Director: Arthur Penn

Producer: Warren Beatty (Warner Bros.)

Writers: David Newman and Robert Benton (screenplay)

Photography: Burnett Guffey

Music: Flatt & Scruggs, Charles Strouse

Cast: Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, Gene Hackman, Estelle Parsons, Michael J. Pollard, Gene Wilder

![]()

Introduction

1967 was the year that American cinema grew up. Hollywood’s Golden Age of the ’30s and ’40s had long since given way to the sword-and-sandal epics of the ’50s and ’60s. Meanwhile overseas, the French New Wave had shattered every convention known to man. When a crop of young American filmmakers saw these edgy French flicks, they were inspired to create their own period of maverick filmmaking known as the “Hollywood Renaissance,” marking the arrival daring new voices like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, John Cassavettes, Sam Peckinpah, George Roy Hill, Hal Ashby, John Boorman, John Schlesinger, William Friedkin, Roman Polanski, Peter Bogdanovich, Mike Nichols, Woody Allen, Brian DePalma, Terrence Malick, Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola.

Helping the cause was 1967’s removal of the Hays Code in favor of the MPAA rating system. That meant filmmakers could make sexier, more violent films, as long as they carried a particular rating. Out of this grew anti-establishment pieces that broke down barriers of race, religion and sexuality. And while the title of Peter Biskin’s controversial book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls sets the bookends at 1969-1980, the Hollywood Renaissance truly ran from 1967-1980.

October 1967 brought In the Heat of the Night (1967), November brought Cool Hand Luke (1967), and December brought both The Graduate (1967) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). But predating all of those films was a revolutionary picture that shocked audiences in August ’67, a film with unprecedented violence and simmering sexuality, film’s greatest indication that the times they were a changin’, the one and only Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Arthur Penn’s crime drama stylistically redefined cinema in the way Pulp Fiction (1994) would decades later. Bonnie and Clyde gave American cinema the jolt in the arm that it needed, becoming one of the most important “biography” films ever done, while reminding us how much myth-making goes into the process. The film at times portrays the outlaw duo against their notorious image, making them novice, clumsy robbers, and suggesting that pop culture has given them an identity that is far from the reality. As John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) so eloquently says, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” When it comes to Bonnie and Clyde, it’s now nearly impossible to separate the truth from the movie from the myth.

![]()

Plot Summary

During the infamous Dust Bowl and Great Depression of the 1930s, the same time that Tom Joad was fighting to survive in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), we find Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) bored and lonely, beating against her brass bedpost in Texas.

That’s when the limping Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) shows up outside her window. With one “hey, boy” call from Bonnie out the window, a legendary love affair is born.

We watch as the duo forms the infamous Barrow Gang, a pack that includes Clyde’s yokel brother Buck (Gene Hackman in his breakthrough role), Buck’s whiny wife Blanche (the Oscar-winning Estelle Parsons) and the grungy mechanic C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard). Together, the fugitive group tears across the fields of the midwest, robbing banks and outrunning the cops to across state lines.

![]()

Bullet-Riddled Screenplay

Co-written by David Newman (What’s Up, Doc?) and Robert Benton (Kramer vs. Kramer), with uncredited contributions by Beatty (Reds) and Robert Towne (Chinatown), the screenplay pulls many elements from the B-cult classic Gun Crazy (1949), which was also based on the story of Bonnie and Clyde. Even so, the script for Bonnie and Clyde stands on its own merits, part comedy, part melodrama, while contributing one of the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes: “We rob banks!”

You’ll note that Clyde first says the line with ambitious pride to a guy whose home has just been foreclosed. Today’s viewers can relate to this sentiment, with conservatives furious about bank bailouts, liberals staging Occupy Wall Street protests and both sides frustrated by the collapse of the housing market. Struggling Americans of the ’30s followed Bonnie and Clyde so rabidly in the newspaper because they were, in their eyes, noble populists fighting back against the greedy establishment that had sunk the nation into the Great Depression.

By the time we hear Bonnie repeat the line, “We rob banks,” the duo has become well known across the nation as notorious outlaws. The pride in her voice says, “Yeah, that’s us you’ve been reading about.” On both occasions, we’re invited to like these immoral characters in the same way we like the immoral men of The Godfather (1972). In their world, they’re the good guys. When Clyde first robs a bank to impress Bonnie, we the audience remain outside in the street, hiding the actual brutality of the hold-up and showing only the cash payoff. This favor-building image causes Bonnie — and we the viewers — to go along for the ride.

