Director: Michel Gondry

Writer: Charlie Kaufman (screenplay/story), Michel Gondry (story), Pierre Bismuth (story)

Producers: Anthony Bregman, Steve Golin (Focus Features, Anonymous Content)

Photography: Ellen Kuras

Music: Jon Brion

Cast: Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Elijah Wood, Kirsten Dunst, Tom Wilkinson, Gerry Roberty Byrne, Thomas Jay Ryan, Mark Ruffalo, Jane Adams, David Cross, Ryan Whitney, Debbon Ayer, Amir Ali Said, Brian Pirce, Paulie Litt, Josh Flitter, Lola Daehler, Deirdre O’Connell

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- Jim & Kate: Cast Against Type

- Supporting Cast

- Screenplay Gold

- Soundtracks & Sound Tricks

- From MTV to Movie Screen

- Cinematic Perspective

- Blocking & Choreography

- Fracturing Time & Space

- Visual Genius

- Props, Colors & Familiar Image

- Legacy

“I can’t remember anything without you.”

“That’s sweet. But try.”

How brilliant a writer is Charlie Kaufman? Brilliant enough to earn three Oscar nominations and contribute three scripts to the Writers Guilds’ 101 Greatest Screenplays of All-Time — all in a span of six years. From 1999-2004, Kaufman single-handedly gave us some of the most imaginative screenplays in the history of movies, from Being John Malkovich (1999), about a puppeteer finding a hidden doorway into the head of actor John Malkovich, to Adaptation. (2002), about twin-brother screenwriters, earning Nicolas Cage an Oscar for playing both Charlie Kaufman and his brother Donald.

Yet as phenomenal as those scripts are — and they are mind-blowing — Kaufman’s most lasting and touching work remains Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, a film about ex-lovers who undergo a procedure to erase eachother from their respective memories. If only Jimmy Stewart had that luxury in Vertigo. And yet, Eternal Sunshine is so much more than its original, bittersweet premise. Kaufman layers his gimmick with deep characterization, beautiful themes and wondrous science fiction. Of the three aformentioned scripts to land on the WGA list, Eternal Sunshine ranks the highest at #24, above such classics as The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Double Indemnity (1944). And while Malkovich and Adaptation. did not win Kaufman Oscars, Eternal Sunshine finally did the trick, winning Best Original Screenplay, an award he shared with director Michel Gondry (story) and Pierre Bismuth (story).

Plot Summary

Not to be confused with Kaufman’s previous script — Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), directed by George Clooney — Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind gets its title from Alexander Pope’s poem Eloisa to Abelard: “How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot! The world forgetting, by the world forgot. Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind! Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d.”

It begins with the end, with Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) getting an unexplained urge to skip work and take a train to Montauk. There he crosses paths with neon-haired Clementine (Kate Winslet), who he swears looks familiar. A romance blossoms, until a mysterious boy, Patrick (Elijah Wood), knocks on the window of Carrey’s car.

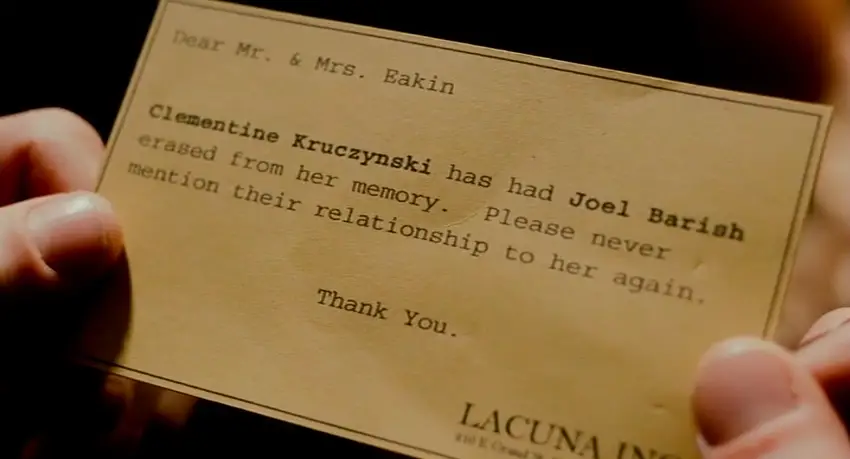

Enter the opening credits, a full 17 minutes into the film, signaling one long flashback of the events that brought us to this point, including subtle things like why Joel has a huge dent in his car door. We learn that Joel and Clementine recognize each other for a reason. They had once been in a serious relationship that ended horribly, breaking both their hearts, after which Clementine had all memory of Joel erased in a revolutionary new procedure by the biotech company Lacuna.

