Director: Robert Zemeckis

Writer: Winston Groom (book), Eric Roth (screenplay)

Producer: Wendy Finerman, Steve Starkey, Steve Tisch

Photography: Don Burgess

Music: Alan Silvestri

Cast: Tom Hanks, Robin Wright Penn, Sally Field, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, Michael Conner Humphreys, Hanna Hall, Siobhan Fallon, Haley Joel Osment

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Screenplay

- Career Roles

- Magic Legs

- Zemeckis & Welles: Peas & Carrots

- Movement Through Objects

- Transitions

- Mise-en-Scene

- The Soundtrack of Our Lives

- The Politics of Gump

- The Wisdom of Gump

- Pop Culture

- Legacy & Inspiration

“I remember early on in the rehearsals, the two of us having this conversation about what just exactly this movie was going to be,” said Gary Sinise of working with Tom Hanks on Forrest Gump. “There’s this feather, there’s some chocolates, there’s Vietnam, Tom moons President Johnson, there’s Bubba, Momma, Jenny, I lose my legs, he runs a lot, ping pong, a hurricane, shrimp. And the way our great director Bob Zemeckis would describe it, sometimes we thought we were making Citizen Kane and other times we thought Roger Rabbit.” (A)

Is Forrest Gump a profound commentary like Kane, or an effects-driven romp like Roger Rabbit? Such a broad spectrum makes for a most fascinating discussion about the critics and the mainstream. While the public made Gump the highest grossing movie of 1994 and vote it an 8.7 on IMDB today, the experts remain splintered. They simultaneously shower it with Oscars (six including Best Picture) and snub it entirely at Cannes, Venice and Berlin. They vote it into the AFI Top 100, but give it zero votes on the Sight & Sound critics poll. Most of all, they give it mixed reviews with a 72% on rottentomatoes, some echoing Pauline Kael — “I hated it thoroughly” — and others echoing Roger Ebert — “Forrest Gump is not only a great and magical entertainment, but the more you think about it, the more it reveals itself as actually sort of profound.”

As Entertainment Weekly wrote in 2004, “Nearly a decade after it earned gazillions and swept the Oscars, Robert Zemeckis’ ode to 20th-century America still represents one of cinema’s most clearly drawn lines in the sand. One half of folks see it as an artificial piece of pop melodrama, while everyone else raves that it’s sweet as a box of chocolates.” (D) I proudly admit my sweet tooth. Ladies and gents, I present: The Case for Forrest Gump.

Plot Summary

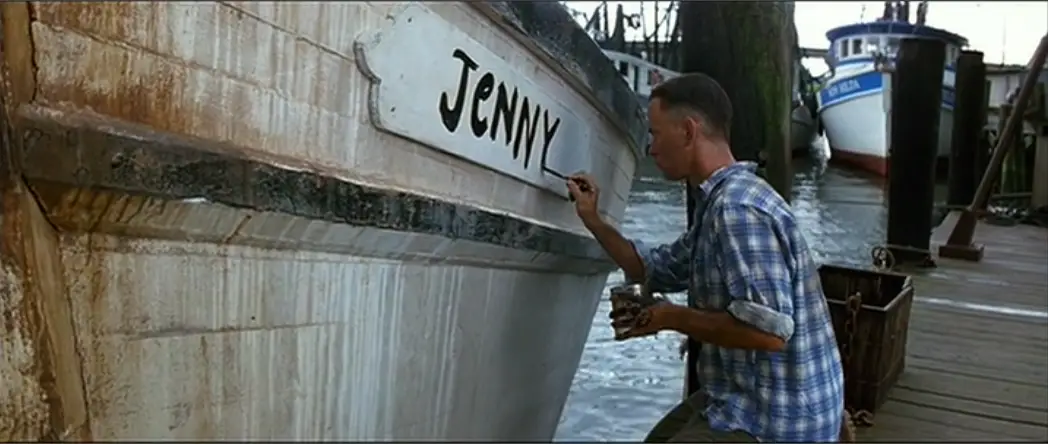

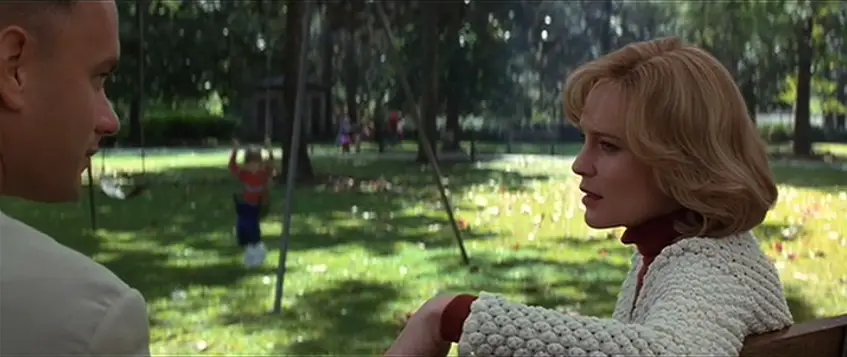

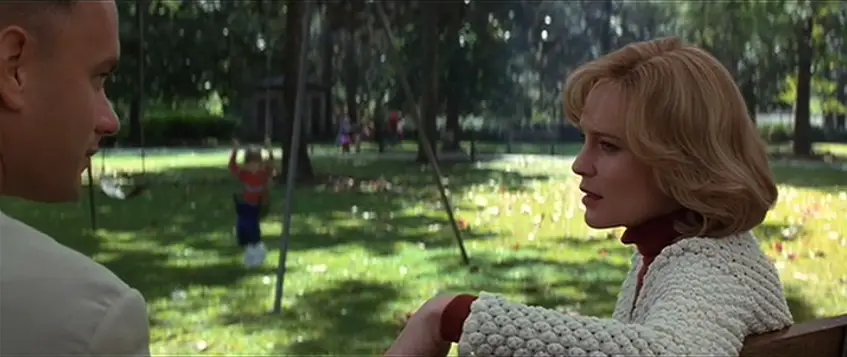

We first meet Alabama simpleton Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks) on a park bench in Savannah, Georgia, where he waits in crisp white suit and high-and-tight haircut to deliver chocolates to his lifelong flame, Jenny Curran (Robin Wright). As various strangers take a seat next to him, waiting for the bus, Forrest is more than willing to tell them (and us) his life story.

