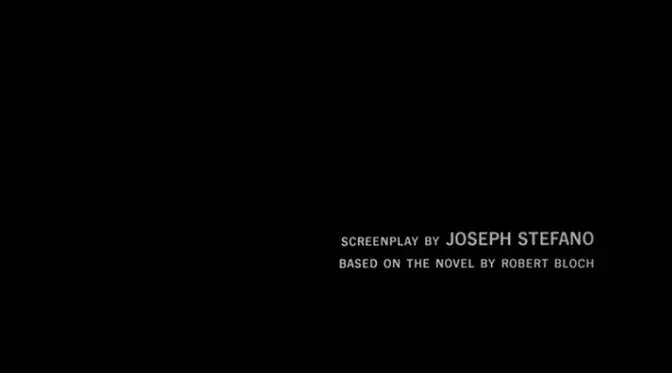

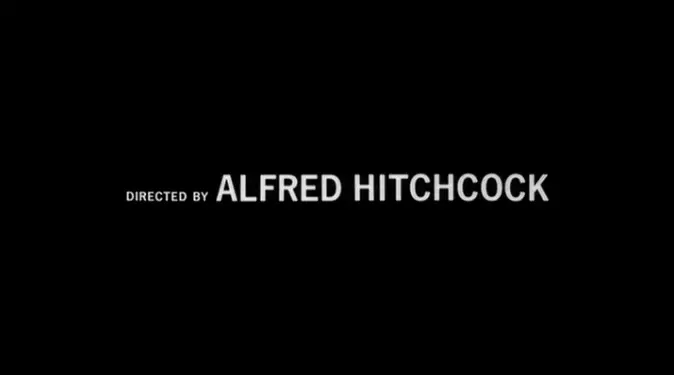

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Producer: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Robert Bloch (book), Joseph Stefano (screenplay)

Photography: John L. Russell

Music: Bernard Herrmann

Cast: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, John McIntire, Simon Oakland, Frank Albertson, Patricia Hitchcock, Vaughn Taylor, Lurene Tuttle, John Anderson

![]()

Introduction

If you live long enough, you hope to have that rare experience of sitting in a theater when a movie comes along that changes everything. This may happen once or twice in a lifetime, if you’re lucky. After all, you never know when such a zeitgeist is going to strike. So wouldn’t I give anything to have been sitting there during that initial screening of Psycho. To stand in the long lines outside New York’s Radio City Music Hall, anticipating the new film from Hollywood’s most famous director and one of television’s most famous personalities. To see advertisements of Alfred Hitchcock forbidding us to arrive after the film’s start (a historical first), locking the doors after the projector rolled, and begging us not to share the film’s secret afterwards (a virtual impossibility in today’s internet age).

What I wouldn’t give to have been sitting there, watching one of Hollywood’s leading ladies, Janet Leigh, step into that shower. To share in her naivety as to how culturally significant that shower was about to become. To hold my breath as a shadowy figure approached that shower curtain. And to scream as those shower rings ripped open and a knife blade chopped to Bernard Herrmann’s screeching strings!

“I’ve never heard such screaming — sustained screaming — from the audience,” said critic/director Peter Bogdanovich, who was covering the event for Esquire at the time. “You couldn’t hear the soundtrack. It was unprecedented, and it really was the first time that going to the movies was not a safe experience.” (A)

The brutal murder that ensued remains the most documented, most imitated and most recognized murder in movie history. Forget spoilers. Even those who haven’t seen Psycho already know Leigh’s fate. Everyone and their mother (pun intended) knows the shower scene and that a boy’s best friend is his mother. The key question today is not how to conceal the film’s surprise, but how a single moment could become so etched into our collective minds — even those who have not seen the movie? I search and search for the answer and can only come to one word: Hitchcock.![]()

Plot Summary

While the film could have began at the Bates Motel with an in-your-face killing in the first 10 minutes — like Jaws (1975) or Scream (1996) — we instead start with the bosomy blonde Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) having a hotel room affair with a married man, Sam Loomis (John Gavin), during her lunch break in Phoenix, Arizona. Upon returning to work, she decides to steal $40,000 from her employer and take off down the road to run off with her lover.

The money becomes perhaps Hitchcock’s greatest MacGuffin — his made-up term for a plot device that consumes the characters, but which is really a red herring to the key themes in question. And so, we follow Crane’s car trade-ins and run-ins with the cops, until one rainy night, she pulls off the highway and sees the neon lights of the Bates Motel.

