Director: Victor Flemming, George Cukor, King Vidor

Writers: L. Frank Baum (novel), Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf (screenplay)

Producers: Mervyn LeRoy, Arthur Freed (MGM)

Photography: Harold Rosson

Music: Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg

Cast: Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Jack Haley, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke, Terry the Dog, Clara Blandick, Charley Grapewin

![]()

The Rundown

- Introduction

- Plot Summary

- History’s Greatest Remake?

- Screenplay: Yellow Brick Road Map

- The Best Friends Anybody Ever Had

- Judy Garland: A Star is Born

- Over the Rainbow

- Oz: The Musical

- A Film of a Different Color

- Creating the Wonderful World of Oz

- Four Directors: The Men Behind the Curtain

- The Great and Powerful Mervin LeRoy

- Children’s Movie / Adult Themes

- Pop Culture

- Legacy

Introduction

There may be no greater testament to The Wizard of Oz than the vast demographics it covers, from theater types who adore Broadway’s Wicked to stoners who watch the film in sync with Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. After nearly 75 years, the film has transformed itself from mild box office showing to must-see annual TV event to timeless pop culture legend. It’s hard to think that the movie started as just that — a movie.

It’s almost impossible to look objectively at a film that’s so burned into our collective conscious that every song seems our own, every word feels part of our vocabulary and every touch appears as if fate intended it to be there. The film has become so mythical that many fans can no longer separate fact from fiction. Didn’t a Munchkin hang himself on screen? Aren’t there hidden metaphors for government policies? Wasn’t there some on-screen accident? Some off-screen illness? Some of these myths have been busted; others embraced. But one thing is for certain — a film that spawns so many legends must indeed be a legend itself.

![]()

Plot Summary

The story originated with the beloved children’s book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) by L. Frank Baum, who came up with the title by looking at the two letters printed on the bottom drawer of his filing cabinet (O – Z). (B) It’s a story we all know well.

Restless teen Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) lives a dull life on a Kansas farm with her Auntie Em (Clara Blandick) and Uncle Henry (Charley Grapewin). For entertainment, she looks to dog Toto (Terry the Wire Terrier) and three farm hands, Hunk (Ray Bolger), Hickory (Jack Haley) and Zeke (Bert Lahr). Still, she feels underappreciated on the farm, and when a mean old neighbor, Elmira Gulch (Margaret Hamilton), threatens to take Toto to the pound, she decides it’s time to run away from home.

After a brief run-in with fortune-teller hack Professor Marvel (Frank Morgan), Dorothy decides to return home — just as a massive tornado strikes — “It’s a twister! It’s a twister!” Dorothy is knocked unconscious by a broken window, sparking her crazy dream that the house has been lifted inside the cyclone (with she and Toto inside) and dropped inside the magical Land of Oz. Destination: Munchkinland. Address: The head of the Wicked Witch of the East.

Naturally, the witch’s sister, the Wicked Witch of the West (Hamilton), is mighty pissed off. She confronts Dorothy — and her little dog, too — but Glinda the Good Witch of the North (Billie Burke) steps in to protect her. She gives Dorothy the magical Ruby Slippers off the feet of the Wicked Witch of the East. Seeing as the shoes won’t come off as long as their owner is alive, the Wicked Witch of the West vows murderous revenge on Dorothy.

Meanwhile, Dorothy asks how she can possibly get back to Kansas. Glinda — with the help of singing Munchkins — tells her she must head to Emerald City and seek out the Wonderful Wizard of Oz. To get there, she must follow the Yellow Brick Road, where she encounters three instant companions, who agree to tag along so they, too, can ask the Wizard for various necessities. The Scarecrow (Bolger) desires nothing more than a brain, the Tin Man (Haley) wants to know what it feels like to have a heart, and the Cowardly Lion (Lahr) desperately seeks some courage.

When they arrive at Emerald City, they find the Wizard of Oz (Morgan) to be an intimidating force — a giant talking head, surrounded by pyrotechnics. The powerful Oz agrees to grant their requests, but says they must first bring him the broomstick of the Wicked Witch of the West. The foursome takes up the seemingly impossible challenge, but when the Witch captures Dorothy, it’s up to her brainless, heartless and spineless friends to storm the castle and save the day. After the Witch is undone by a bucket of water and the Wizard is revealed to be a fraud, Dorothy wakes up from her dream to decide, “There’s no place like home.”

History’s Greatest Remake?