He takes us back to the days of his childhood, where Young Forrest (Michael Conner Humphreys) suffers from an IQ of 75 and braces on his legs. These aren’t handicaps, according to his single mother (Sally Field), who tells him he is no different from anybody else: “If God intended us all to be the same, he’d have given us all braces on our legs.”

He takes us back to the days of his childhood, where Young Forrest (Michael Conner Humphreys) suffers from an IQ of 75 and braces on his legs. These aren’t handicaps, according to his single mother (Sally Field), who tells him he is no different from anybody else: “If God intended us all to be the same, he’d have given us all braces on our legs.”

With an estranged husband on permanent “vacation,” Forrest’s Momma raises him in an old farmhouse in Greenbow, Alabama, where visitors are always coming and going. On the bus the first day of school, Forrest befriends Young Jenny (Hanna Hall), the sweet victim of an abusive father, who prays for God to turn her into a bird to fly far, far away. Forrest is her comfort and the two are like “peas and carrots.” It is in Jenny’s presence that he finally breaks out of his leg braces.

With an estranged husband on permanent “vacation,” Forrest’s Momma raises him in an old farmhouse in Greenbow, Alabama, where visitors are always coming and going. On the bus the first day of school, Forrest befriends Young Jenny (Hanna Hall), the sweet victim of an abusive father, who prays for God to turn her into a bird to fly far, far away. Forrest is her comfort and the two are like “peas and carrots.” It is in Jenny’s presence that he finally breaks out of his leg braces.

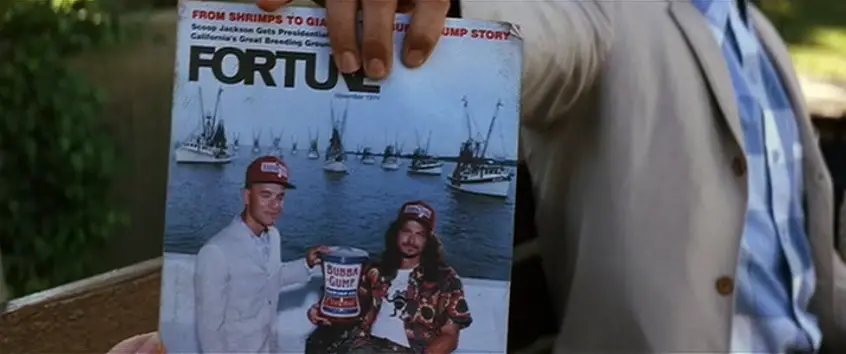

After breaking those chains, Forrest continues to defy the odds. He plays Division 1 football at the University of Alabama; earns the Medal of Honor in Vietnam for saving his fellow troops and commander, Lt. Dan Taylor (Gary Sinise); travels to China on the U.S. ping pong team; appears on national talk shows; meets several U.S. presidents; launches a shrimping company to fulfill the dream of his war buddy Bubba (Mykelti Williamson); and goes for a highly publicized cross-country run.

After breaking those chains, Forrest continues to defy the odds. He plays Division 1 football at the University of Alabama; earns the Medal of Honor in Vietnam for saving his fellow troops and commander, Lt. Dan Taylor (Gary Sinise); travels to China on the U.S. ping pong team; appears on national talk shows; meets several U.S. presidents; launches a shrimping company to fulfill the dream of his war buddy Bubba (Mykelti Williamson); and goes for a highly publicized cross-country run.

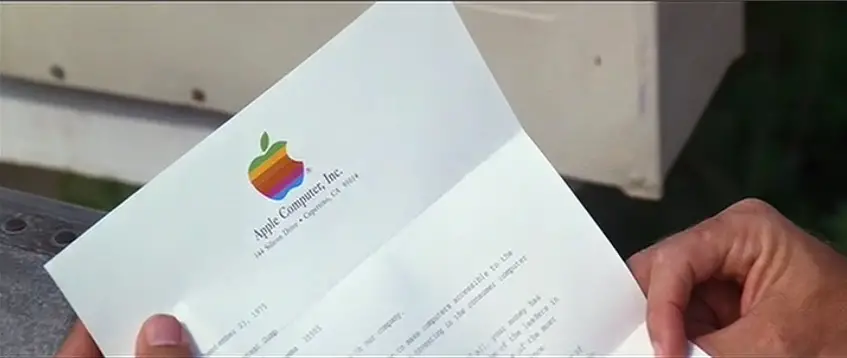

Each step of the way, Forrest happens to be at the crossroads of history, be it calling in the Watergate scandal, or getting in on the ground floor of Apple. Of course, he has no idea he’s changing the world. The “zeitgeist” may be following him, but his sights are set on one thing: his undying love for Jenny.

Each step of the way, Forrest happens to be at the crossroads of history, be it calling in the Watergate scandal, or getting in on the ground floor of Apple. Of course, he has no idea he’s changing the world. The “zeitgeist” may be following him, but his sights are set on one thing: his undying love for Jenny.

