Director: John G. Avildsen

Writer: Sylvester Stallone (screenplay)

Producer: Robert Chartoff, Irwin Winkler (Charthoff-Winkler)

Photography: James Crabe

Music: Bill Conti

Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Talia Shire, Burt Young, Burgess Meredith, Carl Weathers, Thayer David, Joe Spinell, Jimmy Gambina, Bill Baldwin Sr., Al Silvani, George Memmoli, Jodi Letizia, Diana Lewis, George O’Hanlon, Larry Carroll

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- The Real Rocky

- Sly & His Script

- Supporting Cast

- Avildsen’s Directing Upset

- Cut Me Mick: Art of Montage

- Room to Breathe

- Reflections and Push-Ins

- Escaping the Cage

- Pioneering the Steadicam

- Soundtrack

- The Sequels

- Pop Culture

- Legacy & Inspiration

Introduction

Why love Rocky? “I’ll tell you why. ‘Cause I’m sentimental. And a lot of other people in this country are just as sentimental. And there’s nothing they’d like better than to see Apollo Creed give a local Philadelphia boy a shot at the greatest title in the world on this country’s biggest birthday.”

To argue the merits of Rocky as a popular phenomenon seems almost unnecessary, and any plot summary is merely a formality. Everyone and his mother knows the story of Philadelphia down-and-outer Rocky Balboa and his miracle long-shot at boxing’s heavyweight crown. Few films can claim to have been seen, and beloved, by so many. Even those who haven’t seen the film feel as if they have, and everyone, fans and non-fans alike, can instantly call to mind the film’s characters, quotes, music and images. It’s a part of the American experience, an inspiration to millions and the blueprint for so many sports movies to follow.

Unfortunately, the film has become so diluted by pop culture references and endless sequels that watching it today almost feels like an exercise in self-parody. It’s so easy to forget that Rocky, the original, is actually a solid film, however calculated. It’s the source of all our subconscious training montages, an accessible commentary on the working class, the romanticized epitome of the American Dream, a record setter at the box office, the Best Picture of 1976, one of the finest love stories in movie history and the greatest underdog story ever told.

Plot Summary

Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone) is a Philadelphia southpaw nicknamed The Italian Stallion, well past his prime and now brawling for peanuts in converted churches, where he bums cigarettes off fans who call him a bum. As the gym’s owner, Mickey (Burgess Meredith) says, “You’ve got heart kid, but you fight like a goddamned ape. The only thing special about you is that you’ve never had your nose broken.”

Outside the ring, Rocky struts the urban streets in a ratty black hat, bouncing a rubber ball and collecting debts for a local waterfront racketeer, Tony Gazzo (Joe Spinell). But coming back to his crummy apartment and using his bare hand to apply ice to his bruised forehead, he realizes how much he hates his existence. Things only get worse when he walks into the gym and finds his gear has been moved out of his locker and placed in a bag on “skid row” to make room for a younger prospect. A furious Rocky confronts Mick, who tells him the cold, hard truth: “You had the talent to become a good fighter, and instead of that, you became a leg breaker, some cheap, second-rate loan shark!” When Rocky responds, “It’s a livin’,” Mickey retorts, “It’s a waste of life.”

Indeed, Rocky’s life has bottomed out such that even the neighborhood kids mock him with chants like, “Screw you, creepo.” It seems Rocky has just one thing left in his life — the hope that he will one day win the heart of mousy pet shop clerk, Adrian (Talia Shire). She’s the introverted sister of his friend Paulie (Burt Young), a drunken meat packer, who doesn’t want to see his sister become an old maid. Everyday, Rocky stops by the pet shop and cracks a terrible joke in attempt to woo Adrian, made shy after years of being told she is ugly and a loser. Finally, with the unintended help from the loud-mouthed Paulie, Rocky at long last wins a date with Adrian. He combats her shyness (“But it’s Thanksgiving”) with the fact that he has nothing to lose (“Yeah, to you. To me, it’s Thursday”). Their date at a local ice rink is a hit, and Rocky has found a soulmate. “I think we make a real sharp couple of coconuts,” he says. “I’m dumb and you’re shy.”

Things finally seem to be going Rocky’s way, yet his biggest break is still on the horizon. Heavyweight champ Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers), the film’s proxy for Muhammed Ali, is pissed that his opponent for a much-hyped bicentennial match has pulled out with a last-minute injury. The publicity has already been done, and unless Apollo wants to eat the cost, he’ll have to find a replacement. Enter the champ’s own ingenuity, pitching a novelty event where he will offer a once-in-a-lifetime title shot to an unranked contender, which turns out to be Rocky. To offer such a shot at the American Dream to an Italian, the nationality that discovered America, and host it in Philadelphia on the nation’s 200th birthday, would be proof that America is truly the land of opportunity. Creed chuckles at his own salesmanship: “Apollo Creed vs. The Italian Stallion. Sounds like a damn monster movie.”