The script also cleverly weaves in the notion of celebrity, as Bonnie and Clyde photograph themselves holding tommy guns and posing with tied-up cops.

When they need to hide out, they do so in a movie theater, watching the escapist Depression film Golddiggers of 1933 (1933), which leaves Bonnie singing, “We’re in the Money.” And, in the ultimate example, Bonnie submits a manifesto poem to the newspaper. When Clyde says to her, “I bet you’re a movie star,” he’s describing his vision for her, and possibly her own suppressed vision of herself.

![]()

Movie Stars

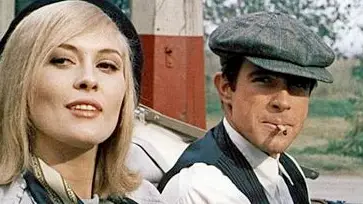

Speaking of “movie stars,” you won’t find two more beautiful people than Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty in all their youthful glory in 1967. “That movie taught me what a star looks like,” Halle Barry told the American Film Institute. (A)

What many folks don’t know is that Beatty started off solely as the film’s producer. Bonnie and Clyde was his debut project and it was he who bought, the script, ordered the rewrites, pushed for the film to have social meaning and made casting decisions. (B) His sister, the great Shirley MacLaine (The Apartment), was an early favorite to play Bonnie. But when Beatty decided to play Clyde himself, he decided not to use his sister for obvious sexual reasons. Instead, Beatty considered Jane Fonda, Tuesday Weld, Ann Margret, Leslie Caron, Carol Lynley, Sue Lyon, Cher and Natalie Wood, whom Beatty begged to play the role. Wood declined to concentrate on her therapy.

And then, just like Vivien Leigh surprising everyone as a late arrival Scarlett O’Hara, Faye Dunaway snatched the role. For my money, Dunaway as Bonnie Parker is one of the sexiest women ever to grace the screen. You ladies will probably say the same about Beatty. Together, they sizzle, earning a #65 spot on the AFI’s 100 Passions and inspiring the movie poster tagline: “They’re young. They’re in love. And they kill people.” Voted the AFI’s #42 Greatest Villains, the duo is extremely likeable, paving the way for all anti-heroes to follow, from Tony Montana in Scarface to Walter White in Breaking Bad.

Beatty also had a good eye for his supporting cast, earning an Oscar nomination for Michael J. Pollard for Best Supporting Actor and winning an Oscar for Estelle Parsons as Best Supporting Actress (though I personally find her performance annoying as hell). As if that wasn’t enough, Bonnie and Clyde also marked the film debut of Gene Wilder as a comical kidnapped undertaker, leading to his casting by Mel Brooks the following year in The Producers (1968), which paved the way for legendary roles in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), Blazing Saddles (1974) and Young Frankenstein (1974).

Still, Beatty’s biggest casting coup was the discovery of a little known actor named Gene Hackman, who was so good in Bonnie & Clyde that he was playing Popeye Doyle in The French Connection (1971) just four years later.

![]()

Arthur Penn: Visionary

Just as Dunaway wasn’t Beatty’s first choice to play Bonnie, Arthur Penn was not his first choice to direct. The film was originally offered to François Truffaut (The 400 Blows), the best-known director of the French New Wave. While Truffaut made early contributions to the script, he eventually passed on the project to make Fahrenheit 451 (1966). Beatty next approached the second most famous French New Wave director, Jean-Luc Godard, who had told a tale similar to Bonnie and Clyde in Breathless (1959), about two lovers on the run. The film’s investors eventually forced him off the project because he reportedly wanted to change Bonnie and Clyde to teenagers and relocate the story to Japan. Later, after attending a screening of the completed film, Godard was asked what he thought of the film and reportedly replied, “Great! Now let’s go make Bonnie and Clyde.”

While the thought of a Godard remix in a Japanese setting is bizarrely fascinating, this was a tale about the American Depression, a tale of American gangsters with a truly American following in newspapers on American tables. And so, the eventual choice of Arthur Penn bleeds with authenticity. Born in Philadelphia, Penn made his way to New York City, where he won the Tony for Best Director for the Helen Keller story The Miracle Worker in 1960. Two years later, he earned an Oscar nomination by bringing the play to the big screen in The Miracle Worker (1962), proving he could handle an American biopic on film. He would go on to make other daring films like Alice’s Restaurant (1969) and Little Big Man (1970), but none was as influential — or successful — as Bonnie and Clyde.

