Director: David Lynch

Writer: David Lynch (screenplay)

Producer: Fred C. Caruso (De Laurentiis Entertainment Group)

Photography: Frederick Elmes

Music: Angelo Badalamenti, David Lynch

Cast: Dennis Hopper, Isabella Rossellini, Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, Hope Lange, Dean Stockwell, George Dickerson, Priscilla Pointer, Frances Bay, Jack Harvey, Ken Stovitz, Brad Dourif, Jack Nance, J. Michael Hunter

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Screenplay

- Frank & Dorothy: Hopper & Rossellini

- Jeff & Sandy: Kyle & Laura

- Real vs. Unreal: Suburbia’s Dark Underbelly

- Innocence Lost: The Noir Night Journey

- Voyeurism & Complicity

- A Surrealist Painter’s Touch

- Parallelism & Familiar Image

- Enveloping Music

- Pop Culture

- Final Thoughts

Introduction

Ask mainstreamers their favorite movies of the ’80s, and you’ll likely hear some combination of The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Back to the Future (1985), The Breakfast Club (1985) and When Harry Met Sally (1989). But if you ask most critics, it’s the erotic thriller Blue Velvet, written and directed by the wonderfully weird David Lynch, who shows his ’86 colleague Top Gun the true definition of a “danger zone.”

In the 2002 Sight & Sound critics poll, David Thomson voted Blue Velvet not just his favorite movie of the ’80s, but his favorite film of all time. Thomson sang the highest of praises, saying, “It would be as hard to advance on Blue Velvet as it must have been to work after Citizen Kane.” (A) That sentiment was echoed by Peter Travers, who called Blue Velvet a “perverse masterwork” and ranked it #9 in Rolling Stone‘s 100 Maverick Movies.

Why, then, is there a backlash from mainstream viewers, who gave higher box office receipts to 76 other movies that year? Why does the public rate it a 7.8 on IMDB? Why did Roger Ebert give it just one star in 1986? And why does it still only get two stars on my Comcast cable box, compared to the 92% rating on rottentomatoes?

The answer: Blue Velvet is not only odd, but it goes for something that transcends cinema. As a first-time viewer, you share in the main character’s uncomfortable departure from your safe movie-going existence. You go along with it, because you’re intrigued, but by the time the velvet curtain drops, you aren’t sure what to make of it. Wasn’t half the movie campy, corny, even poorly written? And how does that compute with the other half, which is the exact opposite — a brutally real underworld? Finally, you contemplate it long enough and you realize the corniness and brutality are both there for a reason: two contrasting views on the world around us, presented in two contrasting styles by a director daring enough to challenge us and to comment on the film medium itself. Siskel and Ebert famously clashed over this very notion. My goal, in this case, is to convert you from Eberts to Siskels:

Plot Summary

Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) works in his father’s hardware store in a sleepy little lumber town, aptly named Lumberton. Here, all appears normal, until one day Jeffrey stumbles across a human ear in a field and takes it to his neighbor, Detective John Williams (George Dickerson).

Unsatisfied with letting the police handle it, Jeffrey decides to conduct his own private investigation. He enlists the detective’s daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), to dig up information about the case, and the two plot their amateur detective work from the booths of a diner.

The investigation quickly leads them to battered nightclub singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), who performs bizarre renditions of Bobby Vinton while bathed in blue light. Craving more, the two decide to break into Dorothy’s apartment, but once inside, Jeffrey learns just how deep he’s in.

He’s stumbled across a complex kidnapping scheme, in which a drug-addicted lunatic, Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), blackmails Dorothy into sex by holding her son and husband hostage. As Jeffrey gets closer to solving the mystery, he grows physically closer to Dorothy and psychologically closer to Frank in a way that terrifies him.

Screenplay

Lynch’s script is a masterwork with so many nuances you don’t notice the first time around — like Frank saying the phrase, “Now it’s dark,” each time the film takes a darker turn. We’ll explore these more as we progress through this review, but before we dive into those depths — before we dive under the grass of Jeffrey’s front lawn — we should first examine the well-cut grass on the surface — the unraveling mystery plot.

