Director: John Ford

Writers: Frank S. Nugent (screenplay), Alan Le May (novel)

Producer: Merian C. Cooper, Patrick Ford, C.V. Whitney (Warner Bros.)

Photography: Winton C. Hoch

Music: Max Steiner, Stan Jones

Cast: John Wayne, Jeffrey Hunter, Vera Miles, Ward Bond, Natalie Wood, John Qualen, Olive Carey, Henry Brandon, Ken Curtis, Harry Carey Jr., Antonio Moreno, Hank Worden, Beulah Archuletta, Walter Coy, Dorothy Jordan

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Screenplay

- The Duke’s Greatest Role

- Love Affair in Mise-en-Scene

- Lover’s Revenge

- Bricks and Chairs: Ethan’s Domestic Problem

- Lasting Scars: Ethan’s Racial Problem

- Parallels and Bookends

- Pop Culture

- Legacy

What binds such famous directors as Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Martin Scorsese? Their deep affection for John Ford’s The Searchers. Spielberg not only painted Ford’s Monument Valley onto a bed-sheet backdrop for a two-reel western in 7th grade, he watched The Searchers twice on location while shooting Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and faithfully recreated the orange glow invasion. (B) Lucas lifted an entire scene for Star Wars (1977), having Luke Skywalker come across his aunt and uncle’s burnt-down ranch much like John Wayne in The Searchers. And Scorsese had Harvey Keitel discuss the film in Who’s That Knocking at My Door? (1967) and take DeNiro to a movie theater to watch it in Mean Streets (1973).

It’s no coincidence that all three of these directors came up in the ’70s. To them, watching John Ford-John Wayne pictures was the stuff of ’50s childhood nostalgia. But as time passed, they came to realize just how much a masterpiece Ford had made, to the point that in 1979, the year Wayne died, New York magazine called it the “Super-Cult Movie of the New Hollywood.” (B)

“When I first saw The Searchers it was a terrific cowboy and Indian picture,” Spielberg said. “But as I got older and saw The Searchers numerous times, I realized that it had much deeper meanings than that.” (C)

I couldn’t agree more. For me, The Searchers was an “epiphany movie,” where the veil of “normal” movie-watching was lifted to reveal another way of seeing. I came to realize why Ford is so respected among academics. Why in 2002, MovieMaker Magazine called him one of the Top 5 Most Influential Directors of All Time. Why Entertainment Weekly voted him the #3 greatest of all time. And why Orson Welles always maintained that his Top 3 favorite directors were “John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.” (D)

What better way for average folks to have their own film theory awakening than a deceptively simple John Wayne western, the type of “Cowboy and Indian” flick your grandfather watched many a Saturday, not knowing that an entirely different language — the language of cinema — was masterfully at work?

Plot Summary

Adapted from Alan Le May’s 1954 novel and short story in the Saturday Evening Post, The Searchers is loosely based off an actual Comanche kidnapping of a young white girl in Texas 1836. (A) The film opens with the gray-coated Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) returning to his brother’s ranch for the first time since leaving to fight in the Civil War. Seeing as it’s now 1868 and the war ended in 1865, we determine that Ethan’s been missing for more than three years.

Nevertheless, the family is thrilled to see Ethan, including sister-in-law Martha (Dorothy Jordan, wife of producer Merian C. Cooper), who has a secret romantic past with Ethan; nephew Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), whom Ethan disrespects for being part Cherokee; and nieces Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (Lana Wood as a child; Natalie Wood as an adult), who can melt even Ethan’s hardest of hearts.

Shortly after Ethan’s arrival, the family’s cattle are stolen, so Ethan and Marty join the Texas Rangers in a mission to take back their livestock. When they find the cattle slaughtered, they realize it’s a trap to lure them out into the wilderness and leave the family defenseless back home. Tragically, Ethan and Marty return to the Edwards ranch to find their family massacred by Comanches, led by the ruthless Chief Scar (Henry Brandon).

The only survivors appear to be the young girls, Lucy and Debbie, but they have been abducted by the tribe. Vowing revenge, Ethan and Marty round up a group of cowboys and set off on a quest to find them, through arduous terrain and the turning of the seasons. They are The Searchers.

Screenplay

You’ve seen this plot a thousand times — cowboy searches for loved ones kidnapped by Indians. This deceptively routine story is likely why the film went unmentioned at the Academy Awards, when in fact, the script had outsmarted even the experts.