Penn gets to work on his fatalistic imagery right from the start. Note Bonnie’s “doomed descent” down the stairs to meet Clyde in the opening scene. A similar shot was used by David Lynch as Kyle McLachlan embarks on his night journey in Blue Velvet (1986).

Note the way Penn elicits sexual tension through visual subtext. To Penn, objects aren’t simple props; they are tools to mine his character’s simmering desires. He makes women everywhere wish they were a matchstick and guys everywhere wish they were a bottle of pop.

The bite of an apple is not merely a snack for the road, it’s a symbol of Adam & Eve temptation.

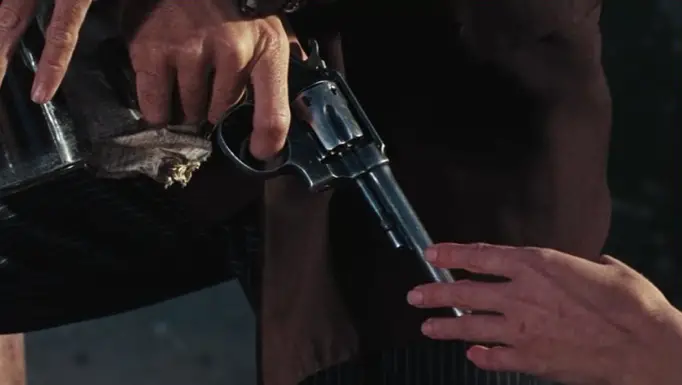

Clyde’s gun is not merely a weapon, it’s a phallic symbol, erotically stroked by Bonnie from the outset.

The phallic gun is used to shoot several “O”-shaped images, as in “orgasm,” whether it’s the “O” shape of a tire swing or a series of zeroes stenciled on a store window.

But Penn doesn’t stop there. He further uses the phallic symbolism of the gun to express Clyde’s own impotence. Note how the gun points downward as it lays on the bed after a failed lovemaking attempt. Time and again, Bonnie tries to approach him sexually, and time and again Clyde can’t get it up.

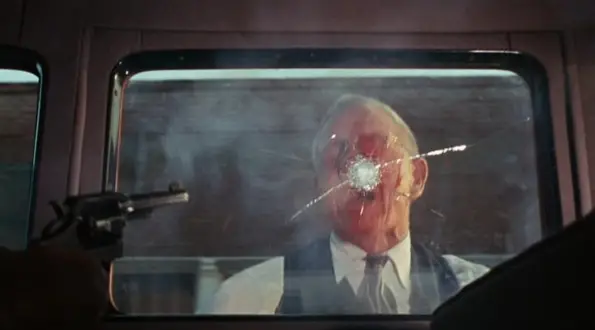

Penn also understands the importance of “frames within frames” to signify his protagonists’ quest for celebrity, to quite literally be captured in frames of time. In addition to the black-and-white photos flashed in the opening credit sequence, Penn constantly uses the image of window frames as metaphors for the characters’ own photographic sense of fame. The most telling example comes when Clyde kills his first man, shooting a banker through a car window. The moment serves as a powerful discovery to Clyde that his “framed” self-image of fame has dangerously encroached on reality. This image, a bullet-holed car window, tragically reappears in the film’s final image (more on this later).

Midway through the film, Penn offers one scene that sticks out like a sore thumb — and for good reason. It happens when Bonnie visits her mother. Here, Penn shifts to an over-exposed film stock to capture Bonnie’s dream-like fantasy that she can simultaneously maintain a family life and a life of crime. The facial reactions of Bonnie’s mother show she knows it’s an illusion, and the washed out look shows what crime can do to a family.

Still, no matter how much genius precedes it, there’s no topping the film’s rapturous conclusion. It’s one of the finest cases of a climax that we historically know is going to happen (i.e. the Titanic hitting the iceberg), but Penn shoots it in a rway that makes it absolutely horrific. The sequence draws glaring attention to Dede Allen’s brilliant editing, Burnet Guffey’s Oscar-winning cinematography and Danny Lee’s bullet-wound special effects. Bonnie and Clyde made pioneering use of “squibs,” little devices that shoot bursts of blood, accurately capturing the 1,000 rounds of ammunition that police pumped into the bodies of the real-life Bonnie and Clyde.

