Director: Frank Darabont

Writer: Stephen King (novella), Frank Darabont (screenplay)

Producer: Niki Marvin (Castle Rock, Columbia)

Photography: Roger Deakins

Music: Thomas Newman

Cast: Tim Robbins, Morgan Freeman, Bob Gunton, William Sadler, Clancy Brown, Gil Bellows, Mark Rolston, James Whitmore, Jeffrey DeMunn, Larry Brandenburg, Neil Giuntoli, Brian Libby, David Proval, Joseph Ragno, Jude Ciccolella

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Career Roles

- Darabont the Writer

- Darabont the Director

- Mise-en-Scene

- Symbolic Cuts

- Power Reversal

- Familiar Image

- Slow Disclosure

- Indicative Lighting

- Rising Above the Walls

- The Beauty of Music

- Themes & Metaphors

- ‘Hope is the Best of Things’

- Pop Culture

- Positive Word of Mouth

- Criticisms & Responses

- Legacy

“Hope is a good thing. Maybe the best of things. And no good thing ever dies.”

Only a select few films ahave been called “the most beloved of all time.” Annual TV airings earned the title for The Wizard of Oz (1939) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), while box office receipts have made strong cases for Gone With the Wind (1939), The Godfather (1972) and Star Wars (1977). But in the internet age, a new generation of Millenials holds up a new contender: The Shawshank Redemption.

Bear in mind today’s viewers consume movies in an entirely different way than those who went to see Gone With the Wind. A trip to the movies has taken a backseat to the swarm of Netflix, DVR, On Demand and Hulu+. Within seconds of the end credits, our votes have already been cast on IMDB. We’ve already “liked” it on Facebook. Hell, we probably Tweeted what we thought of the movie while we were watching it.

Only in this new culture of rapid film consumption and instant web response can a film like The Shawshank Redemption rise the ranks of reverence to do war with the listology kings of academic glory. Thus is why I’m opening The Film Spectrum with Shawshank alongside Citizen Kane. In many ways, Shawshank has become the Citizen Kane of IMDB.

More than half a million viewers, spawned by positive word of mouth, have flocked to the site to rank the film No. 1. Its 9.2 rating may be tied for first with The Godfather (my pick), but its 596,000 total votes trump even the extended Corleone Family. With hundreds of thousands more votes than any other film on the site, the people have spoken. To them, Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption is not only a good film, it’s the best of films, and they’ll make sure it never dies.

Plot Summary

Originally a Stephen King novella titled Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption (from the same 1982 anthology that included Stand By Me‘s source material “The Body”), The Shawshank Redemption introduces us to Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), a sharp banker falsely sentenced to two life terms for the double-murder of his wife and “the fella she was banging.” He’s sent to Shawshank State Prison in 1947, where the rules are enforced by “colossal prick” Byron Hadley (Clancy Brown) and made by the corrupt Warden Norton (Bob Gunton), a religious hypocrite who says, “Put your trust in the Lord. Your ass belongs to me.”

