Director: Orson Welles

Writer: Herman J. Mankiewicz, Orson Welles (screenplay)

Producer: Orson Welles, Richard Baer, George Schaefer (RKO)

Photography: Gregg Toland

Music: Bernard Herrmann

Cast: Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorehead, Everett Sloane, Ruth Warrick, Ray Collins, William Alland, Erskine Sanford, Paul Stewart, George Coulouris, Fortunio Bonanova, Gus Schilling, Philip Van Zandt, Georgia Backus

The Rundown

- Introduction

- The Backstory

- Plot Summary

- Mammoth Roles

- The Beauty of Rosebud

- Screenplay

- Shared Depth of Focus

- A Master’s Control

- Slow Disclosure

- Movement Through Objects

- Transitions

- Blocking & Mise-en-Scene

- Progression

- Indicative Lighting

- Reflections

- Exhausting All Options

- Musical Score

- Pop Culture

- Art Imitates Life / Life Imitates Art

“[Citizen Kane] may be more fun than any other great movie,” wrote Pauline Kael, godmother of all film critics. I have a hunch, however, that your average viewer will agree more with Family Guy‘s Peter Griffin: “It’s a sled. There, I just saved you two long, boobless hours.” Indeed, so many in the mainstream reflect Joey and Rachel in Friends: “Have you ever tried to sit through Citizen Kane?” “I know. It’s really boring, but it’s like a big deal.”

Since 1962, Citizen Kane has held the #1 spot on the Sight & Sound international critics poll, while topping the AFI Top 100 for ten years running. For this, the film has become cultural shorthand for perfection, with any “best” item instantly called: “The Citizen Kane of ____.” Meanwhile, the film doesn’t even crack the Top 25 of fan polls like the IMDB or Empire — a clear contrast to the film’s unanimous scholarly exultation.

With the highest expectations of any movie in existence, it should be no surprise that many casual viewers are mystified by the hype. I, too, battled this beast as a teenager and lost to my drooping eyelids, oblivious to the visual mastery unfolding before me, the stuff which untrained eyes cannot yet see.

But trust me. Citizen Kane is the single most important film for you to understand, because it carries the very DNA required of everyfilm critic, the blueprint for any serious filmmaker and the standard by which scholars judge the “great movies.” Understand this one, and you’ll have unlocked the most challenging end of the film spectrum. You’ll be well on your way to understanding the rest of the listology kings, the art masterpieces and the critical favorites that have mystified you for so long.

The Backstory

To start, realize that part of the film’s allure comes with its one-of-a-kind backstory. Filmmakers will forever adore the idea of a maverick 25-year-old Orson Welles, the boy genius who became a household name with his 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, being given the most lucrative motion picture contract ever, along with cart blanche (complete control) to direct his debut film exactly as he wished. Thus, reviews of the film almost always compare Welles’ first Hollywood camera to the most expensive “toy train” or “paint box” he had yet encountered.

Further boosting the hype is the fact that this young brainchild had the audacity to mock the most powerful man in America, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst (rival of Joseph Pulitzer). When Hearst saw the similarities between himself and the film’s central character — both were newspaper giants with three-part names, failed political careers, public marital problems and gigantic home fortresses stuffed with material relics they never saw — the media mogul tried to get the film destroyed. When that didn’t work, Hearst’s next option was to trash it with terrible reviews, leading to the film tanking at the box office, and a successful Oscar night sabotage.

Though Kane made Welles the first to earn Oscar nominations as producer, director, writer and lead actor all for the same movie, it was upset for Best Picture by the inferior How Green Was My Valley (1941). Now, 70 years later, Welles has gotten the last laugh, as his charicature of Hearst has become better remembered than the man himself.

Plot Summary

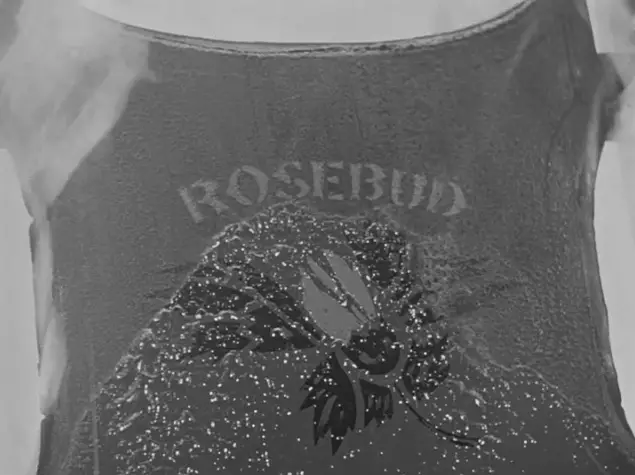

The film opens with the most famous one word in movie history, “Rosebud,” uttered in the dying breath of millionaire media mogul Charles Foster Kane (Welles). Immediately, reporters compile a newsreel to recap the major events in Kane’s life. But something is missing. Rosebud. Who is it? What is it? And why did it mean so much to Kane that he would say it on his death bed?