Screenwriter Frank Nugent shows an uncanny ability to take classic western elements — sweeping landscapes, roaming cowboys, Indian shootouts — and use them to explore new frontiers. Today, the script is heralded as one of the WGA’s Top 101 Screenplays of All Time, placing ahead of classic gems like Ben Hecht’s Notorious (1946) and modern marvels like Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000).

Through Ethan’s character study, the script both denounces the genre’s racism toward Native Americans — explored in films like Broken Arrow (1950) — and gets to the root of the drifter’s complex. Many a western had pictured the archetype of the drifting loner (i.e. Shane), but it was The Searchers that pried into why these men acted this way.

Thus, its greatest achievement is to have us pulling for Ethan to find Debbie, even though we fear what this racist killer might do once he finds her. In essence, Nugent and Ford have hung their entire plot around the fulfillment of one event that may or may not wreck their main character. Rather than a hero sent to save the day, we get an anti-hero sent to see what he will find within himself when the moment of truth arrives. And how much more rewarding that is.

The Duke’s Greatest Role

The duality of Ethan’s character could have proved disastrous for a lesser actor, but John Wayne carries the film on his broad shoulders, joined by rising stars Jeffrey Hunter, Vera Miles and Natalie Wood, along with a spectacular stable of John Ford regulars — Hank Worden, Ward Bond, Ken Curtis and Harry Carey Jr. Ironically, the 48-year-old Wayne was not the first choice for the simple fact that he was 20 years older than Ethan’s character. (A) Thankfully, Ford wound up going with his tried and true Duke, whom he had made a star in Stagecoach (1939) and a superstar in the “Calvary Trilogy” of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950). (A)

If producer Merian C. Cooper thought he had a big star in King Kong (1933), the giant ape was nothing compared to The Duke. Wayne’s sheer popularity allowed Ford to manipulate us so effectively, allowing him to go from comical to sinister at the drop of a cowboy hat, and part of us would still cheer for him. Howard Hawks had tapped into the dark side of Wayne in Red River (1948), and here Ford mines it for all it’s worth.

Even those detractors who would like to paint Wayne into a box of stiff, lanky dullness have to admit The Searchers is a revelation. At one moment, he’s turning a humorous catchphrase — giving pop culture the phrase “That’ll be the day.” The next, he’s showing off some serious acting chops, anguishing over his account of a horrific story: “What do you want me to do, draw you a picture? Spell it out? Don’t ask me. Don’t ever ask me” (See 0:57 into this trailer). It’s his deepest, darkest, and most complex role, voted #87 on Premiere magazine’s 100 Greatest Movie Performances of All Time.

Such distinctions are superfluous compared to the fact that Wayne himself named his son Ethan in honor of the movie. When he finally won the Oscar as Rooster Cogburn in True Grit (1969), it was really the Academy honoring his entire body of his work, of which The Searchers dominates. And when Wayne died shortly after his final public appearance to present Best Picture at the 1979 Academy Awards, it was a picturesque exit, like the door closing him out into the wilderness in the final shot of The Searchers.

Love Affair in Mise-en-Scene

The success off Wayne’s performance is no doubt largely a credit to Ford, whose directorial vision here rivals any I’ve seen. If you want to learn how to direct, you don’t need to go to film school or read some fancy book. Just watch the first 20 minutes of this film. I surely am not the only one whose love affair with film theory began with Ford’s brilliant depiction of a hidden love affair between Ethan and Martha.

The subtext whizzed over my head the first time I saw it as a naive 20-year-old. But as longtime University of Maryland film professor Joseph Miller went back through it step by step, I was floored. There was more to cinema. How stupid I was. My life was changed.