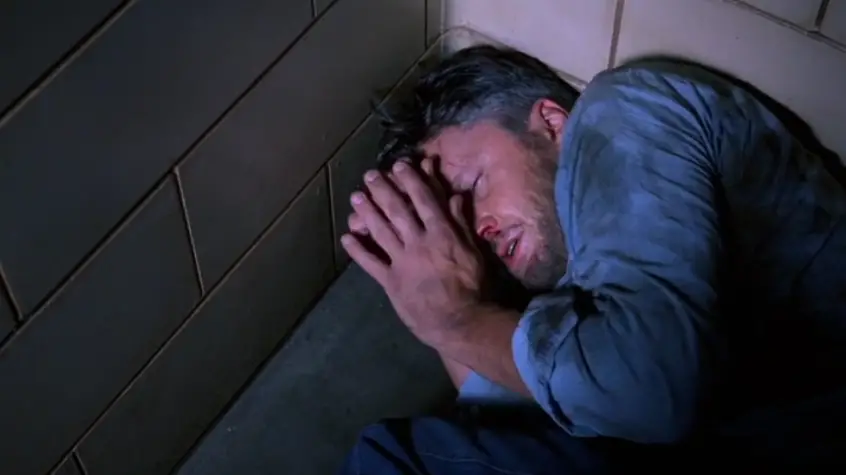

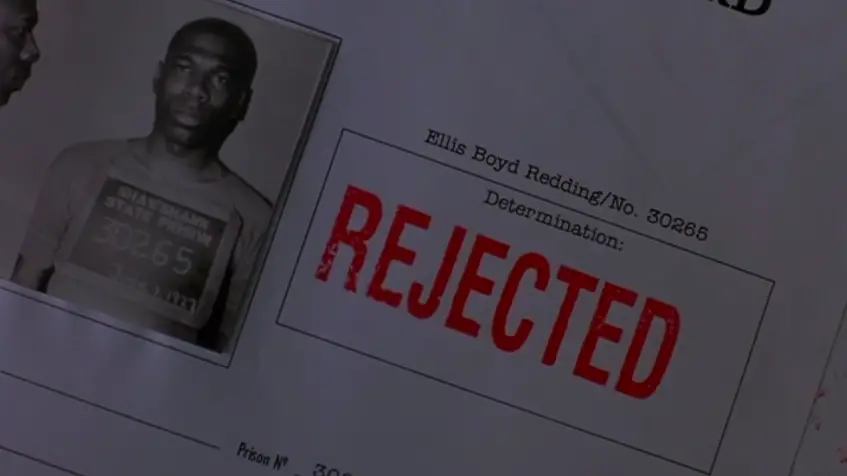

Andy spends his first two years (unsuccessfully) dodging a gang called the Sisters, led by rapist Bogs (Mark Rolston), who is not even homosexual (“You have to be human first. They don’t qualify”). Throughout the ordeal, Andy confides in Ellis Boyd Redding, known simply as “Red” (Morgan Freeman), a man who knows how to smuggle things inside the prison walls, a “regular Sears Roebuck.” At first, Red doesn’t think much of Andy, calling him “a tall drink of water with a silver spoon up his ass,” but soon they develop a male bond rare to movies. It’s Red whom Andy first opens up to, asking for a tiny rock hammer for his hobby of sculpting stones and, after a screening of Gilda (1946), posters of Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe and Raquel Welch.

In the spring of ’49, Red fixes it so that he and the guys are assigned to outdoor detail to resurface the roof of a factory. It’s there that Andy wins over the rest of the inmates by haggling a round of beers in exchange for giving tax advice to Captain Hadley. Soon, all the guards at Shawshank are coming to Andy for his accounting knowledge, including Warden Norton, who hires Andy to keep the books on his corrupt money-laundering deals. In exchange, Andy convinces the Warden to expand the prison library, run by the institutionalized, bird-loving Brooks Hatlen (James Whitmore).

One day, a fiery young thief, Tommy Williams (Gil Bellows), comes to join them at Shawshank. He claims he once shared a cell with a killer who bragged about killing a banker’s wife and her lover, and laughed at how it was falsely pinned on the banker. Andy brings the story to the attention of the Warden, hoping for his acquittal, but the warden cracks down hard, fearing he’ll be exposed for corruption. At his breaking point, Andy orders a length of rope and decides whether to “get busy livin’ or get busy dyin’.”

Career Roles

The role of Andy Dufresne has made Tim Robbins a household name. He was plucked for the part after such diverse work as Ron Shelton’s baseball comedy Bull Durham (1988), Adrian Lyne’s psycho-thriller Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and Robert Altman’s Hollywood satire The Player (1992). Producer Niki Marvin said Robbins possessed the sort of enigmatic quality required of Andy, and Robbins even asked to be placed in solitary confinement while he prepared for the role. (A)

“A lot of people, more than any other movie I’ve done, have come up to me about that movie,” Robbins said. “It’s not just, ‘Hey, I liked that movie. You were really good in that movie,’ it’s, ‘That movie was important to me or that’s my favorite movie of all time.'” (A)

Morgan Freeman has had a similar experience: “Everywhere I go, people who have seen it react to it fondly.” (A) Though King’s original story had Red as a white Irishman, Darabont liked Freeman so much that he changed the character to an African American. The performance earned Freeman his third Oscar nomination, after Street Smart (1987) and Driving Miss Daisy (1989), but like those prior brushes with Oscar, he left empty handed. This is likely because he was entered into the Leading Role category and had to go up against Tom Hanks’ career role as Forrest Gump.

It would be a full decade before he was nominated again, and the fourth time was the charm. Freeman won for Million Dollar Baby (2004), directed by Clint Eastwood, who had fittingly directed Robbins’ first Oscar for Mystic River (2003), where Robbins’ watery demise made me think of something he had said in Shawshank: “You know what the Mexicans say about the Pacific? They say it has no memory.”

When fans called the Oscars overdue, they were no doubt thinking of Andy and Red. And why not? By that point, Robbins already seemed so familiar, and Freeman had long ago convinced us that he was the voice of God, as we had heard his angelic voice transcend celluloid dozens of times in Shawshank alone. Surely, no script has given him better passages to deliver.

Darabont the Writer

Working on a Stephen King adaptation was a dream come true for Darabont, who started in low-budget horror as a production assistant on Hell Night (1981) and co-writer on A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987) and The Fly II (1989). He had long admired King, who was already fully entrenched in film adaptations, after hits like Carrie (1976), The Shining (1980) and Misery (1990).

Darabont would finally get a chance to work with his idol when King graciously offered to lend young film students his short stories for $1, as long as the films weren’t screened commercially and King retained the rights. Darabont impressed King so much with his adaptation of The Woman in the Room, that the two agreed to work together on a feature film based off King’s Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. (A) Turns out this side of King, the humanistic side, was just as fruitful for the screen as the horror, and Darabont was just the man to deliver it.

In addition to changing Red from an Irish man to a black man, Darabont collapsed the novella’s three wardens into one — a powerful choice in creating a Nixonian figure. (A) He also introduced a number of powerful scenes that didn’t exist in the novella — case in point, the scene where Andy locks himself in the control room and blares Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro over the prison loudspeaker. It’s the first of many moments when Darabont’s writing chops are poetically on display:

RED: I have no idea to this day what those two Italian ladies were singing about. Truth is, I don’t want to know. Some things are best left unsaid. I like to think they were singing about something so beautiful that it can’t be expressed in words and makes your heart ache because of it. I tell you, those voices soared higher and farther than anybody in a great place dares to dream. It was like some beautiful bird flapped into our drab little cage and made those walls dissolve away. And for the briefest of moments, every last man in Shawshank felt free.

