Director: Billy Wilder

Producer: Charles Brackett (Paramount)

Writers: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder, D.M. Marshman Jr. (screenplay)

Photography: John F. Seitz

Music: Franz Waxman

Cast: William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Erich von Stroheim, Nancy Olson, Jack Webb, Cecil B. DeMille, Hedda Hopper, Buster Keaton, Anna Q. Nilsson, H.B. Warner, Fred Clark, Lloyd Gough, Franklyn Farnum, Larry J. Blake, Charles Dayton

![]()

Introduction

“There’s nothing tragic about being 50. Not unless you try to be 25!”

Call it Billy Wilder’s best; a cautionary tale of celebrity’s dangerous price; and Hollywood’s most daring, cynical and honest look at itself. Sunset Blvd. held such a controversial mirror up to the film industry that the original script had to be printed under the code name A Can of Beans. When MGM chief Louis B. Mayer saw the picture, he stormed out of the screening and screamed at Wilder, “You bastard! You have disgraced the industry that made you and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” (A)

Perhaps Wilder had bitten the hand that fed him, but they were necessary bite marks. So often we see a glorified Hollywood with glamorous red carpets, deep wallets and adoring fans. Rarely do we get a glimpse into the price of fame, until that price has tragically been paid, marked by blood and the flashbulbs of a media circus.

What lies between the glory and the fall? What happens mentally and emotionally to movie stars once they pass their prime and are rejected by the business that created them? What do they do as they’re relegated to spending day after day in the wide-open loneliness of their huge Beverly Hills mansions? This is precisely what Wilder captures in Sunset Blvd., the quintessential Hollywood movie and the quintessential anti-Hollywood movie, poignantly arriving at the tail-end of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

![]()

Plot Summary

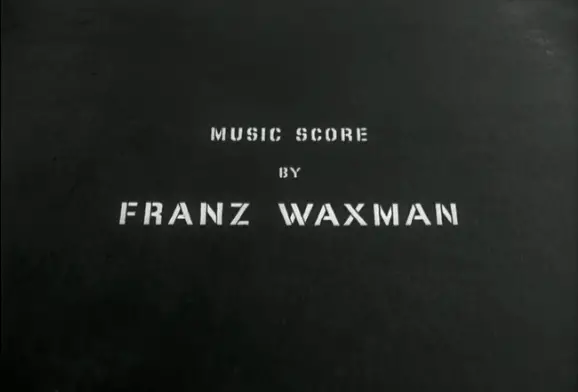

The film opens with one of the coolest images in movie history, that of reporters and police rushing to find our main character, Joe Gillis (William Holden), floating face-down in a swimming pool. His spirit hovers over the entire picture, narrating the path to his demise. The idea of having your hero dead before the picture even starts, then serving as narrator, came a full 49 years before Kevin Spacey did it in American Beauty (1999), whose director Sam Mendes listed Sunset Blvd. one of his Top 10 favorite movies.

Gillis calls himself“nobody important, really, just a movie writer with a couple of B-pictures to his credit.” He’s a starving artist, pounding out scripts on his typewriter but unable to sell them. When financiers come to repossess his car, he evades them down Sunset Blvd., pulling into a decaying Hollywood estate to hide, clueless to the fact that he has just stepped into the manhole that’s sealed his fate.

The mansion belongs to Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), a former star of the silent era, who remains in denial of her bygone stardom. Even creepier is Desmond’s ex-director, ex-husband and now butler, Max von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim), who facilitates her fantasy by sending fake fan mail, too heartbroken to tell her otherwise. As Gillis says, “Poor devil. Still waving proudly to a parade that had long passed her by.”

The mansion belongs to Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), a former star of the silent era, who remains in denial of her bygone stardom. Even creepier is Desmond’s ex-director, ex-husband and now butler, Max von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim), who facilitates her fantasy by sending fake fan mail, too heartbroken to tell her otherwise. As Gillis says, “Poor devil. Still waving proudly to a parade that had long passed her by.”

A midnight funeral service for Norma’s pet monkey would have been most people’s cue to leave, but Gillis decides to stay when he’s offered to finish Norma’s script, Salome, based on the Oscar Wilde work. The two become partners: her chance for a comeback and his way of supporting himself. On the surface, it’s not a bad deal for Gillis. He’s given a room for free and treated to the best luxuries money can buy. As a suit salesman tells Gillis, “As long as the lady’s paying for it, why not take the Vicuna?”

