One. He was too romantic about Manhattan as he was about everything else. He thrived on the hustle bustle of the crowds and the traffic. To him, New York meant beautiful women and street-smart guys who seemed to know all the angles.” Nah, corny, too corny for a man of my taste. Let me – let me try and make it more profound. “Chapter One. He adored New York City. To him, it was a metaphor for the decay of contemporary culture. The same lack of individual integrity that cause so many people to take the easy way out was rapidly turning the town of his dreams in-” No, it’s gonna be too preachy. I mean, you know, let’s face it, I wanna sell some books here. “Chapter One. He adored New York City, although to him, it was a metaphor for the decay of contemporary culture. How hard it was to exist in a society desensitized by drugs, loud music, television, crime, garbage.” Too angry. I don’t wanna be angry. “Chapter One. He was as tough and romantic as the city he loved. Behind his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat.” I love this. “New York was his town, and it always would be.”

Manhattan was Woody’s answer to the Oscar success from Annie Hall, both starring he and Keaton, both set in his beloved New York City, both captured by legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis, both produced by the team of Jack Rollins and Charles H. Joffe, both featuring the same title credit font, both written by Allen and Marshall Brickman, both featuring the same sidewalk walk-and-talk convos, the same cultural references and the same place in film history by teaching late 20th century audiences the joys, pains and nuances of dating in the modern age.

There’s never been a better love note to the city, as Allen chooses to shoot in black and white to accent Allen’s own romanticized image of it (“He idolized it all out of proportion”). Perhaps this suggests a certain vain desire by Allen for artistic expression in his choice of B&W film stock lined with George Gershwin selections. But the result is a movie only Woody Allen could have done, existing more as a witty romance than a laugh-out-loud venture like Annie Hall, a romantic dramedy more than a romantic comedy.

![]()

Plot Summary

While the film may arouse fewer laughs than Annie Hall, its characters are more likable, replacing the negatively-viewed Alvy Singer with a more favorable Isaac Davis (Allen), a 42-year-old TV comedy writer, reeling from his ex-wife’s (Meryl Streep) decision to write a tell-all book about why she left him for her lesbian lover. This makes Isaac a familiar neurotic intellect like other Allen characters, but one who adheres to a more stringent moral code: “I don’t believe in extra-marital relationships. I think people should mate for life, like pigeons or Catholics.”

Thus, he is critical of his friend, Yale (Michael Murphy), who while married to a sweetheart named Emily (Anne Byrne Hoffman) is having an outside affair with a journalist from Philly named Mary (Diane Keaton). Soon, however, Isaac’s own morality is tested, as he develops a growing crush on an innocent teenager named Tracy (Mariel Hemingway). When Tracy announces she’s going to study abroad in Europe, Isaac begins dating Mary (Allen & Keaton reunited), but only after he asks Yale’s permission (that’s the kind of guy Isaac is). Unfortunately for Isaac, Yale doesn’t give him the same courtesy when he rekindles his affair with Mary, leaving Isaac confused as to whether he should return to the teenage Tracy, who’s about to leave the country.

![]()

Woody the Writer

The script, voted No. 54 all-time by the Writers Guilds of America, should sound familiar to the genre and location. Hell, the writing staff of Friends could have subconsciously shaped the character of Ross directly from Allen’s Isaac, having him divorced by a lesbian wife, dating a high school girl in one episode, and having him make romantic use of a planetarium in another. But this sort of influential creativity is only part of the film’s power. The rest lies in the complexity of its character study, demonstrating an equal attempt at capturing truth as it does affecting audience response.

The Isaac-Tracy relationship appears creepy in hindsight, knowing Allen’s eventual real-life perversions. In 1992, it was revealed that a 56-year-old Allen was dating 21-year-old Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of his longtime girlfriend Mia Farrow, who had adopted Soon-Yi at age 8 with then husband Andre Previn in 1978. The couple divorced in 1979 and Farrow began dating Allen in 1980. Allen insisted there was no scandal, seeing as it wasn’t his adopted daughter initially — it was inherited from Farrow’s previous marriage. Still, many of us found the entire thing creepy.