SPOILERS: The scrawny Motel operator Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) comes running from the adjacent Bates House and offers her a room in Cabin No. 1. After sharing sandwiches with Norman in the hotel parlor, Marion comes to her senses and decides she’ll return the stolen money the next morning. She hops in the shower to wash away her sins and get ready for bed, but is suddenly sliced and diced by a shadowy female figure, presumably Norman’s controlling mother Mrs. Bates.

As Norman cleans up the mess and sinks Marion’s car in the river, we presume he is a dutiful son protecting his murderous mother. But before long, Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles) and lover Sam Loomis (John Gavin) come looking for her, along with a suspicious detective named Arbogast (Martin Balsam). In the end, they discover the shocking truth: that Norman suffers from split personality disorder, dressing up as his mother to commit murder every time he becomes aroused by a woman.

![]()

Leigh & Perkins

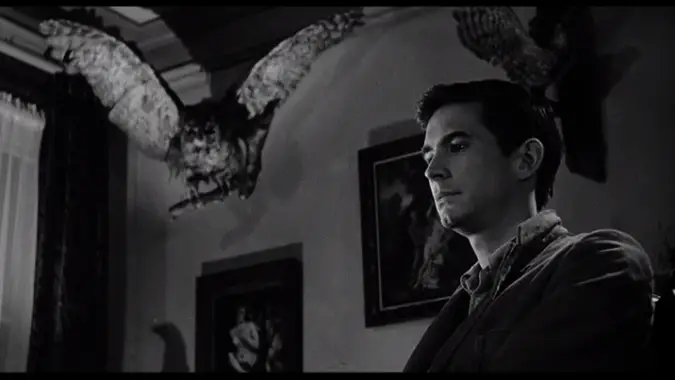

The complex, multiple-personality role required the finest of actors, and Anthony Perkins was the right person for the right time in movie history. It was the role he was born to play, and yet the one he never escaped, typecast simply to three Psycho sequels.

While this may have caused Perkins frustration in his career, he will forever be a screen legend. The AFI voted Norman Bates the No. 2 Greatest Villain of All Time, behind only Hannibal Lecter and ahead of Darth Vader and The Wicked Witch of the West. Perkins commands the character, stuttering his way through alibis and chewing like one of his symbolic stuffed birds in Hitchcock’s low angle:

Perhaps it worked so well because Perkins was so unassuming. He was not a massive, intimidating character, but rather a thin, awkward man. He possessed a certain charm that was at times endearing and other times mysterious, best on display as Marion and Norman share sandwiches. He at first seems gentle, making small talk about hobbies, but with one mention of his mom, he becomes offended:

“There’s a moment in that scene where you can see the menace taking hold, and then he puts it right back,” Janet Leigh told the AFI, praising her co-star. “That to me was terrifying.”

Leigh deserves immense credit herself, earning the sole Oscar nomination of her career. The wife of Tony Curtis (Some Like it Hot) and future mother of Jamie Lee Curtis (Halloween), Leigh was a huge star at the time, cast alongside Liz Taylor and Mary Astor in Little Women (1949), playing across Jimmy Stewart in The Naked Spur (1953) and assaulted in a motel room in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). In Psycho, her best acting comes during her getaway with the stolen money, the corners of her mouth slowly forming a devilish smile as she imagines her co-workers’ reaction in voiceover.

It was precisely this starpower that allowed for the shock to play so well. After all, Hitchcock couldn’t kill off an A-list star as big as Janet Leigh in the first 48 minutes, could he? Did that just happen? Who do we confide in now? Where is this thing going? The answer lies in one simple fact: it’s not her story; it’s Norman’s. Our sympathies are transferred so effectively that when Norman tries to sink Marion’s body in the trunk of his car, we gasp as the car stops, half-submerged. Will he be caught? The minute we ask ourselves that question, Hitchcock has swapped out sympathies from Marion to Norman.

It was precisely this starpower that allowed for the shock to play so well. After all, Hitchcock couldn’t kill off an A-list star as big as Janet Leigh in the first 48 minutes, could he? Did that just happen? Who do we confide in now? Where is this thing going? The answer lies in one simple fact: it’s not her story; it’s Norman’s. Our sympathies are transferred so effectively that when Norman tries to sink Marion’s body in the trunk of his car, we gasp as the car stops, half-submerged. Will he be caught? The minute we ask ourselves that question, Hitchcock has swapped out sympathies from Marion to Norman.

