Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Writers: Francis Ford Coppola (screenplays), Mario Puzo (novel)

Producers: Albert S. Ruddy; Francis Cord Coppola, Gray Frederickson, Fred Roos (Paramount)

Photography: Gordon Willis

Music: Nino Rota, Carmine Coppola

Cast: Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, James Caan, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, John Cazale, Richard Castellano, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, Talia Shire, Al Lettieri, Abe Vigoda, Giani Russo, Al Martino, Morgana King, Lee Strasberg, Michael V. Gazzo, G.D. Spradlin, Bruno Kirby, Richard Bright, Gastone Moschin, Tom Rosqui, Bruno Kirby, Dominic Chianese

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary (Part I)

- Plot Summary (Part II)

- History’s Deepest Cast

- Brando & DeNiro: Two Oscars, One Role

- Al Pacino: Made Man

- Screenplay: Structure, Character, Dialogue

- Accessibility Issues

- Coppola & The Hollywood Renaissance

- The Puppetmaster

- Fatherhood & Family

- Masculinity & The Patriarchal Society

- Religious Hypocrisy

- Political Corruption

- Corruption of Justice

- Corruption of Entertainment

- Business Corruption

- The American Dream Perverted

- Dangerous Oranges

- Foreshadowing in Mise-en-Scene

- Transitions & Parallelism

- Michael Off the Rails

- Gordon Willis: Prince of Darkness

- Art Department

- Soundtrack

- Pop Culture

- Legacy: Favorite vs. Greatest

Introduction

Considering their spots atop just about every best list in existence, the idea that The Godfather and The Godfather Part II are the greatest films ever made may seem more like a sacred truth than something still up for debate. To this day, they remain the only original and sequel to both win the Oscar for Best Picture. And yet, I have still heard an unfortunate few say they don’t get the hype. Too long. Too slow. Too depressing. If you fall into this category, I beg you to reconsider. If you like movies, and their potential to explain the world around us, I promise this is a bandwagon worth joining.

I’m reminded of an episode of Family Guy, where Peter and Lois argue over the film’s merits. Lois is taken aback by Peter’s taboo admission, “I did not care for The Godfather. Couldn’t get into it.” She’s almost offended, arguing, “It’s like the perfect movie!”

Clearly, I agree with the latter, that Francis Ford Coppola’s films are the perfect American saga, the most deeply thematic, tone specific, meticulously directed, well written, acted, shot, lit, edited, scored, quoted, imitated, popular, critically acclaimed, culturally significant films in the history of movies.

How’s this for an offer you can’t refuse: my promise that by the end of this review, if you truly take the time to read the litany of Coppola’s genius directing techniques and powerful themes, you will finally understand why these movies are so famous, so beloved and so revered. As the late Sidney Lumet said, “They are as close to perfect movies as I think exists.”

Plot Summary (Part I)

Based on the 1969 bestseller by Mario Puzo, The Godfather opens with a wedding reception at the Corleone estate in 1946 New York. The actual wedding couple, Connie Corleone (Talia Shire, Coppola’s sister) and Carlo Rizzi (Gianni Russo), are but minor players in the soup of more important characters we meet. We’re introduced to the four Corleone brothers — the hot-tempered, philandering Sonny (James Caan); the wimpy Fredo (John Cazale, then-husband to Meryl Streep); the adopted consigliere Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall); and war-hero Michael (Al Pacino), arriving later than the rest and bringing with him his WASP girlfriend, Kay Adams (Diane Keaton). From the get-go, we learn Michael is the only one who has not gotten mixed up in the family business, widely known to be organized crime. “That’s my family,” he tells Kay. “It’s not me.”

The head of the family, and broader crime Family, is The Godfather himself, Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando). He takes time out of the festivities to meet with the line of people waiting to take advantage of an Italian tradition that no man can refuse a request on his daughter’s wedding day. These guests include undertaker Bonasera (Salvatore Corsitto), body guard Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana) and Vito’s superstar godson crooner Johnny Fontaine (Al Martino). When the lattermost asks for a part in a movie, The Godfather immediately sends Tom to make Hollywood director Jack Woltz (John Marley) an equestrian “offer he can’t refuse.” Needless to say, Johnny gets the part. That’s The Godfather’s power.

The head of the family, and broader crime Family, is The Godfather himself, Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando). He takes time out of the festivities to meet with the line of people waiting to take advantage of an Italian tradition that no man can refuse a request on his daughter’s wedding day. These guests include undertaker Bonasera (Salvatore Corsitto), body guard Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana) and Vito’s superstar godson crooner Johnny Fontaine (Al Martino). When the lattermost asks for a part in a movie, The Godfather immediately sends Tom to make Hollywood director Jack Woltz (John Marley) an equestrian “offer he can’t refuse.” Needless to say, Johnny gets the part. That’s The Godfather’s power.

Ironically, it’s the Don’s refusal of an offer that causes things to take a turn. A rival crime boss, Virgil “The Turk” Sollozzo (Al Lettieri), wants the Corleone Family to join him in the drug rackets, but when The Godfather refuses, Sollozzo sends hitmen to kill him. In the aftermath of the attack, Sonny takes over the Family and becomes a war-time Don, seeking council from Vito’s oldest friends, Pete Clemenza (Richard Castellano) and Sal Tessio (Abe Vigoda). Meanwhile, Michael, the one son who wasn’t supposed to get mixed up in the family business, is the one drawn deepest into the fray, vowing revenge upon Sollozzo and his police captain crony (Sterling Hayden).

Ironically, it’s the Don’s refusal of an offer that causes things to take a turn. A rival crime boss, Virgil “The Turk” Sollozzo (Al Lettieri), wants the Corleone Family to join him in the drug rackets, but when The Godfather refuses, Sollozzo sends hitmen to kill him. In the aftermath of the attack, Sonny takes over the Family and becomes a war-time Don, seeking council from Vito’s oldest friends, Pete Clemenza (Richard Castellano) and Sal Tessio (Abe Vigoda). Meanwhile, Michael, the one son who wasn’t supposed to get mixed up in the family business, is the one drawn deepest into the fray, vowing revenge upon Sollozzo and his police captain crony (Sterling Hayden).

Before long, he has blood on his hands and must flee to Sicily. There he’s struck by the “thunderbolt” of the beautiful Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), whom he takes for his bride in a display of love and respect for his Italian heritage. Tragically, a real “thunderbolt” cuts the marriage short — blowing Michael’s love to smithereens.

Before long, he has blood on his hands and must flee to Sicily. There he’s struck by the “thunderbolt” of the beautiful Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), whom he takes for his bride in a display of love and respect for his Italian heritage. Tragically, a real “thunderbolt” cuts the marriage short — blowing Michael’s love to smithereens.

Meanwhile back in the States, New York’s Five Families have “gone to the mats” and are busy mowing each other down. The all-out gang war claims the life of Sonny, who falls for a toll booth trap while on a hot-head revenge mission for his sister.