To crack this mystery would be to unlock the personal core of the man, the most public of all private lives. And so we follow journalist Jerry Thompson (William Alland) on his vital research venture, first to the Thatcher Library, where he reads the memoirs of Kane’s adopted guardian, Walter Thatcher (George Coulouris), and then to interviews with Kane’s journalist colleagues, Mr. Bernstein (Everett Sloane) and Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten), and his second wife, Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). Their accounts weave a picture of an ambitious, arrogant, self-righteous man who longed for a happiness that had been ripped from his grasp long ago.

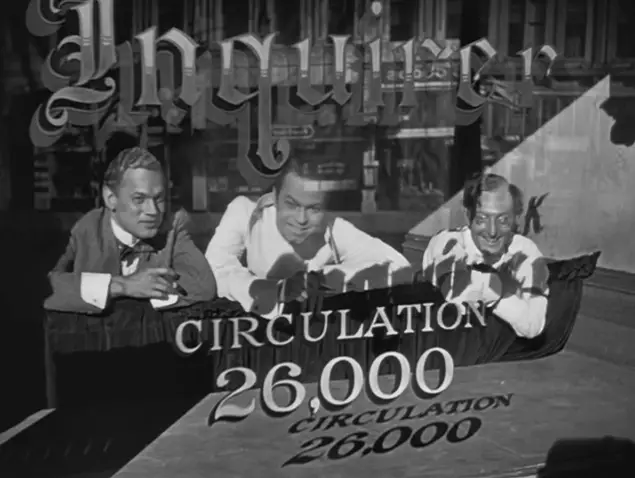

It seems Kane was happiest when he was the poorest, a young kid playing with his sled on the snowy, rural banks of a carefree childhood. We go to the moment that all changed, in 1871, when mother Mary (Agnes Moorehead) sends him to live with the wealthy Mr. Thatcher so that he will never have to worry about money again. Despite the newfound wealth, young Kane resents the move. And by his early ’20s, he’s operating a newspaper, The Inquirer, railing against the likes of Thatcher with its populist positions.

Kane’s Inquirer launches with a “Declaration of Principles,” the likes of which should be followed by today’s news outlets. Gradually, he loses these principles in favor of a new mantra: ”If the headline is big enough, it makes the news big enough.” He builds a media empire on this type of sensational yellow journalism, rubbing elbows with history’s biggest figures (Teddy Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler) and having so much influence on national opinion that he is able to push his country into the Spanish American War. When a correspondent wires, “There is no war in Cuba,” Kane responds as Hearst did: “You provide the prose poems, I’ll provide the war.”

These journalistic untruths soon spill over into his personal life. After marrying Emily Norton (Ruth Warrick) and having a child, Kane sets his sights on political office, running for governor against corrupt political boss Jim Gettys (Ray Collins). He loses after being exposed for an affair with young shopgirl Susan (Comingore), echoing his own advice to Emily: “You never shoulda married a newspaper man. They’re worse than sailors.” Two weeks after divorcing Emily, Kane takes Susan for his second bride.“Takes” is the key word, as Susan quickly becomes just another object of his ambition.

Despite her clear lack of singing talent, she’s pushed to become the star for Kane’s new $3 million Chicago opera house. Like Hearst, Kane uses his media influence to inflate the image of Susan and eventually constructs a massive castle to her, located on a man-made mountain on the west coast, borrowing its name from the estate of Kubla Kahn — Xanadu.

In this vast space, Kane and Susan grow old, until Susan too leaves him out of loneliness of their cavernous existence. In his final days, Kane is not surrounded by family, but by the hoards of relics he’s bought only to store in crates, stuff he cannot take with him when he dies. His death leaves all of his worldly possessions for others to sift through, and in the end, Thompson and his fellow reporters (including a young Alan Ladd) are left scratching their heads as to the meaning of “Rosebud.” They settle on the notion that, “Mr. Kane got everything he wanted then lost it. Perhaps Rosebud was something he couldn’t get or something he lost.” In the final shot, the latter is confirmed.