And yet, just like Hitchcock’s male gaze or Polanski’s rape tendencies, the off-screen perversions of filmmakers make for fascinating on-screen character studies. In Manhattan, Allen handles the Isaac-Tracy relationship tenderly, portraying Isaac’s guilt of leading on a teenager, and earning Mariel Hemingway an Oscar nomination for her believable innocence as Tracy.

Mary’s character is equally developed, a confused imbalance of mind and body. It’s no coincidence that she uses pretentious highbrow words like “textural” and “integrated” in the same sentence with “bullshit.” Ultimately, she admits that she is “too cerebral,” a fitting self-realization considering she’s having an affair with a professor named “Yale.”

![]()

Woody the Director

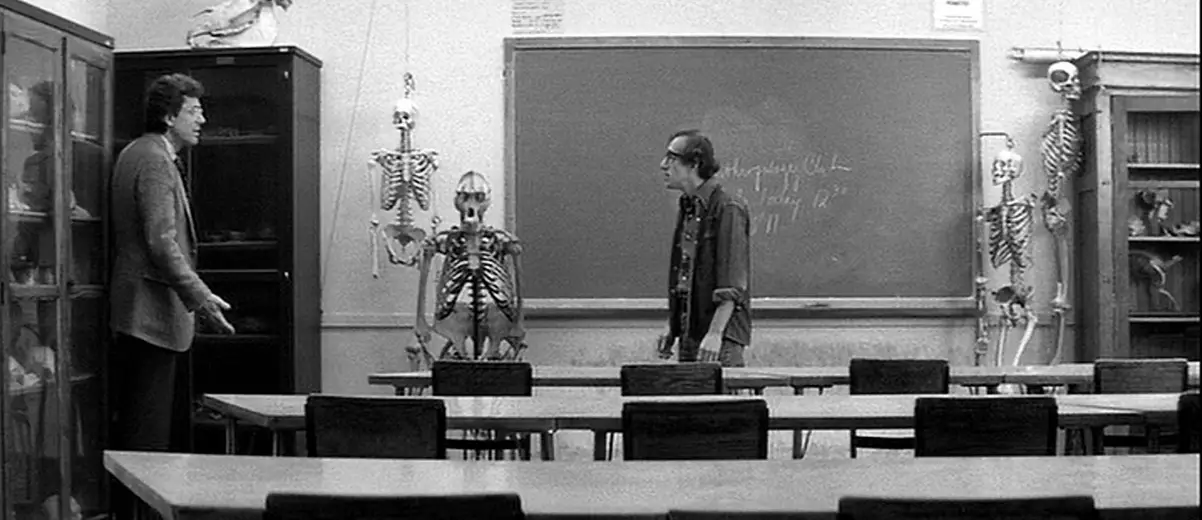

This mind-body imbalance is the key subject in Manhattan, particularly in the character of Yale, who too often surrenders to the pleasures of his body (having affairs with women) and then uses his mind to rationalize it. This very idea leads to Allen’s most poignant directorial touch in a scene where Issac confronts Yale in an empty classroom. “You’re not honest with yourself,” Isaac says, “You rationalize everything.”

While this is certainly powerful writing, Allen the director supports this theme visually with brilliant us of mise-en-scene (the symbolic placement of all elements within the frame). Look how he places his two male characters in shots with anatomical skelletons, showing a full skeleton next to Isaac (symbolizing his balance between mind and body), while showing only skulls behind Yale (symbolizing his disconnect between mind and body through his attempt to rationalize immorality, his being “too cerebral” like Mary).