Screenplay

Based on the 1986 book of the same name by Winston Groom, the screenplay of Forrest Gump was penned by Eric Roth. While his work may not equal that of Quentin Tarantino, who won Best Original Screenplay for Pulp Fiction (1994), Roth won for Best Adapted Screenplay — an art all its own. Roth took a rather unknown novel and — after the movie’s release — turned it into a bestseller. What’s more, the script landed #89 on the WGA’s Top 101 Screenplays of All Time, succeeding on four main fronts: a fascinating premise, flexible tone, superb parallel action structure and memorable dialogue.

Premise. The film’s story goes in numerous creative directions, but its core premise is not entirely original. It works as a sort of combination between Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979), where Peter Sellers plays an isolated simpleton who is mistaken for a genius when he finally enters the outside world, and Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983), where the title character meets various famous people throughout history. Top it all off with the same charm of Rain Man (1988), and you have Forrest Gump.

Tone. One of the script’s more remarkable achievements is its ability to blend genres with a flexible tone. Roger Ebert wrote, “It’s a comedy, I guess. Or maybe a drama. Or a dream,” describing a special film where laughs, tears and philosophy appear in equal amounts. (F) You could also throw in the action movie, the war film, the buddy picture, the sports flick, the biopic, the romance and the musical collage.

Structure. The script also provides a great example of story structure, particularly the device of parallel action. Forrest and Jenny’s stories play out simultaneously, diverging, converging and diverging again. It’s this element that Roth carried over most for the relationship between Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008). There was even Brad Pitt traveling the seas, looking up at the stars and wondering if Blanchett was looking back at him.

Dialogue. Finally, the script provides a number of quotable pieces of dialogue. Most famous is the line that ranks #40 on the AFI’s 100 Movie Quotes: “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get.” After the film’s release, you couldn’t go anywhere without hearing people say, “Run, Forrest! Run!”, “Stupid is as stupid does” and “That’s all I have to say about that.” I think we’ve actually reached the point where some lines should be retired.

We should instead move on to the more obscure gems, as Roth’s dialogue is so much more than “chocolate.” Some of it works in the form of narration: “You wouldn’t believe me if I told you this, but I could run like the wind blows;” “Scared of what, I don’t know. But I think it was her grandma’s dog;” and “Sometimes I guess there just aren’t enough rocks.”

Other times, they appear on-screen in Forrest’s extended flashback: “They’re sending me to Vietnam. It’s this whole other country;” “Something bit me;” She tastes like cigarettes” (which Roth later explored in The Insider); “I’m glad we are here together in our nation’s capital;” and “Sorry for starting a fight in the middle of your Black Panther Party.”

Other times, they appear on-screen in Forrest’s extended flashback: “They’re sending me to Vietnam. It’s this whole other country;” “Something bit me;” She tastes like cigarettes” (which Roth later explored in The Insider); “I’m glad we are here together in our nation’s capital;” and “Sorry for starting a fight in the middle of your Black Panther Party.”

Still, the best moments come in exchanges between two characters, where Forrest totally misreads what his friends are trying to tell him. There’s this genius exchange in Jenny’s dorm room:

Jenny: You ever been with a girl, Forrest?

Forrest: I sit next to them in my home economics class all the time.

Such misunderstanding makes for comic relief in an otherwise tragic moment in Vietnam:

Bubba: Forrest, why’d this happen?

Forrest: You got shot.

Later, there’s this gem as Jenny tries explain that she has AIDS:

Jenny: Forrest, I’m sick.

Forrest: What, do you have a cough due to cold?

And perhaps my favorite:

Forrest: Lieutenant Dan! What are you doing here?!?

Lt. Dan: I thought I’d try out my sea legs.

Forrest: (pause) But you ain’t got no legs, Lieutenant Dan.

Career Roles

Of course, none of this would have worked if it weren’t for the pitch-perfect casting of Tom Hanks, who turned Forrest into his own career role and Premiere magazine’s #24 Greatest Character of All Time. Hanks shows great range, nailing comedy (“That’s my boat”), heartache (“I’m not a smart man, but I know what love is”), pride (sticking his chin out at the wedding), naive shock (“He’s got a daddy named Forrest, too?”) and loss (“If there’s anything you need, I won’t be far away”).

The film won Hanks his second straight Oscar, having won the previous year for Philadelphia (1993), making him the first to win back-to-back Best Actors since Spencer Tracy with Captains Courageous (1937) and Boys Town (1938). On Oscar night, Hanks joked, “I think if I’m nominated for anything next year, there’ll be a wave of suicide jumpers from the third tier of the Chandler Pavilion.” (C)

Speaking of suicide jumpers, is there a more memorable piece of acting than Robin Wright’s drugged-out suicide contemplation? Wright got her start in TV soap operas, earning three Daytime Emmy noms for Santa Barbara (1984). She soon appeared as Princess Buttercup in The Princess Bride (1987), which led to her casting as Maid Marian in Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1991), until her pregnancy forced her to back out. Finally, she found her career role as Jenny, earning her first and only Golden Globe nomination, before seeing renewed success as Claire Underwood alongside Kevin Spacey on Netflix’s “House of Cards.”

Speaking of suicide jumpers, is there a more memorable piece of acting than Robin Wright’s drugged-out suicide contemplation? Wright got her start in TV soap operas, earning three Daytime Emmy noms for Santa Barbara (1984). She soon appeared as Princess Buttercup in The Princess Bride (1987), which led to her casting as Maid Marian in Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1991), until her pregnancy forced her to back out. Finally, she found her career role as Jenny, earning her first and only Golden Globe nomination, before seeing renewed success as Claire Underwood alongside Kevin Spacey on Netflix’s “House of Cards.”