Is there a better catalyst than finding a severed ear? We’re instantly hooked. At each step, Lynch sucks us in more. We know only darkness awaits, but we press on anyway in an almost obsessed curiosity. Why do it, Sandy asks? To paraphrase Jeffrey, it’s because, “We are seeing something that was always hidden. We’re involved in a mystery.” And not just any mystery; one that’s #8 on the AFI’s Top Mysteries of All Time.

The mystery plot is what makes Blue Velvet Lynch’s most accessible film, save for maybe Elephant Man (1982). It’s far less ambiguous than Eraserhead (1977), which Lynch brags no critic has ever interpreted correctly, and Mulholland Dr. (2001), where he provides “clues” on the DVD booklet but refuses to reveal the answers. For all its weirdness, Blue Velvet at least feigns a clear conclusion. The villain is destroyed, the conflict is resolved, and the two young sleuths come out more mature. Still, as Dorothy takes her son back into her arms, and we hear the lyrics, “I still can see blue velvet through my tears,” we wonder whether these characters are scarred forever. Like all good scripts, we’re left satisfied, but also left to wonder.

The bittersweet finale is befitting of a script that mines Hitchcockian suspense and dark comedy from the same set pieces. One second we’re terrified as Frank chases Jeffrey into Dorothy’s apartment; the next we’re laughing at a hilarious police radio bit. As Lynch says, “Ideas that string themselves together, they don’t always neatly form a one-genre film. The idea of handcuffing yourself to a genre is, I think, pretty absurd.”

Frank and Dorothy: Hopper and Rossellini

Still, the greatest part of Lynch’s script is the depth of its characters. Frank Booth is as complex a character as you’ll see, stuck somewhere between supplicant child and dominant male, referring to himself as “Daddy,” then calling Dorothy “Mommy,” and saying, “Baby wants to f*ck.” He is unable to communicate on a normal level, which prevents him from properly expressing his deep affection for Dorothy. His constant spouts of profanity are his only way of expressing himself, so that one minute he’s engrossed in a song, and the next, he’s shutting it off and shouting, “Let’s hit the f*cking road!”

For a performance so memorable, it’s crazy to think Hopper doesn’t enter the picture until 42 minutes in. Once he’s in, you’ll never forget it — a monster cursing uncontrollably, downing bourbon and inhaling nitrous-oxide through an oxygen mask. It’s a credit to Hopper’s charm that he could take a character this vile and turn him into a charismatic figure quoted by everyone from Freddy Kreuger to Pauly Shore (see “Pop Culture” below). It was the performance of his career, voted #36 on the AFI’s 50 Greatest Villains.

Hopper said he understood Frank, that in a way he was Frank, as a former addict who directed the drug-laced Easy Rider (1969). Hopper brought these hallucinatory experiences to the screen, like the notion of studying his own hand, just to make sure it’s there. Frank Booth was Hopper’s first role since getting out of rehab, and thus resurrected his career, along with his Oscar-nominated alcoholic dad in Hoosiers (1986) the same year. As much as I love Hoosiers, the Academy had once again made the safe pick over the deserving pick.

Later, Hopper would tell Bob Costas that his drug use was unnecessarily dangerous, pointing to other actors who have reached dark places through simple research.

To that point, some of his best moments come when he’s not a raging lunatic. There are occasional moments of tenderness, like getting caught up in the music during Dean Stockwell’s rendition of “In Dreams,” or clutching a piece of Dorothy’s blue velvet robe at the nightclub as she sings. Both examples show Hopper’s desire to make Frank a human first, monster second.