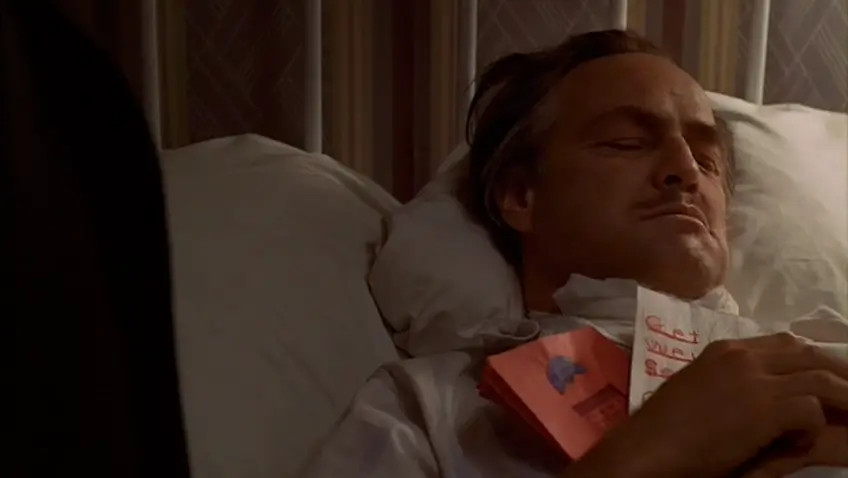

After the death of Sonny, Don Vito decides the violence has gone far enough. He strikes a peace deal with the heads of the Five Families, allowing Michael to return and take over control of the Family.

When Michael returns to the States, his first act is to track down Kay. He asks her to marry him, and they have two kids. After his father’s death, Michael moves to expand the Family out west, encroaching on the territory of Las Vegas pioneer Moe Green (Alex Rocco). Gearing up for the move and fearing assassination by crime boss Don Barzini (Richard Conte), Michael arranges a “meeting” with the heads of the Five Families — a plan to wipe them all out and gain unprecedented power.

Plot Summary (Part II)

Michael’s journey from war hero to vicious killer in the original Godfather sets the stage for The Godfather Part II. The sequel tells two simultaneous tales: the rise of the father, and the fall of the son. In one storyline, we see the journey of Vito (Robert De Niro) from Sicily to Ellis Island; from his petty first crime to his first murder in 1920s New York.

In the other, we pick up where the first film left off, with Michael having taken his family to Nevada, where he, Kay and their children live a life of luxury on Lake Tahoe. That life is shattered one night — the night of their son Anthony’s confirmation — when gunmen target Michael for assassination and shoot up his bedroom.

The attempt fails and Michael realizes there must be a traitor inside the Family. While he tries to figure out the mole, he continues to expand his crime syndicate, meeting with hated Miami rival Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg), whom he suspects gave the assassination order. The two crime bosses feign friendship and do business together in pre-revolution Havana, but both secretly want to do away with the other.

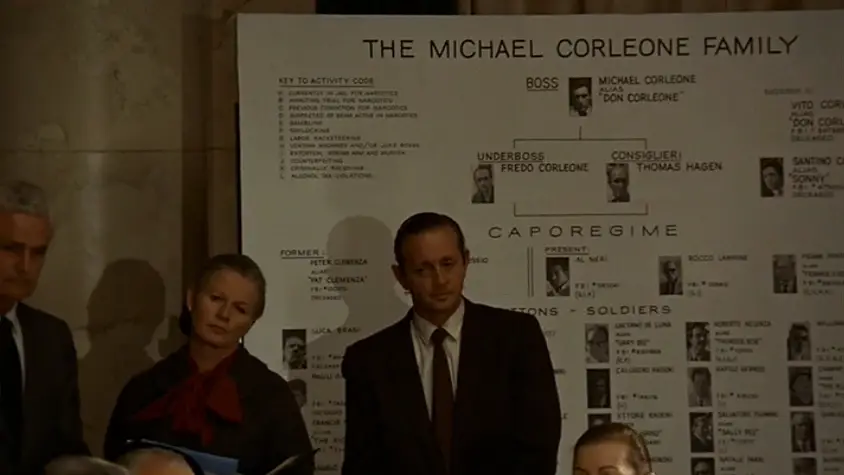

Eventually, Roth outsmarts Michael (and the audience) by staging a fake assassination attempt on a longtime Corleone Family friend, Frankie Pentangeli (Michael V. Gazzo). Believing it was Michael who tried to kill him, Pentangeli becomes an FBI informant and has Michael summoned before a Congressional committee on organized crime. All the while, Michael’s marriage to Kay and his relationship with brother Fredo are falling apart. Soon, he discovers something has happened to him that would never have happened to his father — he’s lost the loyalty of his own family.

One-by-one, Michael destroys those closest to him, sending the film toward its inevitable tragic conclusion, which the BBC called “a shattering act of violence which leaves him unassailable, invincible — and utterly alone.” (G)

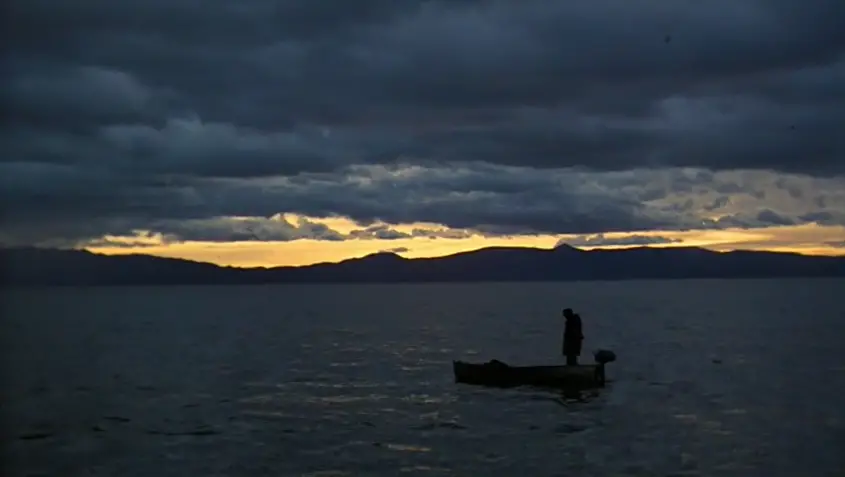

At this point, the Corleone Family is done. As Tom and Frankie lament in a powerful prison scene, the Corleones have suffered the same fate as the Roman Empire. Michael is left to ponder this as he sits alone at his Lake Tahoe estate, weighing the consequences of his actions and recalling better times when his loved ones were still alive.

At this point, the Corleone Family is done. As Tom and Frankie lament in a powerful prison scene, the Corleones have suffered the same fate as the Roman Empire. Michael is left to ponder this as he sits alone at his Lake Tahoe estate, weighing the consequences of his actions and recalling better times when his loved ones were still alive.

History’s Deepest Cast

Between the two films, Coppola was able to compile the deepest cast in movie history. Not only did he resurrect the career of Marlon Brando, he launched the careers of an entire generation of new actors — Al Pacino (Scarface), Robert De Niro (Raging Bull), Diane Keaton (Annie Hall), Robert Duvall (Apocalypse Now), James Caan (Misery), John Cazale (The Deer Hunter), Bruno Kirby (When Harry Met Sally) and Talia Shire (Rocky), Coppola’s own sister. Even Coppola’s daughter, Sofia, the Oscar-winning writer-director of Lost in Translation (2003), appears in Part I as the baby at the baptism (I’m trying desperately to forget her role in Part III). Need more proof of cast depth? The supporting roles are filled by proven talents like John Marley (Faces), Sterling Hayden (Dr. Strangelove) and Lee Strasberg (the famed Actor’s Studio director). Enough said.

How often does a single film earn four Oscar nominations for acting? The Godfather did it handedly with Brando, Pacino, Caan and Duvall. When Brando was the only one to win, it was like the three Corleone boys watching their father show them how it’s done.