By 1994, Sally Field had long been America’s sweetheart. She had won an Oscar for standing on a table with a “UNION” sign in Norma Rae (1979); proclaimed “You like me!” after winning another for Places in the Heart (1984); melted hearts in Steel Magnolias (1989) and dominated the box office in Mrs. Doubtfire (1993). Still, many will remember her as Mrs. Gump, the rock we keep coming back to as the mother who “always had a way of explaining things so we could understand them.”

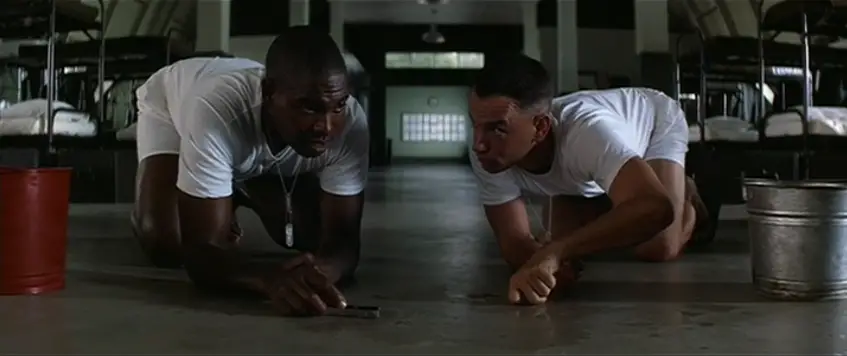

Mykelti Williamson is an equally crucial piece of the film’s success. It’s no coincidence that his shrimp rants became the talk of the town. The role led to his casting in a number of popular films, from Heat (1995) to Con-Air (1997) to Lucky Number Slevin (2006), and spawned the real-life Bubba Gump Shrimp restaurant chain.

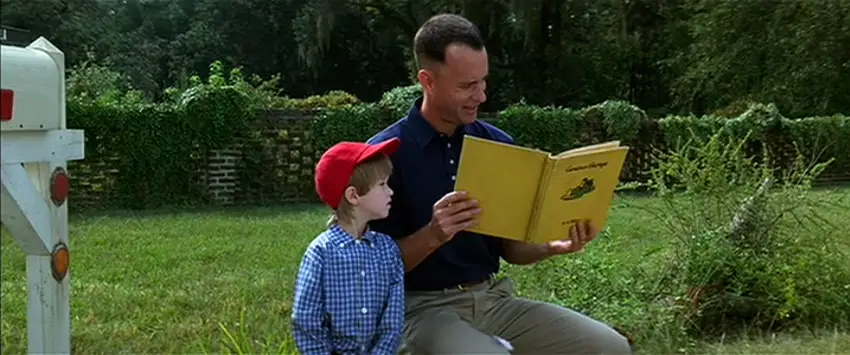

The child actors in the film are also fantastic. Michael Conner Humphreys was cast as Young Forrest because of his unique real-life accent. As Young Jenny, Hannah Hall is the epitome of sweet innocence being robbed of its innocence before our very eyes. Finally, at the end of the film, we get the debut of Haley Joel Osment as Forrest Junior, shortly before his Oscar-nominated turn in The Sixth Sense (1999). “When I was 4, I got this script called Forrest Gump, which I couldn’t read,” said Osment at Tom Hanks’ AFI Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony. “… Many years have gone by since the shooting of Forrest Gump, but no matter how many years go by, Tom, Forrest Gump is a film that will never be forgotten. And what an honor to be forever captured in time as your son.”

Last but not least is Gary Sinise, who earned his first and only Oscar nomination, losing to Martin Landau’s powerhouse performance in Ed Wood (1994). The honor was deserved. Sinise is charming as the Vietnam War officer, absolutely believable in his wheelchair-bound post-war state (spoofing Dustin Hoffman’s “I’m walking here!”), captivating in his taunting of God from a ship mast (“You call this a storm?!?”) and inspiring in his ultimate redemption (“I never thanked you for saving my life”). Humorously, Sinise and Hanks reference their next project together, Apollo 13 (1995), as Sinise taps his titanium alloy leg and says, “Same stuff they use on the space shuttle” — ironic because Forrest pulls people away from the moon landing broadcast by his amazing ping pong skills.

Magic Legs

The legless Lt. Dan was made possible in part by Sinise’s performance, and the rest by special effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). Zemeckis was always an advocate for groundbreaking effects, from DeLoreans disappearing in streaks of fire in Back to the Future (1985) to live-action actors mixing seamlessly with cartoons in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). Forrest Gump would officially cement his reputation for pushing the visual envelope, winning the Oscar for Best Visual Effects.

The fast-moving action of ping pong balls, flying war choppers and the famous floating feather were all done digitally. Still, the greatest achievement is the integration of Tom Hanks in archival footage, from riding in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) to inspiring the lyrics to “Imagine” in a Dick Cavett interview with John Lennon.

Two scenes even had to be cut, including Forrest coming across a Marther Luther King Civil Rights march, and Forrest hitting George H.W. Bush in the crotch with a ping pong ball.

Zemeckis & Welles: Peas & Carrots

Which brings us back to the original question — is Forrest Gump more like Citizen Kane or Roger Rabbit? After all, Gump‘s editor Arthur Schmidt won his second Oscar after collaborating with Zemeckis on Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). At first, the mere thought of comparing Zemeckis to Welles seems ridiculous, and almost an insult to film history considering Zemeckis won Best Director in ’94, while Welles lost in ’41. Like the famous political line, “Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy,” most academics would say, “Robert, you’re no Orson Welles.”

And yet, when assessing any film’s directorial merits, it’s helpful to compare them to history’s ultimate example of directorial vision — Citizen Kane. So, I sat down and forced myself to compare the two, and the further I got, the more the leg braces of skepticism magically buckled and my mind was off and “run-ning.” While Welles’ directorial work is clearly superior, I was pleasantly surprised by Zemeckis’ directorial prowess. I went from thinking he and Welles were complete “apples and oranges,” to realizing they were more like “peas and carrots” than I ever imagined.