RED: The first night is the toughest. No doubt about it. They march you in naked as the day you were born, skin burning and half blind from that de-lousing shit they throw on you. And when they put you in that cell, and those bars slam home, that’s when you know it’s for real. Whole life blown away in the blink of an eye. Nothing left but all the time in the world to think about it.

RED: I could see why some of the boys took him for snobby. He had a quiet way about him; a walk and a talk that just wasn’t normal around here. He strolled like a man in the park without a care or a worry in the world. Like he had on an invisible coat that would shield him from this place. Yeah, I think it would be fair to say I liked Andy from the start.

RED: And that’s how it came to pass, that on the second to last day of the job, the convict crew that tarred the plate factory roof in the spring of ’49 wound up sitting in a row at 10:00 in the morning drinking icy cold Bohemian style beer, courtesy of the hardest screw that ever walked a turn at Shawshank State Prison. … We sat and drank with the sun on our shoulders and felt like free men. Hell, we coulda been tarring the roof of one of our own houses. We were the lords of all creation. As for Andy, he spent that break hunkered in the shade, a strange little smile on his face, watching us drink his beer. You could argue he’d done it to curry favor with the guards, or make a few friends among us cons. Me, I think he did it just to feel normal again, if only for a short while.

RED: Those of us who knew him best talk about him often. I swear, the stuff he pulled. Sometimes it makes me sad, though, Andy being gone. I have to remind myself that some birds aren’t meant to be caged. Their feathers are just too bright. And when they fly away, the part of you that knows it was a sin to lock them up does rejoice. But still, the place you live in is that much more drab and empty that they’re gone. I guess I just miss my friend.

Good narration is hard to pull off without sounding cheesy and overwritten, but Darabont masters it. Film may be a director’s medium, but for anyone who appreciates good writing, Shawshank‘s script alone earns it a spot among history’s finest films. The Writers Guilds voted Shawshank the #22 Greatest Script of All Time, higher than Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, and just behind North By Northwest (1959) and It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s time we start mentioning them all in the same breath.

Aside from Darabont’s clever ability to turn a phrase, his script is a marvel for its complex characterizations. Watch how Darabont charts Andy’s growth by having him drunk as a skunk in the opening scene, then having him say, “I gave up drinking” later on. Watch how he convinces us of Byron Hadley’s evil. When someone says he’s sorry to hear Hadley’s brother died, Hadley simply responds, “I’m not. He was an asshole.” Note also the clever introduction of Brooks’ character. Andy finds a maggot in his plate of food and Brooks says, “Are you going to eat that?” When Andy hands it to him, we think Brooks will eat it, only for him to reach into his pocket and feed it to his pet bird.

Darabont also sets up clever clues that you notice on repeat viewings, making Shawshank more than just a one-time flash in the pan. When the characters discuss The Count of Monte Cristo, Darabont knows full well that the book is about a wrongly accused man and a prison break. When Red says, “To this day I have no idea what those two Italian ladies were singing about,” Darabont knows full well that they’re singing about a servant outsmarting his master. And when Red tells Andy to stop wasting his time on “shitty pipe dreams,” Darabont is foreshadowing both the “pipe” and the “shitty.”

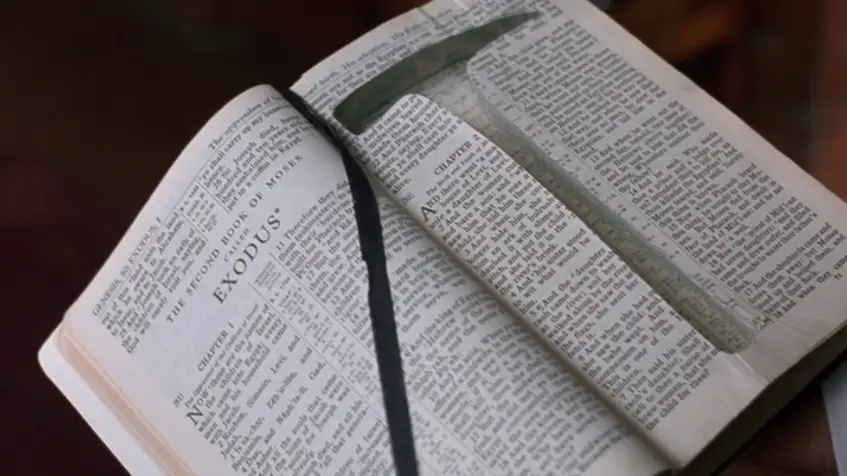

Meanwhile, take a closer look at the scene where the Warden comes into Andy’s cell and sees his Rita Hayworth poster. Darabont sets up a series of close calls that we don’t understand until after we’ve seen the movie once (i.e. the Warden discussing the poster or almost forgetting to hand Andy’s Bible back). When the Warden asks if Andy has any favorite passages, it’s fitting that Andy quotes the Book of Mark: “Watch ye therefore, for you know not when the master of the house cometh.”