A midnight funeral service for Norma’s pet monkey would have been most people’s cue to leave, but Gillis decides to stay when he’s offered to finish Norma’s script, Salome, based on the Oscar Wilde work. The two become partners: her chance for a comeback and his way of supporting himself. On the surface, it’s not a bad deal for Gillis. He’s given a room for free and treated to the best luxuries money can buy. As a suit salesman tells Gillis, “As long as the lady’s paying for it, why not take the Vicuna?”

Soon enough, though, he realizes just how deep he’s in, so deep that loving Norma has become almost a contractual obligation. As Gillis says, “It’s a very simple set up. Older woman who’s well to do, younger man who’s not doing too well. Can you figure it out yourself?” Cut throat bigalow, male gigolo.

Of course, Gillis can only muster the pretense of feelings for Norma, as his heart really belongs to Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), a lowly script reader on the Paramount lot. At nights, he sneaks out to the studio and works on a new script with Schaefer, who falls for Gillis despite being engaged.

In love with Betty, Gillis is ready to leave his trap forever, but Norma’s suicidal tendencies guilt him into staying. Finally, Norma discovers the script he’s been working on, Untitled Love Story, and the thought of being replaced by a younger girl is enough to put Gillis face first into that pool.

In love with Betty, Gillis is ready to leave his trap forever, but Norma’s suicidal tendencies guilt him into staying. Finally, Norma discovers the script he’s been working on, Untitled Love Story, and the thought of being replaced by a younger girl is enough to put Gillis face first into that pool.

![]()

Screenwriting Gold

The beauty of the script is that it’s not a question of what’s going to happen, but how it’s going to happen. We know from the start that a big star has killed Gillis and we watch to see how it unfolds. For this out-of-order structure, Sunset Blvd. joins Citizen Kane (1941) and All About Eve (1950) as the three most important American scripts in pioneering the non-linear format that would eventually make Pulp Fiction (1994) possible.

It was also one of the first scripts with a modern edge to it, a unique bite and a dark humor that showed Wilder years ahead of his time (perhaps made that way when his family was murdered in Nazi concentration camps). Above all, it was a testament to screenwriting itself, as Gillis says, “Audiences don’t know somebody sits down and writes a picture. They think the actors make it up as they go along.” Thus, the Writers Guilds’ ranked Sunset Blvd. the No. 7 Greatest Screenplay of All Time.

It was also one of the first scripts with a modern edge to it, a unique bite and a dark humor that showed Wilder years ahead of his time (perhaps made that way when his family was murdered in Nazi concentration camps). Above all, it was a testament to screenwriting itself, as Gillis says, “Audiences don’t know somebody sits down and writes a picture. They think the actors make it up as they go along.” Thus, the Writers Guilds’ ranked Sunset Blvd. the No. 7 Greatest Screenplay of All Time.

Any writer would love to have even one line of his dialogue make the AFI’s 100 Movie Quotes. Sunset Blvd. has two; both in the Top 25. How ironic, considering Norma herself despised dialogue: “We didn’t need dialogue, we had faces.” Ranking No. 24 is that marvelous exchange when Gillis realizes who Norma is: “You’re Norma Desmond, you used to be in silent pictures, you used to be big!” and Norma’s response: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.”

Ranking all the way at No. 7, higher than “You talkin’ to me?” and “May the force be with you,” is the film’s haunting final quote: “Alright, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.”

Still, the more you watch it, you settle in on the more obscure lines: “If ever there was a place to stash away a limping car with a hot license number;” “You don’t yell at a sleepwalker; he may fall and break his neck;” and “The poor dope! He always wanted a pool. Well, in the end, he got himself a pool; only the price turned out to be a little high.”

When you watch Sunset Blvd., you should really try to step back for a moment and imagine yourself the writer of the film. Could you come up with that many sizzling descriptions without sounding clunky? Better yet, could you have sculpted characters of this complexity, a premise this intriguing, a theme this powerful? Don’t feel bad. Few could ever write that well. A screenwriting Oscar was the only suitable finale for Wilder and Charles Brackett, who made Sunset Blvd. their last collaboration after 14 years of sparkling scripts like Ninotchka (1939) and Ball of Fire (1941). (A)

Sharing a writing credit with D.M. Marshman Jr., Sunset Blvd. was inspired by an unsolved Hollywood case where silent-film director William Desmond Taylor, lover of actress Mabel Normand, was murdered in 1922. Combining their names, they got “Norma Desmond.” (E) More inspirational than this single case was the overall state of the film industry in 1950. Sound and Technicolor had ruptured many a career. As Norma says, “There was a time in this business when they had the eyes of the whole wide world. But that wasn’t good enough for them, oh no. They had to have the ears of the world, too. So they opened their big mouths and out came talk, talk, talk! … You’ll make a rope of words and strangle this business! But there’ll be a microphone there to catch the last gurgles, and Technicolor to photograph the red, swollen tongues!”