Instantly, everyone in Rocky’s life wants to jump on the bandwagon, seeing Rocky as their own meal ticket to success. Paulie lets Rocky train in his meat locker in exchange for slapping an advertisement on his boxing robe. The bizarre ritual of pounding raw meat becomes a sensation on local TV.

Yet the real training is left up to Mickey, who has to eat crow and apologize for all the years he’s forgotten about Rocky. We understand Rocky’s initial resistance, but approve when he finally sets his pride aside and lets Mickey be his manager. The two are meant for each other — Mickey’s expertise is Rocky’s only chance at hanging with Creed, and Rocky is Mickey’s last best hope at boxing glory.

The hungry underdog Rocky out-trains the cocky veteran Creed, and when they come out swinging, Creed is so surprised that his trainer says, “He doesn’t know it’s a show, he thinks it’s a damn fight!” The ensuing battle is epic, breaking Rocky’s nose, swelling his eye (“Cut me, Mick”) and lasting a full 15 rounds. It’s ultimately hailed as “the greatest exhibition of guts and stamina in the history of the ring,” and while Adrian is not physically inside the ropes, she takes every punch with him. Thus, in the end, when Rocky has gone the distance, winning by his own standards, his love for her is all that matters.

The Real Rocky

While Rocky features several elements of previous films — Golden Boy (1939), On the Waterfront (1954), Marty (1955), Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956) — it mostly pulls its punches from a real-life. In March 1975, Stallone was in the crowd at Madison Square Garden to witness underdog Chuck Wepner nearly upset an unsuspecting Muhammed Ali, knocking the champ down and lasting until 19 seconds before the final bell.

This makes the cameo appearance by real-life boxing legend Joe Frazier all the more ironic. It was he who was Ali’s real-life rival, and you can bet Ali himself would try to upstage Frazier. That year at the Academy Awards, he playfully confronted Stallone, chanting, “I’m the real Apollo Creed! … I watched your movie. You stole my script!”

The chants of “you stole my script” weren’t far off. In 2003, Wepner filed a lawsuit claiming that he was entitled to $15 million for the unauthorized use of his name for promoting the film. (E) The backstory became the subject of a fascinating ESPN “30 for 30” documentary titled “The Real Rocky.”

Sly and His Script

At the time he saw the Wepner-Ali fight, Stallone was a mere dreamer working at the ticket window of a New York movie theater. His connection to the underdog story was real, having written 32 rejected scripts and still looking for his own big break. (E) He allegedly wrote Rocky over the course of one long weekend, pouring his own underdog dreams out onto the page. (A) When producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler offered him $265,000 for it, he held out for much less — $75,000 and a percentage of the profits — but with one important stipulation. He must be cast in the lead.

It was a big demand, as Stallone’s bit parts in Woody Allen’s Bananas (1971) and Roger Corman’s Death Race 2000 (1975) paled in comparison to the producers’ high-profile options of Robert Redford, Ryan O’Neal, Burt Reynolds and James Caan. (E) The shrewd offer turned out to be a very smart business move, as the film turned Stallone into an overnight success, riding the wave of the Rocky into the Rambo franchise and instant action hero status. Yet it leaves critics to wonder — was Stallone merely an opportunist?

“Stallone may be the most self-conscious noble savage since Mussolini,” wrote scholar David Thomson. “His weird monument, Rocky, is a fairy tale that fakes everything down to its own naievete. A large, domineering presence, Stallone is not casually nicknamed Sly. He is as nimble and cunning as a much smaller know-it-all. His script for Rocky and his way of selling its package were concocted with the same chutzpah: his version of an innocent oaf is shot through with poker-faced calculation. Those lavish spaniel eyes are worked on like a muscle. The appeal to little men is as much arrogant demagoguery as was Chaplin’s. And, since Chaplin, who has offered tramps with such velvety romantic eyes? Such men know they are really princes in disguise, and scorn ordinariness.” (A)

Indeed, Stallone knew exactly what he was doing. You can almost imagine producers Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff echoing the fight promoter, saying, “I like it! It’s very American,” and Stallone responding like Apollo, “No … it’s very smart.” Stallone had to have known he was no Paddy Chayefsky and his script was no Network, which beat Rocky for Best Screenplay and ranked 70 spots higher on the WGA’s Top 101 Screenplays.