Duvall was the perfect cast for Tom Hagen, combining real pathos with evil cunning. His teary-eyed performance at the false news of Vito’s death is topped only by his cracking voice as he breaks the news of Sonny’s death to Vito. The film earned Duvall his first of six career nominations, earning another with Coppola in Apocalypse Now (1979) and setting up his eventual win for Tender Mercies (1983).

It was also the first and last nomination for Caan, who was fresh off his role as an ill-fated football star in the TV movie Brian’s Song (1971). The studio execs initially wanted Caan to read for Michael, having fingered Burt Reynolds for Sonny, but both Brando and Coppola fought hard for Caan. Needless to say, they got the right Sonny.

Oscar also shut his door on Diane Keaton, who did not earn a nomination for either of the two films. No matter, she was busy with Woody Allen, starring the same year in Play it Again, Sam (1972) and soon winning an Oscar for Annie Hall (1977). While the Allen films brought out her best work, it’s a thrill to watch Keaton here, young and wounded against the equally fresh Pacino. Together, the two are fireworks.

Part II only upped the Oscar ante, earning five acting nods — Pacino, De Niro (who won), Strasberg, Shire and Gazzo. Good for Gazzo, whose character was invented at the last minute to replace Clemenza, after Richard Castellano held out for more money and forced Coppola to whack him from the script. What a shame, too, because the idea of Clemenza committing suicide in a bathtub like the fallen Roman Empire would have brilliantly paralleled the scene where a Young Clemenza launches the Corleone Family by handing Young Vito his first guns, examined in a tiny apartment bathtub.

Brando and DeNiro: Two Oscars, One Role

Time after time, Coppola stood his ground on casting decisions. He knew who he wanted, and he got them. When casting the title role, Paramount had originally wanted Orson Welles, Burt Lancaster, George C. Scott or Edward G. Robinson, but Coppola insisted upon either Brando or Laurence Olivier. When Olivier was unavailable, Coppola went with Brando, who hadn’t had a hit movie in a dozen years. (G) The result was not just another great role for Brando, but the iconic role of his career.

It’s one of those instantly imitable performances, where fans can brush their cheek and emulate that scratchy voice. Brando says he wanted the character to look “like a bulldog,” so he stuffed his mouth with cotton swabs for the screen test and special mouth gear was designed for the actual shoot. (F) The effect is unforgettable, though it makes him sound like he’s got a mouth full of mush. Subtitles, anyone?

Vito Corleone was recently voted Premiere magazine’s #1 Greatest Movie Character of All Time — a testament to Brando’s ability to become the character. He is not acting. He is being. And his performance is best on display in the aftermath of Sonny’s death. Watch how he juggles his emotions with his crime boss duties, walking the line of “it’s not personal, it’s strictly business.” But how do you do that when it’s your own son?

The performance was good enough for Brando’s second Oscar. But following the tradition of George C. Scott (Patton) the year before, Brando refused to accept the award. Instead, he sent an Apache woman named “Sacheen Littlefeather” to protest the negative treatment of Native Americans in the film industry. Turns out was she wasn’t a Native American at all, but rather a B-movie actress. (G) The bizarre moment doesn’t diminish Brando’s performance. In a weird way, it heightens its mystique.

As for De Niro, who had burst onto the scene just a year earlier in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), his Oscar win for Godfather II launched him to Hollywood’s A-list. As Coppola accepted the award on DeNiro’s behalf, he said, “I think Robert De Niro is an extraordinary actor and he is going to enrich films that are made for years to come.” While no one could have matched Brando’s performance, De Niro makes a valiant effort, using the same Method acting Brando made famous. Just as Brando had to become his mafia Don, De Niro had to become Brando’s version of the same man. He did his best to apply that signature scratchy voice, but his best moments come when he doesn’t say a thing, like his concerned look as he watches baby Fredo with pneumonia. To this day, Brando and De Niro remain the only two to win an Oscar playing the same character.

Al Pacino: Made Man

As for Pacino, it’s a performance different from what today’s Pacino fans are used to. He is not the over-the-top caricature of Scarface (1983), and his voice has not yet developed the rasp of Any Given Sunday (1999). Rather, his performance is quiet and restrained, but never once safe. Beneath Pacino’s calm, there’s always the threat of an outburst: “Enough!” “In my home!” “Can’t you give me a straight answer anymore?!?”

Coppola claims he saw Pacino’s face the moment he read Puzo’s book, even though Paramount claimed he was too short and understated. (D) The studio desperately wanted Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson or Dustin Hoffman, but Coppola stuck to his guns with the no-name Pacino. (G) He knew he was sitting on an undiscovered megastar.

Pacino himself called it the most difficult role he’s ever played, because “Michael never thought of himself as a gangster, ever. Not as a child, not while he was one, and not afterward. That was not the image he had of himself.” (D) Thus, Pacino had to play a man who becomes something he insists he isn’t and never wanted to be. The fact that he had to wait 20 years until Scent of a Woman (1992) to win the Oscar is a joke. His twice-nominated work as Michael Corleone should have won it easy, especially in Part II.

“Pacino’s work in the middle film of Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy is the gravest of the greatest leading performances on film,” wrote Premiere magazine, who ranked it the #20 Best Performance of All Time. “The hollow-eyed Pacino wins our empathy even as he wreaks evil.” (D)

Acting across Strasberg, his own Actor’s Studio mentor, Pacino gives a lesson in subtle facade. When he discovers his family betrayer at a Havana entertainment show, he drops his head in a truly heartbreaking moment. When he kisses his betrayer like Judas, we see the disappointment in his eyes. When Kay reveals a family secret, we see the fury slowly building in his eyes. And when he stares off coldly at the end, we can’t help but wonder what haunting images are running through his head.

Still, Pacino’s own favorite moment came in the first film. It wasn’t his darting eyes before his first hit; nor the steadiness of his hand outside the hospital. It wasn’t his hypocritical face at the baptism; nor his lying eyes to Kay at the end. For him, it was that slow walk across the street after the film’s final murder, purging a family outsider.

“Pacino was everything I wanted that character to be on screen,” Mario Puzo writes in The Godfather Papers. “I couldn’t believe it. It was, in my eyes, a perfect performance, a work of art.” (D)

Screenplay: Structure, Character, Dialogue

After selling 10 million copies, The Godfather novel already had the skeleton of a great story. It would be up to Coppola, co-writing with Puzo, to bring that story to life. The WGA recently voted The Godfather the #2 greatest screenplay of all time, behind only Casablanca (1942). And to prove it was no novel-based fluke, Coppola and Puzo invented an entire sequel, imagining the backstory for Vito, while debating whether Michael would actually whack a family member. The parallel storyline structure is a revelation. What a genius idea to show a father’s story side-by-side with his son! The WGA voted the sequel #10 greatest script of all time. That’s two of the Top 10.

The greatest accomplishment of both scripts may be how they get us to root for a group of killers. They do so by establishing a unique “moral universe,” their script’s very own “ordinary world.” In their world of gangster mores, they’re the good guys, and Vito is the figure of ultimate justice. When Sollozzo wants to expand organized crime into narcotics, Vito refuses, saying, “Drugs is a dirty business.” When Bonasera asks him to kill the men who brutalized his daughter, Vito claims murder would not be just, because they didn’t actually kill her. And when the heads of the Five Families gather to arrange a ceasefire, Vito swears on the souls of his grandchildren that he’s not going to be the one to break the peace.