Mammoth Roles

Such an expansive, complex story required an expansive, complex performance. Kevin Spacey remains in awe at the size and scope of Welles’ performance, saying, “The dynamics of that character that he plays are gigantic.” In fact, the performance is so seamless we almost forget it’s an actor on screen.

“There’s this extraordinary performance which people seem to take for granted,” says writer/director/critic Peter Bogdanovich. “I mean Orson ages from 25 to 85 in this movie, and he’s totally believable at every phase of it.” (E)

With the help of some superb make-up, Welles plays a range of emotions over different phases of Kane’s life. Look at the charm as he grows The Inquirer. The tenderness as he talks to Susan in her room. The self-denial as he chases Gettys after being caught in his affair: “I’m Charles Foster Kane! I’m no cheap, crooked politician trying to save himself from the consequences of his actions!” Welles broke his ankle running down the stairs in that scene, which when combined with a back brace to stiffen his movements, allowed him to play the elderly Kane.

“When I first saw the film, I was feeling more for Orson Welles himself, acting in the film,” Martin Scorsese said. “I liked him personally.”

Welles also surrounds himself with an amazing supporting cast, which serves as a “who’s who” of Hollywood’s Golden Age. When Welles decided not to star in his sophomore effort, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), he brought Joseph Cotten back as the leading man. The snowball effect landed Cotten leading roles in two phenomenal films, Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and again across the screen from Welles in The Third Man (1949). It’s no coincidence that two of the most memorable scenes in Kane come with Cotten. Who can forget Cotten waking up from a drunken stupor and approaching Kane at the typewriter? Who can forget his breakdown of Kane’s arrogance as they return to the newsroom in post-election failure?

Cotten wasn’t the only one Welles liked enough to bring back for Ambersons. Agnes Moorehead, whom mainstreamers know from TV’s Bewitched (1964), appears in just one scene in Citizen Kane, but her maternal sadness is enough to carry the entire weight of Kane’s childhood. Similarly, Welles liked character actor Everett Sloane so much as Mr. Bernstein that he later brought him back in The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

As the mistress Susan Alexander, Dorothy Comingore is a shrill-voiced precursor to Jean Hagen in Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and a foreshadowing of Welles’ own doomed relationship with Rita Hayworth. It was actually this performance that enraged Hearst the most, as Susan was a clear nod to Hearst’s second wife, Marion Davies, who was actually a very talented performer and whose comparison to Susan became a lightning rod for Hearst’s attacks and Welles’ biggest regret.

Still, oddly enough, the main figure driving the narrative is hardly a character at all. No, not the faceless investigator who carries us through the picture, but rather the one-word mystery he chases.

The Beauty of Rosebud

Never has a twist so frustrated first-time viewers — and taught them to reconsider their initial impressions in a deeper way — as the revelation of “Rosebud.” The mystery yarn is unraveled by a faceless investigator and revealed only to the audience: a name on a sled. At first, the revelation appears mundane, maybe even random. Of course, we’re warned at the start: “It’ll probably turn out to be something very simple.” But is it really that simple? And what can be learned from the simple things in life?

It’s not a twist that smacks you over the head, which is why the Peter Griffins of the world miss the jaw-dropping sensation that became so trendy in the ’90s with The Shawshank Redemption, The Usual Suspects, Fight Club and The Sixth Sense. Instead, it’s a twist that makes you think. It’s one with more meaning. And it’s the type of thing Kane asks us to do: strip down tangible images to find the hidden meaning underneath, the magic trick up Welles’ sleeve. Welles himself dismissed the “Rosebud” sled device as a “dollar-book Freudian gag,” and as Nigel Andrews writes for Slate.com, “It was the single detail … [Welles] freely attributed to screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, whom he fought for credit over almost every other part of the film.” (B)

It’s not a twist that smacks you over the head, which is why the Peter Griffins of the world miss the jaw-dropping sensation that became so trendy in the ’90s with The Shawshank Redemption, The Usual Suspects, Fight Club and The Sixth Sense. Instead, it’s a twist that makes you think. It’s one with more meaning. And it’s the type of thing Kane asks us to do: strip down tangible images to find the hidden meaning underneath, the magic trick up Welles’ sleeve. Welles himself dismissed the “Rosebud” sled device as a “dollar-book Freudian gag,” and as Nigel Andrews writes for Slate.com, “It was the single detail … [Welles] freely attributed to screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, whom he fought for credit over almost every other part of the film.” (B)

While “Rosebud” may appear a red herring (like one of Hitchcock’s “MacGuffins”), it actually provides the key to unlocking Kane’s character. And what a character it is. There’s a reason Premiere magazine voted Charles Foster Kane the #12 Greatest Movie Character of All Time. His tragic character study has influenced everything from Michael Corleone in The Godfather (1972) to Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood (2007) — three lonely emperors of man-made estates, three men left to ponder the consequences of their choices, three products of an American dream perverted.