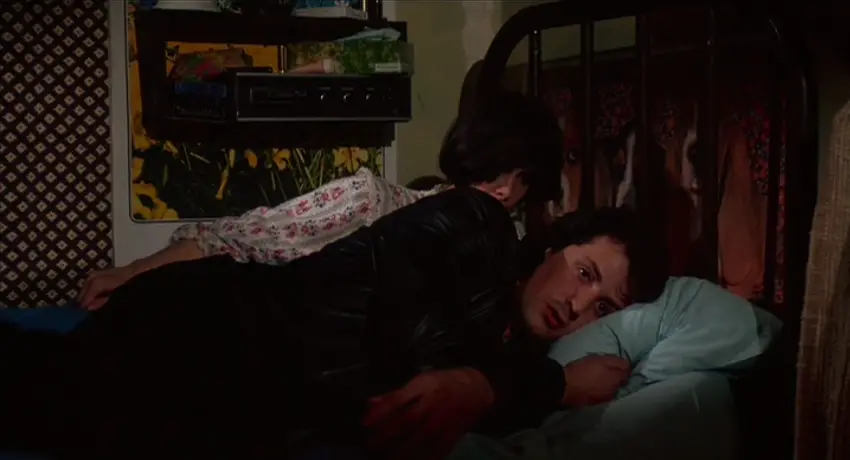

What he did know, however, was how to capture the imagination of audiences, how to write with pathos, and how to show phenomenal restraint in his film’s conclusion. Part of the reason Rocky works is Stallone’s insistence on the fight’s outcome, creating a winner out of a loser. This concept goes hand-in-hand with his ability to write masterful characters with clear needs. Rocky’s life need — to prove his worth — is brilliantly articulated in the scene right before the fight, as he crawls into bed with Adrian after a night of soul-searching:

ROCKY: I’ve been out there walkin’ around thinkin’. I mean who am I kiddin’, I ain’t even in the guy’s league. … Yeah, it don’t matter, ’cause I was nobody before. … I was nobody. But that don’t matter either, ya know? ‘Cause I was thinking, it really don’t matter if I lose this fight. It really don’t matter if this guy opens my head, either. ‘Cause all I wanna do is go the distance. Nobody’s ever gone the distance with Creed. And if I can go that distance, you see, and that bell rings and I’m still standin’, I’m gonna know for the first time in my life, see, that I weren’t just another bum from the neighborhood.

This “night of the soul” moment serves as a one-two punch with the film’s ending, allowing us to feel joy out of loss as the two lovers come together and, for the first time, say, “I love you.” What fitting last words to an amazing script. After all, Rocky is, at its core, a love story.

Can you imagine this final scene without the preceding bedside speech? Believe it or not, the “go the distance” speech was almost scrapped amidst the intense shooting schedule of 28 days and a mere $1 million budget. (E) When Avildsen decided to go ahead and shoot it, Stallone’s performance made the crew all misty-eyed and they realized it had to stay. The Academy rewarded him in kind, making Stallone just the third person in history to earn Oscar nominations for both writing and acting in the same film. His company? Charlie Chaplin for The Great Dictator (1940) and Orson Welles for Citizen Kane (1941).

As a performer, Stallone was never on the level of a Chaplin or a Welles, but what he lacked in acting skill, he made up for in charisma. It’s impossible not to smile each time he slurs “Hey, yo” in that dopey Philly accent; not to cheer when he lets out those primal cries, “Yo, Adrian!” — good for #80 on the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes. In Rocky Balboa, Stallone had created a lovable brute — a real rope-a-dope — and the AFI’s #8 Greatest Hero. Ellen Ripley, George Bailey and T.E. Lawrence were all forced to step aside.

Supporting Cast

In addition to Stallone, three other Rocky actors earned Oscar nominations. If Rocky were to get a nod, surely Adrian must, too. And thus, Talia Shire earned the second acting nomination of her career, following the sinister Connie Corleone in her brother Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II (1974). It would also be her last, as Shire gradually surrendered her career to the Adrian character. With each sequel, she became more and more typecast, and her limitations became more and more apparent. In Rocky, there are moments she achieves a genuine innocence, playing shy beauty to maximum effect as Stallone removes her glasses and lets down her hair. But there are also moments that are quite jarring, particularly when she grabs Paulie and screams “I am not a loser!”

Speaking of whom, Burt Young earned his own an Oscar nomination. Having trained under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, Young got his start playing thugs in films like The Gambler (1974) and Chinatown (1974), where Jack Nicholson memorably warned him “don’t eat the venetian blinds.” Next came his getaway driver in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite (1975), which set up his casting in Rocky, a role he reprised five times. It remains the only Oscar nomination of his career, which he lost to Jason Robards as Ben Bradlee in All the President’s Men (1976).

Speaking of whom, Burt Young earned his own an Oscar nomination. Having trained under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, Young got his start playing thugs in films like The Gambler (1974) and Chinatown (1974), where Jack Nicholson memorably warned him “don’t eat the venetian blinds.” Next came his getaway driver in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite (1975), which set up his casting in Rocky, a role he reprised five times. It remains the only Oscar nomination of his career, which he lost to Jason Robards as Ben Bradlee in All the President’s Men (1976).