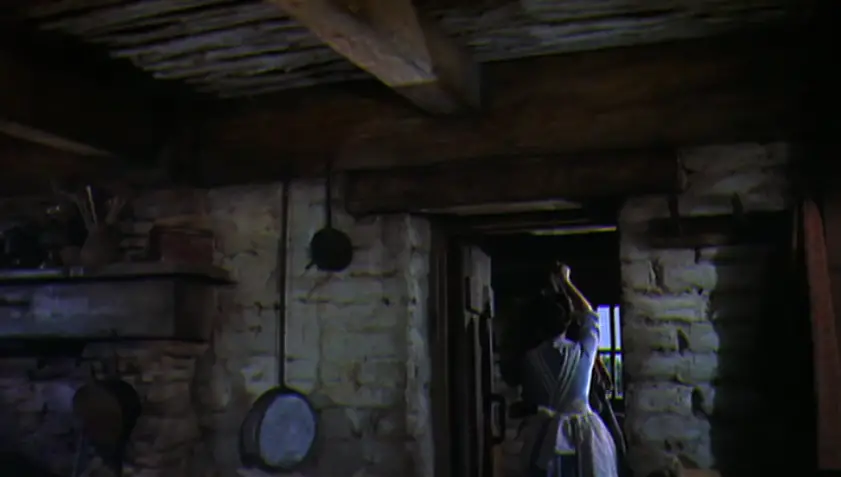

The first hint of the affair comes with the look on Martha’s face as Ethan rides up and kisses her on the forehead. At that moment, the music comes to a brief pause, signifying something major has happened. Watch the way she leads Ethan into the house, backpedaling so as never to break eye-contact with him.

Once inside, Ford puts on a clinic of mise-en-scene — a fancy French term for the meaningful positioning of all elements in the frame. It’s no coincidence that Martha is placed on the same side of the room as Ethan, while her husband, Aaron (Walter Coy), stands on the opposite side of the dinner table.

When Martha helps Ethan off with his coat and brings it into the bedroom, the camera follows her in a pan right, as if representing Ethan’s eyes. His gaze is proven by Ford’s cut back to Ethan, showing his eyes fixated in the direction of Martha.

Next, at the dinner table, we again see Ethan positioned next to Martha. As shown in Stagecoach (1939), Ford loved using positioning at dinner tables to infer meaning.

Next, at the dinner table, we again see Ethan positioned next to Martha. As shown in Stagecoach (1939), Ford loved using positioning at dinner tables to infer meaning.

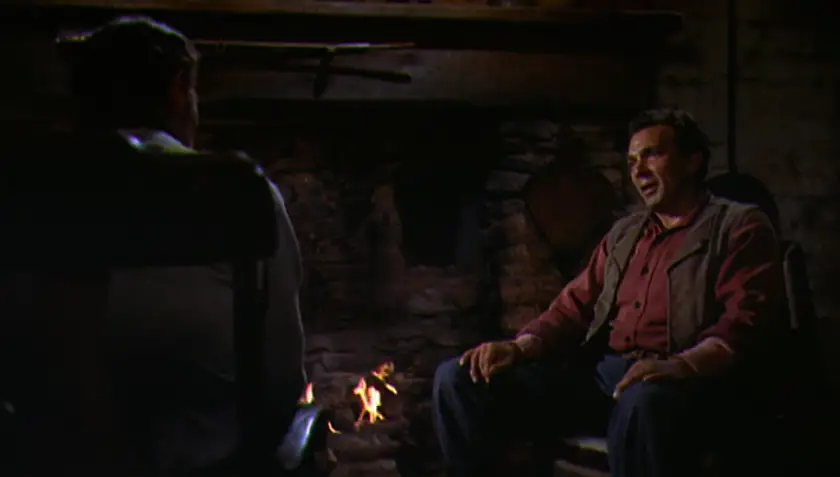

Later, once the children have gone off to bed, we see Ethan, Martha and Aaron talking around the fireplace. Aaron tells Ethan, “You wanted to clear out. You stayed beyond any real reason. Why?” The line is a hint that before the war, Ethan stuck around the ranch just to be near Martha. Note how Ford shows Ethan and Martha together in the same shot here, while Martha is absent from Aaron’s shot.

Later, once the children have gone off to bed, we see Ethan, Martha and Aaron talking around the fireplace. Aaron tells Ethan, “You wanted to clear out. You stayed beyond any real reason. Why?” The line is a hint that before the war, Ethan stuck around the ranch just to be near Martha. Note how Ford shows Ethan and Martha together in the same shot here, while Martha is absent from Aaron’s shot.

When Ethan rises up out of his rocking chair to challenge his brother, notice that he is now standing next to Martha, with Aaron on the other side the room, separated by a burning fireplace in the middle of the frame. The mise-en-scene — Ethan and Martha on one side of the fire; Aaron on the other — reeks of sexual tension. Finally, as Aaron looks down, Martha crosses the fire, becoming engulfed in that tension. She reaches for a burning lantern at the same time as Ethan, and their hands touch, both holding a burning lantern, showing their love still burns for one another.