Darabont the Director

With so many great set-ups and pay-offs in the screenplay, one wonders whether Darabont is a strong director or merely a great visual writer. In the academic community, the vibe appears to be the latter, that Darabont is an occasional contributor to the pop film lexicon but nothing worth in-depth academic review. The fact that he followed Shawshank with yet another Stephen King prison adaptation, The Green Mile (1999), did little to convince doubters of his range. Was he a one-trick pony, or was he beholden to his imprisoned roots, born in a refugee camp in Montbeliard, France, the son of Hungarian parents who fled Budapest during the failed Hungarian revolution?

Outside of the prison world, Darabont has seemed lost. I guess you could say he is cinematically institutionalized: Brooks in a director’s chair. The Majestic (2001) had heart and potential but never decided what kind of film it wanted to be — was it Cinema Paradiso (1988), Memento (2000) or The Front (1976)? A third attempt at Stephen King flopped with The Mist (2007) and in 2008, Darabont’s script for the fourth Indiana Jones film was rejected by George Lucas, despite Steven Spielberg saying it was the best draft since Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

Keeping all this in mind, I embarked on an analysis of Shawshank‘s directorial techniques with modest expectations, if only so my brain could compute why the film is so ignored in highbrow circles. What I found instead was a commendable directorial effort, perhaps not Jean Renoir in La Grand Illusion (1937), but just enough to surprise. No matter what else happens in Darabont’s career, he can hold his head high knowing that for a brief time in 1994, in his directorial debut, he had stepped up to the plate and delivered.

“If the one thing I’m remembered for is Shawshank, why on Earth would I complain about that?” Darabont said. “Few people are remembered for anything.” (B)

Mise-en-Scene

The aforementioned cell inspection scene also reveals Darabont’s directing chops. As Andy faces the foreground, Hadley searches the shelves over one shoulder, and Rita Hayworth hangs dangerously over the other. It’s a construction that requires a second viewing to realize, and is just one example of Darabont layering his film beyond superficial entertainment.

Symbolic Cuts

In the above scene, the Warden quotes the Gospel passage, “I am the light of the world. He that follows me shall not walk in darkness but shall have the light of life.” Note how Darabont cuts to a shot of Andy right after the words “follows me,” as if saying Andy is a Christ-like figure whose example we should follow to our own redemption.

There’s another meaningful cut later in the cafeteria scene. As Brooks talks about his pet bird Jake, saying, “I’m gonna look after him ’til he’s big enough to fly,” Darabont cuts to a shot of Andy, then to a shot of Red looking at Andy. In just two cuts, he has visually told us that Red is going to look after Andy until he, too, is big enough to leave the prison walls. After all, Andy is a “bird not meant to be caged.”

Power Reversal

Darabont also dabbles in the directorial notion of power reversal. Note the overhead shot as Byron Hadley prepares to push Andy off the factory roof. On a most basic level, the shot provides nice composition and depth of field, with the roof’s edge serving as a diagonal divider between Hadley and Andy on the roof and two men appearing miniature on the ground. On a deeper level, Darabont uses his camera to visually express the exchange of power in the scene. Watch how he cranes down to an eye-level view over Hadley’s shoulder, then dollies around to a profile “two shot,” then further around over Andy’s shoulder — all as Andy gains the power in the conversation.

Familiar Image

Shawshank also includes important motifs. Note the series of shots where the camera is positioned inside a dark space looking out:

(1) A shot that starts in darkness behind a wall as a hole is knocked through the wall to expand the prison library, bringing light into the frame. (Setup #1)

(2) A shot from inside a safe looking out as the door opens and shuts. A similar shot was previously used by Ernst Lubitsch in Ninotchka (1939). (Setup #2)

(3) Finally, a shot from inside Andy’s escape hole looking out at the bewildered Warden as he tears the poster away. (Payoff)

All three images are visually connected in familiar image. Remember, it’s Andy who brings “the light of life” into the darkness of the prison, just like the wall demolition. Meanwhile, the Warden’s safe and Andy’s escape hole both contribute to his escape and both are hidden by wall decor (by Andy’s poster and the Warden’s scripture sign). This connection makes the shots more than just a series of cool set-ups trying to put the camera in unique places. It elevates them to the level of symbolism and purpose.

Slow Disclosure

Darabont also makes effective use of slow disclosure. Watch how the opening scene unfolds by gradually giving us pieces of the puzzle — first the Ink Spots’ “If I Didn’t Care” on the radio, then a mansion, then a car, then Andy in a car, then the fact that he is disheveled, then the fact that he has a gun, then the fact that he is drunk. The order of disclosures is really important, as the effect would be totally different if, for example, we saw that he was drunk before seeing the gun. That’s visual storytelling.