“Sunset Blvd. came about because Wilder, Marshman and I were acutely conscious of the fact that we lived in a town [that] had been swept by a social change as profound as that brought about in the Old South by the Civil War,” said Brackett. “Overnight, the coming of sound brushed gods and goddesses into obscurity. We had an idea of a young man, happening into a great house where one of the ex-goddesses survived. At first, we saw her as a kind of horror woman – an embodiment of vanity and selfishness. But as we went along, our sympathies became deeply involved with the woman who had been given the brush by 30 million fans.” (A)

![]()

Gloria Swanson: The Real-Life Norma Desmond

For such a complex role, Wilder had originally wanted Mae West, who was canned after she wanted to rewrite her own lines. Silent queen Mary Pickford also declined the part, not wanting to look like a decaying star. From a historical standpoint, it may have been most interesting to see Pickford in the role, as she was the bigger star, the wife of Douglas Fairbanks and co-founder of United Artists. But from a performance standpoint, I can’t imagine anyone other than Swanson; the decadent way she moves, the delayed manner in which she speaks, the delusional eyes and the fear hidden just beneath the surface.

I suppose some may be annoyed by her “feverish” over-the-top show. Scholar David Thomson says it “provides a telling study in the way mime had so trained actors and actresses that when sound arrived they could not stop shouting.” (C) To me, the performance works despite its trained forcefulness, though my affection may stem from the fact that Desmond recalls more than one drama teacher from my own past. Fan or not, it’s a performance for the history books. Premiere magazine voted Norma Desmond the No. 31 Greatest Movie Character of All Time and Swanson’s the #69 Greatest Performance of All Time.

I suppose some may be annoyed by her “feverish” over-the-top show. Scholar David Thomson says it “provides a telling study in the way mime had so trained actors and actresses that when sound arrived they could not stop shouting.” (C) To me, the performance works despite its trained forcefulness, though my affection may stem from the fact that Desmond recalls more than one drama teacher from my own past. Fan or not, it’s a performance for the history books. Premiere magazine voted Norma Desmond the No. 31 Greatest Movie Character of All Time and Swanson’s the #69 Greatest Performance of All Time.

Shame on Pickford, who didn’t have the guts to play it. And bravo to Swanson, who knew when she took the role that it would be a mockery of everything she had once been: Hollywood’s highest paid actress before retiring in 1934 and attempting a comeback in 1941. (C) She knew that with this new role she would go down as one of cinema’s greatest movie monsters, a pathetic creature trying to look young while she was so old, with all that makeup, all those outfits and all those skin treatments on her face. (D)

With nothing to lose, she divorced her husband, moved to Hollywood, played the part, and gained her first Oscar nomination in 21 years. When she lost to newcomer Judy Holliday’s spectacular debut in Born Yesterday (1950), Swanson reportedly said, “Why couldn’t you have waited till next year?” (G)

![]()

William Holden

The film was perhaps even more helpful to the career of Holden, who had fallen off the map since his breakthrough in Golden Boy (1939). The part of Gillis was originally written for Monte Clift, who first accepted, then turned it down, making way for Holden to revive his career. Sunset Blvd. was his first of three Oscar-nominated performances, and by the time he appeared in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), he was the highest grossing actor in Hollywood. In a way, he had achieved the very Hollywood stardom Gillis had so desperately desired.

Co-star Nancy Olson called him the “lynchpin” of the film, his swagger the only that could have pulled off Wilder’s attitude in 1950. Itt says something that two of the WGA’s Top 10 Screenplays starred Holden. When he won his Oscar for Stalag 17 (1953), he need only take the stage, say “Thank you,” and leave, for he had already left a string of slick lines on screen.