As his only means of moving on, Joel decides that he, too, will get the operation. He seeks out Lacuna founder Dr. Howard Mierzwiak (Tom Wilkinson), brings in a box of Clementine mementos and agrees to undergo anesthesia while Lacuna erases all memory of her. While sedated, he enters the deep recesses of his brain, surrounded by his most charished memories playing out with the kind of unpredictable, fragmented structure of someone in a dream they can’t wake up from.

In replaying his many memories with Clementine, “Dream Joel” discovers that he’d rather not forget about her and decides to call off the operation. The only problem is that “Real Joel” is still sedated and has no way of telling the Lacuna scientists he wants out. He can only lie unconscious as Dr. Mierzwiak’s young assistants, Patrick (Wood), Mary (Kirsten Dunst) and Stan (Mark Ruffalo), erase all his Clementine memories. Unfortunately for Joel, the wily Patrick has stolen Joel’s box of Clementine mementos and is using them to win her over, inserting himself into fond Joel moments she has long since forgotten. Meanwhile, Mary and Stan use Joel’s unconsciousness as an excuse to party on the job. Putting the erasure procedure on autopilot, they dance, drink, smoke and have sex right in his presence.

The three Lacuna youth are so distracted that they miss crucial signs that Joel is trying to stop the procedure. They don’t even notice when Joel discovers a way go “off the map,” tucking Clementine away into secret memories where she never existed before — like those from his childhood. This causes both tender moments, like a toddler Joel saying to a toddler Clementine, “I wish I knew you when I was a kid,” and awkward ones, like Clementine watching Joel’s mother catch him masturbating.

When Mary and Stan finally realize what Joel has done, they call Dr. Mierzwiak in a panic. The master arrives and helps them hunt Clementine down to erase her. In the end, with all other shared memories erased, Joel and Clementine work all the way back to their first memory together, which will also be their last, once it’s erased. There they make a pact to meet again in the real world, which brings us back to the beginning of the film, which is actually the end, where Joel encounters Patrick knocking on his car door.

Will Clementine choose to stay with Patrick, or take a chance with Joel? As both Joel and Clementine learn of a past relationship so tumultuous they had it erased, will they choose to go through with it anyway? The ending is the final genius touch of Kaufman’s script, leading up to the most powerful “OK” in movies.

Jim & Kate: Cast Against Type

“Jim Carrey and I, for a start, paired together, it’s a really unlikely pairing,” Winslet said. “You would not imagine he and I would end up doing something like this together, and everyone’s playing completely against type. I’m playing the Jim Carrey part and he’s actually playing the sort of Kate Winslet part.” (A)

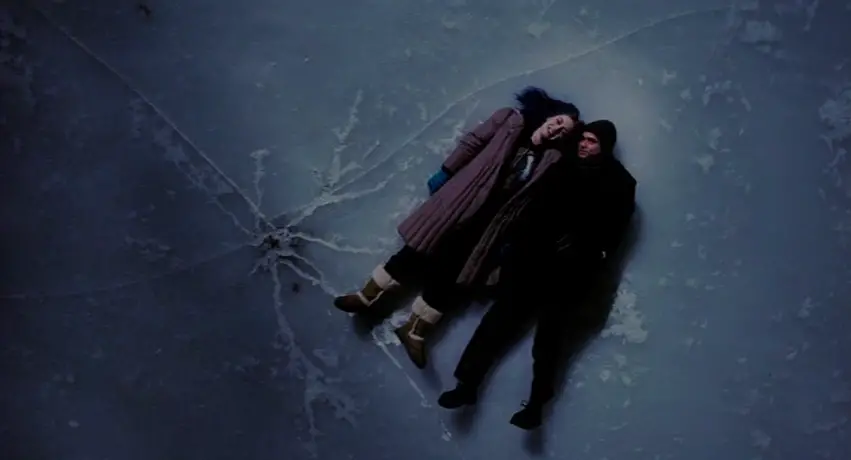

By that she means Carrey plays someone reserved and internal, and Winslet plays the wild, impulsive one. Note how when they go for a night picnic on a frozen river, Carrey is the one who says, “What if it breaks?”, while Winslet is the one who says, “What if? Do you really care right now?” That’s good character development by Kaufman. It’s also fertile ground for each actor to explore parts of themselves they never knew existed.