The above scene also showcases the phenomenal contribution of Isabella Rossellini, daughter of actress Ingrid Bergman (Casablanca) and Italian filmmaker Roberto Rossellini (Rome, Open City). Rossellini endured a grueling shoot, asked to expose herself to Hopper and walk down the street entirely naked. The performance earned her an Independent Spirit Award, but for years she blamed herself for the film’s mixed reviews and second guessed Lynch’s decision to use her instead of Helen Mirren. (F) Hopefully now, we can all look back on the film and appreciate how much she put herself out there.

Her character is every bit as complex as Frank. She’s a woman caught dangerously between repulsion and attraction, hit so many times she now considers it affectionate, and one who adopts Frank’s tactics — “Don’t look at me!” — in order to feel the power of her abuser. Her public affair with Lynch only adds to the dynamic, especially considering that Lynch was also romantically involved with Dern.

Her character is every bit as complex as Frank. She’s a woman caught dangerously between repulsion and attraction, hit so many times she now considers it affectionate, and one who adopts Frank’s tactics — “Don’t look at me!” — in order to feel the power of her abuser. Her public affair with Lynch only adds to the dynamic, especially considering that Lynch was also romantically involved with Dern.

Jeff and Sandy: Kyle and Laura

Also the daughter of famous parents (Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd), Laura Dern is the perfect counterpoint to Rossellini. She may be most famous for Jurassic Park (1993), but she first gained stardom as the beautiful flower of David Lynch, a relationship that continued into Wild at Heart (1990), for which Lynch won the Palm d’Or at Cannes and where Dern played a much flashier role. In Blue Velvet, she’s reminiscent of the virginal Juliette Lewis in Cape Fear (1990), epitomizing quiet innocence and named after the malt shop memory of Sandra Dee.

Taking all this into account, the casting of MacLachlan as Jeffrey becomes all the more interesting. Not only does MacLachlan look like Lynch, he’s now cast as Lynch’s on-screen proxy, caught between Lynch’s two women. Lynch must have seen a reflection of his own suburban youth in MacLachlan, who he cast in the commercial flop Dune (1984). Blue Velvet was just his second performance, but his synergy with Lynch led to his casting as the lead in Lynch’s cult TV series Twin Peaks (1990). Today, you know him as Trey from Sex and the City (1998) and Orson from Desperate Housewives (2004).

You might call the film “Green Velvet” due to the inexperience of most of the cast, with MacLachlan in just his second career role, Dern in one of her earliest roles and Rossellini in her self-proclaimed “second” major role. You could argue this makes them look amateurish next to the veteran Hopper, but in a weird way, in this film, it actually works. It plays into the phoniness Lynch wants from his Lumbertonians in a world that needs to be over-the-top — MacLachlan’s “chicken walk” — in order to set up a false utopia that he can both expose and demolish.

Real vs. Unreal: Suburbia’s Dark Underbelly

Alright, now we’re starting to dive beneath the grass. If the mystery plot and acting are the surface level hooks, the fertilizer that allows it to grow are the ideas that sparked the creation. Lynch says it was sparked by three ideas — red lips, green lawns and Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet.” The creative process in bringing these ideas into fruition is a wonder of Lynch’s imagination.

Setting the precedent for American Beauty (1999), Lynch presents a suburban neighborhood that’s richer than anything in the real world, but one that features all the elements Americans fancy their neighborhoods to be. Colorful flowers. White picket fences. All-American bungalow-style homes. Everything is impossibly perfect, down to a fireman waving directly at the camera.

But that’s just it. Lynch wants a utopic setting on the surface to contrast with the incredibly dark secrets that lie underneath. The criminals Andy Griffith locks up in Mayberry must come from somewhere. So as Lynch’s camera penetrates a perfectly-green lawn to show a hoard of insects fighting beneath the grass, viewers realize that Lumberton, like many other “perfect” neighborhoods, contains two separate worlds: one of rosy optimism, and another of animal instinct.

It’s no coincidence that during the dark sequences, the performances, and the writing, are much more realistic than the alternate reality of the Lumberton-Sandy-chicken-walk utopia. This is precisely the point — to prove how artificial our ideas of nostalgic America really are. Lynch wants us to acknowledge that a darker side exists, and we can’t just escape it by moving to the suburbs.