First and foremost, both effectively place contemporary actors into archival footage of historical figures. Long before Tom Hanks shared the screen with John F. Kennedy, Welles appeared next to Teddy Roosevelt in Citizen Kane. Of course, Welles gets far more credit for this, because he did it 53 years earlier, without the benefit of CGI.

In a way, Welles and Zemeckis share the same Roger Rabbit childlike spirit, calling the camera the world’s “most expensive paintbox.” You can see the “magic” in their creative approaches to visual effects, and I’m not talking just creativity in the design of the effects themselves. I mean going the extra mile — spacially — daring fellow filmmakers to wonder how they achieved certain things.

Movement Through Objects

While Welles had his camera literally move through objects in Kane (tables, signs), Zemeckis has his actors’ limbs move through digital objects. For example, it’s clear that Sinise’s legs aren’t tucked under. So, filmmakers would know that his legs must be extended with special blue socks deleted by CGI. Yet several times, Sinise’s deleted socks actually swing through objects! At one point, they swing through a table, which was added later digitally. It’s all about going the extra mile.

At another point, Sinise’s CGI socks swing through the side of a ship.

At another point, Sinise’s CGI socks swing through the side of a ship.

Transitions

Also like Kane, Zemeckis takes great care to deliver seamless transitions between scenes. While Welles cleverly cuts from Leland’s campaign stump to Kane’s political rally, Zemeckis cuts back and forth between Forrest and Jenny’s lives.

The first example comes on New Year’s Eve. As Jenny leaves the room of a one-night stand, the camera pans and holds on a TV set showing the Times Square ball dropping. We then cut to Forrest and Lt. Dan watching the same ball drop in a New York City bar.

Zemeckis does it again — and most seamlessly — after Jenny’s near suicide leap. As she gathers herself and looks up at the moon, we cut to a shot of the moon, thinking it’s Jenny’s POV. Then, as the camera tilts down, we reveal it’s actually Forrest looking up at the same moon while laying in his shrimp-boat hammock.

Zemeckis does it again — and most seamlessly — after Jenny’s near suicide leap. As she gathers herself and looks up at the moon, we cut to a shot of the moon, thinking it’s Jenny’s POV. Then, as the camera tilts down, we reveal it’s actually Forrest looking up at the same moon while laying in his shrimp-boat hammock.

A final example comes as Forrest and Jenny watch Fourth of July fireworks together by an Alabama lake. Zemeckis dissolves from the live fireworks in the sky, to a TV broadcast of fireworks above the Statue of Liberty. Such transitions are not just amusing displays of craftsmanship. They symbolically show how we’re all interconnected.

Mise-en-Scene

Zemeckis also strives for symbolic mise-en-scene. During the scene at the Watergate Hotel, you’ll notice a signed photo of Marilyn Monroe behind a photo of the Kennedy brothers. Monroe was rumored to have had affairs with both Kennedys, putting a “morning after” toothbrush dent in their squeaky clean “soap bar” image. Pointing out this type of hidden political scandal works perfectly for a scene where Forrest exposes the corruption of the Nixon administration at Watergate.

Later, when Jenny tells Forrest that she’s “sick,” presumably with AIDS, Zemeckis shows Little Forrest swinging in the background between them. Is this a hint that Forrest may have contracted AIDS from Jenny, as well? What type of life lies ahead for Tom Hanks after the credits roll? Is it that of Philadelphia? Sneaky stuff, Zemeckis. Very sneaky.

Still, the best use of mise-en-scene comes during the adult “run Forrest run” scene. As he sprints away from a truck, note the “stars and bars” of a Confederate license plate. Here, Zemeckis equates the “stars and bars” with the villains of this scene, turning Forrest into a symbol of America itself — running away from a racist past. When Forrest says he could “run like the wind blows,” I can’t help but think of the old southern, slave-owning life being “gone with the wind.” As the country band Alabama put it: “Song, song of the south. Sweet potato pie and I shut my mouth. Gone, gone with the wind. Ain’t no body lookin’ back again.” Run, Forrest, run indeed.

The Soundtrack of Our Lives

Perhaps Zemeckis’ greatest touch is his choice of music. To compose the score, he brought back his favorite collaborator Alan Silvestri (Back to the Future, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?). The Oscar-nominated “Forrest Gump Suite” (below) has five distinct parts — the piano feather theme (0:00-2:15), the violins of love and loss (2:16-3:58), the playful childhood piano echoing Elmer Bernstein’s To Kill a Mockingbird (3:58-4:55), the hallowed choir theme (4:55-6:27) and the upbeat theme of triumph (6:27).

Not only did he tap the right man for the musical score, he also compiled one of the greatest soundtracks in movie history. The two-disc Forrest Gump Special Edition Soundtrack entered the Billboard Top 10 Albums and might be the greatest compilation of American music ever laid to celluloid. Each song takes older generations back to that time, while younger generations immediately associate each with Gump.

We get Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog,” Duane Eddy’s “Rebel Rouser,” Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” CCR’s “Fortunate Son,” Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” The Mamas and the Papas’ “California Dreamin’,” The Doors’ “Break on Through,” Canned Heat’s “Let’s Work Together,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson,” Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers,” The Youngbloods’ “Let’s Get Together,” Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco,” The Byrds’ “Turn Turn Turn,” KC & The Sunshine Band’s “Get Down Tonight,” Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” and “Sweet Home Alabama,” Jackson Browne’s “Running on Empty” and Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind,” just to name a few.