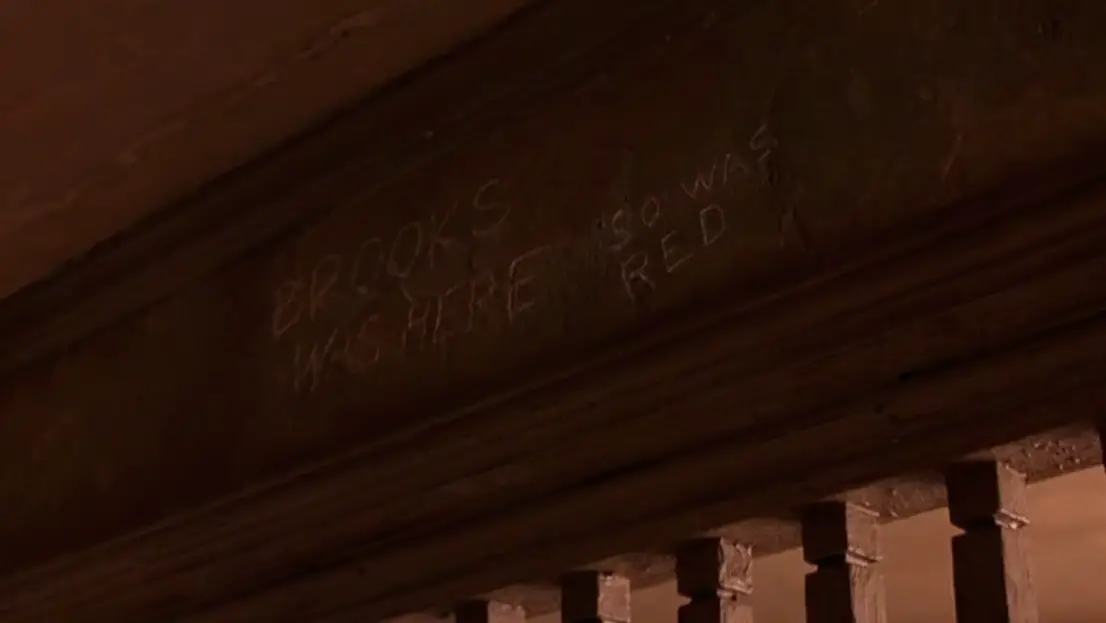

When Brooks hangs himself, note the masterful slow disclosure of the act. We first see him carving and wonder what he’s doing. We then see only his feet twitching as a table kicks out from beneath him, and his body hangs limp in a mirror to the left. Darabont then cuts to a powerful axial break that reveals what Brooks was carving, “Brooks was here,” followed by the slow disclosure of his body hanging from a piece of ceiling trim that looks awfully similar to jail bars.

Indicative Lighting

Luckily, for the sake of the film, Darabont forms a winning collaboration with cinematographer Roger Deakins. Considered one of the greatest cinematographers working today, Deakins used Shawshank to earn his first of eight Oscar nominations, including Fargo (1996) and No Country for Old Men (2007). It’s a sin this man has not yet won the gold. Expect it to happen soon.

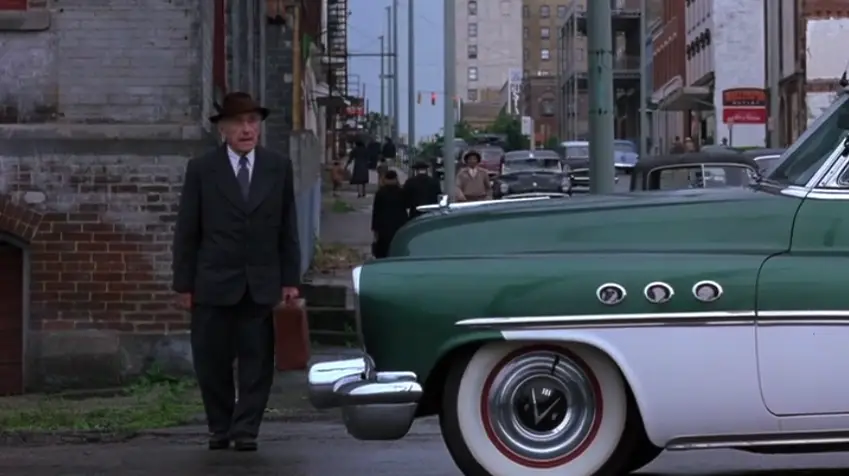

Darabont uses Deakins’ lighting for his directorial advantage. Note the shot of Brooks leaving the prison. While he’s technically a free man, Darabont composes the shot head on with the prison in the background. Brooks quite literally stands amidst the shadows of vertical jail bars around his feet. It’s a director’s way of saying this man has escaped the walls, yet has found himself in a new kind of prison — being alone in the real world.

The comparison to Red’s release is striking, as the camera now faces the outside world and there are no vertical jail bar shadows anywhere for Red to stand on.

Darabont and Deakins use a classic half-lit technique with the Warden, as the Warden speaks to Tommy in the courtyard at night. One lens of his glasses is in the light, and the other is in complete darkness, quite literally suggesting a dark side.

Later, Andy is also half-lit as he sits in his prison cell with a rope in his hands, deciding whether to get busy livin’ or get busy dyin’. Fittingly, he turns and looks into the light.

The outcome of Andy’s decision is foreshadowed through the lighting in the preceeding scene between he and Red. Andy sits on the ground, leaning against a prison wall to the right of the frame as Red enters from the left. In wide shot, the prison wall casts a diagonal shadow line that divides the frame in half. Andy sits in the shadows.

As the scene unfolds, Andy’s dialogue suggests he may kill himself, as he says, “Get busy living, or get busy dying.” However, as we cut back to the wide shot, viewers with a good eye will already know that Andy is choosing life. You’ll notice Andy walks out of the shadow side of the frame and into the light. Note that Red is left standing halfway between light and dark, as he has not yet made his choice.