You need not be a lonely mogul to appreciate this theme. Anyone who has ever had an imaginary friend, a favorite blanky or stuffed animal can relate. All who have gone from the innocence of youth to the weight of adulthood can relate to yearning for a simpler time. Even FDR said that in times of stress (you know, little things like World War II and The Great Depression) he used to think about his childhood sledding down a hill at Hyde Park in order to fall asleep. This is what “Rosebud” represents, a theme Sam Peckinpah would articulate best in The Wild Bunch: “We all dream of being a child again. Even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all.”

In this light, certain scenes take on new thematic weight upon second look. When Thatcher comes to take Kane away, note how the young Kane symbolically uses his sled as a shield to push Thatcher away. Then, watch as the time-lapse photography shows his sled slowly buried by snow; his childhood buried by the sands of time.

Later, when Kane meets Susan, note that he’s on his way to a warehouse to look at his old childhood belongings. “I went out tonight looking for my youth, and I found you.” When she says her mother is the one who wanted her to be a singer, it inspires Kane, on a deep psychological level, to make her into one.

Welles symbolically places the snow globe on Susan’s dresser, next to a photo of her as a child. This is the first time that the prop enters Kane’s life, and he doesn’t even know it.

It isn’t until Susan leaves him that Kane finds the snow globe and ties it to his own childhood. Muttering “Rosebud” under his breath, he picks up the globe with tears in his eyes. Like marking a baseball scoresheet, Kane’s “K” jewelry hangs upsidedown and backwards. Mighty Kane has struck out.

Who does Kane blame for losing Rosebud? Losing his innocence? Thatcher. As Kane hands ownership of his newspaper to Thatcher, he says, “I always gagged on that silver spoon … if I hadn’t been very rich, I might have been a really great man.” He realizes — at least momentarily — that money cannot buy happiness. As he says, “It’s no trick to make a lotta money when all you want is to make a lotta money.”

Screenplay

This unraveling of the “Rosebud” mystery and the deep character study of Charles Foster Kane are just two reasons the script is so lauded. Add eloquent dialogue and a groundbreaking structure, and it’s a no-brainer why Kane was recently ranked #4 on the WGA’s Greatest Screenplay of All Time, one spot ahead of All About Eve (1950), written and directed by Mankiewicz’s brother, Joseph.

The script for Citizen Kane blew the concept of narrative structure to pieces. Rather than tell their tale chronologically, Welles and Mankiewicz open the film with the very end of the protagonist’s life, a move copied by countless films since, most famously Sunset Blvd. (1950) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

After this, Welles and Mankiewicz give their ballsiest move yet — summarizing the entire story you’re about to see — at the outset of the movie! This is something that had not been done before and, as far as I know, has not been done since. It’s done in the form of the “News on the March” newsreel.

From here, the script dives into the newsreel’s material and expands it, dipping in and out of flashback through the interviews with Kane’s closest survivors. It ruptures chronology so much that we often forget exactly when we are in flashback and when are not. We forget whose flashback we’re in and why. And at times, we are privy to such private info that we must be within Kane’s own memories, his life flashing before his eyes. It is truly amazing how seamlessly this is done.

Of course, this may also be why so many first-time viewers are put off by the film, particularly the twilight of Susan and Kane in Xanadu, where Welles himself feels the need to throw in a hollow-eyed screeching bird for anyone who made have nodded off in theaters. Nonetheless, these fractured narratives and interwoven memories allowed countless films to follow, maybe even some of your favorites: All About Eve (1950), Rashomon (1950), Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Nashville (1975), Pulp Fiction (1994), Magnolia (1999), Memento (2000).

Not only is this notion of fractured memory expressed in narrative structure, it’s also eloquently articulated in the dialogue. As Leland says:

Leland: I can remember absolutely everything, young man. That’s my curse. That’s one of the greatest curses ever inflicted on the human race: memory.

Bernstein has a similar take:

Bernstein: Old age…it’s the only disease that you don’t look forward to being cured of.