The Politics of Gump

You might say Gump is the “We Didn’t Start the Fire” of movies. For anyone born after, say, 1980, the film serves as a visual textbook of American history, covering the birth of rock ‘n roll, the Civil Rights Movement, the hippie movement, Vietnam, the moon landing, Watergate, disco, the Reagan ’80s and beyond. We experience Elvis, Bear Bryant, Alabama school integration, the Black Panthers, multiple assassination attempts, JFK, LBJ, John Lennon, protests, napalm, drug culture and disabled vets. Zemeckis himself described it as “Norman Rockwell painting the baby boomers.” (C) This is why the film is occasionally aired on the History Channel, and why in 2011, the Library of Congress selected Gump for its National Film Registry to preserve as “cultural treasures.”

And yet, for all the history, the film’s detractors take issue with how the events are covered. British critic David Thomson was the most harsh, calling Gump “one of those travesties that set back the American movie at a stroke.” (G) Such critiques explain the film’s less than stellar 73% on rottentomatoes. Time to debunk the criticisms.

Apathy? Some critics hate the fact that so much history is brushed over so quickly, promoting ignorance and apathy over activist engagement. While I agree that too many moviegoers are sadly apathetic to world affairs, it is far too simplistic to paint Forrest as a passive man of ignorance. A number of historical things may happen to him, but it’s because he goes out and happens to things. While Forrest ultimately returns to his hometown later in life, he also ventures off and takes chances, plays college football, meets national leaders, travels to foreign countries, dominates the international stage, starts a shrimping business, and goes on a spontaneous cross-country run.

Political Bias? Other progressive critics knock the film as a champion of purely conservative views, but to claim this ignores the duality of Forrest’s life experience. His soulmate is a hippie played by the ex-wife of the ultra-liberal Sean Penn (Robin Wright), while his best friend is a multi-generational military officer, played by a once potential Republican candidate (Gary Sinise). For each moment of conservatism — dancing in Nikes to “Sweet Home Alabama,” where “a southern man don’t need [Neal Young] around anyhow” — there is also a moment of liberalism — baring his ass to President Johnson and teaching Elvis how to shake his hips. It’s funny how what was once radically liberal (’50s rock ‘n roll) now makes for conservative nostalgia (ahh, the good old ’50s).

Political Bias? Other progressive critics knock the film as a champion of purely conservative views, but to claim this ignores the duality of Forrest’s life experience. His soulmate is a hippie played by the ex-wife of the ultra-liberal Sean Penn (Robin Wright), while his best friend is a multi-generational military officer, played by a once potential Republican candidate (Gary Sinise). For each moment of conservatism — dancing in Nikes to “Sweet Home Alabama,” where “a southern man don’t need [Neal Young] around anyhow” — there is also a moment of liberalism — baring his ass to President Johnson and teaching Elvis how to shake his hips. It’s funny how what was once radically liberal (’50s rock ‘n roll) now makes for conservative nostalgia (ahh, the good old ’50s).

Issue by issue, Forrest Gump presents the duality of the political spectrum:

Sex. Forrest is a stand-up college athlete, but his academic life begins by his mother banging the elementary school principal. He is taken aback by his first sight of breasts, but ejaculates in the bathrobe of Jenny’s college roommate. He doesn’t like girls who taste like cigarettes, but births a child out of wedlock.

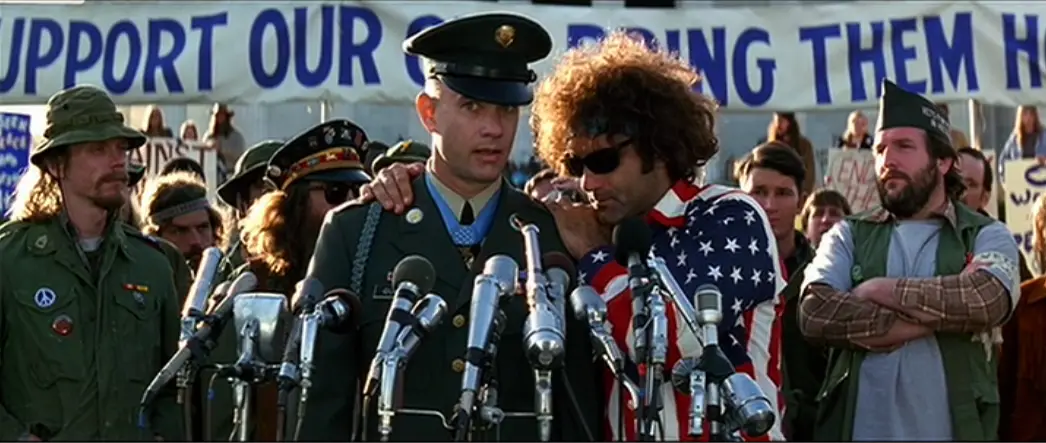

War. Lt. Dan goes from a war hawk battling the Vietcong to marrying a Korean woman named Susan. Forrest heeds the call to serve his country, then delivers what appears to be an anti-war speech thwarted by a corrupt military official.

War. Lt. Dan goes from a war hawk battling the Vietcong to marrying a Korean woman named Susan. Forrest heeds the call to serve his country, then delivers what appears to be an anti-war speech thwarted by a corrupt military official.

Race. Forrest is named after the founder of the Klu Klux Klan, but when a schoolmate uses the racial slur “coon,” Forrest leaves the crowd to help desegregate America’s first school. He gets kicked out of a Black Panther Party, then donates money to Bubba’s bayou family so that “his mama didn’t have to work in nobody’s kitchen no more.” All the while, it is Forrest who struggles to find seats on the bus, ultimately sitting with a black man, who becomes his “best good friend” and Rosa Parks savior.

Religion. While Forrest sings in a church choir and speaks of Lt. Dan making peace with God, he ultimately imagines Jenny as a reincarnated bird.