“He wants to set you up,” Gene Siskel said. “He’s a director. And he wants to play you — like all the great directors want to do — he wants to play you like a piano, which is have you smile and then swing you right into some depression.”

This notion of “playing the audience” gives Lynch license to alter the idea of “authenticity” itself. Those who poke fun at the inauthenticity of Blue Velvet have become the butt of its joke. Like the conniving artist he is, Lynch actually invites you to criticize the hokeyness, so he can sit back and laugh at you for not getting it. Notice the way Detective Williams responds to Jeffrey showing him the ear, taking one glance and saying, “Yes, that’s a human ear alright.” His voice never raises a decibel above monotone.

Notice also how melodramatic the music becomes when Sandy first steps out of the darkness and into the light for a sidewalk stroll straight from the ’50s teen handbook. It’s a mockery of the love interest archetype of classic Americana. From this alone, we should realize we’re entering a larger-than-life, highly-stylized world.

Later, when their car pulls up outside a church, Jeffrey gives an over-the-top delivery: “Why are there people like Frank? Why is there so much trouble in this world?” With a pipe organ playing in the background, Sandy recounts a dream about robins coming to bring light to a world of darkness, and that there will be “trouble until the robins come.”

This prophecy is later fulfilled as the light of Lumberton returns and Jeffrey and Sandy stare at a mechanical-looking robin, tilting its head to the side in robotic fashion. Hopper called it one the film’s wonderful little quirks, but it also carries meaning. (F) It’s phony just the way the waving fireman is phony. The question becomes whether Lynch is leaving us on a note of optimism, saying love is the only way out of the madness, or if he’s saying humans are outwardly phony and are actually most real in their compulsive, fetishistic, emotionally-confused state?

No matter your take, the message is that the darkness is never far. It’s barely even beneath the surface, as ordinary as a guy yelling, “Hey Babe!” at Sandy in town. Jeffrey just don’t realize it until it’s too late, lying face down in the mud in a Lumberton lumber yard. What a far cry from the pristine Lumberton billboards at the outset of the film.

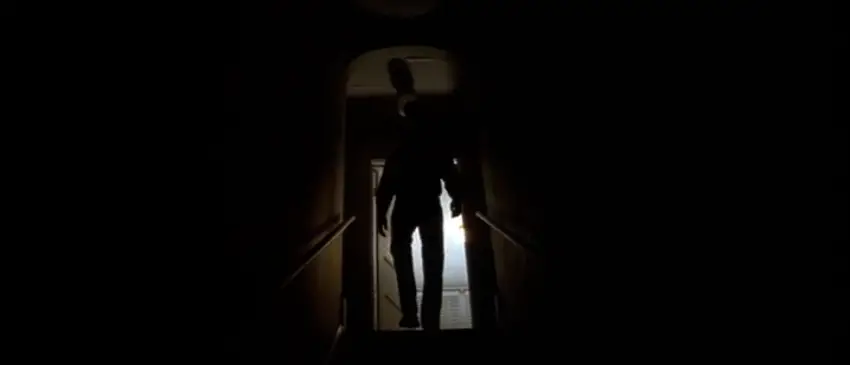

Innocence Lost: The Noir Night Journey

At the start of the film, Jeffrey is oblivious to this sinister underbelly. His false confidence, paired with a driving curiosity, makes him the perfect hero in what is arguably one of the finest examples of neo-noir. Like his genre’s predecessors, Jeffrey embarks on a classic night journey the minute he descends the stairs in silhouette and exits into an entirely Lynchian world. It reminds me of the shot of Faye Dunaway descending the stairs to join Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), only in a much darker world. As Travers writes, he “drops through the rabbit hole of Norman Rockwell America.” (B)

As Jeffrey comes down the stairs, note how his mother and aunt sit on the couch watching a violent noir crime film. Outwardly, they have sought safety in a perfect suburban neighborhood, but inwardly, they desire this violent TV content. Lynch purposely holds on the TV, showing a man climbing the stairs in suspense, because it mirrors Jeffrey’s own descent down the stairs, showing he’s about to enter the violent world his loved ones crave from their televisions.