Okay, so you could have recited that entire plot summary by heart. We all could have. It’s hard to imagine anyone imagining Oz any other way, but there was a time they did. In fact, the 1939 version was preceeded by many incarnations, starting with a live stage musical that toured the country for over 290 performances from 1902-1919, making it the longest running show of the decade. (B)

As for the silver screen, the first attempt was The Wizard of Oz (1908), followed by three renditions from the Selig Polyscope Company — The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1910), Dorothy and the Scarecrow in Oz (1910) and The Land of Oz (1910). Three more followed by Baum’s own short-lived Oz Film Manufacturing Company — The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1914), The Magic Cloak of Oz (1914) and His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz (1914). (B) This was followed by Chadwich Pictures’ silent The Wizard of Oz (1925), the first full-length feature, starring Oliver Hardy as the Tin Woodsman; a Technicolor animated short by Ted Eshbaugh in 1933; and another animated short by Kenneth McLellan 1938. (B) Cracked.com featured the film in its “surprise remakes” countdown.

Still, when it comes to MGM’s 1939 classic, I can only dock so many points for Originality. After all, this was both the very first musical version and the first live-action feature talkie version. It was also the first to do so many other things, like going from sepia to color and launching the era of Arthur Freed MGM musicals.

Screenplay: Yellow Brick Road Map

Of all these versions, it’s the 1939 film, written by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf — with uncredited help by Arthur Freed, Herman Mankiewicz, Sid Silvers, and Ogden Nash — that the AFI named the #1 Fantasy of All Time and the #10 Greatest Film of All Time. Much of this has to do with its brilliantly executed script, voted by the Writers Guilds in the Top 25 Screenplays of All Time, ahead of gems like Double Indemnity (1944) and Groundhog Day (1993).

It may be one of the best examples of classic story structure. Is there a better Break into Act Two than a tornado dropping the heroine in a faraway land? What better “Fun and Games” than meeting Munchkins and a trio of friends down a Yellow Brick Road? And what better All is Lost moment than being trapped in a witch’s castle with the hourglass running out?

The script cleverly features the dual worlds of Oz and Kansas, allowing for dual characters and plenty of foreshadowing — Hunk’s “You’d think you didn’t have any brains at all,” Zeke’s “Have a little courage, that’s all” and Hickory’s “Some day they’re going to erect a statue of me in this town.” (B)

Such dialogue was an asset unavailable to the silent versions, and the writers didn’t disappoint. While most movies would kill to have even one quote nominated for the AFI’s 100 Movie Quotes, The Wizard of Oz had six, including, “Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!” “I’m melting! Melting! What a world! What a world,” and “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!“

Three made the final list. At #99: “I’ll get you, my pretty, and your little dog too!“ At #23: “There’s no place like home.” And all the way at #4: “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” The lattermost has been referenced too many times to count, from Swingers (1996) to Avatar (2009):

Still, critic Kim Newman has a different pick for the best line in the film: “Hearts will never be practical until they can be made unbreakable.” (D)

The Best Friends Anybody Ever Had

The above line of course belongs to the Tin Man, the role that caused the most problems for the production. The original choice was Buddy Ebsen (The Beverly Hillbillies), who had already shot a chunk of the film, including the Tin Man’s musical number, when he had an allergic reaction to his skin make-up, made from actual silver dust. He had to be replaced by Jack Haley, whose son later married Garland’s daughter, Liza Minnelli. Haley’s flirtatious eyes to an apple-holding Garland are steamy foreshadowing.

Ironically, it could have just as easily been Ray Bolger who became ill, because it was he who was originally cast as the Tin Man. Luckily, he changed his mind and opted to play the Scarecrow instead. Of the three friends, his Scarecrow may very well be the popular favorite, thanks to his clumsy stumbles down the Yellow Brick Road and Dorothy’s ultimate admission, “I think I’ll miss you most of all.”

As for the Cowardly Lion (and Zeke), MGM cast comic stage actor Bert Lahr. His performance is instantly immitable, lending that signature New York accent to lines like, “I’ll fight you with one hand tied behind my back! I’ll fight on you one foot! I’ll fight you with my eyes closed!” He’s the ultimate scaredy cat, best on display in his hallway sprint and dive through an Emerald City window.