Robards also beat out 69-year-old Burgess Meredith, who was the most

accomplished in the cast. He arrived as George in Of Mice and Men (1939) — referenced when Mickey visits Rocky’s apartment and says, “I seen your light, kid”). He played Ernie Pyle in The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), co-starred and produced Paulette Goddard’s The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946), appeared in a handful of episodes of The Twilight Zone (1959-1963), starred in Otto Preminger’s Advise and Consent (1962) and became a household name as the grunting Penguin in TV’s Batman (1966-68). But it was not until 1975 that he earned his first Oscar nomination in John Schlesinger’s The Day of the Locust (1975), which he followed up with another nomination for Rocky. Mickey was clearly the role of his career, playing it four times (once beyond the grave) and spitting classic lines with elderly grit: “You’re going to eat lightning, and crap thunder!” and “Women weaken legs!”

The only two major characters that didn’t get Oscar nominations were Joe Spinell, who joined Shire in adding some Godfather cred, and Carl Weathers, who returned for three more Rocky movies, using them to gain both Stallone-style action parts (Predator) and comedic sports roles (Happy Gilmore).

Avildsen’s Directing Upset

While none of the actors tasted Oscar gold, their director did — and film buffs are still bitter. That’s because John G. Avildsen beat out an insanely deep crop of fellow nominees — Sidney Lumet (Network), Alan J. Pakula (All the President’s Men), Lina Wertmuller (Seven Beauties) and Ingmar Bergman (Face to Face) — as well as those who were not even nominated — Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver), Hal Ashby (Bound for Glory) and John Schlesinger (Marathon Man). Scorsese’s snub gets “smelling salt” right in the wound just before the fight, as Rocky turns to Mickey: “Is he talking to me?”

I digress. Let us all take a deep breath. The awards have long been handed out, and history has corrected the record books. While Avildsen’s work in Rocky may not belong in the upper echelon of directors, there’s more to admire than you might think.

Cut Me Mick: Art of Montage

It’s fitting that two of Rocky‘s three Oscars went for Best Director (John G. Avildsen) and Best Editing (Richard Halsey and Scott Conrad). Together, the trio turned Rocky’s training regimens into the most famous montages in movie history.

Of course, academics might argue that Avildsen bastardized the technique to something beyond what was originally intended during the period of Soviet Montage. This early 20th century movement — hailed by Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin — invented montage as way to juxtapose two separate images to infer meaning symbolically. In other words, you show one thing (Shot A), you show another thing (Shot B), and when you cut them together (A+B), you create an entirely new meaning altogether (Meaning C). Thus the formula is Shot A + Shot B = Meaning C.

Of course, academics might argue that Avildsen bastardized the technique to something beyond what was originally intended during the period of Soviet Montage. This early 20th century movement — hailed by Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin — invented montage as way to juxtapose two separate images to infer meaning symbolically. In other words, you show one thing (Shot A), you show another thing (Shot B), and when you cut them together (A+B), you create an entirely new meaning altogether (Meaning C). Thus the formula is Shot A + Shot B = Meaning C.

Today, montages are instead used to simply show a lot of action in a condensed amount of time. Rather than A+B=C, it is all too often now A+B+C+D+E, and so forth, in an ongoing repetition of images that lack true understanding of the original concept, the glue of “meaning” between the cuts. This inferior new approach rose to popularity during the ’80s, its excess epitomized by Rocky IV, a Cold War boxing film that’s practically two straight hours of musical montage. How ironic that it took Rocky’s battle against a Soviet opponent for Hollywood to kill the Soviet montage.

All this said, the original Rocky picks its battles well. Just because Avildsen opened Pandora’s Montage Box, doesn’t mean he didn’t use them discriminately. There was no way to show Rocky training without a montage, just like there was no way to show 15 rounds against Apollo Creed without a montage. While the final fight sequence leaves much realism to be desired, its pacing is superb. Avildsen has our hopes rising and falling with the action, so by the time Rocky ignores Mickey’s advice to “stay down” and climbs back to his feet, we rise with him. Avildsen’s cut to a close-up of Adrian closing her eyes, then slowly opening them again to see her man still standing, still gives me the chills.