When Ethan rises up out of his rocking chair to challenge his brother, notice that he is now standing next to Martha, with Aaron on the other side the room, separated by a burning fireplace in the middle of the frame. The mise-en-scene — Ethan and Martha on one side of the fire; Aaron on the other — reeks of sexual tension. Finally, as Aaron looks down, Martha crosses the fire, becoming engulfed in that tension. She reaches for a burning lantern at the same time as Ethan, and their hands touch, both holding a burning lantern, showing their love still burns for one another.

Lover’s Revenge

Understanding the Ethan/Martha affair makes the rest of the film all the more rewarding. It allows us to fully appreciate the scene where Ethan says goodbye to Martha for the last time. Staring straight forward from behind his coffee cup, Rev. Clayton (Bond) senses the gentle interaction between Ethan and Martha behind him. It may be the best acting in Bond’s career and is an absolute triumph of Ford’s visual storytelling prowess.

It also adds gravity to the scene where Ethan and Marty discover the burnt ruins of the Edwards ranch. As Ethan frantically searches the remains, he does not call out his brother’s name, but Martha’s. When he finds Martha’s blue dress laying in front of another building, Ford cuts to a shot from inside the building looking out at Ethan, who enters and drops his head in sadness. We know Ethan’s worst nightmare has been realized. He’s enraged by the thought of a Comanche raping Martha, achieving with her the very thing he has long suppressed (sex).

The question becomes this — is Ethan in love with Martha in desire only, or did they actually have an affair? The film never quite says. In a 1974 interview, Wayne said Ford hinted throughout the movie that Ethan had had an affair with his brother’s wife, and was possibly the father of Lucy and Debbie. (A) If true, this would mean Ethan’s vengence stems from the murder of his lover and the abduction of his own children. How’s that for another layer! Whether they actually had an affair or just mentally desired it is irrelevant. The point is that this is what fuels “the search.”

The real beauty of it all is that it’s so subtle that many casual viewers miss it on first go round. Everything involving the relationship between Ethan and Martha is done without dialogue, without specific mention of it. Ford presents it all visually, like a director should, so that we can go back and discover further layers on repeat viewings.

Bricks and Chairs: Ethan’s Domestic Problem

The Ethan/Martha affair speaks volumes to Ethan’s domestic problem. While The Searchers at first appears to glorify the drifting cowboy, a closer look reveals Ford’s true intentions.

From the opening credits, Ford creates a powerful commentary on the drifter’s longing for a domestic lifestyle. Listen to the lyrics of Stan Jones’ title theme, performed by Roy Rogers & The Sons of the Pioneers: “What makes a man to wander? What makes a man to roam? What makes a man leave bed and board and turn his back on home?” The answer: when that man’s true love has been stolen by his brother. Thus, Ethan becomes one of the most fascinating character studies in the history of movies. If our sympathies are really with Marty, who chooses a life of domesticity with Laurie Jorgensen (Vera Miles), what does this say of the drifter? For all of his great western adventures, perhaps Ford is saying that sometimes “the search” is not all that it’s cracked up to be.

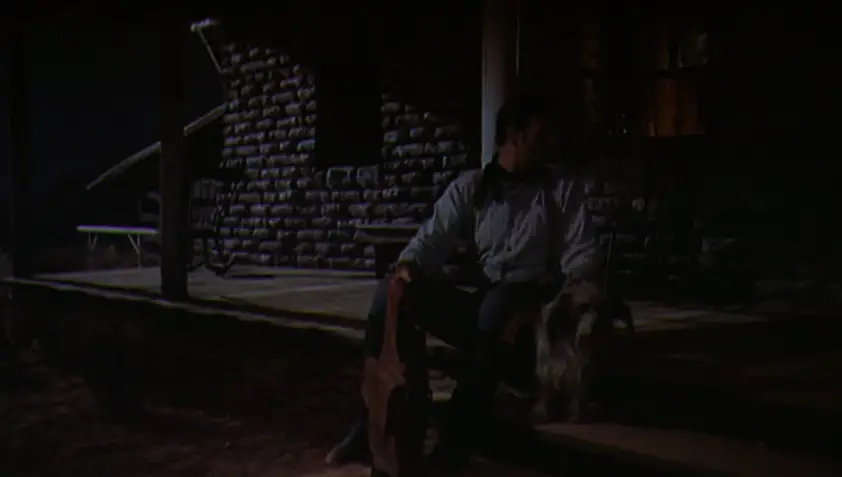

The “brick wall” backdrop of the opening credits symbolizes how Ethan has no entry into the domestic world. In true tragic form, we realize Martha probably settled for Aaron because he was the safer choice. Ethan’s own adventurous nature — his drifter’s complex — cost him his true love.