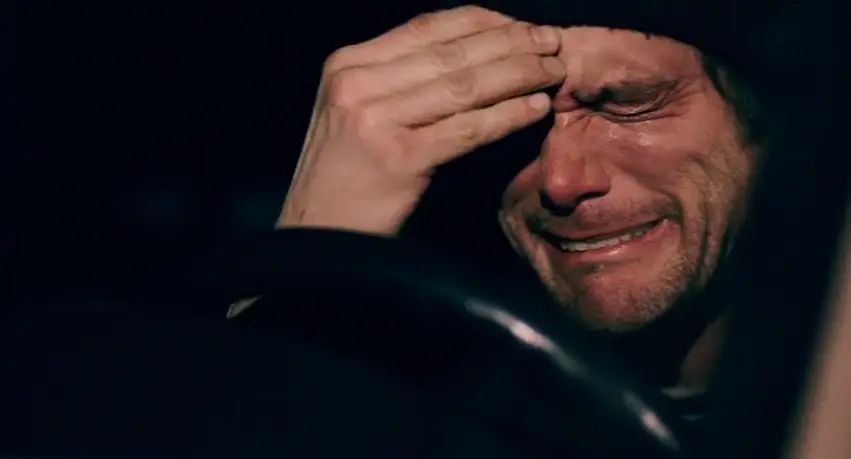

For Carrey, even his look was different, with longer hair, black skull cap and scruffy chin. A Golden Globe nomination marked his arrival as a dramatic actor, but it was a role he had been preparing for his entire career. Carrey always seemed like a man with little privacy to his own thoughts, sharing them with animals in Ace Ventura (1994); forfeiting them completely in Dumb and Dumber (1994); misplacing the truth in Liar, Liar (1997); sharing his most intimate moments with reality TV cameras in The Truman Show (1998); fighting a failed memory in The Majestic (2001); dividing his thoughts among split personalities in Me, Myself and Irene (2000); and hearing voices of all those mortals praying to his omniscience in Bruce Almighty (2003). Having a Lacuna van follow him around and erase his memories in Sunshine was only the next logical step.

As for Winslet, the role earned her a Golden Globe nomination as well, only she did Carrey one better by earning her fourth Oscar nomination, after Sense and Sensibility (1995), Titanic (1997) and Iris (2001). Clementine allowed her to break out of the ladylike corsets and period European garb she was used to, and try out a different side of herself: eccentric, talkative and following the motto, “I’m just a fucked up girl looking for my own piece of mind. I’m not perfect.” Though she lost to Hillary Swank for Million Dollar Baby (2004), Eternal Sunshine kept her Oscar streak going, leading to another nomination for Little Children (2006) and finally a win for The Reader (2008). By then, I guess the Academy had decided six nominations was enough.

Supporting Cast

The “cast against type” mantra continued with the supporting cast. In his first role since Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings Trilogy  (2001-2003), Elijah Wood sports sideburns, drinks beer and steals women’s underwear. Meanwhile, Kirsten Dunst broke from her own blockbuster franchise, playing the opposite of her M.J. character in Spiderman (2002-2007). As the morally ambiguous Mary in Sunshine, Dunst proves what we had already learned in Interview with a Vampire (1994) and

(2001-2003), Elijah Wood sports sideburns, drinks beer and steals women’s underwear. Meanwhile, Kirsten Dunst broke from her own blockbuster franchise, playing the opposite of her M.J. character in Spiderman (2002-2007). As the morally ambiguous Mary in Sunshine, Dunst proves what we had already learned in Interview with a Vampire (1994) and

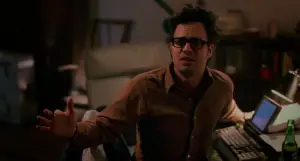

The Cat’s Meow (2001) — that she can most definitely act. What a gift from Kaufman to give Dunst a pothead extrovert who turns out to have a surprising vulnerability, thanks to a brilliant plot twist. By the end of the film, we’re just as much rooting for her relationship with Ruffalo, a pop teen favorite for 13 Going on 30 (2004) and a critics’ favorite for You Can Count on Me (2000).