Vito’s “morality” is what makes us sad to see him go, and his positive reputation sets up the real tragedy of Michael. For the second half of Part I and all of Part II, the point of the story becomes just how far Michael has fallen. It’s one of cinema’s best examples of character growth, in this case, negative growth. His moment of truth is legendary, sitting at a public restaurant with a gun in his pocket, debating whether he can go through with murder; whether he can live like his father. His choice becomes all the more tragic as we see just how much Michael becomes unlike his father, despite that being his deepest desire. Compared to Vito’s version of a “meeting with the heads of the Five Families,” Michael’s bloody definition is horrific.

Still, Michael is the AFI’s #11 Villain of All Time not because he kills people, but because he lies about it to his wife. After promising Kay in the first film, “In five years, the Corleone Family will be completely legitimate,” Kay reminds him at the start of the second film, “That was seven years ago.” Hollywood script doctor Dara Marks called this fatal flaw “a survival system that has outlived its usefulness,” describing Michael as a man yearning independence (“I have my own plans for my future”), while craving interdependence with others (“Can you lose your family?”). Critic Pauline Kael called it “the divided spirit of a man whose calculations often go against his inclinations.” (D)

On top of such masterful character development, the scripts feature some of the most quotable dialogue in movie history: “It isn’t personal. It’s strictly business.” “Don’t ever take sides with anyone against the family again.” “You know who I am? I’m Moe Green. I made my bones when you were going out with cheerleaders.” “If one thing is certain, if history’s taught us anything, it’s that you can kill anybody.”

“It’s just unbelievable the way people talk about it and the way people remember every little thing and can recite the dialogue,” Julia Roberts told the AFI. (H)

Seven quotes from the trilogy made the ballot for the AFI’s Top 100 Movie Quotes, including, “Leave the gun. Take the cannolis;” “It’s a Sicilian message. It means Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes;” “I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart. You broke my heart;” “Michael, we’re bigger than U.S. Steel;” and “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!”

Two quotes made the final list. Ranking at #58, three spots ahead of Pacino’s own “Say hello to my little friend,” is Michael’s advice regarding Hyman Roth: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.” Ranking all the way at #2, a spot ahead of Brando’s own “I coulda been a contender” speech, is the film’s most legendary line: “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

Accessibility Issues

For all their complexity, the screenplays can be an accessibility struggle for some first-time viewers. First-time viewers may have a hard time understanding who’s getting whacked and why, thanks to mushy-mouthed dialogue by Brando, scratchy-voiced dialogue by Pentangeli, and a serious string of double and triple crosses, particularly in Part II when a hitman says, “Michael Corleone says hi!” However, if you go back and watch the films again, I promise, it’s all accounted for, every “i” dotted, every “t” crossed.

Both scripts also take their time in set-up, knowing they have three hours to tell their tales. This makes for longer Act Ones than many are accustomed to. In Part I, viewers have to endure 30 minutes of the wedding scene before the first major piece of action (horse head in the bed) and 45 minutes before the turning point (the shooting of The Don). While viewers do get two murders in the first 5 minutes of Part II, they then have to wait another half hour before the bullets come flying through Michael’s bedroom. This wouldn’t be a challenge, except for the fact that both extended openings feature slow-taking Dons holding business meetings in dimly-lit offices.

Such complaints are less the fault of the screenplays and more a result of our society’s fleeting attention span. Rarely, do we see three-hour films anymore, let alone films that ask us to engage this much. It’s a sad phenomenon, yet one I fear is hear to stay with the advent of the 140-character response. Thus, The Godfather films should carry a disclaimer when you watch them for the first time. Don’t expect to scarf these things down. Treat them like a juicy steak and a fine bottle of Coppola wine. Savor them. Ponder the aftertaste. And realize length and complexity is a small price to pay for this type of scope and substance.

Scope and substance. This was Coppola’s mission. From the minute he walked onto the project, he fought to increase the budget and transform The Godfather from a cheap gangster thriller into an epic saga. (G) Cinema had long seen the rags-to-riches gangster film, from The Public Enemy (1931) to Little Caesar (1931) to Scarface (1932). What Coppola wanted to explore was the white collar mafia, a top-down treatment that allowed him to examine our world’s most powerful themes of corruption.

Coppola & The Hollywood Renaissance

Arriving the same year as Hitchcock’s final great film, The Godfather marked a pivotal point in the filmmaking continuum of the 20th Century. Coppola both understands the masters of the past and embraces the flair of the 1970s Hollywood Renaissance. On the one hand, he wrote the word “Hitchcockian” in the margins of his Directing Bible for influence in directing Michael’s hospital visit. On the other, he upped the ante on Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), using 149 “squibs” in Sonny’s toll booth massacre and having Carlo’s foot fly through a windshield to wipe the camera in a ballsy hood-mount. (F)

Paramount executive Robert Evans had no incentive to take chance on Coppola, who despite writing the Oscar-winning script for Patton (1970), had bombed with his last three directorial efforts. Fastforward to Oscar night 1973, and The Godfather had made Coppola the favorite to win Best Director. When he was upset by Bob Fosse for Cabaret (1972), Fosse joked, “You’re letting me stand up here because Coppola or Mankiewicz hasn’t shown up yet.” Coppola got the last laugh when he won two years later for The Godfather Part II, saying, “I almost won this a few years ago for the first half of the same picture.” (G)

Coppola understood as well as anyone how to weave visionary directing concepts into universal themes. The question becomes not what themes are explored in The Godfather, but what themes aren’t explored in The Godfather? And with each theme presented, each hypothesis posed, Coppola finds a masterfully artistic way of expressing the idea. They say Apocalypse Now (1979) drained his talents somewhere in Vietnam, but man, in his prime, Coppola’s directing prowess was unrivaled. If his star burnt out quick, his meteor left an indelible mark on the way we make movies.

“The Godfather is the best filmmaking ever in the history of American cinema,” said Apocalypse Now star Martin Sheen. “There is nothing that speaks more to who we are, where we came from, what we stand for, and where we’re gonna go. That’s the work of a true genius.” (H)

The Puppetmaster

Like all the best filmmakers, the analysis of directorial themes begins right at the opening credits. The Godfather‘s marionette logo serves as our first clue as to what the film’s about: seeking a position of power where you hold all the strings.

The marionette theme reappears in Part II in the scene where Vito brings his family to Sicily for the first time. As Vito holds Young Michael on a moving train, he tells Michael to wave goodbye and he holds his little hand like a puppetmaster. It appears yet again after Vito commits his first murder, joining his family on a Little Italy stoop and controlling Michael’s tiny hand, saying, “Your father loves you very much.” Finally, Coppola comes straight out and mentions it in dialogue in the patio scene just before Vito’s death, a scene actually written by Robert Towne (Chinatown):

VITO: I never wanted this for you. I work my whole life — I don’t apologize — to take care of my family, and I refused to be a fool, dancing on the string held by all those bigshots. I don’t apologize — that’s my life — but I thought that, that when it was your time, that you would be the one to hold the strings. Senator Corleone; Governor Corleone. … Wasn’t enough time, Michael. Wasn’t enough time.

Fatherhood and Family

The puppetmaster motif serves to set up an even larger theme: that of fatherhood and family. Vito knows he is setting his children up for a life of crime, just as sure as Sonny’s infancy taking place on a stolen rug. As Puzo wrote for Brando in Superman (1978): “The son becomes the father, and the father the son.”

The tragedy is that Michael is the one son Vito does not want to live the life of crime, yet he is the one who enters it most forcefully. Upon learning Michael has committed his first murder, Vito tears up and turns his head.