Try something. Read Kane‘s script and count how many words it takes before you hit the AFI’s #17 Movie Quote of All Time. I’ll give you a hint — you only need read one word. “Rosebud” may be the most famous opening line in movie history, but it is just one word in a script full of zingers. Take this exchange:

Kane: You long-faced, overdressed anarchist.

Leland: I am not overdressed.

Or this one:

Leland: I didn’t know Charles was collecting diamonds.

Bernstein: He’s not. He’s collecting someone who’s collecting diamonds.

Some of the brilliance is easy to overlook. For instance, Susan initiates the affair by inviting Kane in for some “hot water” after he’s been splashed with mud on the sidewalk. Later, when the affair is exposed, she complains that her name “will be dragged through the mud.” Easy to miss on first watch, but devilishly intentional on second look.

Other times, the writing is right there in the spotlight, just waiting to be admired for its eloquent prose. Take Bernstein’s nostalgic account of a woman in a white dress, no doubt inspiring Mitchum’s voiceover for Jane Greer’s entrance in Out of the Past (1947), or DeNiro’s voiceover for Cybill Shepard’s entrance in Taxi Driver (1976):

Bernstein: One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry. And as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in. And on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all. But I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.

For all this, Pauline Kael, author of The Citizen Kane Book and Raising Kane, argues that Mankiewicz deserves more credit than Welles. Even on Oscar night, the film’s sole Oscar (Best Screenplay) went to Mankiewicz, until arbitration by the Writers Guild forced it to be shared with Welles. (B)

Despite Kael’s lobbying, I have to side with Peter Bogdanovich, who refuted Kael’s argument in his 1972 book The Kane Mutiny, re-championing Welles as the film’s true master. To me, the litmus test is simple — if you give the same script to a different director, will it be a completely different film? Never does that hypothetical hold more true than here.

Shared Depth of Focus

If Mankiewicz is to deserve a slice of the credit, Director of Photography Gregg Toland deserves just as big a piece. Fresh off an Oscar for Wuthering Heights (1939) and groundbreaking work on The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Toland was the perfect match for this hot-shot rookie, and Welles enjoyed their collaboration so much that he offered to share his title card in the end credits.

Together, the two broke the tradition of ’40s Hollywood that a movie’s director should be transparent, that viewers shouldn’t even notice the camera’s involvement. Instead, Welles and Toland went the opposite route, hoping to draw as much attention to the camera as possible, cooking up dramatic angles and pioneering the possibilities of “deep-focus photography.” Expanding upon Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939), Welles and Toland showed just what was possible by keeping all parts of the image — foreground to background — in focus at the same time.

If you ask me, Citizen Kane creates an illusion of 3D that is more three-dimensional than most of today’s 3D movies. And you don’t even need to wear those plastic glasses.

The result is a black-and-white cinematic space that is so crisp that it doesn’t date a bit. Thankfully, cinema survived a push by Ted Turner in the ’80s to “colorize” black and white films, at which point Welles made his own dying wish: “Keep Ted Turner and his goddamned Crayloas away from my movie.”

A Master’s Control

As lauded as Kane is for its look and its script, the thing that catapults it to the top of best lists is Welles’ directorial vision. Welles commands every frame, hitting us so fast with clever directorial concepts that professors cannot hope to explain them without a pause button. Kane has to be the most screened film of any film class, teaching generation after generation that there is, in fact, another way of “seeing” films.

“Citizen Kane will always be something that demands attention and respect and admiration for another way to see the world through the cinematic eye,” said Martin Scorsese. Watching Kane was the moment he “really discovered what a director does.”

“Not just every scene, but every shot has an idea,” said the late Sydney Pollack. “There’s a concept and an idea being executed at every second of that film.” (E)

“There’s never been a film that I’m aware of that if you watch it for the 138th time, you still see something new that you haven’t noticed,” Richard Dreyfuss tells the AFI. (E)

This is what has made the film so rich to dissect over the decades. Its power does not dissipate after one viewing. It grows the more you see it. Roger Ebert’s audio commentary is as good as any explanation, but here are a few of the genius directorial touches I’ve noticed over the years.

Slow Disclosure

The opening might be the most famous in all of movie history, as Welles slowly approaches Xanadu, moving up the mountain and closer to the castle with a series of dissolving images. Once he reaches the outside of Kane’s bedroom window, we get a brilliant bit of trickery — a seamless dissolve from outside to inside, using the window as a visual anchor. As snow covers the screen, we think we’re looking at the inside of a snow globe, but as the camera pulls back, we realize that the snow is superimposed over Kane’s entire room (reflections of his snowy childhood memories).