![]()

Erich von Stroheim

With far fewer lines, but just as much presence, is Erich von Stroheim, who earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor and threatened to sue Paramount for the insult to his stature. (G) That’s because Von Stroheim fancied himself to be more than a supporting actor. He was a master filmmaker, the most dogged director in the history of movies, more than Orson Welles, his creative vision crushed by his studio superiors. It’s sad to think we’ll never know the complete artistic vision of a man of so gifted, because so many of his films no longer exist in their original forms.

Indeed, Von Stroheim was independent before independent was cool, and he paid a price for it. In 1921, his Foolish Wives was severely cut by Universal, and in 1922, he was kicked off Merry-Go-Round (1922) for disputes with studio head Irving Thalberg. He next embarked on his most ambitious project, the 10-hour silent masterpiece Greed (1924), but that, too, was chopped down to roughly a quarter of its original length. The Wedding March was another disaster, where he was removed from the director’s chair once more and the film was released only briefly in Europe. (C)

Thus, most people haven’t the films he made, but rather the ones he acted in later in his career, masterpieces like Renoir’s La Grande Illusion (1937) and, yes, Sunset Blvd. His casting as Norma’s enabler Max was obviously inspired by the fact that he had actually directed Swanson in those real-life silent pictures. How wonderfully cruel of Wilder to make both Von Stroheim and Swanson watch a scene from their unfinished, silent-era bust Queen Kelly (1928), which never was released in the U.S. and lost both of them tons of money as co-producers. While shooting Kelly, Swanson reportedly called her lover and co-producer Joe Kennedy (father of JFK) and said you’ve got to come out here, there’s a madman directing this picture! (F)

In truth, Von Stroheim was a man of extraordinary insight and knew exactly what he was getting into with Wilder. He knew it was his own troubled story that would lend Sunset Blvd. its authenticity, and when Wilder finally let him get behind the camera for the film’s final shot, it was the sad fulfillment of a career so jaunted.

In truth, Von Stroheim was a man of extraordinary insight and knew exactly what he was getting into with Wilder. He knew it was his own troubled story that would lend Sunset Blvd. its authenticity, and when Wilder finally let him get behind the camera for the film’s final shot, it was the sad fulfillment of a career so jaunted.

![]()

Wax Works & Familiar Faces

While Swanson and von Stroheim played shades of their former selves, we also get a cast of familiar faces playing themselves in cameo appearances. Most memorably is Cecil B. DeMille as the famous Paramount director, the Spielberg of his day, in the middle of shooting Samson and Delilah (1949).

You’ll also see a whole slew of silent stars when Norma invites her old friends over for a game of bridge. There’s the indelible Buster Keaton of Sherlock Jr. (1924) and The General (1927) fame; Anna Q. Nilsson, Babe Ruth’s co-star in The Babe Comes Home (1927); and H.B. Warner, Swanson’s co-star in Zaza (1923), DeMille’s choice for Christ in King of Kings (1927) and Mr. Gower in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Gillis calls them “the wax works,” frozen figures of a bygone era, who could just as easily inhabit Madame Tussaud’s.

When the wax finally hits the fan, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper appears as a member of the media swarm, ready to spin Norma’s demise into headlines.

There’s even a scene where Gloria Swanson does her best Charlie Chaplin impression. It’s yet another display of Norma Desmond stuck in the silent era.

![]()

Soundtrack

How appropriate that this tale of Hollywood wax figures be scored by a fellow named Waxman? After getting his first break as an orchestrator on The Blue Angel (1930) in Germany, Waxman joined his good friend Wilder in escaping Hitler and moving to Hollywood. There, Waxman exploded with his score for Bride of Frankenstein (1935), leading up to Sunset Blvd., which earned his first of two Oscars in a row, followed by A Place in the Sun (1951), making him the first in history to do so.

His score for Sunset Blvd. gives a bee bop motif to Gillis, a tango for Norma (that symbolically deteriorates as the film progresses), even a waltz parody of “Paramount on Parade” in the love scene between Gillis and Schaefer on the Paramount lot. (F) Voted #16 on AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores, Waxman’s strings provide the crucial eerie emptiness, and you can see why Hitchcock recruited Waxman a handful of times, particularly on Rebecca (1940), where Waxman’s music traps Mrs. Danvers in Manderley the same way they do Ms. Desmond in her estate.