As Jeffrey comes down the stairs, note how his mother and aunt sit on the couch watching a violent noir crime film. Outwardly, they have sought safety in a perfect suburban neighborhood, but inwardly, they desire this violent TV content. Lynch purposely holds on the TV, showing a man climbing the stairs in suspense, because it mirrors Jeffrey’s own descent down the stairs, showing he’s about to enter the violent world his loved ones crave from their televisions.

After exiting his home, watch how he and Sandy walk in and out of pockets of light caused by intervals of darkness between homes. The symbolism here is genius, as between the “light” of these suburban homes exists a foreboding darkness that is soon to engulf these two innocents.

The curiosity of youth will lead to a loss of innocence, and Jeffrey and Sandy aren’t the first. Detective Williams says he was just like Jeffrey as a kid, full of curiosity, and that’s what got him into law enforcement. However, when Jeffrey says, “That’s great,” the detective responds, “It’s also horrible.”

When you dig, all you get is dirty. And the deeper we dig into others’ dark sides, the more we learn about ourselves. For Jeffrey, the revelation is a nightmare. At one point, Sandy tells him, “I don’t know if you’re a detective or pervert,” and we spend the rest of the film exploring that dichotomy. Jeffrey himself doesn’t know the answer until the moment he has sex with Dorothy and, at her request, beats her for arousal. It forces Jeffrey to admit Frank was right when he said, “You’re like me.” Realizing he’s capable of the exact same evil, he sobs uncontrollably. They’re tears for himself and tears for humanity.

Voyeurism & Complicity

We as viewers are just as guilty in all this as Jeffrey. Like Jeffrey’s mom and aunt watching the crime show on TV, we willingly partake in Jeffrey’s journey with him, thanks to POV shots from Jeffrey’s perspective, looking out of a closet door to see horrendous sex acts.

At this point, we righteous case-solvers have been tricked into an uncomfortable voyeurism. We have been so intent on figuring out this mystery, on wanting to find out more, that we have been exposed as closet perverts. What’s the consequence? We’re forced to witness the most horrific rape scene in movie history, worse than Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972).

WARNING: This video may be the most disturbing scene you’ll ever see:

Shocking does not even begin to describe it. In fact, it was the brutality of this scene alone that drove Ebert to his negative review. He complained that Rossellini was “degraded, slapped around, humiliated and undressed in front of the camera.” (C) Gene Siskel took the opposite stance, saying the film did for him what Psycho (1960) had: “Eyes open and oh my God, we’re really getting in over our heads.” (D)

A Surrealist Painter’s Touch

You’ll note the above rape scene ends with Frank saying, “You stay alive baby. Do it for Van Gogh.” This is clearly a reference to the chopped off ear of Dorothy’s husband, whom Frank holds hostage.

The Van Gogh references are fitting, as Lynch’s own previous career was as a painter. His films are proof, showing an understanding of textures and moods, lights and darks, and the power of a consistent color palette. His painterly background no doubt helped his collaboration with cinematographer Frederick Elmes (Wild at Heart).

These gorgeous compositions can also be symbolic, like the POV wide shot of Dorothy’s apartment. Not only do the living room purples please us aesthetically, the decision to hold the shot as Dorothy ventures down a side hallway emphasizes her emotional “smallness,” while keeping emphasis on the couch, where Jeffrey finds a clue.

These gorgeous compositions can also be symbolic, like the POV wide shot of Dorothy’s apartment. Not only do the living room purples please us aesthetically, the decision to hold the shot as Dorothy ventures down a side hallway emphasizes her emotional “smallness,” while keeping emphasis on the couch, where Jeffrey finds a clue.