Movement Through Objects

The perceived movement “through” the bedroom window is the first of several suck tricks. During the interview attempt with Susan at the El Rancho cafe, Welles provides a brilliant crane shot that starts on a mural of Susan outside the restaurant, moves up the side of the building, pushes through a rooftop sign (rigged to pull apart) and moves in on a glass roof that shows Susan sitting at a table below. The blur of rain and lightning transports us through the glass inside. See the camera move here.

Welles uses a similar “single take” when Kane’s mother signs custody over to Thatcher. It starts with a shot of young Kane playing in the snow, the camera appearing to be outside. A dolly back reveals that we’re really looking out a window. We pull back further to reveal Kane’s parents and Mr. Thatcher, then further yet to move through a table. The table was specifically designed to pull apart then reassemble after the camera’s passing (if you look closely, you can see the hat moving). The whole time, Kane remains visible out the window in the background, thanks to the deep-focus photography. As Kane’s mother signs him away to Thatcher, his father moves into the background to symbollically shut the window on their son. The fact that it’s all done in a long single take (without a single cut) is an incredible feat of filmmaking. See the camera move here.

Transitions

Welles comes up with a number of clever transitions between scenes. My favorite is the zoom in on a photograph of the The Inquirer‘s rival newspaper staff, The Chronicle. With a barely noticeable dissolve, the photo comes to life in a live-action shot of the men as they join The Inquirer‘s staff.

The same technique is used again later, only now Welles goes in the opposite direction, going from live-action shot into a newspaper photo. As Kane’s affair with Susan is exposed, Susan’s real-life door dissolves into a newspaper photo of the same thing. How fitting that when Kane is on the rise (hiring new staffers), photos come to life, and when he is on the decline (caught in an affair), life becomes printed.

Sometimes the genius transitions come in such a rapid succession that we hardly notice them. From Young Kane’s sled piled with snow, we cut to a shot of the camera physically behind wrapping paper (yes, Welles actually unwraps a “camera” — his most expensive “paint box” indeed). As it’s unwrapped, we see Young Kane with a fancy new sled, bought for him by Thatcher. We tilt up to see Thatcher, his height exagerated by a low-angle shot and the actor standing on an applebox. Welles then hits us with a 20-year flash-forward between the time Thatcher says “Merry Christmas” and “Happy New Year.”

A clever transition also bring us into the high point of Kane’s career: his speech at the political rally. This scene itself is a wonder to behold, with that giant “KANE” poster behind Kane, the real man swallowed in the image of himself. Note also the resourceful recreation of Madison Square Garden, using a giant matte drawing with lights shining through little holes to create the impression of movement in the crowd. As the camera moves in for a real low angle next to Kane’s podium, he appears towering and proud. His ego is at an all-time high.

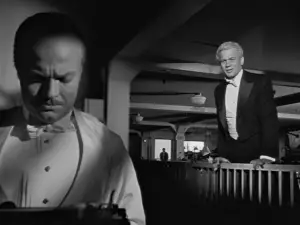

Blocking & Mise-en-Scene

As seen at the political rally, Welles blocks his actors with a mise-en-scene (composition of all elements in the frame) that visually expresses things about his characters. For instance, when we first meet Kane as an adult, there is a great power struggle between he and Thatcher. The scene begins with Thatcher towering above him, accusing him, “Is that really your idea of how to run a newspaper?” By the end of the scene, Kane rises up to Thatcher’s level, only now Kane is taller and symbolically more powerful.

When Kane signs over his newspaper to Thatcher, there is a brilliant display of using three-dimensional space and mise-en-scene to express his character’s emotions. As Kane walks into the background (as his father had when he signed Young Kane over to Thatcher many years before), Welles creates the optical illusion of Kane shrinking. This is in part due to perspective and part due to the construction of oversized windows on the back wall. The effect is clear: Kane feels “small.” Then, the moment Thatcher reads a clause that will allow Kane to maintain some control, Kane walks back toward the camera, growing larger as his control is restored.

Welles and Toland also shot from lower angles, literally carving out the floor and placing the camera below floor level. This allowed them to show the ceilings of their sets and made all the characters look a little more mythical. Watch how Welles’ choreography is symbolically significant. As Kane moves about his campaign headquarters after an election loss, his body grows and shrinks in size depending on the words being spoken. When he says, “I’ve set back the sacred cause of reform,” he walks deep into the frame and becomes small. But when Leland says, “You talk about the people as though you own them,” Kane appears so big that we can only see up to his knee. Finally, when Leland says, “You don’t care about anything except you,” Kane is large once again.