Michael’s turn as father is even worse, as his relationship with his own son, Anthony, is almost non-existent. Michael can’t find the time to enjoy a hand-drawn picture from Anthony, because bullets come flying through the window. When the boy asks if he can join his father on his next trip, Michael declines. Is it any wonder that Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s in the Cradle” arrived the same year?

Michael is so busy expanding his empire that he has to ask Tom what they got Anthony for Christmas — a toy car. Later, when Michael returns home to find that same toy covered in snow, Coppola shoots him through the symbolic window of Michael’s business office. It’s a sad reminder that this man has worked so hard toward preserving his family, yet in doing so he has destroyed it. When Kay raises the issue at the Hotel Washington, all Michael can say is, “I don’t wanna hear about it!” Deep down he knows he has forsaken the advice of the very man he’s tried to emulate, his father, who insists: “A man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man.”

His failings as a father are at the core of the scene where he asks his mother if it’s possible to lose your family. Family. A good drinking game would be to take a shot every time the word is mentioned, between the Corleone family unit and the Corleone Crime Family. They sit around the family dinner table. They deal with the heads of the Five Families. And Michael warns his brother to “Never turn your back on the Family again.”

This idea of “family” is what makes the end of Part II so tragic. After Michael commits the ultimate sin, a flashback shows the family sitting around the dinner table waiting for Vito’s surprise birthday party. Looking around the table, we realize that four of the guests have now been killed. We cringe as Sonny’s kids say, “Daddy’s fighting again,” knowing it’s his temper that destroys him. We wince as Tom describes high hopes for Michael’s future, knowing what his future has become. And we choke up as Fredo, of all people, is the only one who reaches out to defend Michael. It’s all so sad.

Masculinity & The Patriarchal Society

While the men meditate on their roles as fathers, what becomes of the women? As much as anything, The Godfather films are Coppola’s commentary on the patriarchial society we live in, heightened by the norms of the mid-20th century, and through it, exposes its many flaws. We see only “Godfathers,” not godmothers. When Luca Brasi wishes the best for Connie, he says, “May their first child, be a masculine child.” When Vito asks Michael about his family on the patio, he asks, “How’s your boy?” And when Michael screams at Tom to tell him about his unborn child, he only cares about one thing: “Was it a boy?!”

Each male character has his own twisted take on what it means to be a man. For Vito, it means hiding your emotions. When Johnny cries, Vito soundly rebukes him: “You can act like a man! What’s the matter with you? Is this how you turn out? A Hollywood finocchio that cries like a woman?”

For Carlo, it means you can beat your wife and she has to take it. The scene of him whipping Connie is one of the hardest to watch in movies.

For Sonny, it means the ability to cheat on your wife and get away with it. There’s a brillaint shot where Sonny’s wife describes the size of his manhood, and in the background, we actually see Sonny leaving with one of the bridesmaids. Here, Coppola uses the entire depth of field to comment on his theme.

For Sonny, it means the ability to cheat on your wife and get away with it. There’s a brillaint shot where Sonny’s wife describes the size of his manhood, and in the background, we actually see Sonny leaving with one of the bridesmaids. Here, Coppola uses the entire depth of field to comment on his theme.

Finally, for Michael, it means putting business before your woman. His leaving Kay at the dinner table with a glass half full of wine is only the start of it.

Think about it. He goes off to Sicily without contacting her, then pops back into her life to propose. She spends the rest of the film, and the sequel, locked up inside the Corleone compounds. Coppola foreshadows this in Part I, showing Kay behind the jail bars of the Corleone gates. When Kay is stopped at the Lake Tahoe gates in Part II, she fittingly wears a pinstriped outfit to echo her own jailed existence.

Think about it. He goes off to Sicily without contacting her, then pops back into her life to propose. She spends the rest of the film, and the sequel, locked up inside the Corleone compounds. Coppola foreshadows this in Part I, showing Kay behind the jail bars of the Corleone gates. When Kay is stopped at the Lake Tahoe gates in Part II, she fittingly wears a pinstriped outfit to echo her own jailed existence.

The most egregious moment comes at the end of Part I. After saying, “Don’t ask me about my business, Kay,” Michael lies to her face when she presses him about Carlo’s death. Perhaps it’s the notion of keeping “business” separate from “personal.” Or, perhaps he’s echoing his father’s philosophy: “Women and children can be careless, but not men.” Either way, the final shot drives home the theme of chauvinism, as Michael’s henchmen literally close the door on Kay. The act is repeated twice in Part II, first as Vito closes the door on his wife after receiving the stash of guns, then as Michael catches Kay overstaying her visit with their kids. The closing door is the ultimate symbol of the male attempt to shut women out, and Shire said she always felt that was the most violent act in the film.

But does Kay actually finish with the upper hand? It is she who takes the relationship into her own hands and stands up to Michael, even if she has to get slapped in the face for it. Talk about “women’s right to choose.” It may be a brutal scene, but Kay is the victor.

Religious Hypocrisy

Kay’s discussion of “something evil and unholy” is but one of the countless religious elements of The Godfather — as one might expect from a group of Roman Catholic mobsters. If the title isn’t your first clue, then the Part III plot of a corrupt Vatican is proof of the film’s metaphor between organized religion and organized crime.

Is Coppola completely skeptical of religion? Who am I to say? But whether you’re a Christian or not, everyone can appreciate Coppola’s artful attempt to separate the true meaning of Christ (love, charity, good will) from the horrors that mankind has committed in his name (Crusades, Holocausts, Mafias).

The most obvious example is the intercutting of baptism and murder at the end of Part I, as Michael becomes a godfather in two senses. In textbook parallel action, the sequence juxtaposes (a) shots of Michael calmly denouncing Satan, with (b) shots of the brutal murders he has authorized. How many hypocrites have done this throughout history?

Still, to me, the most powerful religious statement is one I’ve never seen disected — until now. It comes in Part II, when a frowning Christ madonna — covered in money — is carried through the streets of Little Italy in a Roman Catholic parade. As the camera tracks down the street, portions of the madonna are blocked by street-side stands, revealing (a) only Jesus, or (b) only money. Note also that a row of “temptation” apples hangs over the “all money” image — the very part shown when Fanucci crosses himself. It’s an absolutely genius piece of mise-en-scene.

Political Corruption

If religion can be corrupted, than politics certainly can. In Part I, Sollozzo asks Don Vito to lend him “those politicans you carry in your pocket like so many nickels and dimes.” This is reinforced when Tom warns Sonny, “Even the old man’s political protection would run for cover!” How serious a problem is this? Are politicans really at the mercy of the mob? The debate plays out horrifically in a conversation between Michael and Kay:

MICHAEL: My father is no different than any other powerful man.

KAY: You know how naive you sound? Senators and presidents don’t have men killed.

MICHAEL: Oh? Who’s being naive, Kay?

Still, for some reason, politicians represent a more honest way of life to Vito. He admits they’re corrupted, but he wishes the politician’s life upon Michael more than mafioso. “I never wanted this for you,” he says. “I thought that when it was your time that you would be the one to hold the strings. Senator Corleone, Governor Corleone, something.” Michael responds with the pejorative term: “Another pezzonovante.”