![]()

Screenplay

The twisted tale was the brainchild of author Robert Bloch, who penned the 1959 novel, based on real-life Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein.

“I discovered, much to my surprise, that I could become a psychopath quite easily,” Bloch said.” I could think like one and I could devise a manner of unfortunate occurrences. So I probably gave up a flourishing, lucrative career as a mass murderer.” (B)

Bloch had discovered that the line between mental stability and psychopathy is very thin, captured it the classic line: “We all go a little mad sometimes.” It is this idea that eats at viewers. Anyone around us could be a psychopath. Any night you could stop at your own Bates Motel.

It was then the job of Joseph Stefano to adapt the screenplay, writing one of the WGA’s Top 101 Screenplays of All Time. The script’s dialogue is fantastic, including the AFI’s No. 56 Greatest Movie Quote: “A boy’s best friend is his mother.” What makes the line great is the fact that it carries a different meaning between first and second viewing. On first watch, it paints Norman as the ultimate mamma’s boy. On the second watch, we realize Norman is indeed talking about his alter-ego.

“It was the original Sixth Sense,” Steven Spielberg told the AFI, praising Psycho for so masterfully concealing its final twist.

Hitchcock immediately bought the rights to the novel and bought as many copies as possible at bookstores around Hollywood to contain the story’s secrets. He also held fake casting sessions for the part of Mrs. Bates and kept a chair with her name on it during production photos of the set, just so Hollywood insiders would think her character was an actual part.

If there’s one flaw in the script, it’s the tacked-on finale with a psychiatrist’s overly dramatic explanation of Norman’s condition. Today, it feels like unnecessary audience hand-holding. Perhaps this is because we’re now fully aware of the concept of mental illness. But in 1960, it may have been necessary for audiences to understand Norman’s split personality — and walk away satisfied. Either way, there’s no denying it sets up the great final appearance from Norman, now completely converted to Mrs. Bates, smiling up at the camera and saying, “He wouldn’t even harm a fly.”

![]()

Hitchcock’s Master Class in Directing

A film theory student once asked me, “Aren’t we giving Hitchcock too much credit? Doesn’t most of the credit for that awesome twist belong to the writer?” This student highly underestimates the power of the director. Sure, the script is the foundation of any great movie. Without it, we have nothing. But viewers should realize that you could give the same script to 12 different directors and get 12 different moves. The final viewing experience hinges on the director’s interpretation of the script through his own directorial vision. The reason Psycho goes down in history is because its clever script and powerful performances are visually interpreted by history’s greatest filmmaker, Alfred Hitchcock.

Slow Disclosure

In the great tradition of Orson Welles’ slow disclosure of Xanadu in the opening of Citizen Kane (1941), Hitchcock provides a brilliant opening helicopter shot — something he would repeat later in Frenzy (1972). The shot begins in an extreme wideshot of the Phoenix skyline, then moves closer and closer to a hotel window with a series of dissolves. Eventually, the camera appears to move “through” the window in a brilliant filmmaking trick — just like Kane — dissolving from an exterior shot of the window sill to an interior shot that reveals the bedroom where Janet Leigh is having an affair with Sam Loomis.

The Male Gaze

The move through the private hotel room is just the first of many instances where Psycho continues Hitchcock’s career-long obsession with voyeurism, which feminist film theorists have dubbed The Male Gaze. In fact, it is the last in a loose voyeuristic trilogy with Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958).

The most jarring example of The Male Gaze may be a low-angle close-up of a cop wearing sunglasses. This was no doubt the inspiration for the sunglass-wearing prison guard in Cool Hand Luke (1967).