No matter what issue you want to throw out, liberals and conservatives can both find themselves in Gump. That’s because Forrest does not live by liberal or conservative principles — he only does things because they are right. He is the guiding light of purple, the mixing of red states and blue states, a cross-section of America. As Peter Chomo writes, he’s a “social mediator and an agent of redemption in divided times.” (E)

No matter what issue you want to throw out, liberals and conservatives can both find themselves in Gump. That’s because Forrest does not live by liberal or conservative principles — he only does things because they are right. He is the guiding light of purple, the mixing of red states and blue states, a cross-section of America. As Peter Chomo writes, he’s a “social mediator and an agent of redemption in divided times.” (E)

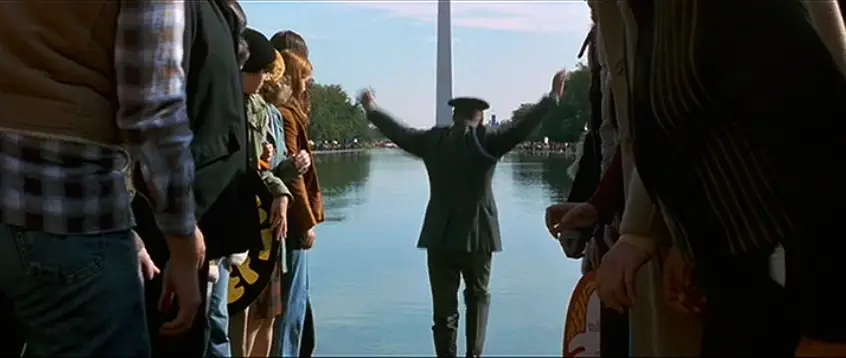

Is there a movie that better captures this site’s mission? Zemeckis understands that open minds and respectful temperaments can go a long way, in our movie discourse and beyond. So when the Vietnam-vet Forrest parts a crowd to embrace the hippie Jenny in the middle of the National Reflecting Pool, it’s a coming together of all political stripes and a celebration of all that is good in America.

Newsday‘s Jack Matthews wrote that Forrest adds “perspective to the two most disruptive decades in modern history,” with his character serving “as a counterpart to the anger and confusion of America’s social revolution, a sort of benign moral compass in the midst of the storm.” (B)

“That’s what the movie is about. It’s trying to describe American history and our reaction to it,” Gene Siskel said. “There’s a beautiful sequence toward the end of the picture where he’s running through the American landscape and his mother talks about letting things go and moving on from them, and I had a feeling that, really, what the film was about for me, is that for all the media attention, all of our knowledge about recent events, we have still not adequately mourned the troubles that we’ve had as a nation. We still have not come to terms with JFK’s assassination, with Vietnam, and so this movie lets us, through this sweet soul, reminds us of this time.”

“That’s what the movie is about. It’s trying to describe American history and our reaction to it,” Gene Siskel said. “There’s a beautiful sequence toward the end of the picture where he’s running through the American landscape and his mother talks about letting things go and moving on from them, and I had a feeling that, really, what the film was about for me, is that for all the media attention, all of our knowledge about recent events, we have still not adequately mourned the troubles that we’ve had as a nation. We still have not come to terms with JFK’s assassination, with Vietnam, and so this movie lets us, through this sweet soul, reminds us of this time.”

Roger Ebert agreed with this assessment: “Later on thinking it over, I realized that in a way Forrest and Jenny represent the American population in the last 40 years, stumbling from one historical event to another, swept along by circumstances, sometimes rising to great heroic action, sometimes falling by the wayside. … Forrest Gump is not only a great and magical entertainment, but the more you think about it, the more it reveals itself as actually sort of profound.”

The Wisdom of Gump

For all this, I believe folks should look past political arguments over the film and look for the universal truths sprinkled throughout the film. There’s a scene where Forrest describes his running as “somehow making sense to people,” and a young guy, who might as well be Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate, follows Forrest and says, “This is a guy who has it all figured out. This is a guy who has all the answers! I’ll follow you anywhere, Mr. Gump.”

Materialism. Forrest has the perfect take on money and material wealth. There’s a scene where he opens a letter detailing his company’s investment in Apple (long before the iPod) and Forrest looks at it and says, “He got me invested in some kind of fruit company, so then I got a call from him saying, we don’t have to worry about money no more. So I said, ‘Good. One less thing.'” Is this not how we all should look at money?

Charity. Forrest says, “Now momma said there’s only so much fortune a man really needs and the rest is just for showing off.” So, he donates huge sums to the Four Square Gospel Church and the Bayou La Batre Medical Center — a religious and a scientific institution — with the classic understanding that “it’s not what you take when you leave this world behind you, it’s what you leave behind you when you go.” Whether it’s giving Bubba’s mom his share of the shrimping profits, or saving his buddies on the battlefield, Forrest constantly puts others ahead of himself.

Compassion. Forrest is the ultimate “clean slate” of kindness through an open mind. He says, “Lt. Dan didn’t like be called crippled, just like I didn’t like to be called stupid.” It’s like the great Atticus Finch line: “You never truly understand a man until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb inside his skin and walk around in it.” Instead of climbing inside of someone else’s skin, Forrest asks us to put ourselves in their shoes. As he himself says, “You can tell an awful lot about a man by his shoes. Where he’s going. Where he’s been.”

Natural Beauty. In such a beautiful world, so many of us can’t see the “Forrest for the trees.” Forrest tries to remind us of this as he pontifications on the landscapes during his cross-country trips, captured gorgeously in the Oscar-nominated cinematography of Don Burgess (Cast Away).

Sometimes it would stop raining long enough for the stars to come out. And then it was nice.