As for the wholesome Glinda, you couldn’t find a better actress than Billie Burke. Burke was a giant in showbuisness, named after her internationally-known clown father Billy Burke and husband of Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. of “Ziegfeld Follies” fame. Her Broadway career was portrayed by Myrna Loy in the film The Great Ziegfeld (1936), where Morgan and Bolger co-starred, and she earned an Oscar nomination for Merrily We Live (1938). At age 54, her ageless beauty lent the necessary feel of magic.

Still, the greatest performance in the entire film is that of Margaret Hamilton, who turned the Wicked Witch of the West into the AFI’s #4 Villain of All Time, behind only Hannibal Lecter, Norman Bates and Darth Vader. I don’t know who’s scarier, Hamilton’s Witch or Miss Gulch, whose circular bike theme is the epitome of evil. Tragically, Hamilton was sidelined with severe burns for a month after the fire came too early in one take of her trapdoor exit from Munchkinland.

Nothing arouses the deep fear within us like the Wicked Witch of the West. My grandfather teased me forever about how I used to say, “Fast forward it!” every time she came on screen. The great irony is that Hamilton started out as a kindergarten teacher. Perhaps to kids, she represents the most terrifying of authority figures, which is exactly what she played to Garland in Babes in Arms (1939). For years, Hamilton had a hard time convincing kids she wasn’t mean in real life, including an appearance on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood to explain that she was only acting. (C)

While Hamilton, Burke, Lahr, Bolger and Haley all had solid careers in their day, they now belong completely to Oz. None of these five are featured in David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film (2003).

The exception is Frank Morgan, who delivered back-to-back gems as The Wizard and Mr. Matuschek in The Shop Around the Corner (1940). Morgan reportedly showed up on the MGM lot every day carrying a black briefcase with just the right amount of alcohol. Surely behind the curtain, Oz was a drinker. (L) The eternally cranky W.C. Fields was considered for the part, but watching Morgan on screen, we can’t help but feel the generous man he was off it, until a fatal heart attack took him just 10 years after Oz.

![]()

Still, all of these casting pieces are built with but one purpose: to surround Judy Garland, the most famous and infamous star to come from the film. Unlike the others, she was at once synonymous with The Wizard of Oz and had the ability to transcend it. The daughter of a pair of vaudevillian performers, Garland was dancing on stage as soon as she could walk, and at age 13, she made her big screen debut in the MGM short Every Sunday (1936).

MGM had found their female counterpart to Mickey Rooney’s all-American boy, and the two teens were paired multiple times: Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry (1937), Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), Babes in Arms (1939), Strike up the Band (1940), Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941), Babes on Broadway (1941) and Girl Crazy (1943). The Rooney roles primed her for the role of a lifetime. So when 20th Century Fox refused to loan out Shirley Temple to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, Garland’s opportunity had arrived. (B)

The Wizard of Oz made her a household name. As Dorothy, she is timeless — innocent eyes, brown hair pulled into curly pigtails and breasts taped down under that checkered blue dress to make her look younger. At the 1940 Oscars, she received a special award “for her outstanding performance as a screen juvenile during the past year,” an honor previously awarded to Temple. It was the only “win” Garland ever had on Oscar night.

“Judy Garland touched audiences with her vulnerability, with her humanity, unlike any other star in Hollywood,” film historian Tony Maietta said. “She reached out to people and wrapped them up in her arms.” (K)

After Oz, her career was carried by two people — Busby Berkeley, who choreographed her in Babes in Arms, Strike Up the Band, Babes on Broadway and For Me and My Gal (1942), and husband Vincente Minnelli, who directed her in Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), The Clock (1945), Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and The Pirate (1947). In 1946, Garland and Minnelli gave birth to Liza, who said she couldn’t watch Oz as a kid: “It frightened me. It was like my mother was a little girl and these monkeys flew away with her. I didn’t like it, it was spooky. Then I saw it years later and I was amazed by it.” (J)

Unfortunately for the idolizing Liza, Garland also became one of Hollywood’s original test cases in a child star leading a tragic adult life. She divorced Minnelli in 1951, and went on to have three more husbands, though she spent much of her time married to drugs, severe diets and mental breakdowns. It just about ruined her career, until a worthy comeback in A Star is Born (1954). Garland should have won the Oscar that year, but lost to Grace Kelly for The Country Girl (1954). Her only other nomination was for Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), which some consider one of her worst performances. In her twilight, Garland would make several memorable talk show appearances, telling Jack Parr hillarious lies about the production of Oz. Then, in 1969, exactly three decades after Dorothy, she would be dead at the young age of 45. Decades later, Garland was voted the AFI’s #8 Greatest Actress of All Time.