Finally, in the spacial emptiness of Xanadu, watch how Kane walks into the background, dwarfed by an oversized fireplace. For all the grandeur of his possessions, he is a small, pitiful man.

Progression

Perhaps the most brilliant sequence in the film is the montage of Kane and Emily aging at the breakfast table. Welles sees to it that in each segment of the montage, the table grows longer and longer, until by the end of the montage, they are sitting miles apart. It symbolizes their growing “distance” from one another.

Indicative Lighting

Note how Welles uses lighting to express thematic ideas. When Kane writes his Declaration of Principles, note that there is a shadow on his face — foreshadowing the false promise that this document is to become. We literally cannot see his face at the very moment he’s declaring what he stands for!

Kane’s face is again covered in shadow as his affair is exposed right in front of his wife. She’s dressed in the purest of white; he’s in the darkest black.

Later, Kane stands in complete darkness as he loses himself in a lone standing ovation for Susan’s lackluster opera performance.

Reflections

Sometimes, the directorial ideas can be simple, yet effective. Note how Bernstein literally reflects in his desk as he figuratively reflects on a story from his past.

Another reflection is prominent during Leland’s criticism of Kane during the dance number. He symbolically blows smoke over Kane’s reflected image in the window, disapproving of the way Kane is giving into the excesses of his success.

The most bizarre example comes in the opening, where a dying Kane drops the snow globe and it shatters on the floor. As the remnants of the globe show the reflection of Kane’s nurse, we realize this is going to be a movie of crazy angles and perspectives we have never seen before.

Finally, after a backtracking shot of Kane leaving Susan’s room, Welles provides his best use of mirrors yet. Watch how Kane exits the frame to the left, only to become visible again in a well-placed mirror. This leads to the film’s penultimate image of Kane entering a hall of mirrors, creating the illusion of infinite Kanes: the many sides of Charles Foster Kane. It was a trick he would later perfect in The Lady from Shanghai (1947), and which Mankiewicz’s brother would steal for the final shot of All About Eve.

Exhausting All Options

The above examples are but a few moments of Welles’ brilliant vision. In the end, you realize Welles has exhausted just about every mode of filmmaking there is: comedy, drama, mystery, romance, noir expressionism, shades of horror, the newspaper caper, the political thriller, newsreel footage, opera, a song-and-dance musical number, animation mixed with live action, even shadow puppets on a wall.

It’s become cliche to say that great masters of any craft dot every “i” and cross every “t.” And yet, Welles does this (literally) by having young Kane chuck a snowball at the roof of his mother’s boarding house.

Musical Score

The above snowball splats in perfect timing with the musical score, penned by Welles’ good friend Bernard Herrmann. The two had worked together in radio at Mercury Theater, where Herrmann provided the music for Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast.

The score is at times brooding (“Prelude”), nostalgic (“Thatcher Library”) and triumphant (as in the “Overture”). It has since become a mainstay in film retrospectives, from Chuck Workman’s “100 Years at the Movies” for Turner Classic Movies, to John Williams’ tribute at the Oscars. Herrmann also wrote the “Aria from Salammbo” opera piece for Kane, performed by Comingore and dubbed by Jean Forward.

The music earned Kane an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score, but lost to Herrman’s other score for another film, The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Thus Kane marked the start of Herrmann’s illustrious career, leading to such masterworks as Vertigo (1958), Psycho (1960) and Cape Fear (1962). If Taxi Driver (1976) was the final curtain of Herrmann’s career, Citizen Kane is a fitting front bookend. Spanning from Welles to Scorsese, with a whole lot of Hitchcock in between, is not a bad way to spend a career. Herrman’s career is just one more historic notch in Kane‘s belt.

Popular Culture

You can be watching anything, in any genre, and find a reference to Citizen Kane. Usually, it’s a nod to “Rosebud,” like this one in Field of Dreams (1989).

Of course, there are the aforementioned Friends and Family Guy references.

When the cast of The Simpsons appeared on BRAVO’s Inside the Actor’s Studio, they said they could probably reconstruct 75% of Citizen Kane based off spoofs in their show. Other cartoons, like Pinky and the Brain, have followed suit, planting the seed of Kane long before we’re in on the joke.