It was like just before the sun goes to bed down on the bayou, goes over a million sparkles on the water.

It was like just before the sun goes to bed down on the bayou, goes over a million sparkles on the water.

Like that mountain lake that was so clear, Jenny, it looked like it was two skies, one on top of the other.

And then in the desert, when the sun comes up, I couldn’t tell where heaven stopped and the earth began. It was so beautiful.

And then in the desert, when the sun comes up, I couldn’t tell where heaven stopped and the earth began. It was so beautiful.

Spirituality. Through this appreciation of natural beauty, Forrest becomes a man of great spirituality. He is slave to neither blind faith nor cynical doubt, most evident as he searches deep within his soul, only to conclude: “I don’t know if Mama was right or if it was Lieutenant Dan, whether we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating accidental-like on a breeze. But I think, maybe it’s both. Maybe both is happening at the same time.”

Spirituality. Through this appreciation of natural beauty, Forrest becomes a man of great spirituality. He is slave to neither blind faith nor cynical doubt, most evident as he searches deep within his soul, only to conclude: “I don’t know if Mama was right or if it was Lieutenant Dan, whether we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating accidental-like on a breeze. But I think, maybe it’s both. Maybe both is happening at the same time.”

Perhaps Forrest means we each have a path we’re supposed to follow in life, and our free will allows us to either veer away from it or follow it closely. Or, perhaps the quote is purposefully contradictory. Either way, it’s an answer we’ll never know on this earth. The best we can do is sit and think about such things. Forrest Gump makes us do that.

Pop Culture

Such universal truths and spiritual musings scratched a lot of people right where they itched. The public turned out in droves, to the tune of $329 million at the domestic box office and $677 million worldwide. Upon release, it was the 3rd highest domestic grossing film of all time (in sheer dollars), and when adjusted for inflation, it remains #24 all time, ahead of Mary Poppins (1964), Grease (1978), Thunderball (1965) and The Dark Knight (2008).

Naturally, the pop culture references began almost immediately. Sketch comedies have had a field day, form MAD TV‘s Gump Fiction, combining Forrest Gump with Pulp Fiction, to Saturday Night Live‘s The Lonely Island doing a duet with Michael Bolton.

Weird Al Yankovic had an entire song called “Gump,” spoofing the song “Lump” by the alt rock group The Presidents of the United States of America.

In 1999, Pixar’s Toy Story 2 (1999) spoofed Gump by having Slinky Dog say, “I may not be a smart dog, but I know what road kill is.” The WWE adopted “That’s all I have to say about that” as a catchphrase for Stone Cold Steve Austin and spoofed Gump in promoting Wrestlemania 21.

The Simpsons did their own spoof in 2002, featuring Homer as Forrest Gump.

Most importantly, the film inspired an entire restaurant chain, “Bubba Gump Shrimp,” joining the rare club of movies-turned-restaurants, from Popeyes (The French Connection) to Roy Rogers (various westerns). Looking out the window at the chain’s Times Square location, I couldn’t help but think of Forrest and Lt. Dan’s botched New Year’s Eve.

Legacy and Inspiration

After all the pop culture references, historical musings and homespun philosophies, we are still left with the same question posed by Entertainment Weekly — is Forrest Gump an “artificial piece of pop melodrama, or sweet as a box of chocolates?”

The answer, I believe, lies in the film’s tagline: “You’ll never look at the world the same after you’ve seen it through the eyes of Forrest Gump.” I think we will never look at “film greatness” the same after seeing it through the eyes of Forrest Gump. There are certainly films with more directorial vision (Citizen Kane), more filmic impact (Pulp Fiction), greater pop culture influence (The Graduate) and more entertainment value (Raiders of the Lost Ark). But if the notion of a “film spectrum” carries any water, Forrest Gump stakes out that rare middle ground of thematic profundity and popcorn inspiration, a recipe for the film’s #37 spot on the AFI’s 100 Cheers.

In Forrest Gump, Zemeckis, Hanks and company had achieved the trifecta that Aristotle described as “logos, ethos and pathos.” The film combines historical appeal (logos), craftsmanship from reputable filmmakers (ethos) and storytelling that plays on audience emotions (pathos). Like the very “fruit company” he invests in, Forrest Gump channels its inner Steve Jobs, meshing artful creativity with a shrewd business sense.

Thus, Gump is one of only a handful of films in the last quarter century to have both grossed the most money and won Best Picture in a given year. Even if it’s not your cup of tea, there’s no denying the movie provided answers for a ton of people. Sometimes, amidst all the art house masterpieces, we need a film that “has a way of explaining things so we can understand them.”

I will proudly proclaim myself a fan. Maybe it’s because it’s my father’s favorite movie, and his father before that, three generations watching the film religiously every time it airs on cable. Perhaps it’s because Tom Hanks is so charming that imitating his delivery of simple lines seems as natural and amusing as any I’ve seen. Or maybe, just maybe, it’s because the film helps me and millions of others make sense of decades of turmoil, greeting chaos with perspective, uncertainty with courage, and cynicism with hope for the future. As The Los Angeles Times predicted for the ’95 Oscars, “When in doubt, go with Gump.” (C) And that’s all I have to say about that.

![]()

Citations

CITE A: Tom Hanks AFI Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony

CITE B: Newsday‘s Jack Matthews on July 6, 1994

CITE C: Oscar book

CITE D: http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,570497,00.html

CITE E: Wang, Jennifer Hyland. A Struggle of Contending Stories: Race, Gender, and Political Memory in Forrest Gump. Cinema Journal – 39, Number 3, Spring 2000, pp. 92-115

CITE F: Roger Ebert’s original 1994 review: http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19940706/REVIEWS/407060301/1023

CITE G: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film