Room to Breathe

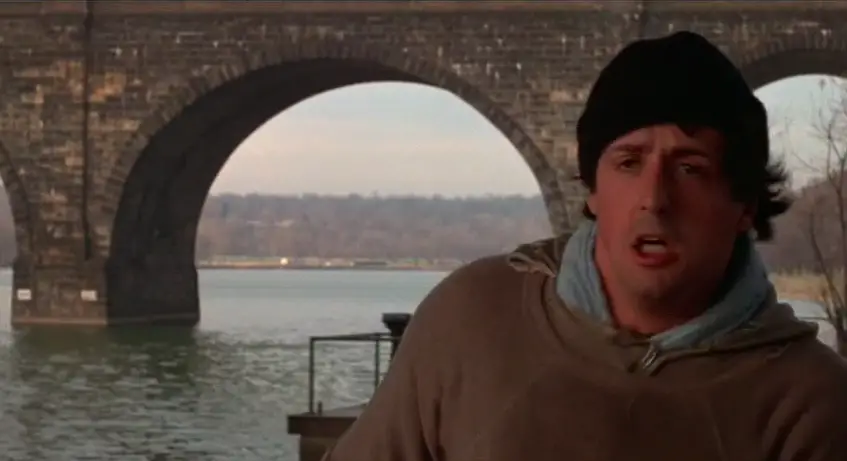

While Rocky is famous for those quick-cutting montages, it’s precisely the opposite moments that garner it some academic respect. Avildsen refreshingly lets certain shots breathe, making Rocky feel more like a piece of art than popcorn entertainment. Arguably the strongest shot in the entire training montage is when Avildsen lets his camera roll in a side-dolly as Rocky runs by the shipyard. Allowing this to play out in “long take” allows viewers to really digest the feat of Rocky (and Stallone) sprinting the length of the ship.

Avildsen again lets his shots breathe during the scene where Adrian visits Rocky’s apartment for the first time. Their first kiss is captured with the perfect level of intimacy, only few cuts, a slow crackling song playing on the record player. The handling of the space between them is masterfully done.

When Mickey comes to Rocky’s apartment to ask to be his manager, his arrival up the stairs is shot in a nice static “long take.’ The camera is like fate watching.

Similarly, the reconciliation between Rocky and Mickey occurs in a static, long-take wide shot outside Rocky’s apartment. We can’t hear what is said, but we know the two have come to terms.

Reflections and Push-Ins

Fortunately, Avildsen recognizes that Rocky is a film is all about character studies, both the director studying his characters through his lens, and the characters studying themselves on screen. Both are accomplished through a series of slow camera push-ins on each of the three main characters — Rocky, Adrian and Mickey. Each time cinematographer James Crabe slowly pushes in on each of them, it signifies a character study that is then explored the rest of the film.

Note that two of the above three shots feature characters looking at themselves in mirrors. These reflections become a sort of visual motif for Avildsen. Compare Rocky’s reflection in the video above to his reflection in the photo below. No longer does he have a bandaged eye and a ratty hat hanging next to the mirror. Instead, he stands in a robe with a towel around his neck and no bandage over his eye in a clean bathroom for a major prize fight. His fortunes are changing.

Avildsen has fun with this mirror motif, finding new ways to use it. In the tavern scene, Paulie stares into a broken bathroom mirror, the wall faded in a rectangle shape where the mirror used to be. Nothing better describes Paulie than this image — a broken man so in need of an identity that he can’t even see his own reflection.

Still, Avildsen’s most clever “mirror trick” comes in Rocky’s pet shop exchange with Adrian. For a long time I could not figure this one out — I just thought it looked cool. However, the next section explains the genius trick at work.

Escaping the Cage

The pet shop scene includes a brilliant piece of mise-en-scene involving a bird cage. Avildsen establishes the cage in a two-shot of Rocky and Adrian, where each stands on opposite sides of the cage, a couple of “love birds” not yet brought together.

The seminal shot of this scene comes with Adrian’s face literally appears behind the cage, symbolizing that she herself is living a trapped existence.

As Rocky asks to walk her home, we pan away to the reflection of him and her outside the cage. Rocky is her escape, but she is not yet ready to leap. So, he gives up and leaves, and sure enough, Avildsen pans back to Adrian inside the cage. Avildsen proves this “directing concept” is intentional in a later scene where Adrian decides to move in with Rocky. Note that an empty birdcage sits behind her in the background. She has escaped.

Pioneering the Steadicam

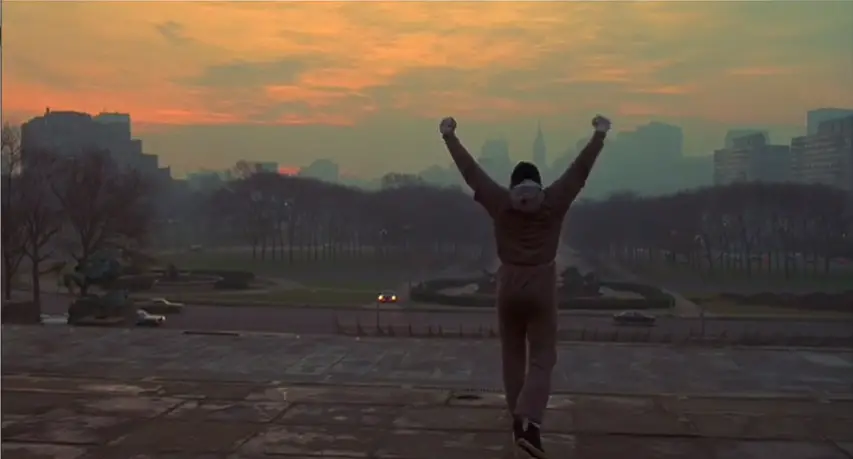

Finally, Avildsen deserves credit for creating one of the most iconic images in movie history — and pioneering a crucial piece of camera equipment in the process. As Rocky runs up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum, the camera tracks sideways up the stairs with him, then moves around behind him for that iconic shot of him thrusting his arms triumphantly into the air. With arms outstretched against the Philly skyline, it’s a beautiful metaphor for his own personal climb toward self-worth.