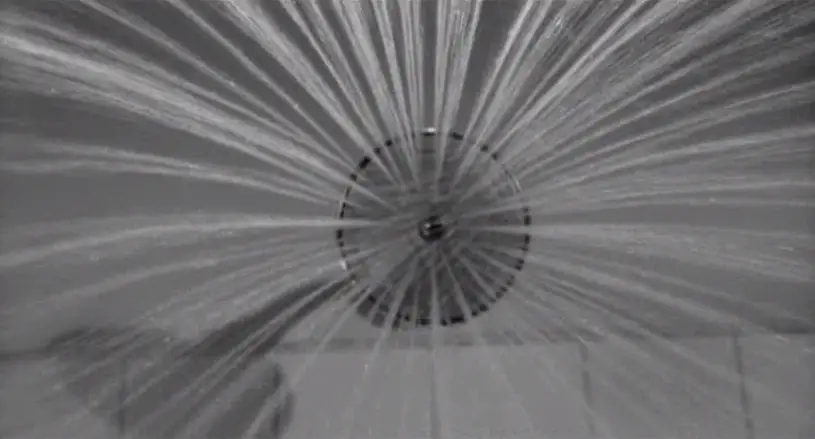

When Marion climbs into the shower for her fateful final cleanse, Hitchcock repeatedly shows the shower head above her like a watchful eye.

When Marion climbs into the shower for her fateful final cleanse, Hitchcock repeatedly shows the shower head above her like a watchful eye.

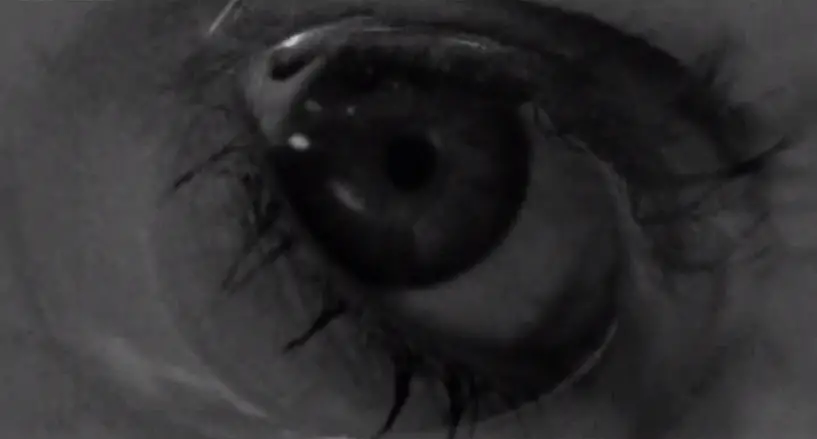

The shower drain also becomes an eye, dissolving from the drain into Marion’s lifeless eye.

The shower drain also becomes an eye, dissolving from the drain into Marion’s lifeless eye.

Despite all of this, the most obvious example of The Male Gaze comes soon after as Norman Bates removes a picture frame in his parlor to reveal a self-made pervert’s peephole. As he gazes into the peephole, we cut to his POV as he watches Marion get undressed. The shift from objective camera (normal) to subjective camera (POV) not only places us inside Norman’s perspective, it also asks a tough question of ourselves — are we complicit in watching this beautiful woman get undressed?

Adding to this “invasion of privacy” is the film’s place as the first movie to feature a flushing toilet. You’ll notice that Norman can’t bring himself to say the word “bathroom” when he’s introducing the room to Marion, because he knows he’ll be watching it through his peephole. After Marion’s murder, Norman gazes at the bathroom bloodshed and knocks a picture frame off the wall. It’s a callback to the very masturbatory perversion that caused her murder in the first place. In fact, Hitchcock went around set referring to Anthony Perkins as “Master Bates.” (C)

Murderous Multi-Angularity

When we’re not slowly watching perverted POV shots, Hitchcock also demonstrates a mastery of quick-cutting montage through multiangularity. This, of course, comes during the film’s most famous scene — and perhaps the most famous scene in all of film — the shower murder.

I beg you to watch the scene in slow motion, noting each cut from various angles. The knife never actually punctures the body; the stabs are an illusion in your mind, where the scariest movies always happen. After this, rewatch the scene at normal speed and see how all the shots fit together to create “controlled chaos,” painstakingly storyboarded by Hitchcock and masterfully edited by George Tomasini. The shot sequence has been emulated by countless filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese, who used it as a model for Sugar Ray’s final pummeling of Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull (1980).

Personified Camera

Hitchcock also makes effective use of personified camera, where the eye of the camera becomes an active participant in the action, independent of the characters on screen. An early example comes moments before Marion decides to steal the money. As Marion gets dressed in her hotel room, the camera slowly pushes in on the money envelope.