While this is about the extent of political talk in Part I, Part II personifies the theme in the character of Senator Pat Geary (G.D. Spradlin). He’s a shmuck who can’t even remember the names of the people he’s honoring with an award. He calls Kay by his own name, “Pat,” and mispronounces their last name as “Cor-lee-ahn.” Moments later, he tries to muscle Michael over a casino license (“I intend to squeeze you”), but oh how easily he is manipulated by the mob. After the Corleones massacre a poor young floozy and pin it on a drunk Senator Geary, he is putty in their hands.

All it takes it to expose his flaw (philandering) and before you know it, he’s drinking cocktails in Havana with the biggest crime bosses in North America. Which brings us to the biggest political aspect of Part II — how its midpoint is set against the backdrop of the Cuban Revolution and the fall of President Batista on New Year’s Eve 1958. As Michael rides through the streets of Havana en route to a meeting, he witnesses a member of Castro’s insurgency jump into a car with a bomb strapped to him, taking a police captain with him. Moments later, Michael has an epiphany that seems like something out of The Battle of Algiers (1966): “It occured to me. Soldiers are paid to fight; rebels aren’t. It means they could win.” Draw your own parallels to Vietnam, Iraq and countless other conflicts.

Corruption of Justice

From politics to the justice system, The Godfather is an equal opportunity watchdog. For one, there’s the whole notion of a Tom Hagen lawyer assigned to defend the Corleone Family in legal matters. There’s also the corrupt Police Captain McClusky who’s on Sollozzo’s payroll and looks the other way while men come to kill Vito. Finally, there’s the Congressional hearings on organized crime, where justice is the last thing served.

While Hyman Roth plants his own man on the committee to screw Michael, Michael returns serve by using an old Italian custom to manipulate the chief witness. The evidence is thrown out, the committee chairman is left scratching his head and Tom Hagen demands an apology.

Corruption of Entertainment

The films also deal with the corruption of the entertainment industry. Look no further than the allusion to Frank Sinatra that is Johnny Fontaine. We’re shocked to learn how Johnny got his singing career: “Luca Brasi put a gun to [the bandleader’s] head and said, ‘Either your brains or your signature will be on the contract.'”

With his singing career in place, Johnny then looks to the movies, having The Godfather strong-arm a “Hollywood big shot” to give him a coveted film role. That big shot is Jack Woltz, who is adamant that “Johnny Fontaine doesn’t get that movie!” That is until the famous horse-head scene, where Coppola places an Oscar statue on Woltz’s nightstand. Note the flowers that Johnny sends as a thank you to the Don when he gets the part.

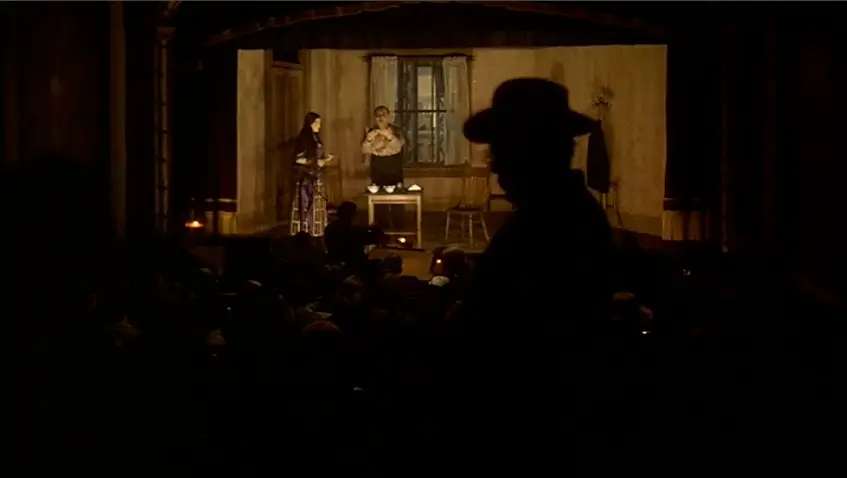

In Part II, Hyman Roth is kind enough to remind us of the corruption of sports, saying he’s liked baseball ever since Chicago threw the World Series in 1919. In Havana, Fredo’s connection to Roth is established against the backdrop of a Cuban nightclub show. And in the Little Italy flashback, Fannuci appears to have leverage of an Italian opera singer. The shot of his silhouette passing the stage is quite disturbing.

Business Corruption

But alas, sports and entertainment are merely big business, and corrupt businesses pervades The Godfather. In this world, what’s right for “business” is bigger than life and death. Even after his beloved father is gunned down, Tom says the attack was “business, not personal.” Hyman Roth recognizes the same gangster code. He describes his sadness that Moe Green does not even have a plaque in the town he invented (Las Vegas) because he was murdered. Knowing full well it was Michael who had him killed, Roth looks at Mike and says, “No one knows who gave the order. When I heard it, I wasn’t angry. … When he turned up dead, I let it go. And I said to myself, ‘This is the business we’ve chosen!’ I didn’t ask who gave the order, because it had nothing to do with business!”

The entrepreneurship of crime is shrewd, and it’s fascinating to hear things like heroin discussed in a capitalist business model:

TOM: There’s more money potential in narcotics than anything else we’re looking at. Now if we don’t get into it, somebody else will, maybe one Five Families, maybe all of them. Now with the money they earn, they can buy more police and political power, then they come after us. Now we have the unions, we have the gambling, they’re the best things to have, but narcotics is the thing of the future. If we don’t get a piece of that action, we risk everything we have. Not now, but 10 years from now.

While The Don takes a moral stance against expanding into the drug trade, Michael jumps at the chance to spread his empire into the Carribean. It pays off, as Roth commends their success: “Michael, we’re bigger than U.S. Steel.” The most poignant image of the entire Roth-Corleone partnership comes during Roth’s birthday party, where a cake decorated with an image of Cuba is symbolically sliced into pieces and passed out. All the while, Roth describes his wishes to divy up his Cuban assests.

Michael is also invited by President Batista to a meeting of the hemisphere’s biggest moguls, representing sugar, produce, tourism, mining and telecommunications. It’s at least a partial nod to the 1946 Havana Conference, where American mafia met with Cosa Nostra leaders. Such international mob connections are fodder for conspiracy theorists who believe the assassination of JFK was deal between the mafia and Fidel Castro.

Conspiracies aside, we gravitate toward The Godfather because it makes no bones about what life really is — one giant power grab. Call them greedy, but these men are ambitious entrepreneurs. Vito’s desire to “hold the strings” shows his realization that those at the top get to call the shots, while those at the bottom get stepped on.

The American Dream Perverted

Vito’s quest for power represents the dark side of an otherwise inspiring American Dream. Let’s not forget the first line of the saga is Bonasera’s: “I believe in America.” This statement, spoken in thick accent by a proud Italian American, shows the strong immigrant spirit that helped build our melting pot. Vito’s assimilation begins in the streets of Little Italy, where he befriends Tessio and Clemenza, who help him form the olive oil company GENCO. The group imports its oil from Don Tommasino, who helped Vito escape Sicily as a boy and helps him return as an adult to seek bloody revenge.

Indeed, a lot changes between Vito’s boyhood and adulthood. Compare his view of the Statue of Liberty at both stages in life. At the start of Part II, Coppola provides a sweeping shot of Young Vito and his fellow immigrants staring in wonder at the promise of Lady Liberty as the ship pulls into New York Harbor. Coppola romanticizes what it must have been like for those brave people landing on the shores of Ellis Island.

By the time Vito reaches adulthood, however, Coppola shows Lady Liberty in a colder light. As Clemenza whacks Paulie in the Meadowlands, the statue stands far in the distance, a symbol of the American Dream run amok. The reality is much harsher than the romanticized ideal, thus Vito learns to manipulate the system, prostitute its promise, create his own empire of violent capitalism, and do it in the name of the Old Country.