The Cat’s Meow (2001) — that she can most definitely act. What a gift from Kaufman to give Dunst a pothead extrovert who turns out to have a surprising vulnerability, thanks to a brilliant plot twist. By the end of the film, we’re just as much rooting for her relationship with Ruffalo, a pop teen favorite for 13 Going on 30 (2004) and a critics’ favorite for You Can Count on Me (2000).

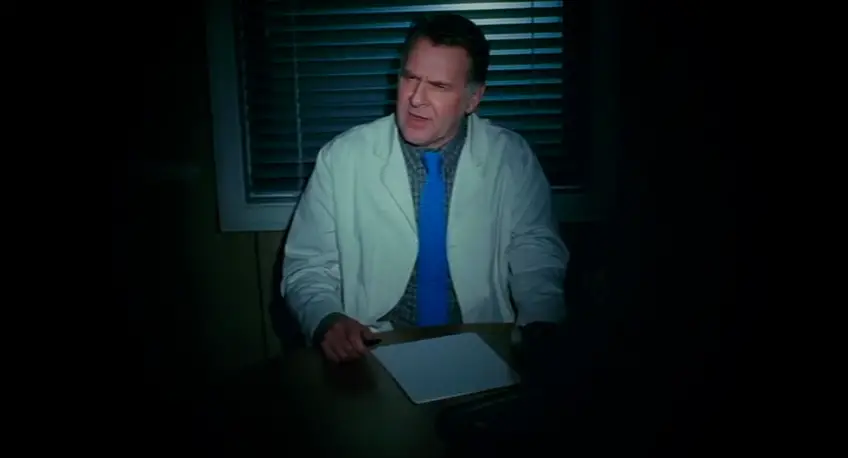

Who better to oversee this band of young actors than the consummate actor Tom Wilkinson, marking the midpoint between Oscar nominations for In the Bedroom (2001) and Michael Clayton (2007). His Lacuna doctor/mentor may be the most interesting character in the entire film, a god-like figure pulling all the strings and erasing the memories of others while keeping his own intact. Dr. Mierzwiak embodies the film’s entire moral dilemma, and Wilkinson has the chops to carry it.

Screenplay Gold

When you see the film, you can just imagine Carrey, Winslet, Wilkinson, Wood, Dunst and Ruffalo putting down Kaufman’s script and saying, “I must make this movie.”

The script features a brilliant premise (see plot summary), complex characterizations (see cast notes) and crafty dialogue, like, “Sand is overrated. It’s just tiny, little rocks.” More than any of this, Kaufman layers his script with some immensely powerful themes. The moral dilemma of the entire Lacuna operation is present throughout, particularly in those scenes where Dr. Mierzwiak rationalizes his erasure procedure. “Well, technically speaking, the operation is brain damage,” he says. “But it’s on par with a night of heavy drinking. Nothing you’ll miss.” Who’s to say?

When he touts the benefits of the surgery, he says, “Miss Kruczynski was not happy and she wanted to move on. We provide that possibility.” But is that right? Like Frankenstein (1931) before it, Eternal Sunshine plays off the danger of humanity attempting to play God. It asks what we give up when we obtain that power.

Beyond such meditation on what humanity is meant and meant not to do, the true greatness of Kaufman’s script is how he applies that to love. Kaufman took all previous notions of memory — the idea of implanting memories in Total Recall (1990); the idea of fractured memories in Memento (200); the idea of false memories in Minority Report (2002) — and created something completely original.

If those other movies had used the concept of memory manipulation for thrills, Kaufman explores its effect on the emotions; how the shared memory of two lovers is the most powerful form of memory there is. He reminds us that even our bad memories help shape who we are, and to go back and remove those would be catostrophic, akin to removing one’s own life in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

A similar theme pervades two other scripts released that same year, all within two months of each other — The Butterfly Effect, where Ashton Kutcher travels through his memories via magical diary entries; and 50 First Dates, produced by the same company as Eternal Sunshine, where Adam Sandler tries to win the heart of an amnesiac Drew Barrymore. All three are rather enjoyable films, but Eternal Sunshine puts the others to shame. Kaufman’s script is so thematically deeper, at times just as funny, far more meticulously structured, with far more complex characters and a style that gives one hope that cinema is still alive, exciting and dangerous.