The brick imagery returns in the scene where Ethan watches Martha head to bed. As Ethan sits on the outside porch, we see Ethan’s POV look longingly as Aaron enters the bedroom with Martha. Ethan wishes he were the one in the bedroom with Martha, but he instead must watch through two door frames (the front door and the bedroom door) that symbolize his real distance from his object of desire.

Note in the above shot that a chair sits between Ethan and Martha’s bedroom. It’s easy to miss the symbolism of this simple piece of furniture, but remember — this is a John Ford movie! The master is at work. And a chair is never just a chair.

When Ethan first arrives, he gets a taste of the domestic lifestyle, embracing his family and giving gifts to the children (who may actually be his children). Fittingly, he sits in the rocking chair, a symbol of homestead stability. It’s only when his brother presses him on domesticity questions that Ethan rises up out of the chair.

The rocking chair goes on to become a sort of motif, mostly tied to the half-crazy Mose Harper (Hank Worden), who’s based on legendary Indian fighter Mad Mose. (A) As Mose sits in the chair and Ethan asks him for information about Scar’s whereabouts, Mose sticks his tongue out at him and says, “Won’t tell ya,” then turns to Marty and says, “[I’ll] tell Marty.” Here, Mose and his rocking chair have become the moral compass for Ethan’s domesticity problem. Even this loon can recognize right (Marty) from wrong (Ethan).

Thus there’s almost a humorous significance to Mose’s constant cries of, “My rocking chair! I want my rocking chair!” The rocking chair is a symbol of domestic moral stability, swaying back and forth, but in the end, holding its ground. It’s a visual idea that was perhaps growing in Ford since Henry Fonda memorably rocked in that chair in My Darling Clementine (1946). How fitting that Mose sit in such a chair at the end of The Searchers donning a top hat, yet another symbol of the civilized world.

Thus there’s almost a humorous significance to Mose’s constant cries of, “My rocking chair! I want my rocking chair!” The rocking chair is a symbol of domestic moral stability, swaying back and forth, but in the end, holding its ground. It’s a visual idea that was perhaps growing in Ford since Henry Fonda memorably rocked in that chair in My Darling Clementine (1946). How fitting that Mose sit in such a chair at the end of The Searchers donning a top hat, yet another symbol of the civilized world.

Unlike Ethan, Marty comes to value the domestic, ultimately choosing to be with Laurie. Ford expresses this through mise-en-scene, both during the wedding scene, where Marty and Laurie stand on the same side of the frame, as well as the final shot, where Marty and Laurie enter the ranch hand-in-hand, leaving Ethan alone against the landscape.

Unlike Ethan, Marty comes to value the domestic, ultimately choosing to be with Laurie. Ford expresses this through mise-en-scene, both during the wedding scene, where Marty and Laurie stand on the same side of the frame, as well as the final shot, where Marty and Laurie enter the ranch hand-in-hand, leaving Ethan alone against the landscape.

Lasting Scars: Ethan’s Racist Problem

The drifter theme is beautifully interwoven with Ford’s chief theme — race — in a scene where Ethan shoots the eyeballs out of an already-dead Native American. When Rev. Clayton asks, “What good did that do you?”, Ethan responds, “By what you preach, none. But what that Comanche believes, ain’t got no eyes, can’t enter the spirit land; has to wander forever between the winds.”

“Wandering between the winds” perfectly articulates the drifter theme. But within this same snippet of dialogue, Ethan’s next words are key. As he saddles up to leave, he turns to the interracial Marty and uses the Native American slur: “Come on, blankethead.” Little does Ethan know, the joke’s on him. It’s he who in the film’s final image will be left alone in Monument Valley to wander forever between the winds. Thus the irony when Ethan visits Scar’s teepee and insists he “won’t stand out here talking in the wind.”