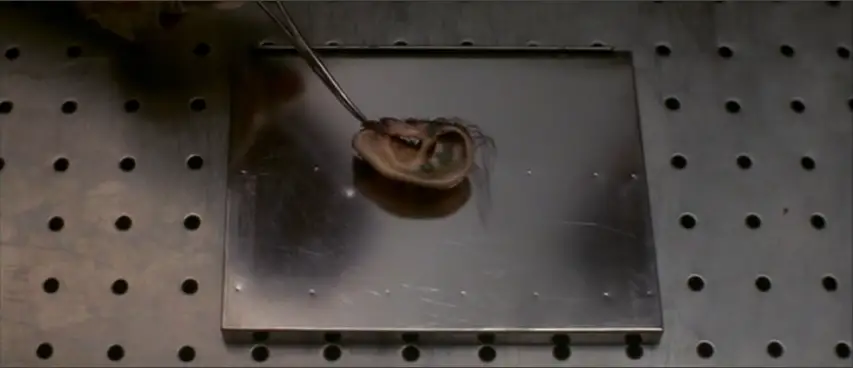

We must also remember Lynch was a surrealist painter, thus painting his Blue Velvet canvas with scenes of experimental, heightened reality. Such an approach has earned Lynch the unofficial title of “king of the weird,” but he’s actually just one in a long line of experimental filmmakers. In fact, the ant-covered ear in Blue Velvet is an homage to the ant-covered hand in the classic film Un Chien Andalou (1928), co-created by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali.

We must also remember Lynch was a surrealist painter, thus painting his Blue Velvet canvas with scenes of experimental, heightened reality. Such an approach has earned Lynch the unofficial title of “king of the weird,” but he’s actually just one in a long line of experimental filmmakers. In fact, the ant-covered ear in Blue Velvet is an homage to the ant-covered hand in the classic film Un Chien Andalou (1928), co-created by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali.

Such surrealism comes out in many forms in Blue Velvet, from slow-mo sequences to stretched faces to characters disappearing from the frame, all set animalistic roars, revving engines and some of the wildest sound design you’ve ever heard. In this ream, Lynch equates Frank with flames, forcing Dorothy to turn off a lamp and light a candle before the rape, saying, “Now, it’s dark.” The flame image returns multiple times in Jeffrey’s dreams, until finally a lamp goes out as Frank is extinguished. What a fitting metaphor for Frank, the kind of guy who lights up the room, burns hot and flames out.

Parallelism & Familiar Image

The flame. The light. The dream catcher. “Now, it’s dark.” They’re all examples of repetition. Throughout the film, Lynch demonstrates a mastery of familiar images, whether it’s the pointy propeller hat of Dorothy’s son, the yellow suit of the Yellow Man, or the ever-present logs of the town’s industrical core. Even the dialogue proves cyclical, like Frank saying a love letter from him is a “bullet from a gun,” to the song “Love Letters” on the soundtrack as we actually see bullets fly.

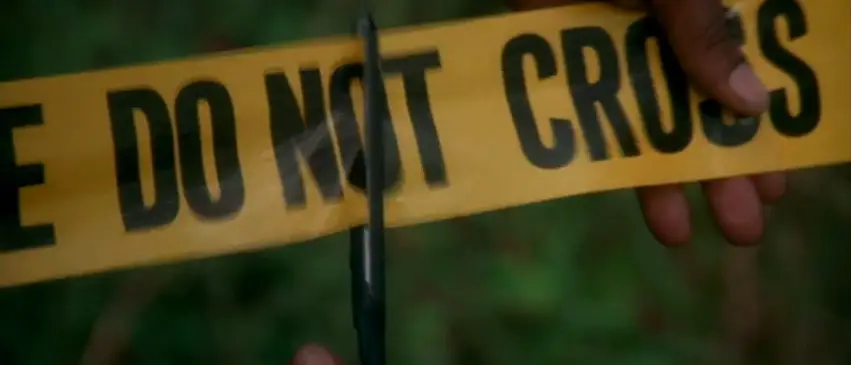

One of my favorite familiar images is that of scissors, from a coroner saying the ear was cut off with scissors to Lynch “cutting” to a shot of scissors snipping police tape. It’s more than just a cool jump cut; it’s our first hint that someone within the police department is in on the crime. The motif of returns horrifically as Frank appears to takes a pair of scissors to Dorothy’s genitals.