Pluck Eternal Sunshine out of the cinematic timeline and you lose the inspiration for the voiceover in Stranger Than Fiction (2006), the greeting card lament of (500) Days of Summer (2009) and the dreams within dreams of Inception (2010).

Ultimately, though, the core of his story is about looking for the best in people, particularly our lovers. His message is that no matter how much you hate certain aspects of someone, if you want to make it work, you will suck it up and make it work. To learn and to change are the script’s biggest values, decrying the notion of blocking out the past.

Soundtracks and Sound Tricks

Kaufman’s message is beautifully captured in the film’s final song, Beck’s “Everybody’s Gotta Learn Sometime.” The lyrics leave viewers with much to ponder as the opening credits roll: Change your heart / Look around you / I need your lovin’ like the sunshine / And everybody’s gotta learn sometime. It’s just one of many superb song selections by director Michel Gondry.

On numerous occasions, Gondry messes with the relationship between sound and image. Note the illusion of non-diagetic sound (music outside the movie) when it’s actually diagetic (music coming from an on-screen source). Gondry fools us into thinking we’re hearing a film soundtrack, when all the sudden, Carrey pops a cassette out of a tape player and puts on new music — composer Jon Brion’s musical score.

Gondry continues to mess with the audio/video interplay throughout the film, from Joel’s inner thoughts serving as voiceover narration to his own memories, to Joel hearing the voices of the Lacuna erasers off screen while the dream sequence plays out on screen.

From MTV to Movie Screen

Gondry’s unique understanding of mixing sound and image stems from his background directing music videos. He started out in a a Parisian art school, where he formed the band Oui-Oui and shot their music videos with a groundbreaking style. When one of these videos aired on MTV, it caught the eye of Bjork, who asked Gondry to make her first solo video for “Human Behavior.” She liked his work so much on that video that they agreed to work on five more music videos together.

With the help of cinematographer Jean-Louis Bompoint, Gondry became a smash in the advertising world, a real “man man.” He directed commercials for the biggest companies around, including Gap, Smirfnoff, Air France, Nike, Coca Cola, Adidas, Polaroid and Levi.

Hollywood caught wind of this rising talent on the music video circuit, and asked him to direct Kaufman’s follow-up script to Being John Malkovich, the dramedy Human Nature (2001), which played at the Cannes Film Festival. This planted the seed for the two to want to work together again, and when they finally reteamed, the result was Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, where Gondry would do his most fascinating work yet. While Kaufman’s script is easily one of the finest ever written, it’s Gondry’s interpretation of that script that proves just as important.

Cinematic Perspective

Gondry’s edgy directorial style is not all uneasy handheld cameras and trippy montages of fractured memories. Any filmmaker today can do that. What sets Gondry’s work apart in Eternal Sunshine is the amount of thought he puts into his shots.

Like a young Orson Welles constructing giant windows and fireplaces to dwarf his characters in Citizen Kane (1941), Gondry shows similar ambition. Note the scene where Joel thinks back to his childhood, and suddenly Carrey is a kid sitting beneath a kitchen table. Rather than a computer program making Carrey appear smaller, Gondry had his set designers build a gigantic table for Carrey to sit under, as well as an entire giant kitchen set, all the way down to enlarged chocolate chip cookies. On this same set, he had a life-size Winslet stand in the foreground, using the science of perspective to create the illusion that she is much larger than Carrey. As Carrey climbs out from under the table and stands diminuitively in front of the giant stove, one can’t help but think of Kane.

Gondry again uses perspective in the scene where a tiny Carrey and Winslet take a sink bath together in an over-the-shoulder shot of Clementine’s lifesize mother.

Blocking & Choreography

In addition to blocking as a means of toying with perspective, Gondry also uses it to mess with his characters’ spacial relationships. Consider the scene where Winslet gathers her things and storms out of Carrey’s apartment. The entire thing is done in one continuous take, with no cuts and no CGI, only carefully-choreographed blocking and trap doors.

The shot begins with Winslet storming into the bathroom and the camera tracking behind Carrey as he follows her. When he arrives in the bathroom, Winslet is gone (having exited through a secret door), so he turns back and finds her magically in the kitchen. As Winslet exits again, the camera pans left and suddenly she’s magically outside the front door. The entire thing is done in one continuous take with no cuts and no CGI. In short, Gondry is busting his ass to give us art.