As with Ford’s domesticity theme, his racial theme is at play from the very start of the film. While Roy Rogers sings about Ethan’s drifter problem, the melody behind the lyrics is “Lorena,” a favorite tune of Confederate soldiers. (A) When the credits end and that song gives way to Max Steiner’s beautiful violins, you might also realize the music is actually a slower version of “Bonnie Blue Flag,” one of the biggest anthems of the Confederacy, second only to “Dixie.” (A) Could these song selections be any more indicative of the themes to come?

With such confederate references, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that the film is racist, just as it’s easy to knock Ford for casting a blue-eyed German in the role of Scar and depicting his tribe of Comanches as savages who rape and kill white Texans.

The most troubling scene in this regard comes when Ethan and Marty come across two white girls who have been captured by Scar’s tribe and now act like crazies. A man says, “It’s hard to believe they’re white,” to which Ethan says, “They ain’t white…anymore. They’re Comanche.” But as Ford’s camera pushes in on Ethan’s face of hate, it appears Ford is condemning Ethan for his hatred. This is a far cry from the “hero shot” push-in of Wayne in Stagecoach. This one is judging him.

To call The Searchers a racist film is a blanket statement that’s just as ignorant as the word “blankethead.” The entire film is Ford’s own personal exploration into the subject of race, questioning who exactly was the aggressor in the Cowboy-Indian race war. As Scorsese says, “I think the conflict of America is there in [Ethan’s] face and in his soul in that picture.” (C)

“Yeah, but Scar is the film’s antagonist,” you might say. Yes, but keep in mind that Scar merely represents the Native American version of Ethan. Both are radical representations of their own hatred for the other race. As film scholar Ed Lowry writes, “Never do we see the Indians commit atrocities more appalling than those perpetrated by the white man. Not only does [Ethan] Edwards perform the only scalping shown in the film, but Ford presents the bloody aftermath of a massacre of Indian women and children carried out by the same clean-cut cavalrymen he depicted so lovingly in films like Fort Apache.” (B)

In other words, the Redskins and Whiteskins are given equal footing in the brutality. This is the purpose of the scene when Ethan meets with Scar and says, “You speak pretty good American for a Comanche. Someone teach ya?” Moments later, Scar stands toe-to-toe with Ethan and retorts, “You speak good Comanche. Someone teach you?”

Note the two men stand eye to eye in the teepee. They are immoral equals, with moral Marty pushed off into the background. How are Scar and Ethan equal? Both blame the other race for family deaths and will kill for revenge. In an earlier scene, where Debbie hides behind a gravestone, the marker reads: “Here lies Mary Jane Edwards, killed by Commanches May 12, 1852. A good wife and mother in her 41st year.” This is the source of Ethan’s Native American hatred: his own mother was murdered by Comanches. (A)

Similar motivations also drive Scar, who reveals in the teepee that he has: “Two sons killed by white men. For each son, I take many.” Immediately, Ford zooms/tilts to focus on a medal Scar is wearing around his neck. It just so happens to be the same medal Ethan gave to Debbie earlier in the film.

Similar motivations also drive Scar, who reveals in the teepee that he has: “Two sons killed by white men. For each son, I take many.” Immediately, Ford zooms/tilts to focus on a medal Scar is wearing around his neck. It just so happens to be the same medal Ethan gave to Debbie earlier in the film.

The medal serves multiple purposes. On the surface plot level, it’s a sign that Scar truly is holding Debbie captive. On the level of backstory, it provides a clue to Ethan’s absense after the Civil War. As a French medal awarded to mercenary soldiers who fought between 1865 and 1867 for the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, it implies Ethan served in the French Mexican Expedition. (A) Deeper yet, it drives home Ethan’s domesticity problem. At the start of the film, he gives this medal to Debbie (a token from his wild adventures), and for a brief moment, we see a glimpse of a domestic Uncle Ethan. This is his true responsibility, his imperative, but the murder of Martha and his own wild impulses get in the way. For him to see that medal around the neck of Scar brings those emotions right to the surface. He blames the Indians for robbing him of his last chance at domesticity, and turns to his drifter/searcher impulses to cope.

One of Ford’s most effectively subtle expressions of Ethan’s racist transformation comes in the wardrobe department. Note how he gradually transitions from wearing Confederate reds and grays to Union blues throughout the course of the movie.

Of course, not all clues to the moral structure of the film are this subtle. Ethan’s racial healing is expressed more overtly through dialogue. When he first sees Marty, he says, “Well I could mistake you for a half-breed.” This is followed by the aforementioned “blankethead” comment. By the time he mocks Marty for accidentally taking an Indian bride, we’ve come to expect this type of bigotry from him. But while Ethan laughs his head off about the idea of interracial marriage, the last laugh is on him.