Avildsen achieved the shot in one of the very first uses of the Steadicam, a device that uses counterweights to allow the camera to move smoothly without a dolly track. Steadicam operator Garrett Brown actually ran alongside Stallone up the stairs, while the device kept the camera as smooth as possible. Rocky was one in a trio of films to first used the device, joining Ashby’s Bound for Glory and Schlesinger’s Marathon Man. Together, they popularized the Steadicam for Stanley Kubrick to use it in The Shining (1980) and for George Lucas in Return of the Jedi (1983).

Which brings us back to the Soviet Eisenstein, who had tracked the Odessa Steps in Potemkin, but needed a dolly track to do it. Indeed, the movie landscape was changing.

Soundtrack

Try watching the above scene without the music. Just try. It’s no longer the triumphant Rocky we know. It’s just a guy running up steps.

No doubt about it, composer Bill Conti created one of history’s most recognizable themes with the oft-imitated training anthem “Gonna Fly Now.” While its corny chorus chants of “Trying hard now!” date the film (along with several grainy ringside shots), its instrumental horns trumpet one of the classic movie songs of all time. The song may have lost the Oscar to Barbra Streisand’s “Evergreen” in the remake of A Star is Born, but it topped the Billboard charts in the first week of July 1977, won a 1988 ASCAP Award for “Most Performed Feature Film Standard” and placed #58 on the AFI’s 100 Movie Songs. How many movies do you go to today, whose songs actually top the charts of what you hear on the radio? Hardly any.

In addition to the main theme, Conti composes a beautiful set of music from start to finish. The street corner harmony of “Take You Back” (sung by Stallone’s brother Frank), sets the tone, while the horns of “Philadelphia Morning” make you want to wipe the sleep from your eyes, sniff the morning air, chug some raw eggs and go for a run. It’s here that Conti’s score most resembles Leonard Bernstein’s for On the Waterfront (1954).

The quiet piano notes of “Alone in the Ring” beautifully speak to the doubts of one staring directly at his dreams, while “Going the Distance” builds the tension all the way to its release in “The Final Bell.”

“Do you realize that it’s the first fight picture — at least the first fight picture I remember — in which the major battle was scored?” said Richard Brooks, director of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958). “The main fight in Rocky was scored from beginning to end with an eighty-piece orchestra. Take the score away, and you’ve got a fight. You put the score in and you’ve got Rocky. That’s the difference. People were cheering that fight, but they were cheering the music as much as the fight.” (C)

It’s hard to believe, but the song most associated with Rocky, Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” did not even arrive until the film’s third installment. It was No. 1 on the Billboard charts in 1982, served as the opening track of The Rocky Story soundtrack (1990), where “Going the Distance” was notably absent, and 24 years after its original recording, ranked No. 9 on Billboard’s Hot Ringtones of 2006. The song’s ongoing popularity is a testament to Rocky‘s ability to affect pop culture over a span of 30 years.

The Sequels

As with most movie franchises, the Rocky sequels were adored and hated from both sides of the spectrum. The series quickly became an abomination to all serious film minds, with each sequel deemed more ridiculous than the next and pegged as more commercial opportunism by their writer/director Stallone. To many mainstreamers, though, the continued films boosted the film’s pop culture lore. The way I see it, the Rocky franchise offered one work of equal parts art and entertainment (the original), followed by five sequels of mass entertainment.

Rocky II (1979) will please most die-hard fans, if only because it’s the least removed from the original magic. Fans finally get to see Rocky and Adrian marry, buy their first home and have their first kid. They also get the good old training montages, this time with Rocky donning his red Rambo headband and chasing a chicken released by Mickey. It all builds to a much anticipated rematch with Apollo — the one Apollo said would never happen and Rocky said he didn’t want — and culminates with the most contrived ending to a boxing match ever devised, with both fighters falling to the mat at the same time. At least we get the joy of seeing Rocky hoist the title belt above his head and proudly proclaim: “Yo, Adrian! I did it!” The film grossed $85.1 million upon release, and at 6.7 on IMDB and 68% on rottentomatoes, it’s the third highest rated Rocky film.

Rocky III (1982) was an obvious follow up, using the tried and true plot of a successful champ losing perspective and losing his title to a hungrier up-and-comer (as Apollo had in the first). Only here, the challenger is the viscious Clubber Lang (Mr. T), who knocks Rocky out moments before Mickey dies from a heart attack. Enter the most unlikely of friends, Apollo, who offers to train Rocky for a rematch with Clubber. He lends him his trusty American flag boxing trunks and helps him develop the “Eye of the Tiger,” a fancy term for killer instinct, setting up the song of the same name and lifting Rocky III to huge success. The third installment wound up grossing more than the original at $124.1 million. Today it carries mediocre ratings of 6.1 on IMDB and 65% on rottentomatoes, but is a favorite of many Rocky diehards.