This adds another layer to the conversation as Tom and Frankie compare the Corleone Family to the Roman Empire. Are they not also comparing it to the American Empire? Isn’t the Corleone Family itself teetering on the brink of collapse if it continues down its current path of corruption and ethnocentrism? The comparison to the Romans is both a fitting historical reference and an ode to the film’s Italian heritage.

Which brings us full circle back to the dangers of family/national legacy. Kay exposes it when she says, “I knew you could never forgive me, Michael. Not with this Sicilian thing that’s been going on for hundreds of years!” Coppola, a proud Italian American himself, actually received backlash for his portrayal of Italian Americans as criminals. He answered the criticism with this speech in Part II:

Senator Geary: These hearings on the Mafia are in no way whatsoever a slur upon the great Italian people. Because I can state from my own knowledge and experience that Italian Americans are among the most loyal, most law-abiding, patriotic, hard-working American citizens in this land. And it would be a shame, Mr. Chairman, if we allowed a few rotten apples to give a bad name to the whole barrel.

Dangerous Oranges

The real “rotten apples” are what I like to call Coppola’s “dangerous oranges.” Throughout the films, Coppola uses a motif of specially-placed oranges to signal coming danger. The Don kicks over a basket of oranges when he’s attacked by Sollozzo’s men. Fanucci tosses an orange during his final stroll through Little Italy. Clemenza grabs a pitcher of wine with floating oranges as he tells Paulie to go do his job, then later kills Paulie for not doing his job. Tessio reaches across Mama Corleone to grab an orange during the wedding, literally crossing the Corleone Family, which later has him killed.

Johnny Ola brings an orange to Michael, who seems hip to the motif and flips it, saying Johnny and his men look hungry — then killing them. There’s a bowl of oranges on the table when Woltz turns down Johnny’s role in the film, leading to the famous horse head scene. A bowl of oranges also sits on the table during the meeting of the Five Familes, where the Don literally reaches out to shield the oranges between he and Barzini as he stands up to make the peace. Finally, the Don puts orange pieces in his mouth to scare his grandson just moments before he drops dead in the garden.

Fittingly, Coppola closes the saga by having a Michael drop an orange the minute he drops dead in Part III.

Foreshadowing in Mise-en-Scene

The oranges are just some of many examples of Coppola’s mastery of mise-en-scene, or in laymen’s terms, the symbolic placement of all elements in the frame. In Part I, Coppola shows a fish pattern on the bar window where Luca Brasi is strangled, foreshadowing the scene where Sonny receives a Sicilian message: “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes.”

My favorite bit of mise-en-scene comes in Part II in the form of Fredo’s bad omen, which fate had been building since Part I, when Michael told him, “Never take sides against the family again.” In the Lake Tahoe scene where Michael tells Fredo, “You’re nothing to me now,” check out the row of life rafts outside the window. Across the left of the frame, where Michael sits, there are plenty of rafts (safety), but to the right, behind Fredo, there are none (danger). These particular rafts take on even more significance when you consider where Fredo ends up at the end of the movie.

Transitions & Parallelism

The ultimate foreshadowing is, of course, Young Vito’s life predicting Michael’s. The parallel tales of Part II allow for some very clever transitions moving from Vito’s story to Michael’s, and vice versa. These moments, separated by time, are still connected by fate.

At one point, Coppola cuts from Vito’s line “Michael, say goodbye,” to Mama Corleone’s funeral where Michael literally “says goodbye.” At another, he dissolves from Michael to Vito, their hands positioned exactly the same as they cope with their infants’ mortality.

Such brilliant parallelism pervades the films. We go from opening Part I with a slow pull-back to reveal Vito sitting at his desk, to opening Part II with Michael seated at that same desk. We go from Michael pulling out a specially-placed gun for his first murder in a bathroom, to Vito doing the same for his first murder on a rooftop. We go from Michael’s murder montage at the end of Part I to his murder montage at the end of Part II. And we go from Vito handling his first guns in his apartment bathtub, to Frankie slitting his wrists in a bathtub — a fate originally intended for Clemenza. Screw Castellano for not returning as Clemenza. He ruined one of Coppola’s most genius parallels.

Michael Off the Rails

One almost gets the sense that all of these parallels — spelling the rise and fall of the Corleone Family — flash before Michael’s eyes in the seconds before he commits his first murder. With a slow push-in on Michael’s face, Coppola takes us deep into Michael’s head. A faint red filter flashes over Michael’s face as he darts his eyes around, while the sound of an elevated train screeches down the tracks.

Is Michael remembering the Sicilian train ride with his father, shown moving right-to-left in Part II? Or, is fate foreshadowing the oil painting of a train moving right-to-left as Vito ends the very gang war sparked by the murder Michael is about to commit?

Gordon Willis: Prince of Darkness

Much of the film’s power is due to Coppola’s right-hand man, cinematographer Gordon Willis, who provides one of the most talked-about lighting jobs in history. With daring overhead lighting and experiments in overexposure, Willis creates what critic David Thomson called a “bold exploration of film noir in color.” (B) Unfortunately he was never quite appreciated in his day, snubbed for nominations in both Godfather I and II, and receiving only two nominations in his career: Zelig (1983) and The Godfather Part III (1990). The Academy made it up to him with a Lifetime Achievement Award the same year as Roger Corman, who had launched Coppola’s career.

Willis’ contribution can not be understated. How intimidating would Brando be without those overhead lights creating hollow, raccoon shadows around his eyes?

How much suspense would be lost if it weren’t for the flickering lightbulb as Vito prepares to shoot Fanucci?

And how quick would we forget the duality of good and evil if it weren’t for the half-lit faces, like that of the corrupt Capt. McCluskey as he breaks Mike’s jaw?

Half-lit faces continue throughout. Check out the lying Michael as he tricks Carlo into indicting himself in Santino’s murder.

Also note Michael as he tells Tom how to pursue the Family’s “inside” betrayer.

Michael is almost fully in the dark as he tells his mother his fears of losing his family.

Finally, look how he’s left in half light as he ponders the consequences of his actions.

Art Department

Working hand-in-hand with Godon Willis’ sepia tones are some of the most ambitious period visuals ever attempted. Part I covers ’40s New York, Hollywood, Sicily and Las Vegas, but is rather minimal in the exteriors it shows. With a bigger budget for Part II, Coppola goes bigger, recreating not only ’50s Nevada and Miami, but also ’50s Cuba (shot in the Dominican Republic), 1901 Ellis Island, 1907 Sicily and 1920s New York.

The entire art department fires on all cylinders. The costume department provides sharp three-piece suits. The effects department places countless blood-squirting electrical charges. And the makeup department creates Mike’s broken jaw with foam latex.

Even the smallest, most insignificant props are symbolically placed, from the knife in Vito’s hand when Fanucci enters the fruit shop, to the model cannon Senator Geary turns toward Michael during their initial meeting.

Last but not least, I know you’re wondering about that horse head in the bed. During rehearsals, a false head was used, but for the actual shoot, Coppola snuck in a real one, eliciting a bigger reaction from actor John Marley. Not to worry. No animals were harmed in the making of this movie. The head was borrowed from a dog-food factory. (F)

Soundtrack

If the look of The Godfather ensures authenticity, its sound solidifies its ability to haunt. Composer Nino Rota was already well known for his work in Italy with the great Federico Fellini, and his scores for La Dolce Vita (1960) and 8 1/2 (1963) remain some of the finest in movie history. Coppola was blown away when he sat down with the master Rota to hear what he’d been working on.