Over the Rainbow

Plug Garland’s name into IMDB and you’ll find listings for both “actress” and “soundtrack.” For while Garland was a most charming actress, her greatest contribution to movie history was lending that beautiful vibrato to the signature song first performed here in Oz: “Over the Rainbow.” Composed by Harold Arlen (music) and E.Y. Harburg (lyrics), the Oscar-winning song is the ultimate dreamer’s ballad, assuring each of us that “the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.”

“‘Over the Rainbow’ has become part of my life,” Garland wrote to Arlen. “It’s so symbolic of everybody’s dreams and wishes that I’m sure that’s why some people get tears in their eyes when they hear it. I’ve sung it thousands of times and it’s still the song that’s closest to my heart.”

The song was one of many standards featured on Garland’s 1961 record “Judy Garland at Carnegie Hall,” which garnered five Grammy Awards and remained at the top of Billboard charts for two months. (G) It will without question stand the test of time, having already spanned Chet Atkins and Les Paul’s 1976 duet, which I want played at my funeral; Israel Kamakawiwo’ole’s 2004 medley with Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World,” Katharine McPhee’s performance in the 2006 finale of American Idol and Beyonce’s rendition during the 2007 CBS special Movies Rock:

Not only was it voted the AFI’s #1 Movie Song of All Time — above “As Time Goes By,” “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Moon River” — it was voted #1 on the Recording Industry Association of America’s “Songs of the Century.” That means it beat every song ever made. Period. It’s the standard by which all other standards are judged. Insanely, it was almost cut from the film for being “too sophisticated” for the young Garland.

Oz: The Musical

While “Over the Rainbow” won the Oscar for Best Original Song, composer Herbert Stothart won for Best Original Score. Stothart nails the instrumental segments of the film, from the commanding title suite (below), to the chilling looping tune of Miss Gulch’s bicycle; from the angelic wonder as Dorothy first steps into Oz, to the alarming sound as she watches the fleeting sands of the Witch’s hour glass.

How fitting that the film’s only Oscars came in musical categories, for Oz has to be the most famous musical ever done. Wait, you say, The Wizard of Oz is a musical? It seems we know the songs so well that we often forget its genre. In fact, it was the first musical ever produced by Arthur Freed, who would do more than 30 from 1939-1960 in MGM’s Golden Age, including classics like Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

The numbers in Oz rival all of those, and “Over the Rainbow” is only the beginning. The opening Munchkinland sequence includes a medley of “Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are,” “The House Began to Pitch,” “As Mayor of the Munchkin City, “As Coroner, I Must Aver,” “Ding Dong The Witch Is Dead” (#82 AFI Movie Songs), “The Lullabye League,” “The Lollipop Guild” and “We Welcome You to Munchkinland.”

From there, it’s “Follow the Yellow Brick Road,” “You’re Off to See the Wizard,” “If I Only Had a Brain” (below), “If I Only Had a Heart,” “If I Only Had the Nerve,” “The Merry Old Land of Oz,” “If I Were the King of the Forest,” and the oft-immitated “Winkie March” (“Oh-ee-oh, oh-um”). Harburg and Arlen wrote them all, earning The Wizard of Oz a #3 spot on the AFI’s 25 Greatest Musicals of All Time, behind only Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and West Side Story (1961).

A Film of a Different Color

Like all the great musicals of MGM’s Golden Age, The Wizard of Oz was a triumph of glorious Technicolor. For many in the public, The Wizard of Oz is believed (inaccurately) to be the moment movies first transitioned from black-and-white to color. In reality, color had existed from the very beginning of cinema, initially hand-painted one frame at a time. Even in the years right before Oz, the industry saw the muted palette of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the vibrant colors of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and the lavish display of Gone With the Wind (1939).

Even if Oz wasn’t the starting point, it remains the most symbolic because of its breathtaking transition from Kansas to Oz, where Dorothy opens the door from a sepia world to a wonderful world of color. Imagine how magical it must have been for Depression-era audiences to start off watching a dreary, sepia Kansas, and then suddenly have Dorothy open the door to a world of color? Imagine all those folks decades later who watched annual broadcasts on black-and-white televisions, only to get their first color set and be knocked out by the change from sepia to color?