The culmination of Ethan’s internal dilemma comes during the climax, a moment of true suspense when Ethan, eyes wide with rage, has us wondering whether he will actually save his niece or kill her because she’s “gone Injun.” By this point, we have come to doubt Ethan’s true motivation for the title search. Is it really to rescue a family member, or to settle a vendetta of racist hate? Numerous times, he says he would rather kill his niece than have her live “with a buck.” To him, “Living with the Comanche ain’t living.”

What’s more disturbing, it’s not just Ethan who feels this way. According to Laurie, Martha would have been just as upset to see Debbie living with Indians. Perhaps Ethan and Martha were two peas in a racist pod. It’s Laurie who stresses the need for Marty to stand up against Ethan: “Ethan will put a bullet in her brain. I tell you, Martha would want him to.” Such a moment reveals just how much Ford has turned the tables on us as viewers. The protagonist Ethan is borderline villain. Marty and Laurie are our only hope.

At this point, those who still think Ford’s film is racist should check themselves. Ford himself had this to say about America’s history with Native Americans: “It’s a blot on our shield. We’ve robbed, cheated, murdered and massacred them, but they kill one white man and, God, out come the troops.” (D) Meanwhile, Ford has defended his genre’s as basing its treatment on an unfortunate reality. In a 1964 interview with Cosmopolitan magazine, he admitted, “There’s some merit to the charge that the Indian hasn’t been portrayed accurately or fairly in the Western, but again, this charge has been a broad generalization and often unfair. The Indian didn’t welcome the white man… and he wasn’t diplomatic… If he has been treated unfairly by whites in films, that, unfortunately, was often the case in real life. There was much racial prejudice in the West.” (E)

Looking at The Searchers in the context of Ford’s entire career, you could argue that Ford never truly conquered his own racial demons. But at least he tried. As Roger Ebert writes, “In The Searchers I think Ford was trying, imperfectly, even nervously, to depict racism that justified genocide.” To me, this “nervous,” unsure attempt at the issue actually rings more true and more personal than, say, Giant (1956), a fantastic movie released the same year but far more preachy. The title of The Searchers could just as well speak to its director’s own “search” through his own complex feelings on race. And isn’t that what we want most from our filmmakers? To look inward and mend personal demons through artistic expression?

Parallels and Bookends

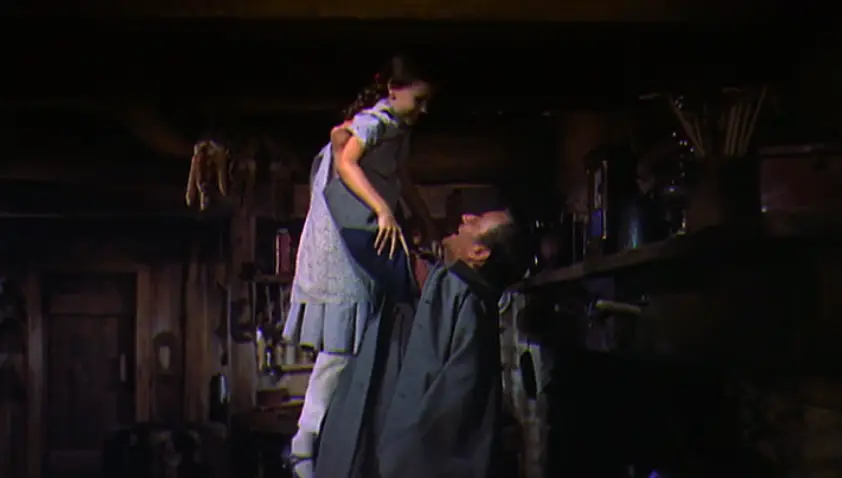

In a weird way, this use of artistic expression to battle person demons exists in the film’s own masterful use of parallelism. After all, it is the familiar image of Ethan lifting Debbie into the air that triggers his mercy during the climax. Not only does this repetition trigger Ethan’s brain from hate to love, it sparks a similar recall in our brains as viewers, and, dare I say, triggers Ford’s own subconscious stand on the issue.