The repetition not only applies to props, it also applies to entire set pieces. Take, for instance, Jeffrey’s recurring trips up and down the stairwell of Dorothy’s apartment building.

Most famously, there’s the parallelism of the ear, which Lynch called “an opening into another world.” (F) While the camera plunges into the severed ear as Jeffrey begins his “night journey,” it pulls out of Jeffrey’s own ear during the film’s resolution. Perverts could make gross connections to Kubrick’s notion of the “old in/out.” I just think it’s great parallelism.

Finally, Lynch provides the bookends of flowers, firemen and dissolves from a blue sky to blue velvet curtain. From start to finish, curtain to curtain, the film is entirely under Lynch’s control. He absolutely deserved his Oscar nomination for Best Director, losing to Oliver Stone for Platoon (1986). It remains the only Academy Award nomination of his career, but when he finally won the Palm d’Or for Wild at Heart (1990), I’ve got to think it was the culmination of momentum building since Blue Velvet.

Enveloping Music

Fitting for a film about a sliced-off ear, Lynch demonstrates a great ear for music. How can a movie be so grotesque and sound so angelic at the same time? The score makes us feel as though we’re floating through the entire film. It’s a phenomenal achievement by composer Angelo Badalamenti, collaborating with Lynch for the first time and sparking a great relationship that led to Wild at Heart (1990), Twin Peaks (1990), Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Dr. (2001).

Badalamenti has us from the first note. His brooding score over a waving blue velvet curtain is as hypnotic as any opening credit sequence since Vertigo (1958).

From there, Lynch moves right into Bobby Vinton’s deceptively cheery title song. As previously stated, it was one of the three things — along with red lips and green lawns — that sparked the film’s creation, and it’s easy to see why. Few songs capture the elusive dreams of Mr. Lonely better than “Blue Velvet,” which topped the Billboard charts in 1963.

The next time we hear Vinton’s song, it’s being sung by Dorothy on stage, bathed in blue light and wearing blue eye shadow, red lipstick and a dark wig to hide behind. I’ve got to think this scene inspired the “Silencio” scene in Mulholland Dr.

After this disturbing take on Vinton, Lynch goes to work on another “golden oldie.” In perhaps the weirdest scene of the film — and by that I mean my favorite — Dean Stockwell lip-syncs Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” to a room of fat women, using a work lamp as a microphone. The son of Prince Charming in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Stockwell was a holdover from Old Hollywood, having worked with legends like Orson Welles and Gene Kelly. His appearance in both Blue Velvet and Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984) vaulted him to an Oscar nomination for Married to the Mob (1988) and a starring role on TV’s Quantum Leap (1989).

Minutes later, Lynch uses the same Orbinson song to create another image I have yet to shake — Frank reciting “candy colored” lyrics as he applies lipstick to his own lips, transfers it to Jeffrey with a kiss, then proceeds to beat him down. Frank’s entourage (including Brad Dourif from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) puts “In Dreams” on the cassette player of Frank’s car, prompting a fat woman to belly dance on the roof.

After all these re-workings of pop music classics, we finally get an original work, “Mysteries of Love.” With music by Badalamenti and lyrics by Lynch himself, the song brings an overpowering emotion that gives the film its transcendent feel into the end credits.

Pop Culture

Just like Blue Velvet took pop culture staples (Bobby Vinton, Roy Orbison) and made them its own, countless works have referenced Blue Velvet since. Lynch himself created the Golden Globe-winning Twin Peaks (1990), which is more or less a Blue Velvet spinoff, featuring a murder mystery set in a similar Northwest town, starring McLachlan with music by Badalamenti.