Rising Above the Walls

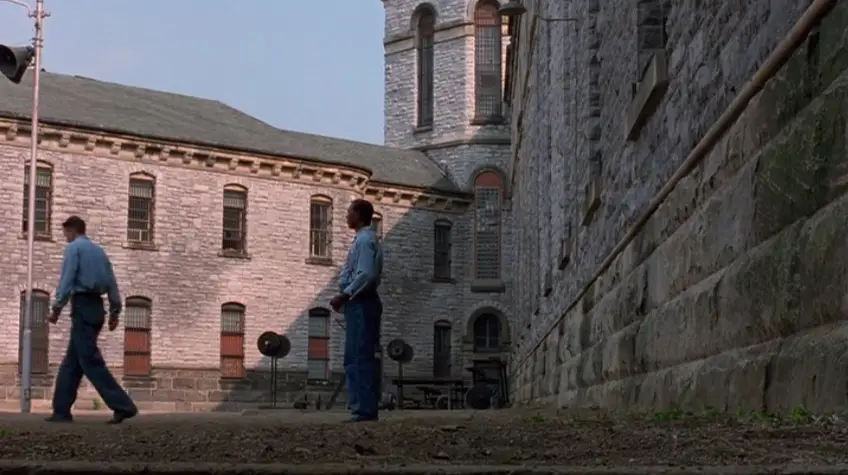

The above use of the prison wall is just one way Darabont turns his location into a thematic character itself. Darabont shot on location at Mansfield Ohio Correctional Institution, a 19th Century relic that has since been condemned for abusive practices. Sometimes the right atmosphere can add so much.

The best example comes with his brilliant low-angle POV shot as Andy enters the prison for the first time. The camera looks directly up at the towering prison above and tilts back more and more, as if one last gasp at daylight.

Having established the towering repression of these prison walls, it makes it even more uplifting when Darabont uses a sweeping camera move that soars above them. First, there’s the lyrical helicopter shot following a prison van as it turns up the driveway. The camera rises up over the prison walls and peers down into the courtyard below, before making a left turn to follow all the prisoners as they rush to a side gate where the van reappears. It’s no Touch of Evil (1958) long take, but it’s still nice.

Most famous in this regard is the aforementioned scene with Mozart over the loudspeakers. This wonderfully transcendent event encapsulates the entire theme of Andy lifting his fellow inmates beyond the prison walls. As the prison guards bang on the door, demanding he turn off the music, Andy simply smiles and turns up the volume. As the convicts stand frozen in time, looking up at the beautiful music crying out to them, the camera cranes upward in a move that rivals the battlefield shot in Gone With the Wind (1939), starting at ground level, then rising to the level of the P.A. speaker. It’s times like these that Shawshank rises from the plane where most movies sit and hovers above them with a lyrical beauty.

‘The Beauty of Music’

The most lyrical moments come when Darabont meshes these epic camera movements with the beautifully underrated score from Thomas Newman. Yes, the same Thomas Newman whose cousin Randy sang “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” for Toy Story (1995) the following year, and whose film composer father, Alfred Newman, shares the record with John Williams for the most Oscar nominations in history (45).

Newman’s Oscar-nominated theme is arguably the best in his career, though I’d have to give the edge to the The Natural (1984). When it came time to make The Green Mile, you better believe Darabont asked Newman to return. Even trailers for The Green Mile were laced with that uplifting Shawshank theme, hoping to recapture the magic once more.

Themes & Metaphors

Music itself becomes a metaphor for the film’s main theme: hope.

ANDY: It’s in here [points to head]. In here [points to heart]. That’s the beauty of music. They can’t get that from you. Haven’t you ever felt that way about music?

RED: I played a mean harmonica as a younger man. Lost interest in it, though. Didn’t make much sense in here.

ANDY: Here’s where it makes the most sense. You need it so you don’t forget.

RED: Forget?

ANDY: Forget that there are places in the world that aren’t made out of stone. That there’s something inside that they can’t get to, that they can’t touch. It’s yours.

RED: What’re you talkin’ about?

ANDY: Hope.

RED: Hope. Let me tell you something, my friend. Hope is a dangerous thing. Hope can drive a man insane. It’s got no use on the inside. You better get used to that idea.

ANDY: Like Brooks did?

The Brooks-Red connection may be the most telling theme in the entire film. It’s no coincidence that Darabont only allows those two characters to give voiceover narration, as it’s they who represent the choice to “get busy living or get busy dying.” Tied into this is the additional theme of how we each leave a mark on the world, be it the vastly differing marks carved by Brooks and Red, or the huge mark Andy leaves as he carves his own name. What’s going to be your mark? One of cowardice? Or one of hope?

If world politics is your thing, you could say Andy leaves a mark like our greatest leaders, a hard screw who comes into a cold place of corruption and uses his intense knowledge of the system to strike deals with the toughest adversaries and help the least among us.

If religion’s your thing, you could view Andy as a Christ-like figure, garnering disciples in the way of Cool Hand Luke (1967). Not only does Andy leave an overt message in his Bible (“Redemption lie within”), he also disappears from his cell in what’s described as a “miracle,” after which he dives into a cleansing body of water (baptism) and stands with outstretched arms looking toward the heavens. Meanwhile, the Warden, whether you call him a false prophet or a Bible thumper, gets his comeuppance.