Such thematic control is carried throughout the film, coming full circle between the opening shot of a door opening on Monument Valley, to the final shot of a door closing on a lonely Ethan. The two shots — gorgeously captured by cinematographer Winton Hoch — will forever stand as the greatest bookends in movie history. As film theorist Stefan Sharff said, “Would the meaning of this closing shot have been different if it were not composed through the frame of the doorway … Ford’s repeated use of the door frame as a familiar image imbues it with both dramatic and graphic significance. It introduces symmetry by repetition and creates a vertical contrast (the doorway) to the Vistavision horizontal shape of the frame.” (F)

Pop Culture

Just as those bookends have opened and closed many a movie highlight reel, the film itself has appeared all over our pop culture — in ways you may not even realize.

Of course, there are the aforementioned homages by Spielberg, Lucas and Scorsese, including this uncanny resemblance to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

David Lean watched The Searchers repeatedly while preparing for Lawrence of Arabia (1962) to help him get a sense of how to shoot a landscape. It shows, as Lean’s entrance of Sherif Ali from deep desert background echoes Ethan’s entrance from the deep background of Monument Valley in The Searchers. Lawrence’s raid of Akaaba also rings similar to Ethan’s horseback raid of the Comanche village — rapid side dolly and all.

Sergio Leone called The Searchers one of his favorite films and lovingly referenced it in the spectacular Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Robert Aldrich referenced John Wayne’s matted tunnel shot with Burt Reynolds at the end of The Longest Yard (1974). And Ford’s film was practically remade by Ron Howard as The Missing (2003).

Still, the greatest pop culture impact came in the music industry. The film inspired John McNally to form his British band The Searchers, exactly a year after Ford’s film. You know them from their #3 Billboard hit “Love Potion Number 9.”

Most importantly, the film inspired Buddy Holly’s catchy No. 1 hit “That’ll Be The Day.” Released just a year after Ford’s film, the song was inspired directly by Wayne’s quote in The Searchers — one that has since become common language for any sarcastic dismissal of an idea: “That’ll be the day.”

Legacy

The way the film continues to show up in filmmakers’ work is a testament to its lasting impact. Its thematic strength, mixed with Ford’s artful expression, continues to fascinate, and its place in the listology game continues to rise. In 1997, it ranked as low as #98 on the AFI’s Top 100, but by 2007, it had risen all the way to #12. Meanwhile, the 2002 Sight & Sound critics poll ranked it the #11 greatest film of all time, and the AFI recently named it the single greatest western of all time.

Whether its international or domestic, art or mainstream, everyone respects The Searchers. It commands respect if for no other reason than its complex handling of a tough issue. Spielberg said it “arouses your passions and certainly challenges you to try to like Ethan Edwards, because he’s a racist,” while Jean-Luc Godard lovingly said, “How can I hate John Wayne upholding [Barry] Goldwater and yet love him tenderly when abruptly he takes Natalie Wood into his arms in the last reel of The Searchers?” (B)

When you have mainstream kings like Spielberg and Lucas hailing your film just as much as academic favorites like Godard and Scorsese, you must be doing something right. What makes The Searchers such a masterpiece in my eyes is that on first viewing, you can gawk at the gorgeous landscapes and enjoy a knock-down fist fight that makes you laugh out loud about “somebody’s fiddle.” Then, a dozen viewings later, you can relish a complex exploration of the hero’s secret motivations that makes you both admire and abhor him, while basking in a director with such a rare mastery of his medium. In short, you can enjoy the film on the surface without knowing its secret layers — or, you can enjoy the film on a deeper level knowing them. All films should aspire to this.

Ford was not only a great storyteller, he was an artist. Monument Valley was his canvas and The Searchers his masterpiece. If you want a window into how cinematic art can be disguised as popcorn entertainment, peer through the door of the Edwards ranch. Other directors have been doing it for years.

Citations:

CITE A: IMDB Trivia

CITE B: Turner Classic Movies website: http://www.tcm.com/thismonth/article/?cid=1093&rss=mrqe

CITE C: AFI’s 100 Movies 10th Anniversary Edition

CITE D: IMDB Bio

CITE E: Libby, Bill. ‘The Old Wrangler Rides Again’. John Ford Made Westerns. Eds. Gaylyn Studlar and Matthew Bernstein. Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2001. p. 286. I pulled this from a wikipedia link: http://www.brentonpriestley.com/writing/searchers.htm

CITE F: Stefan Sharff, The Elements of Cinema