Rocky IV (1985) was the highest grossing of the entire series at $127.8 million. Ask most mainstream viewers their favorite Rocky film, and many will say this one. It capitalized on Cold War sentiments by pitting Rocky against a seemingly indestructible Russian, Ivan Drago (Dolph Lundgren), who kills Apollo Creed in the ring. It’s a blast watching the Italian Stallion chopping wood and braving the Russian cold in an attempt to outwork Drago, and an even bigger blast watching him actually chop him down in the ring. As a youngster, it too was my favorite. Reviewing the film today with a critical eye, the film sorely lacks. In addition to the cheesy ’80s notion of a domestic robot, the Cold War themes feel all too calculated, paling in comparison to the real-life “Miracle on Ice” witnessed at the ’80 Olympics. Even our ill will toward the steroid-injecting Drago is compromised by our current knowledge of Stallone’s own dabbling in performance enhancers. Most of all, the film shows an over-reliance on montages, making Rocky IV more of a music video than an actual film. IMDB voters give it a measly 6.1, and critics rank it a sorry 44% on rottentomatoes. Still, it remains possibly my favorite guilty pleasure in movies, with a catchy soundtrack featuring Vince DiCola’s upbeat “Training Montage” and fight theme “War,” Survivor’s “Burning Heart,” Robert Tepper’s “No Easy Way Out,” John Cafferty’s “Hearts on Fire” and James Brown’s “Living in America,” which earned a 1986 Grammy. You could also argue that, no matter how clumsily handled, the film helped put an end to the Cold War. The Berlin Wall fell only a few years later.

Rocky V (1990) brought Rocky into the ’90s, shaking from the damage inflicted upon him by Drago. He’s forced to give up boxing for good, and he and Adrian decide to move back to Philly. Of course, the Rock misses the ring so much that he becomes a trainer for hot prospect Tommy Gunn (real-life fighter Tommy Morrison). In training Tommy, Rocky neglects his own son, Rocky Jr. (real-life son Sage Stallone), and then has his heart broken when Tommy jumps ship to a Don King-like promoter, George W. Duke (Richard Gant). The film ends with a street fight between Rocky and Tommy, the only in the series to end outside a ring. Despite its reunion with director John G. Avildsen, the film is widely considered the worst in the series, grossing the least at $40.9 million and earning a 21% on rottentomatoes and a 4.4 on IMDB. Of course, there are treats for the most diehard Rocky fans — the ability to see Rocky back in his original environment, flashbacks to Mickey after his absence in Rocky IV, and a closing montage of stills from all the great moments in the series, set to Elton John’s “Measure of a Man.”

Rocky Balboa (2006) lost a lot of people a lot of bets, the kind of friendly wagers that debated whether Stallone would leave well enough alone. Indeed, Stallone proved he couldn’t stop scratching that itch. It was the first film since the original not to attach a Roman numeral, perhaps because so many “Rocky VI” spoofs had already been made during the saga’s 16-year hiatus. It turned out to be a good omen, as the film grossed $70.2 million and earned a respectable 76% on rottentomatoes and 7.4 on IMDB — much better than Stallone’s Rambo (2008) reboot. It was also the first film without Adrian (dead before the film’s start), the first with actual HBO Boxing announcers Jim Lampley and Larry Merchant, and the first against a real-life boxing champ, Antonio Tarver, playing the ridiculously named Mason “The Line” Dixon. As Rocky makes his way to the ring for his final fight, Paulie takes him aside and says, “I know you got a lot of stuff to get out of your system. But get rid of the beast. Let it be done forever.” The line, written by Stallone himself, is an admission that this whole Rocky thing had become an uncontrollable beast and this final film was a solid attempt to bury it forever.

Pop Culture

As long as there is television, these six films will loop eternally on cable marathons. Rocky may have had a larger impact on pop culture than any other film, inspiring references in everything from movies to television, music to video games.

Oddly, the first indication of the pop references to come happened with the re-release of Stallone’s earlier soft-core porn flick, Party at Kitty and Stud’s (1970), re-named The Italian Stallion (1976). The references continued in Saturday Night Fever (1977), whose own Italian-American underdog has a Rocky poster on his wall. And Eddie Murphy cracked a number of Rocky jokes in Eddie Murphy Raw (1987). Viewer discretion advised.

Rocky spoofs made great fodder for late night sketch comedy. Saturday Night Live had some hilarious skits, while Jim Carrey memorably played the Italian Stallion on In Living Color.

You could also say Rocky enabled the success of the WWF (now WWE), as Rocky III popularized both Hulk Hogan and Mr. T, who would become the main eventers in the very first Wrestlemania. You can still hear chants of “Rocky” whenever The Rock takes the ring. The film also inspired this spoof between Vince and Shane McMahon.