His score for Sunset Blvd. gives a bee bop motif to Gillis, a tango for Norma (that symbolically deteriorates as the film progresses), even a waltz parody of “Paramount on Parade” in the love scene between Gillis and Schaefer on the Paramount lot. (F) Voted #16 on AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores, Waxman’s strings provide the crucial eerie emptiness, and you can see why Hitchcock recruited Waxman a handful of times, particularly on Rebecca (1940), where Waxman’s music traps Mrs. Danvers in Manderley the same way they do Ms. Desmond in her estate.

![]()

Haunting Visuals

If Waxman’s score lays the foundation for that emptiness, it’s physically realized by the Oscar-winning Set Direction. The derelict mansion is the former home of J. Paul Getty, located at the corner of Irving and Wilshire. It was used again in the finale of Rebel Without a Cause (1955), where James Dean, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo walk around a drained pool where once William Holden floated.

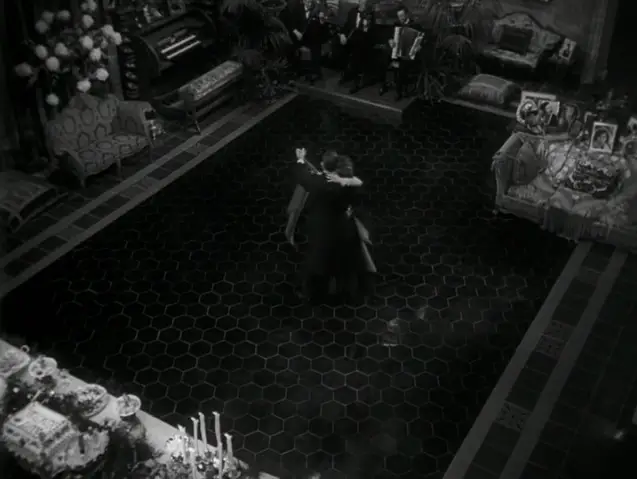

While the exteriors set the mood, it’s the interiors that earned the Set Direction gold. The vast emptiness of the mansion is most haunting when Gillis comes downstairs for the New Year’s Eve party, realizing he’s the only one there, joining Norma on an empty dance floor.

While the exteriors set the mood, it’s the interiors that earned the Set Direction gold. The vast emptiness of the mansion is most haunting when Gillis comes downstairs for the New Year’s Eve party, realizing he’s the only one there, joining Norma on an empty dance floor.

Critic Kim Newman says the Desmond mansion “evokes the lair of the Phantom of the Opera and Kane’s Xanadu, a huge close-up of white-gloved hands playing a wheezy pipe organ.” (D)

Indeed, there are times when no one is at the organ, but the wind blows through it and hums in the background. Beneath a haze of must (marble dust thrown in front of the camera), we see hoards of old pictures and antiques that serve as a time warp for visitors the minute they step in the door (as do the costumes by Edith Head). There’s even a projection screen built into the wall for nightly screenings of Norma’s old movies.

Indeed, there are times when no one is at the organ, but the wind blows through it and hums in the background. Beneath a haze of must (marble dust thrown in front of the camera), we see hoards of old pictures and antiques that serve as a time warp for visitors the minute they step in the door (as do the costumes by Edith Head). There’s even a projection screen built into the wall for nightly screenings of Norma’s old movies.

Connecting each and every room are doors without doorknobs, replaced by circular cut outs to prevent Norma from locking herself in a room and slitting her wrists. This woman must be deprived of the knobs, for she doesn’t even have a handle on her own sanity.

![]()

Wilder: Writer vs. Director

Billy Wilder was clearly one of the best writer-directors of all time, though he leaned more on his writing than directing. While he won an Oscar for his script, he lost Best Director to All About Eve’s Joseph Mankiewicz.

“There is a moment in Sunset Boulevard where William Holden’s interior monologue … mentions the childlike handwriting of the Gloria Swanson character. We do not see that writing. It is a writer’s ploy, astonishingly unadapted to the medium,” scholar David Thomson writes. “That is typical of Wilder. He outlines characters on paper — in dialogue, setting and situation — rather than in revealed behavior. Very often in his films, the actual images are incidental to the ‘facts’ of narration and dialogue. … The house in Sunset Blvd. bulges with detail that is all referred to in the script but that is never more than a gesture at plausible atmosphere.” (C)

Meanwhile, critic Kim Newman praises Wilder’s telling details, like the scene where Norma visits Paramount: “Cecil B. DeMille gently reminds Norma that the picture business has changed, but Wilder concludes his scene by having the camera note his polished riding boots and absurdly outdated on-set strut.” (D)

When you have a director writing his own scripts, the crossover is hard to separate out. Take the opening scene. The script describes the title “Sunset Blvd.” written on curb with dead leaves in the gutter. The symbolism is obvious, suggesting movie stars get kicked to the curb, left to die in Hollywood’s gutter. Who’s to say Wilder wasn’t thinking dictatorially as he wrote the script?