Indeed, Kane is so engrained in our culture that sometimes we take it for granted. Such was the subject of this hilarious skit from Comedy Central’s Kids in the Hall.

Internationally, cultural references to Kane pop up in a number of films, most famously in Francois Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973). Here, the protagonist (a filmmaker) dreams of a childhood experience where he sneaks up to the gate of a Paris movie theater to steal production photos of Citizen Kane.

Still, my favorite reference comes in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994), where a distraught Johnny Depp approaches Orson Welles (Vincent D’Onofrio) at a bar for some inspiration. Welles tells him, “You know, the only film of mine where I had total control, Kane, the studio hated it, but they didn’t touch a frame. Ed, visions are worth fighting for. Why spend your life making someone else’s dreams?”

Art Imitates Life / Life Imitates Art

Indeed, the cultural significance of Kane is inextricably tied to the cultural significance of Welles himself, the greatest example of art imitating life, then life imitating art. Perhaps Welles was so perfect to take on the mantle of Kane because he was himself more similar to Kane than even Hearst. Perhaps fate had chosen Welles to foreshadow his own future and create cinema’s first autobiographical statement. Perhaps there was a bit of Rosebud-longing in Welles himself, having been robbed of a “normal” childhood after gaining fame at such a young age.

The myth of his childhood is legendary — declared a child prodigy at age 3, learned magic tricks from Houdini at age 5, lost both his parents by the time he was 15, went to New York to “present history’s greatest plays and stage them for the common man” in his late teens, formed the Mercury Theater at age 22, expanded it into a CBS radio show later that year, directed “Julius Caesar” to rave reviews at age 23 (subject of the film Me and Orson Welles), and convinced millions of Americans that aliens had invaded New Jersey in his radio broadcast of War of the Worlds, earning him an unprecedented Hollywood movie contract at age 24. (A)

“We still at this point in history can’t truly fathom the extent of [his] success,” said writer Richard France. “He was a name known in the same breath as Roosevelt. That’s how successful he was. That’s how prominent he was. Yes, it peaked at the age of 25, and he became known a year or two later as America’s youngest has been.” (A)

In so many ways, Welles was a larger-than-life figure that had a larger-than-life fall. This is beautifully chronicled in the documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane. After a dream deal on Kane, the rest of his career would be mired in studio meddling and creative clashes. Welles was even removed from his sophomore effort, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

“Orson was smarter than everybody else, and they knew it, and people were jealous,” said Gary Graver, another cinematographer in Welles’ career. “He didn’t need a producer; he was a producer. That cut the other guy out. And he wanted total control.” (C)

Critic David Thomson sees an almost masochistic, self-sabotaging quality to Kane: “The film is shot through with [Welles’] vast, melancholy nostalgia for self-destructive talent. Kane goes out of his way to destroy and isolate himself by calling Gettys’ bluff.” (D)

Time and again, Welles called the bluff of the studios, and they made him pay. He remained his own kind of megalomaniac, so beholden to his own artistic vision that none of his films ever made any money. He was the exact opposite of the popular Hollywood phrase, “make one for me, make one for the studios,” because he made every movie for himself, writhing at the thought of compromise, and paying a price for it. In the end, Welles’ career is both a creative zenith and a cautionary tale.

“I’ve wasted the greater part of my life looking for money and trying to get along, trying to make my work from this terribly expensive paintbox, which is a movie,” Welles said. “And I’ve spent too much energy on things that have nothing to do with making a movie. It’s about 2 percent moviemaking and 98 percent hustling. That’s no way to spend a life.”

Regardless of whether it’s a way to “spend a life,” his “life examined” is invaluable. In so many ways, Welles was a martyr to the notion of cinema as a vessel to explain the human condition. Such larger-than-life tales of larger-than-life men form case studies to unlock our existence. How exactly should we spend our lives? The question reveals why so many prefer reading about these tragic figures, rather than becoming them. Why we pick up tabloids not unlike Kane’s Inquirer and live vicariously through celebrity. Why filmmakers strive to match his success, if not his demise. And why we critics feel the unique urge to explain these filmmakers among men, these artists who, as Thomson writes of Welles, “inhaled legend — and changed our air.” (D)

Citations:

CITE A: The Battle Over Citizen Kane, DVD featurette, Citizen Kane Special Edition

CITE B: The Mark of Kane, Nigel Andrews, The Financial Times, pulled from Slate.com, http://www.slate.com/id/2293387

CITE C: “Edge of Outside,” Turner Classic Movies Documentary

CITE D: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE E: AFI 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)