The training sequences in Nintendo’s Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out are very reminscient of Rocky.

And it would be way too much to mention all the other movie references, but memorable ones include Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990), where Michaelangelo does his best Rocky impressions; Encino Man (1992), where Link chugs raw eggs during his training montage; Pulp Fiction (1994), where Butch calls out Fabienne’s name like Rocky’s call to Adrian; The Program (1993), where Omar Epps takes Halle Barry on an ice rink date, admitting he saw it in Rocky; and Happy Gilmore (1996), where Adam Sandler does the same.

Rap music took its turn. The Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy and Busta Rhymes turned “Going the Distance” into “Victory” for the opening track of the Puff Daddy and the Family album. Later, the Big Tymers recorded a song called “Rocky Balboa” and MOP sampled “Eye of the Tiger” in “Four Alarm Blaze.”

In a memorable Starbucks TV commercial, Survivor spoofed “Eye of the Tiger” by singing, “Roy, Roy, Roy!”

And in my all-time favorite Rocky reference, South Park had Randy Marsh channel Rocky by challenging a fellow little league dad (“The Bat Dad”) to a fight.

Legacy & Inspiration

The impact of Rocky on sports and sports films is unprecedented. In December 2010, Stallone was voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame — yes, an actor was voted into a sports hall of fame. When it came time to make The Karate Kid (1984), Avildsen you can bet Avildsen was asked to direct, Conti was tapped to score and the main character was given a Mickey-esque mentor in Mr. Miyagi. The tale has become the winning formula for all underdog sports movies, regardless of sport — boxing (Cinderella Man), football (Rudy), horse racing (Seabiscuit), golf (The Greatest Game Ever Played), baseball (Major League) and basketball (Hoosiers).

As such, Rocky was the very first sports movie to ever win Best Picture, charting a path for the likes of Chariots of Fire (1981) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). It’s only fitting then that both Sports Illustrated and ESPN Page 2 named Rocky the #2 sports movie of all time. The AFI followed suit, ranking the film #2 on its Top 10 Sports Movies, behind only Raging Bull (1980). Athletes everywhere replay the film in their head each time they get ready to go for a run, recreating our own Philadelphia mornings. To say it should be required viewing for all athletes is redundant, because it already is.

And yet, the film succeeds well beyond the realm of sports. Rocky’s rags-to-riches journey applies to all walks of life. It’s a lesson in wanting something more than the other guy and making the most of the opportunity when it comes along. Rooting for Rocky is the easiest pathos in movies, because the film’s basic premise and tagline — “His whole life was a million to one shot” — speak to something basic in us all — the notion that we are all capable of bettering ourselves. This was the emotion that carried the film upon release in 1976, as audiences literally stood and cheered in theaters. (D) People couldn’t get enough as Rocky grossed more than $117 million, while total domestic box office from all the films exceeded $565 million. (E)

“I guess what Rocky did was give a lot of people hope,” Avildsen said during his Oscar speech. “And there was never a better feeling than doing that.”

This is why the film ranked all the way at #4 on the AFI’s 100 Cheers, a list of the most inspirational movies of all time. It placed with some pretty elite company, finishing behind only It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Schindler’s List (1993).

The AFI has rained accolades rather triumphantly on Rocky, including #7 Heroes (Rocky), #80 Quotes (“Yo, Adrian!”), #58 Songs (“Gonna Fly Now”) and #42 Thrills. Somehow, the film didn’t make the AFI’s 100 Passions, which is a shame. You’d be hard pressed to find two more famous lovers than Rocky and Adrian.

No matter, on the AFI’s biggest list, the AFI Top 100: 10th Anniversary Edition, Rocky ranked #57, jumping a full 21 spots from the AFI’s original list in 1997. This is a credit to the AFI’s willingness to at least include some mainstream hits. Those lists which choose not to include Rocky might just be too snobby for their own good. The film received just one vote on the 2002 Sight & Sound international critics poll, not even close for a spot on the list.

In a way, this listology debate echoes that which has unfolded on the very art museum steps Rocky climbed. A bronze Rocky statue was unveiled there in 1983, putting the Rocky Steps on par with Constitution Hall and the Liberty Bell as must-sees for Philly tourists. Sadly, the statue was at one point removed because it wasn’t considered “art,” echoing the sentiments of many a Sight & Sound voter. Fortunately, it was moved back in 2006, showing our capacity to recognize a great movie’s impact on a culture. Where did the statue reside while it was away? What sports arena served as its temporary home while officials hashed out this debate of art vs. entertainment? The Spectrum.![]()

Citations:

CITE A: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE B: Gerald Mast, A Short History of the Movies

CITE C: Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (p. 537)

CITE D: AFI 100 Years…100 Cheers, CBS special

CITE E: filmsite.org