Which brings us to yet another of the film’s themes: rehabilitation. If Shawshank preaches forgiveness with its religious themes, it preaches second chances with its sociological themes. Remember, these characters we love are indeed criminals. Red is an admitted murderer (“The only guilty man at Shawshank”), yet we as viewers come to see his ability to change and root for his release.

Thus Shawshank is a powerful commentary on our correctional facilities, and our obligation as a people to ensure that reformed ex-cons have a means to reenter society. Brooks’ suicide is a cautionary tale, perfectly articulated by Red:

RED: The man’s been in here 50 years, Haywood. Fifty years! That’s all he knows. In here, he’s an important man. He’s an educated man. Outside, he’s nothing. Just a used up con with arthritis in both hands. Probably couldn’t get a library card if he tried. … I’m tellin’ ya, these walls are funny. First you hate ’em, then you get used to ’em. Enough time passes, you get so you depend on ’em. That’s institutionalized. They send you here for life and that’s exactly what they take.

‘Hope is the Best of Things’

For all this, Shawshank stands as one of the most thematically rich films of all time. And it doesn’t take much to see that its most powerful theme is that of hope.

The film suggests that if you pattern your life after Andy — if you just “dig like Dufresne” — you’ll go a long way. His example is timeless: you don’t need to be flashy, just smart, with a good heart, the ambition to set an impossible goal, and the drive to work at it on a daily basis. It’s very Cal Ripken in a way.

“He realized I’m not gonna knock this hole in the wall in one week, two weeks, two months. It was gonna take a long time,” said two-time boxing Heavyweight Champion George Foreman. “He realized I’ve been put away for all this time, I’m just gonna chip at this thing every day. He worked and worked and he achieved something. He didn’t waste his time. And that’s the way it is with life. You can just work on something, work on it, you can be doing it everyday of your life, just keep doing something, and sooner or later, your life can mean something.” (D)

Shawshank recently ranked Number 23 on the AFI’s 100 Most Inspirational Films, but you could easily argue for Number 1.

“A lot of people are in prisons of relationships, of jobs they hate, of lives unfulfilled, and have given up hope,” Robbins said. “And what this movie was saying to them was it might take a while, it might take some time, but there is a light at the end of the tunnel. And if you have the patience and the belief, you can make it there.” (A)

“I’ve gotten mail and I still get mail from people who say, ‘Gosh, your movie got me through a really bad marriage or a really bad divorce, or it got me through a really bad patch in my life or a really bad illness, or it helped me hang on when a loved one died,'” Darabont said. “There’s something about the movie that helps lend some courage to people who need it.” (A)

Popular Culture

Indeed, Shawshank puts the “popular” in popular culture. Turn on the tube and you’ll see Shawshank referenced in The Nanny (1994), Reno 911 (2005), Bones (2007) and Will & Grace (2002), where Will says, “Did you give his Shawshank a redemption?”

Perhaps you’ll flip to TLC’s What Not to Wear and hear hosts Stacy London and Clinton Kelly take one look at a woman’s drab denim clothes and say, “That’s so Shawshank.” Perhaps you’ll flip to a movie channel playing Four Christmases (2008), where Vince Vaughn says his childhood was unlike Shawshank because he didn’t have an older black man showing him the ropes.

It even works when animated, as in The Simpsons, where a sign in the warden’s office reads, “His judgment cometh and that right soon,” or this spoof in Family Guy:

The film’s “poster digging” bit has been spoofed multiple times, including Muppets from Space (1999), where Rizzo digs a hole behind a sexy poster; My Name is Earl (2007), where Earl’s cellmate digs a hole behind a Dolly Parton poster; and The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning (2008), where Cheeks digs a hole in a prison wall behind a poster. I even recall an A&W Root Beer commercial using the same “Dumas-Dumbass” joke that Haywood makes in Shawshank.

Positive Word of Mouth

No one, not even Darabont, could have forseen this popularity back in 1994. Hindered by a cumbersome title and the thought of a two and a half hour prison movie, Shawshank only recouped $18 million of its $25 million budget. (A) Audiences instead flocked to Forrest Gump, Pulp Fiction and Speed.

Some vindication came when Shawshank was nominated for seven Oscars, but that faded quick when it won none. Forrest Gump reigned supreme at the Academy Awards, while Pulp Fiction garnered the most international critical attention, shattering the laws of filmmaking and winning the Palm d’Or at Cannes.

Against those two powerhouses, Shawshank would have been all but forgotten if it weren’t for the advent of VHS. Positive word of mouth led more and more people to check it out, and by 1995, it had become the single most requested video rental, doing some 320,000 units in the U.S. (A)

In this way, Darabont mimicked his idol, Frank Capra, whose masterpiece It’s a Wonderful Life had also tanked at the box office and Academy Awards, yet picked up popular steam in the years to follow. Just as Wonderful Life rode annual TV airings to classic status, Shawshank now renders TV viewers helpless to drop the remote each time it comes on cable.

The phenomenon continued to spread in pandemic fashion, to the point that in March 2006, readers of Empire magazine voted it the #1 Movie of All Time. Around the same time, IMDB users voted the film all the way to the top of the list, swapping spots with The Godfather on and off every few months.