A slightly different example comes from Holden’s introduction. The script describes corpses talking to each other in a morgue, but when preview audiences laughed, the studio insisted it be changed. Thus, it was Wilder the director who created a superior alternative: an underwater shot looking up at Holden’s floating body. In truth, the shot was actually done from above, looking down at a reflecting mirror at the bottom of the pool.

A slightly different example comes from Holden’s introduction. The script describes corpses talking to each other in a morgue, but when preview audiences laughed, the studio insisted it be changed. Thus, it was Wilder the director who created a superior alternative: an underwater shot looking up at Holden’s floating body. In truth, the shot was actually done from above, looking down at a reflecting mirror at the bottom of the pool.

I also must take issue with Thomson’s notion that Wilder “outlines characters on paper — in dialogue, setting and situation — rather than in revealed behavior.” Your honor, I present the scene by the pool, where Norma dries off Gillis by wrapping a towel around his neck, right next to his future watery grave. (E)

![]()

Shadows & Mirrors

The living space is beautifully realized by 9-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer John F. Seitz, who also shot Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) and The Lost Weekend (1945). Together, Seitz and Wilder express a Gothic vision that doubles as film noir, painting Norma as the femme fatale and Gillis as the morally-corrupt hero doomed by his wanton self-confidence. Fittingly, Wilder surrounds them with shadows and mirrors, turning Sunset Blvd. into IMDB’s top Film Noir of All Time.

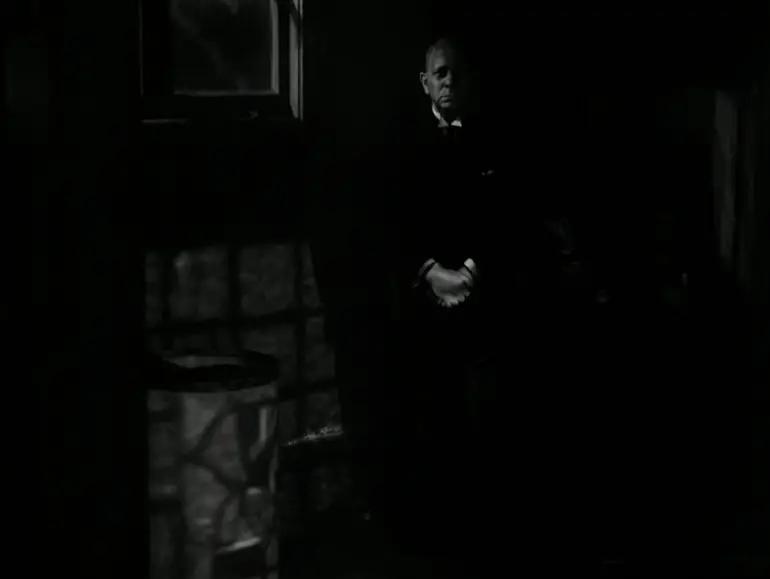

Wilder’s shadows include half-lit faces, signaling dual personas, competing loyalties and lurking danger.

The shadows also form jail-bar patterns, trapping Gillis in “that peculiar prison of mine.”

As for mirrors, another noir staple, Norma is quite literally stuck looking in the rear-view mirror.

Later, after Norma’s wrist cutting, Wilder shows her bandaged wrists in the foreground, as Holden crosses the room and speaks to Norma, shown only in a mirror, a reflection of her former self. Wilder then dollies with Holden as he kisses Norma on the forehead, sealing his fate with a kiss.

![]()

Watching Eyes

The haunting shadows and mirrors aren’t the only thing to makes audiences uneasy. Wilder also creates a motif of watching eyes that begins when Gillis first arrives at the Desmond mansion. As he surveys his surroundings, the camera slowly pushes in on Norma, who stares through the parted blinds with dark shades over her eyes.

The “watching eyes” theme returns in a later scene, where Norma says, “I wouldn’t let you [leave me for another girl].” As she exits through a pair of giant double doors, Wilder dollies in on the doorknob cutouts. The light switches off, creating the effect of two eyes watching.