Later, he uses it again just moments after Marion’s death. As her lifeless body lies on the bathroom floor, Hitchcock’s camera floats from her motionless eye, to money envelope wrapped in the newspaper, then out to the window, where we see Norman emerge from the Bates House in a panic.

Symbolic Wardrobe

Just because the film was a return to black-and-white (Rebecca, Shadow of a Doubt) after years of Technicolor (Vertigo, North By Northwest) didn’t make Hitchcock any less symbolic with his costume colors. After all, in Notorious (1946), he had Ingrid Bergman shift from black-and-white stripes (moral ambiguity) to solid colors (pure morality).

In Psycho, he once again employs legendary costume designer Edith Head (Rear Window, Vertigo) to express Marion’s morality through color contrast. At the start of the film, before her money theft, she is dressed in the purity of white lingerie. But the moment she steals the money and shifts to the dark side, she wears black lingerie. She continues to wear this black lingerie as Norman watches her through the peephole, but loses it after she decides to return the money. Unfortunately by this point, her fate is sealed.

Mise-en-Scene

Psycho also features glorious use of mise-en-scene, a fancy French term for all of the visual elements in the frame used to infer meaning. Hitchcock famously uses this concept in the parlor scene, where Marion and Norman talk over sandwiches.

The background features a series of stuffed taxidermy birds. Not only are they “birds of prey,” they are visual clues as to what happened to Mrs. Bates: her corpse preserved like one of the stuffed birds. After all, the term “bird” was a slang term for women at the time (a theme repeated in Hitchcock’s next film, The Birds).

You’ll also notice that Leigh’s character is named “Marion Crane,” like the bird. What’s more, Norman’s license plate reads “NFB,” standing for Norman F. Bates. The novel Psycho reveals that the “F” stands for his middle name, Francis, as in St. Francis, the patron saint of birds! (D) You see, every detail of this movie is thought out. What do you think Hitchcock meant by the “ANL” on Marion’s license plate? Hitchcock truly was a dirty bird.

Split Personality: Graphics, Shadows & Reflections

Perhaps the most rewarding technique on repeat viewing is the symbolic foreshadowing of Norman’s split personality. This is apparent right from the opening credits, as legendary title designer Saul Bass employs a “split font” technique to hint at Norman’s split identity. Most directors think of opening credits as a throwaway necessity, or scrap them entirely. But Hitchcock, a true master, used them to foreshadow his twist for any viewer smart enough to be on the lookout.

Norman’s dual persona is also foreshadowed in window reflections. Note Norman’s reflection as he apologizes to Marion after a shouting match with his “mother.” “I’m sorry,” he says. “My mother isn’t quite herself today.” This is the perfect blend of directing and dialogue, similar to Arbogast asking Bates, “Would you mind looking at the picture before committing yourself?” He means “committing yourself” to the alibi, but really Hitchcock is foreshadowing Norman being committed to the mental home in the end.

Norman’s dual nature is also expressed through lighting, particular his half-lit face as he watches Marion’s car sink in the river.

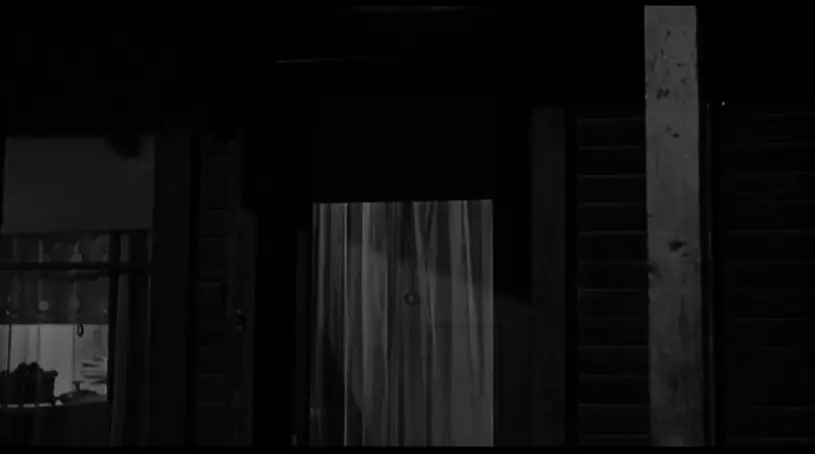

Light and shadow also creates an effective silhouette of “Mrs. Bates” in the window of the Bates House when Marion first arrives. This, of course, is Norman walking around in his mother’s clothes, but the silhouette removes all detail of identity. Hitchcock uses a similar technique in Vertigo (1958), as Kim Novak appears in the window of the Empire Hotel, and later appears in silhouette against neon green light from the window.