Rota had topped himself with a score that would become his lasting legacy. The AFI voted The Godfather score the #5 Greatest Film Score of All Time. It consists of three main pieces: the “Main Theme,” the “Love Theme” and “Michael’s Theme.”

The wailing trumpets of the “Main Theme” are the most recognizable and the most haunting, particularly in the moments of silence between the notes. When the trumpet switches over to the mandolin and vibrating brass, we can’t help but get sucked in. Part of the joy of The Godfather is watching this theme pop up in various forms: sung in Italian by a boyhood Vito, played on a church organ at Anthony’s confirmation, and sung by an Italian guitarist on the front stoop of Little Italy.

“The Love Theme” works both epically with an entire orchestra of violins and minimistically on a single mandolin. It became the hit song “Speak Softly Love” by Al Martino, and is the theme that Tony Kornheiser once joked should be played all around us at every second of every day. (C)

“Michael’s Theme” is easily the most sadistic. Its strings carry us into the end credits of each film. Its trumpets warn Michael as he makes his way through the empty hospital to aid his father.

In addition to Rota, Coppola refused to “go against the family” and employed his father, Carmine, who provides the music for the mafia war montage in Part I, where he appears on screen as a piano player. Together, the two shared an Oscar for Part II, which features the beautiful “Immigrant Theme.” How can one not get the chills when the strings kick in at 0:30? Carmine was so excited to win an Oscar that he dropped and broke his statue on the way back to his seat.

The music is instantly recognizable whenever it’s played, sending the crowd in a frenzy when Slash broke it out on his electric guitar at a Guns N Roses concert.

Pop Culture

The Guns and Roses reference is just one piece in the Godfather pop culture pie. Everything we think we know about mob terminology comes from The Godfather, from “sleeping with the fishes” (a dead body in a river) to “going to the mats” (sleeping on warehouse mattresses during a time of mob war) to “making an offer he can’t refuse” (persuading by any means necessary). This has led to a least a dozen references on The Sopranos, including an episode where the boys bootleg Godfather videos:

The film has also left its mark on our politics. From Republican candidate Herman Cain’s Godfather’s Pizza company, to President Obama’s own Brando impersonation during the 2008 campaign:

Homages are constantly made in other films, including The Freshman (1990), In the Name of the Father (1993), The Departed (2006) and Analyze This (1999).

Many times we see the spoofs before we even know their source. This was likely the case for many young Adam Sandler fans watching Billy Madison (1995):

You can also flip through television and find it referenced constantly, including The Simpsons, The King of Queens, That 70s Show and “The Bobfather” spoof in Nickelodeon’s Rugrats.

My favorite TV reference comes in the “Pig Man” episode of Seinfeld, which ends with Kramer shutting a door on Jerry, George and Elaine:

TV ads have had a field day, including this 2009 Super Bowl commercial for Audi:

There has even been a popular video game series made from the film:

Legacy: Favorite vs. Greatest

I suppose such cultural impact should be expected from a movie that was the first to gross over $100 million, and at $133 million, was the highest grossing film of all time upon its release. Call it the Avatar (2009) of its day, only packing the kind of thematic directing techniques far outside Pandora’s horizon.

The Godfather thus represents the ultimate balance between commerical profibility and artistic expression. As New York Times critic Vincent Camby wrote, “Coppola has made one of the most brutal and moving chronicles of American life ever designed within the limits of popular entertainment.” (G) Within the limits of popular entertainment. While appealing to the masses often hamstrings artistic expression, Coppola proved that occasionally, just occasionally, a film will catch on in the mainstream that doesn’t sacrifice what it wants to say.

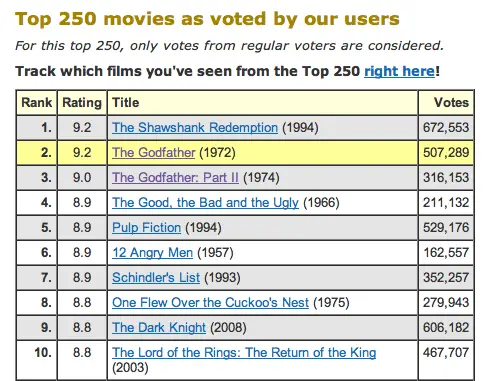

In total, the series garnered 29 Oscar nominations, including three for Best Picture, 9 Oscar wins, including two for Best Picture, and rave reviews, including a 100% on Rottentomatoes and Metacritic.com. It’s the godfather of best lists, where no films have ever had this much dominance. Even the inferior (and underrated) Part III hasn’t kept the series from ranking #2 on the AFI Top 100, #3 on Sight & Sound, #1 on Rolling Stone, #1 on Entertainment Weekly and #1 on TV Guide, to name a few. The debate over which is better, Part I or Part II, is a chicken-and-egg game that will keep movie buffs busy for centuries, for as Pauline Kael writes, the second film “enlarges the scope and deepens the meaning of the first film.” (G)

The series does just as well on fan polls. The Godfather is tied with The Shawshank Redemption for the highest score on IMDB.com (9.2), while The Godfather Part II comes in third (9.0). That’s two of the public’s three favorite movies.

Such dominance across both critic and public rankings makes The Godfather the most crucial of any movie in bridging the gap between the academic and the mainstream. Its own acclaim drives people to want to know why it’s the best, and its mainstream appeal almost insists upon it. If it’s not your favorite movie, many of you still admit that it’s the greatest, including M. Night Shyamalan:

Shyamalan’s distinction between cinematic art and “what makes you smile” is the essence of The Film Spectrum. Once you develop an understanding for the art side of the spectrum, the appreciation of art itself will become “what makes you smile.” Take it from Mr. Spielberg, the very guy who created the Raiders movie that makes Shyamalan smile. He is the mainstream king, the hit-maker, the feel-good doctor. Yet it was he who said this of The Godfather.

“I was pulverized by the story and the effect the film had on me,” Spielberg said. “I also felt that I should quit; that there was no reason I should continue directing because I would never achieve that level of confidence or the ability to tell a story. In a way, it shattered my confidence.” (A)

The thing is so masterful, it’s like directors are staring into the sun, then turning their heads because they know they can never match it. These are not films merely to watch, but to study. What poetry that Coppola would start his own wine company, because his two movie masterworks only get sweeter with time. The more you see them, the more you realize exactly who is getting whacked and why. You realize just how well Part I intertwines with Part II. You realize more layers are at work than you ever dreamed. Most of all, you realize you don’t have the upper hand in this; Coppola does. And after watching the films dozens of times, I have come to one conclusion: The Godfather saga is so masterful that it’s beyond our full first-time comprehension. Human eyes weren’t made that perfect.![]()

Citations:

CITE A: Todd Leopold, CNN.com article, Accessed 2008.

CITE B: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

CITE C: The “Tony Kornheiser Show” on Washington Post Radio, WWWT, Feb. 19, 2008

CITE D: The AFI Lifetime Achievement Award: Al Pacino, commemorative book

CITE E: Shyamalan interview promoting AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies: 10th Anniversary Edition. Accessed May 2007 on AFI.com.

CITE F: IMDB Trivia

CITE G: Piazza and Kinn, The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History

CITE H: AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies: 10th Anniversary Edition, CBS program