The theme culminates with a creepy tilt up to see Norma looking down on Gillis, moments before she kills him.

![]()

Slow Motion Finale

Wilder’s final touch of genius comes in his slow-motion finale. The choice to shoot in slow-mo echoes Gillis’ description of the mansion being “stricken with a kind of creeping paralysis, out of beat with the rest of the world, crumbling apart in slow motion.” Surface-level emotion and deeply-layered themes collide as Norma makes her final cascade down the staircase, enfolded in her own dream, playing the role of princess to what she thinks are Max’s film cameras, when really they are newsreel devices documenting her demise.

The thematic implications are intense, as a former director (Max/Von Stroheim) directs his former star (Norma/Swanson) one last time, only now it’s a charade for the media with his beloved star headed to jail. Norma may say, “I’m ready for my close-up,” but Wilder doesn’t afford her that privilege, cutting instead to a long shot. (D) She fights for it nonetheless, approaching the camera to Waxman’s chilling strings, fingers awkwardly extended, grasping for an audience tragically out of her reach.

![]()

Pop Culture

The ripple effect of Sunset Blvd. was profound. The media theme inspired Wilder’s next project, Ace in the Hole (1951); the effect of “talkies” on silent stars inspired Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s Singin’ in the Rain (1952); and the self-critical look at Hollywood inspired Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful (1952).

The Gothic story of an aging actress inspired Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane (1962).

Andy Warhol produced a spoof, written and directed by Paul Morrissey, called Heat (1972).

in Brian DePalma’s Body Double (1984), a porn actresses dresses like Norma Desmond and imitates her final walk down the staircase.

In Robert Altman’s The Player (1992), a Hollywood producer (Tim Robbins) answers a phone call from someone who identifies himself as Joe Gillis. Mill asks his colleagues, “Anybody know who Joe Gillis is?” It’s a sad commentary on how many of today’s filmmakers don’t know the legends that created their business.

Robin Williams homages the film in Mrs. Doubtfire (1993), saying, “I feel like Gloria Swanson. I’m ready for my close-up, Mr. DeMille.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber created a Tony-winning stage version in 1993, starring Glenn Close as Norma.

In a 1996 episode of Seinfeld, Jerry retires from the movie bootlegging business by saying, “I am big. It’s the bootlegs that got small.”

Finally, David Lynch borrowed his street title and Hollywood themes for Mulholland Dr. (2001).

![]()

Legacy

How has Sunset Blvd. grown in stature since its release? In 1950, it couldn’t escape comparison to All About Eve (1950), both exposing the dark sides of their respective businesses: stage and screen. When it came time for the Academy Awards, Eve beat Sunset for both Best Picture and Best Director. Today, however, Sunset Blvd. has gotten its revenge, ranking No. 16 on AFI’s Top 100 Films, a full 11 spots higher than Eve. Wilder’s masterpiece appears on just about every best list known to man, including Entertainment Weekly (No. 28), Village Voice (No. 45) and TV Guide (No. 16). The film has found appeal among the masses (8.6 on IMDB) and filmmakers (No. 12 in the 2002 Sight & Sound Directors Poll).

The reason is that Sunset Blvd. is timeless, its themes just as relevant today as they were in 1950. Only now, fame’s double-edge sword has the sheen of a 24-7 media microscope. Is Norma’s pet monkey any different than Michael Jackson’s pet chimp Bubbles? Is her estate not its own Neverland Ranch? I share the sentiments of an astute IMDB poster who wondered how many stars there are today, sitting in their own decaying mansions, watching their old films on Turner Classic and fooling themselves that they are still stars?

Sunset Blvd. is a plea for sanity in an insane business, beautiful in its imagination, yet dangerous in its excesses. It’s a warning that if you want to live in the spotlight, you better keep your head on straight. Creative minds need occasional pinches of reality, that which are absent from Norma Desmond’s creed: “This is my life. It always will be. There’s nothing else. Just us. And the cameras. And those wonderful people out there in the dark.” Wilder’s masterpiece suggests the people in the dark have the better end of a deadly deal.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Variety, 7/19/93 (found through Writers Guilds’ Top 101 Screenplays site)

CITE B: Charles Brackett, “Putting the Picture on Paper,” WGA website

CITE C: David Thomson, New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE D: 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE E: Tim Dirks, AMC Filmsite.org

CITE F: Sunset Blvd. DVD “Making of” documentary

CITE G: The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History