“That’s like a ballet, like a choreography, and I think the actor really enjoys doing that,” Gondry said. “It’s way more exciting for them to shoot this way than to shoot with blue screen.” (A)

Carrey agreed: “To be able to go, here’s a 75-watt bulb and you’re going to run around the wall, take your clothes off and come out the other side and be a different person — whatever it is, he makes it all happen in the camera. There’s no special effects. It’s all done right in front of the camera.” (A)

Fracturing Time & Space

Throughout the film, Gondry finds new ways to fracture both time and space. We get our first taste of this during Joel’s initial plunge into his memories, where he appears in the same room with himself. Gondry constructs the scene mostly in separation, cutting back and forth between the two Joels, but also a shot over Joel’s shoulder as witnesses himself in the doctor’s chair.

Gondry continues to take pleasure in disorienting us in space (3D) and time (4D). Note the shot of Joel walking down the street, listening to the “voices in his head,” only for Gondry to whip pan away to see Joel lying on an apartment floor next to a sofa bed, which folds up in rapid reverse motion until Joel sits with Winslet, eating Chinese food.

Note also the backward tracking shot with Carrey leaving a Barnes and Noble bookstore. As the lights systematically shut off behind him, Carrey passes through a doorway and is suddenly standing by the staircase of a suburban home. Wild stuff.

Visual Genius

At times it seems Gondry is a kid in a candy shop, trying out clever visual tricks just because he can — Winslet being yanked away into darkness; characters’ faces turning to mush; extras literally disappearing from a train station; rain pouring down indoors; and ocean surf rushing onto the floors of a home.

The craziest in this regard might just be the scene where Carrey and Winslet are dubbing their own voices to a drive-in movie. Suddenly, the movie fades from the screen, Winslet disappears, Carrey fights for her to reappear, then the two take off running to escape a disappearing car, then a disappearing fence.

“Michel, he really is a visual genius,” Winslet said. “… The things that he does through the lens, by just twisting a light or putting in panes of glass and making me be present in a frame then disappear literally in front of your very eyes, it’s like magic.” (A)

One can easily imagine a lesser director looking at a script like Eternal Sunshine and writing up a list of all the requisite computer-generated elements. Not Gondry. Dunst and Wood must have been perplexed after their CGI stints with Peter Jackson and Sam Raimi. What a testament to Gondry’s seriousness that he insist that all aspects of the film, including visual effects, be created organically.

Of course, Gondry’s hand may have been forced to go to such creative lengths. At $20 million, the independent film was very low budget, and creative solutions were much cheaper than computer renderings.

Props, Colors & Familiar Image

Gondry demonstrates complete control over every aspect of the film, all the way down to the art department. He works with the hair and make-up department to establish a consistent color palate, particularly for Clementine, who sports oranges and blues in everything from her wardrobe to her dyed hair.

Gondry also enlists the prop master in achieving familiar image, planting props from Joel and Clementine’s past, including a cloudy-sky pillow case and a coffee mug sporting a photo of Clementine.

It’s fun to look for these items throughout the film.

Legacy

Eternal Sunshine ranked a lowly 80th in the year’s top box office earners, but it still was a nice return on investment. The film grossed $34 million, a full $14 million more than it cost production companies Focus Features and Anonymous Content to make.

It was in DVD form that the film founds it audience, as superb reviews and word of mouth made it an essential rental. Today, the film carries a 94% on rottentomatoes — a critics’ seal of approval. The public has also signed off on it, voting it into the Empire Top 201 fan poll and as high as #62 on the IMDB Top 250. So when you see the film’s poster on Seth Rogen’s wall in Knocked Up (2007), it’s the mark of a generation’s approval.

Because of its 2004 release, the film just missed the flurry of turn-of-the-century best lists. Still, it was curiously left out of the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (2004), losing out to contemporaries like Million Dollar Baby, The Passion of the Christ, Collateral and The Aviator. I’d put this film up against any of those any day.

It’s really anybody’s guess as to how Eternal Sunshine will fare in the future. Will it gain listology steam over the years? Or will it be hailed solely as a great creative script? Will it go down as one of the best films of all time, or will it be forgotten like so many a Joel and Clementine memory? Stay tuned.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: DVD Bonus Feature: A Look Inside