Light and shadow also creates an effective silhouette of “Mrs. Bates” in the window of the Bates House when Marion first arrives. This, of course, is Norman walking around in his mother’s clothes, but the silhouette removes all detail of identity. Hitchcock uses a similar technique in Vertigo (1958), as Kim Novak appears in the window of the Empire Hotel, and later appears in silhouette against neon green light from the window.

Still, my favorite Psycho shadow is that of a guillotine outside the Bates Motel office after Marion’s murder. This is no film theory wishful thinking here. The guillotine blade appears absolutely intentional, as Hitchcock’s camera lingers outside the door as Norman turns off a series of lights inside. (D)

If you doubt Norman’s doorways as symbolic passageways of death, watch closely as he carries Marion’s body out to his car. As AMC Filmsite’s Tim Dirks brilliantly points out, Norman wraps Marion’s body in the shower curtain — just as Marion had wrapped the money in the newspaper — and carries her out the door across the threshold like a pair of newlyweds. (D) If you doubt Hitch’s place as a “master of the macabre,” look no further than Norman Bates carrying his corpse bride.

Cross-Tracking

While the guillotines and mirror reflections are more amusing touches, a more immediately effective technique is Hitchcock’s cross-tracking. The technique uses repeated cuts back and forth between two specific tracking shots: (a) a back-tracking dolly that faces the character, and (b) a forward-moving POV shot from the character’s perspective. Hitchcock makes masterful use of this as both Lila and Arbogast approach the Bates House.

Falling Camera

Once we’re inside the house, Hitchcock plays our emotions brilliantly. I received all the proof I needed in the Summer of 2012, when the National Mall showed Psycho for its annual “Screen on the Green” series in front of the U.S. Capitol building. I watched the millennial audience out of the corner of my eye, as Arbogast climbed those stairs, Mrs. Bates slowly opened the door, painting a sliver of light across the floor, and Hitchcock cut to that high-angle, knowing what was about to happen. Sure enough, as the knife-wielding “mother” tore across the screen to Bernard Herrmann’s strings, the audience screamed their butts off. It still works after all these years.

Then, something odd happened. After Arbogast was sliced in the face and began his backward tumble down the stairs, the audience snickered. This is because of a technique Hitchcock tried, strapping Martin Balsam to a harness and pulling him down the stairs with the camera right above his face. Today, after being desensitized to many a bloody horror flick, the Arbogast “falling technique” admittedly feels odd. It’s more of an artful ballet of murder than a realistic depiction. Perhaps all these years later, Hitchcock has been proven right in his assertion that Psycho “belongs to filmmakers.” (E)

![]()

Masterful Music

For all of Hitchcock’s directing genius, Psycho may never have become a classic if not for one crucial element: Bernard Herrmann’s score.

Herrmann’s career is unrivaled in movie history, debuting with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane (1941), then bringing us The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North By Northwest (1959), TV’s The Twilight Zone (1959), Psycho (1960), and Cape Fear (1962), before ending with Martin Scorsese on Taxi Driver (1976).

Of all of these, Psycho is easily his most famous and most acclaimed, ranking No. 4 on the AFI’s Top 25 Movie Scores of All Time, behind only Star Wars (1977), Gone With the Wind (1939) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). The score borrows slightly from Beethoven’s “Eroica” and features one track after another of the best suspense music that movies have to offer: “Prelude,” “The City,” “Flight,” “Temptation” and “The Parlor.”

Of course, the entire thing wouldn’t have been complete without the slashing strings of “The Murder,” used first during the shower scene. As the violins slash, it sounds as though the music may cut we the viewers. Even folks who have never seen the film know this particular piece of music and immediately associate it with a stabbing. That is the testament to a great score.

![]()

Pop Culture

As the 1960s slipped into the 1970s, Hitchcock found many admirers who instantly paid homage in their own films. The most overt was perhaps Brian DePalma, who ripped Rear Window (1954) for Sisters (1973) and Vertigo (1958) for Obsession (1976). But it was his horror masterpiece Carrie (1976) that referenced Psycho, naming Carrie’s high school Bates High School after Norman Bates and lifting Hermann’s slashing violin score to denote Carrie’s use of her telekinetic powers.