The transition back to sepia at the film’s conclusion only reminds us how much we’ve enjoyed the colors all along. Let’s face it. This film was made for color — ruby red slippers, Yellow Brick Roads, an Emerald City, and a “horse of a different color” (animal rights activists wouldn’t allow painting the horse, so the filmmakers applied a paste of water mixed with fruit-flavored jello powders). (F)

Creating the Wonderful World of Oz

While beautiful, the three-strip Technicolor film required massive lighting, creating temperatures that topped 100 degrees. This was all the more brutal because so many in the cast were cloaked in extravagant costumes. The hottest was no doubt Lahr, whose layered lion suit, perm mane and visible mask forced him to take frequent water breaks to avoid dehydration. (F)

The costumes were designed by Hollywood’s famous one-name designer, Adrian, who that same year also designed the garb for Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939) and Cukor’s The Women (1939). An Academy Award surely was surely deserved, but the category did not exist until 1948! Costumes like this were for the stage, not the movies. Adrian changed all that with a pointy-hatted witch, extravagant munchkins, a straw-stuffed scarecrow, funnel-capped tin man, talking trees and flying monkeys.

Oscar nominations did go to Cedric Gibbons and William A. Horning for Art Direction, and deservedly so. The Wizard of Oz features a number of magnificent sets, from Munchkinland to Emerald City, from the witch’s forest to her intimidating castle fortress.

Some may knock the sets for their clear “stagecraft,” but I believe this “phoniness” is completely intentional. The artificial sets allow for a stark contrast between the gritty, spaces of Kansas and the wondrous, dream world of Oz.

“It starts out as a semi-realistic film … [but] when it goes to Oz, it’s like a stage musical,” says director Harold Ramis (Animal House). “The floors are polished everywhere in Munchkinland. You’re clearly on stages, there’s no question. The sets and props, everything looks like it’s cardboard. It’s very flat and two-dimensional, the trees look phony. But it really doesn’t matter at all. … You just go with it.”

Another Oscar nomination came for special effects, a nomination shared by A. Arnold “Buddy” Gillespie (effects photography) and Douglas Shearer (sound effects). For Gillespie, the man who made MGM’s “Leo the Lion” roar, it was his first of 12 nominations for special effects, including three wins for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), Green Dolphin Street (1947) and Ben-Hur (1959). In 1964, the Academy awarded him a special Technical Achievement Award for “engineering an improved Background Process Projection System.” Still, The Wizard of Oz remains his greatest achievement. (H) When you have a chance to see the film again, stop and marvel at the amazing quality of effects being executed for 1939.

Most impressive is the tornado ripping through Kansas, achieved by a funnel made of muslin, the top attached to a gantry that moved the full length of the stage, and the bottom attached to an “s”-path in the floor. This leads into yet another effect as the farm house is lifted up into the cyclone. This was achieved by dropping a miniature house away from the camera, shooting it in slow motion, then playing it backwards, so that it looked like it was falling toward the camera.

Other examples include Glinda floating in on a pink bubble; the Witch coming and going in a great ball of fire; the legs of the Witch of the East shriveling away under the house; a superimposed Glinda making it snow amongst deadly poppies; and the Wizard’s holographic talking head amidst fireballs and smoke.

There’s also the flying monkeys taking flight; the Witch’s aerial smoke message aboard a broomstick; the Tin Man lifting straight out of the screen; the Scarecrow being ripped to pieces in the Witch’s forest; the magic of the Witch’s crystal ball; the melting witch (via trapdoor); and the “ring” effect of Dorothy clicking her heels back to Kansas.

Four Directors: The Men Behind the Curtain

“People come and go so quickly here.” Effects guru Gillespie was one of the few constants throughout the production, as The Wizard of Oz went through a total of four directors. For almost two weeks, the project was helmed by Richard Thorpe, whom producer Mervyn LeRoy canned because he didn’t capture the proper “childlike quality.” In the interim, director George Cukor stepped in, as he had a few days open before he started work on Gone With the Wind (1939). It was Cukor who told Garland to take off half her makeup and to lose her blonde wig in favor of her natural brunette. (H) When Cukor left for Gone With the Wind, LeRoy made a surprise turn to the macho Victor Fleming, who directed most of the picture.