In A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), screenwriter Frank Darabont and Wes Craven reference Dennis Hopper by having Freddy Krueger say, “Where’s the f*ckin’ bourbon?” In Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Jessica Rabbit plays a Dorothy Vallens type character, taking the stage against a blue velvet curtain backdrop and even quoting Dorothy’s line, “He used to make me laugh.”

In Robocop 2 (1990), a scientist named Frank develops a drug called “Blue Velvet.” Quentin Tarantino references the “severed ear” in the famous scene from Reservoir Dogs (1992). And in Clerks (1994), Jay and Silent Bob quote Hopper’s, “I’ll f*ck anything that moves!”

The most obvious reference comes in the stoner comedy Bio Dome (1996), where Pauley Shore and Stephen Baldwin do their own hits of Nitrous Oxide, saying, “Dennis Hopper, Blue Velvet!”

The film even had an effect outside the TV and film culture. Hopper’s shouts of, “Heineken? F*ck that sh*t!” actually galvanized a generation to reconsider Pabst Blue Ribbon, and today it’s one of the most popular Hipster beers.

Final Thoughts

Such lowbrow pop culture references are almost an insult to the depth of Lynch’s goals with Blue Velvet. Then again, perhaps they play right into his notion of contrasting pop camp with disturbing, gritty realism. Love it or hate it, Blue Velvet sticks with you long after its velvet curtain drops. And for anyone who says, “David Lynch movies are just too strange for me,” Lynch provides the perfect rebuttal here in Blue Velvet: “It’s a strange world, isn’t it?”

David Thomson said it was the last transcendent movie experience he’s had in theaters, save maybe The Piano (1993). He says Blue Velvet offered him “a kind of passionate involvement with both the story and the making of a film, so that [he] was simultaneously moved by the enactment on screen and by discovering that a new director had made the medium alive and dangerous again.” (A)

There’s also evidence that Roger Ebert is open to giving the film a second chance. After the death of his long-time partner Siskel, Ebert expressed an open mind on Ebert and Roeper, saying, “I still feel badly about how Rossellini was treated (and so does she, judging by her autobiography). But Lynch is a good director and I should re-visit the film.” (E)

The line between masterpiece and trash is understandable. The film thrusts you into the deep end, both with its subject matter and its ability to challenge your notions of film-watching. It stole my film innocence. I felt dirty, guilty, and stupidly naive watching it. But for anyone still hesitant to see this movie, or dreading to return to it, I’ll tell you the same thing Jeffrey tells Sandy: “There are opportunities in life for gaining knowledge and experience. Sometimes it’s necessary to take a risk.”

That risk may not pay off the first time you see it. You will realize it one day, weeks, perhaps years later, as you walk outside on a routine day and see your own robin. A haunting rendition of Bobby Vinton will begin in your head. Your mind will wander, conjuring fears of the dark underworld around you, and arousing suspicions as to which of your peers may be a Frank Booth or a Dorothy Vallens, or even worse, how much of a Frank Booth or Dorothy Vallens is within you. And when the epiphany is over, you will shake your head, snap out of it, and look back at the robin and smile. But as you walk away, you know that you’ll never look at the world the same.

![]()

Citations

CITE A: David Thomson, Film Dictionary

CITE B: Peter Travers, 100 Maverick Movies, Rolling Stone magazine

CITE C: rogerebert.com

CITE D: Siskel & Ebert at the Movies 1986 (from DVD special features)

CITE E: http://74.125.113.132/search?q=cache:xYBlUxuwf1cJ:bventertainment.go.c om/tv/buenavista/ebertandroeper/chat/transcript-ebert-070802.html+eber t%2Btranscript%2Bblue+velvet&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=ca

CITE F: Mysteries of Love documentary, DVD special features