For the public, this was it, their prized possession. But even the film’s biggest fans couldn’t help but notice a reluctance by some critics and list-makers to climb aboard.

Criticisms and Responses

In the 2002 Sight & Sound poll, not a single director or critic cast a vote for the film. The contrast between academic listology and popular listology was striking. It led to heated debate in the most private of circles, until English film critic Mark Kermode posed this question in his documentary Shawshank: The Redeeming Feature: “Tonight we attempt to answer a question that has baffled critics and academics, but to which the public seem to instinctively know the answer — just what the hell is so great about The Shawshank Redemption?” (A)

I can tell you from experience that the phrase “what the hell is so great” is a tangible sentiment out there among the academic community. A director friend of mine who studied film at the world famous FAMU in Prague said his professors despised how popular Shawshank has become. Detractors are likely to fall into one of four categories.

First, there’s the usual critical backlash against anything popular or sentimental. Something in their gut says that if the masses love it, there must be a flaw.

Second, the film is so effective in entertaining that it feels like it must be superficial, when upon closer inspection, moments of brilliance are everywhere. As Roger Ebert writes, the film “absorbs us and takes away the awareness that we are watching a film. Watching the film again, I admired it even more than the first time I saw it.”

Third, the film lacks originality in some of its story elements. Andy is but a recycled version of Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke (1967) or Jack Nicholson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975); his time in the hole a knock-off of Alec Guiness in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Steve McQueen in The Great Escape (1963); his pockets-full-of-dirt trick borrowed from The Great Escape; the bonding over outdoor tarring detail from Cool Hand Luke; the gift of a harmonica from The Grand Illusion (1937); the character of Brooks Hadlin from Birdman of Alcatraz (1962); the “only guilty man” conversation from Down By Law (1986); the Tommy test score/death subplot from Boyz n the Hood (1991); and Andy’s use of The Bible is clearly a page out of Eastwood’s book in Escape from Alcatraz (1979).

It’s hard to tell which of these are rip-offs and which are homages. It’s clear Darabont knows his history of the great prison films that came before. I’ll cut him some slack, because he at least ties these homages together with his own talent for fresh metaphors. As the late Sydney Pollack said, “[In] The Shawshank Redemption, the metaphors, if you will, were chosen with such a rare degree of originality and theatricality.”

Finally, experts turn their noses at the film’s ending, where Darabont borders on killing a home-run twist by tacking on an unnecessary beachfront finale. The movie should have ended with the bus pulling away into the distance, as Red says, “A free man at the start of a long journey, whose conclusion is uncertain. I hope I can make it across the border. I hope to see my friend and shake his hand. I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams. I hope.”

At this point, Red has made his decision to “get busy living.” He’s found his redemption and even says the “conclusion is uncertain.” The story’s over. We don’t need to see him embrace Andy on the beach. Leave that moment to the viewer’s imagination. Contrary to what some think, we as viewers don’t have to be shown everything. More films should give the viewing public more credit.

Darabont agreed, as this is where he originally wanted the film to end. It was the suits at Castle Rock who forced him to reconsider, saying that after all this despair, Darabont owed the audience the satisfaction of seeing the two friends reunite.

Maybe they’re right. Maybe Shawshank‘s huge following would never have taken hold with a more ambiguous ending. Maybe it needs the beach scene like It’s a Wonderful Life needs “Auld Lang Syne” after spending two-and-a-half hours beating down its protagonist. Either way, it may be the chief reason why Shawshank struggles on academic best lists. When directors spoon-feed, critics view it as pandering. Which is why Darabont should release a Director’s Cut, axing the beach scene and leaving us with the poetry of his words, read in Morgan Freeman’s angelic voice over the cleansing Pacific blue.

Legacy

Until then, some may continue to find fault with Shawshank. I happen to believe the film’s strengths far outnumber its flaws, and more and more critics are warming up to the idea. Tim Dirks of AMC’s Filmsite was one of the first, placing Shawshank in his Top 300. Roger Ebert followed, adding it to his “Great Films” registry in 1999 after leaving it out of his Top 10 movies of 1994. (C) Crazy how a film can be unworthy to be in the conversation of a single year’s best films, then five years later, it’s included in a list of the greatest films of all time.

The biggest development in this regard came in 2007, when the American Film Institute reconstructed its Top 100 list for a 10th Anniversary special. After missing the original list in 1997, The Shawshank Redemption finally made the cut at #72 for the 10th Anniversary, higher than both Forrest Gump and Pulp Fiction, mind you. As Morgan Freeman hosted the CBS special, he beamed with pride: “There is no magic formula for excellence. But you try. And you hope that a film you are a part of will be one that stands the test of time. So you can imagine my pride.”

If listology is at least part democracy, you’ll likely see The Shawshank Redemption inch its way up more and more best lists. All fans need to do is keep up the pressure and, over time, they’ll have their wish. That’s all it takes sometimes: pressure and time. That and a big god-damned poster.

Citations:

CITE A: Shawshank: The Redeeming Feature, Special Edition DVD special feature

CITE B: Darabont’s IMDB Bio

CITE C: http://www.innermind.com/misc/s_e_top.htm

CITE D: AFI’s 100 Cheers