The film also left is influence on many a “slasher film,” most notably John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), which starred Janet Leigh’s daughter (Jamie Lee Curtis, a combination of her parents Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis) and borrowed several Hitchcock character names for its own character names: Loomis (Psycho) and Doyle (Rear Window).

As the slasher genre reached its zenith in the ’80s and ’90s, Anthony Perkins returned for three belated feature film sequels: Psycho II (1983), Psycho III (1986) and Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990), as well as a made-for-TV movie called Bates Motel (1987). If you ever doubt Hitchcock’s importance to Psycho‘s success, just watch the spinoffs where his touch was nowhere to be found.

Horror buffs will tell you that Psycho is in part based on the real life Wisconsin murders of Ed Gein. And as the Gein-Bates connection grew in movie lore, other filmmakers revived Gein’s story for their own horrific creations: Tobe Hooper in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Jonathan Demme in The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

But it’s not just horror that references Psycho. In Mrs. Doubtfire (1993), Robin Williams turns and looks at himself in women’s clothing and gasps, “Ahh, Norman Bates!”

The biggest reference came in 1998, when director Gus Van Sant decided to remake Psycho as his much-anticipated follow-up to Good Will Hunting (1997). The remake, starring Anne Heche, Julianne Moore, William H. Macy and Vince Vaughn as Norman Bates, advertised itself as a shot-for-shot remake. But it wasn’t.

The motel thriller Identity (2003) was a copycat movie with more motel room murders, important room keys and a split-personality conclusion.

At the turn of the millennium, Psycho became famous to the internet generation in the infamous YouTube video “Star Wars Kid,” where Norman Bates peers through his peephole to see an overweight kid flailing around with a light sabre.

While the year 2012 didn’t bring an end to the world, as the Mayans predicted, it did bring a feature film called Hitchcock (2012), starring Anthony Hopkins as Mr. Hitch himself in a plot that followed the “making of” Psycho. How many movies can claim to inspire other movies — purely about the making of them?

Even more recently, A&E launched the original TV series Bates Motel (2013), telling the prequel backstory of Norman with his mother, Norma (Vera Farminga), albeit in a modern-day setting.

Perhaps more important than any single movie reference, is the fact that the Bates Motel has become one of the most famous sets in Hollywood history. The one-story motel and accompanying house is visited to this day at Universal Studios Hollywood, but none of these visitors had it in for them quite like Marion Crane.

![]()

Listology Legacy

With so many pop culture references, Psycho‘s legacy is safe. But where does it stand among the kingmakers of the listology world?

For decades, Psycho was Hitchcock’s lead representative on most movie best lists. But in recent years, Vertigo has surpassed it. In 2012, the Sight & Sound international critics poll ranked Vertigo the single greatest movie of all time, while ranking Psycho in a tie at No. 35. I dare you to name another “slasher flick” that will ever top Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Here in America, on the AFI’s Top 100 list, Psycho ranked No. 14 all time, while Vertigo ranked No. 9. However, when broken down by genre, Psycho topped the AFI’s 100 Thrills list, ahead of legendary achievements like Jaws (1975) and The Exorcist (1973).

But the film isn’t just a powerhouse on art-house best lists. It also dominates mainstream voter polls. You’ll note that Psycho carries a powerful 8.6 rating on IMDB, tied for Rear Window as Hitchcock’s highest rating on the site. This is the kind of cross-over appeal that The Film Spectrum is all about.

While Vertigo is my own personal favorite, no Hitchcock film better walked the line of art-house masterpiece and mainstream rollercoaster than Psycho. It may very well be the greatest marriage of cinesthetic visionary and popcorn thrill-seeker in all of cinema. And if that’s the case, can you really argue that Psycho isn’t the greatest horror movie of all time? It’s hard to imagine a movie that will ever change horror history the way the Master of Suspense did when he invited us into his male gaze, shifted our sympathies, challenged our complicities and left us afraid to ever shower again.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Peter Bogdanovich, The Times of London

CITE B: Faces of Fear, by Douglas E. Winter (1990)

CITE C: IMDB Trivia

CITE D: Tim Dirks, AMC Filmsite

CITE E: Roger Ebert’s “Great Movies”