“I thought that if were going to show this [violence], we should show it. We should show what it looks like when somebody gets shot. TV coverage of Vietnam was every bit, perhaps even more, bloody than what we were showing on film.” (C)

To see such beautiful bodies peppered with bullets in slow-motion remains a shock to this day, let alone in 1967. Penn’s bloody ballet paved the way for Sam Peckinpah’s use of slow-motion violence in The Wild Bunch (1969), while the bullet-riddled action clearly inspired the way Francis Ford Coppola shot Sonny’s demise in The Godfather (1972) and the way Antoine Fuqua shot Alonzo’s demise in Training Day (2001). Unlike those films, Penn ends his film with an abrupt cut to black immediately following the violence. His characters are dead. His story is over. There’s no need for a tidy resolution.

![]()

Reaction & Legacy

The mesmerizing finale continues to wow critics decades later. Film scholar David Thomson called the slow-motion killing “orgasmic,” while Rolling Stone critic Peter Travers said, “The violence, especially the slo-mo climax, retains its power to floor you,” ranking the film No. 39 in his 100 Maverick Movies.

But not everyone was so complimentary upon the film’s release. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times was so turned off by the film’s brutality that he used it as his rallying cry against the increasing violence in American films. Thankfully, legendary critic Pauline Kael pushed back in a famous freelance piece that earned her the staff critic position at The New Yorker, while Crowther was fired by The Times for being out of touch with the public. After all, Bonnie and Clyde was the fourth highest grossing movie of 1967.

My how the movies have changed! Penn’s style is likely “out of touch” with today’s mainstream public, but that’s no fault of Penn’s. Penn made movies in an era when art masterpieces were also the top grossers. In the sixties alone, nine of the decade’s Best Pictures were Top 10 yearly grossers. Today, just three Top 10 grossers have won Best Picture since 2000!

One might trace this shift to a quote Penn said in 1982, the same year Spielberg made E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982). Penn lamented the changing direction of Hollywood: “The movies have changed. There’s now this wonderful storyteller Spielberg making benign movies that are enormously successful, while I’m known mainly for making movies about people shooting and cutting each other up. I love his work, but I could never make stuff like that.” (C) Indeed, the early ’80s marked the end of the Hollywood Renaissance, as the Spielbergs and Lucases who rose to fame in that era with American Graffiti (1973) and Jaws (1975) took a hard right toward popcorn blockbusters. Lucas and Spielberg knew the secrets of the masters, but many of their followers do not.

My hope is that the sheer pop culture influence of Bonnie and Clyde will draw more and more mainstream converts to Penn’s brand of filmmaking: symbolic, artful and filled with subtext. New generations have heard of the gangster duo everywhere from rap — 2Pac (“Me and My Girlfriend”), Eminem (“’97 Bonnie and Clyde”) and Jay-Z (“’03 Bonnie and Clyde) — to country — Merle Haggard (“Legend of Bonnie and Clyde”) and Travis Tritt (“Modern Day Bonnie and Clyde”). What a fitting legacy for a film that itself turned the five-string bango piece “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” into a Billboard Top 100 song and earned Flatt and Scruggs a ’68 Grammy for Best Country & Western Duet.

Today, it’s hard to tell which pop culture references are an ode to the film Bonnie and Clyde and which are an ode to the historical figures themselves. The two are undoubtedly intertwined. And the images of Beatty and Dunaway are there in our minds with each passing remake, including the miniseries Bonnie & Clyde (2014) on A&E, Lifetime and the History Channel.

The continued interest in these outlaws speaks volumes to eternal fascination in the necessity of outlaws, because sometimes in society, the outlaws are the ones that push the limits of possibility and keep the higher powers in check. What would the media world look like today without digital outlaws like Sean Parker at Napster? What would American foreign policy be without the revelations of Julian Assange at Wikileaks? And what would American domestic policy be without N-S-A leaker Edward Snowden? In the land of the outlaws, the line between hero and villain is eternally blurred, and no outlaws are more notorious than Bonnie and Clyde. It’s only fitting that the film responsible for telling their story was equally rebellious.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: AFI 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary), CBS broadcast

CITE B: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE C: IMDB Trivia