It may be Allen’s greatest example of having now mastered his craft as a filmmaker, to express his social commentary through dialogue and metaphorical visuals. Allen himself explained it like this: “We have this opulent, relatively well-educated culture, and yet…we see people lose themselves…because they don’t deal with their sense of spiritual emptiness.” (A)

In other words, Manhattan is a look at how hard it is for a moral guy like Isaac to survive in a world of Yales and Marys. And this world isn’t going away. At least, that’s what Allen suggests in his continued use of the empty-shot techniques he first discovered in Annie Hall. Throughout Manhattan, we get wide-angle shots of various city streets, while the characters (i.e. Yale in a phone booth) occupy only a small fraction of the screen.

The chief example of this comes in a waterfront scene where Isaac, Mary, Yale and Emily stroll along a pier. The scene begins with an empty shot of a pier, after which the four characters enter the frame, reading embarrassment excerpts from Emily’s tell-all book. As Isaac slinks back in shame, the other three exit the frame, leaving only Isaac alone in a state of metaphorical loneliness. Seconds later, he exits the frame himself, ending the scene with another shot of the empty pier.

The recurring technique is a metaphysical statement by Allen that the world exists prior to us, that we come in with our problems and then leave, but the world remains the same. This sheds a bit of light on Allen’s own neurosis. At the outset of Annie Hall, a young Alvy frets about the universe expanding, rendering mortal life irrelevant. Allen continues this idea in Manhattan as Isaac says, “We become neurotic about the little things in our lives only because we can’t deal with the big questions of the world.” In other words, our life problems are but small potatoes in the grand scheme of things. This overall earthly structure around us that long outlasts our petty problems. Such may be his fixation on New York City as perhaps the grandest man-made imprint on this constant universe.

His love affair with the city makes for some flat-out beautiful compositions — the opening montage of city images; Isaac and Mary running through the rain and sharing a newspaper for an umbrella; the two of them sharing romantic moments as mere silhouettes inside the darkness of a planetarium; Isaac and Tracy taking a carriage ride through Central Park; and the poster shot of them sitting beneath the 52nd Street Bridge.

Still, the most mesmerizing shot comes with black-and-white fireworks exploding against the night skyline, all set to Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” The all-Gershwin soundtrack recalls An American in Paris (1951), or in this case, “A New Yorker in New York,” even down to the music being interpreted by the New York Philharmonic.

![]()

Final Thoughts

It’s all a grand undertaking, one that might give the impression of extremely high brow. But even Allen admits he hates that “pseudo-intellectual crap,” giving his own film a perfect balance between mind and body. Unlike Keaton’s character, Allen’s direction is never pretentious. He is that smart a writer, that clever a jokester, that proud a New Yorker, that natural an artist. Whether you’ll like it is a matter of personal preference.

Either you love Woody Allen, or you’re annoyed by him. Either you get most of the references, or they fly right over your head (“When it comes to relationships with women, I ought to get the August Strindberg award”). But every viewer has to at the very least recognize Manhattan as a stylized masterpiece with much more going on underneath the surface, echoing Annie’s comment to Alvy in Annie Hall: “You were great … I think I’m starting to get more of your references, too.” Even if you shrug off his films as “too intellectual,” Allen has an answer for you, as Isaac says: “You’re going by audience reaction? This is an audience raised on television, their standards have been systematically lowered over the years.” It’s Allen’s own genius way of reminding future generations to beware of the clear dumbing down of society.

Then again, as Tracy tells Isaac, “Not everybody gets corrupted. You have to have faith in people.” Maybe there is hope that future generations will continue to appreciate the genius of Woody Allen, who said of his New York City love letter: “I like to think that, 100 years from now, if people see the picture, they will learn something about what life in the city was like in the 1970s.” (A) As for me, I have to add Woody Allen among the “list of things that make life worth living,” which Isaac compiles: “Groucho Marx, Willie Mays, the second movement of the Jupiter Symphony, Louie Armstrong’s recording of “Potato Head Blues,” Swedish movies, Sentimental Education by Flaubert, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra, those incredible apples and pears by Cézanne, the crabs at Sam Wo’s and Tracy’s face.”

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Manhattan DVD booklet