“Of course, some people do go both ways.” With just weeks left of shooting, Fleming got an emergency call from producer David O. Selznick asking him to take over Gone With the Wind, due to a fallout between he, Cukor and Clark Gable. Fleming agreed, handing the Oz reigns over to King Vidor, who had directed such silent classics as The Big Parade (1925) and The Crowd (1928). (H)

“They had just taken George Cukor off Gone With the Wind, and Selznick gave me this stack of scripts to take home over the weekend,” said Vidor. “I spent from about Friday afternoon to Monday morning reading and studying and worrying about them. … Monday morning I got up and I thought, ‘God, I don’t want to take this on.’ I wanted about three months or six months to adapt [Gone With the Wind] and get used to it, at least a month or so, so I went in saying I didn’t think I wanted to do it. In the meantime, Clark Gable had worked with Victor Fleming, who … said he would do Gone With the Wind if someone would take The Wizard of Oz. I was so damn glad to get out of doing Gone With the Wind that I said, ‘Sure, I’ll take over The Wizard of Oz.'” (I)

In ten days, Vidor shot all of the sepia Kansas sequences, including “Over the Rainbow,” but refused to take a director’s credit. “Fleming had been in there on all the casting and designing sets and locations and all this sort of stuff, so I thought for somebody to come in for two weeks when most of the sets were up and the picture was all cast, he shouldn’t get credit, and neither did the Directors Guild,” Vidor said. “My name isn’t on The Wizard of Oz — I wouldn’t permit it.” (I)

And just like that, Fleming received sole director’s credit on both The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind in the same year. Together, they remain the greatest one-two punch by a single director in the same year in the history of movies. It’s hard to imagine it ever being topped, if only because so much work goes into just one project. Of course, Fleming was no auteur genius. Call him solid, reliable, capable, but “master” does not quite fit. Even so, he was nominated for the Golden Palm at Cannes and the film ranked #41 on Sight & Sound‘s Directors Poll with 5 votes.

The Great and Powerful Mervyn LeRoy

Aside from sharing Cukor and Fleming, The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind also stand as triumphs of hands-on producers. Just as Selznick commanded Gone With the Wind, it was Mervyn LeRoy who gave The Wizard of Oz its consistent vision throughout the upheaval of four directors. A famous director in his own right — Little Caesar (1930), I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) — LeRoy was handpicked by MGM head Louis B. Mayer to head up the project from the start. It was LeRoy who cast Judy Garland. And it was LeRoy who had to facilitate one of history’s grandest production spectacles.

In addition to the sets, costumes, make-up, effects and Technicolor lighting, LeRoy had to organize a cast of literally hundreds of little people. Billed as “The Singer Midgets,” the Munchkins were mostly vaudeville and circus freelancers, most famously the green-wearing Jerry Maren, whom Fleming liked so much he placed him in multiple shots, continuity break or no continuity break. Undoubtedly, the Munchkins are one of the film’s most famous elements, and their voices were made to sound even more high-pitched in post-production for an even jollier romp through Munchkinland.

Which brings us to the question of the munchkin committing suicide. It’s all a fabrication. If you look closely, you’ll see that it’s the flap of a bird’s wing, not the hanging of a body.

Children’s Movie / Adult Themes

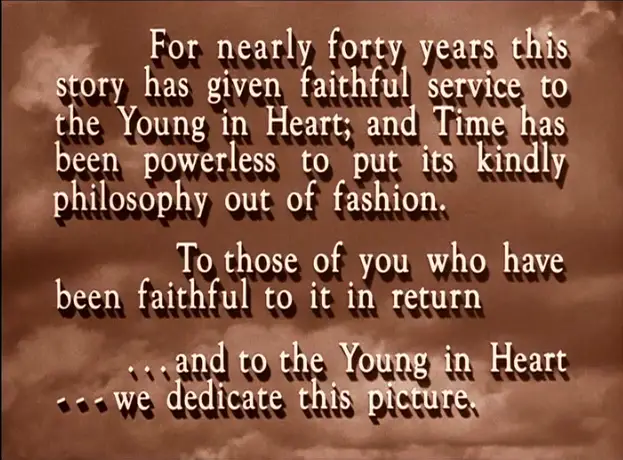

Throughout the process, LeRoy heard complaints that the film was for children and no one would want to see it. His response? “I want to see it. I’ve wanted to see it since I was a kid.” (I) Fleming agreed: “I made the film because I wanted my two little girls to see a picture that searched for beauty and decency and sweetness and love in the world.” (H) You can see LeRoy and Fleming’s mission in the prologue, dedicating the film to the “Young in Heart.”

While the film may be geared toward youth, adults should reconsider The Wizard of Oz for its layers upon layers of deeper meanings. Parents can sit back and enjoy The Wizard of Oz anew, realizing a depth of theme they never knew existed as kids.

“I think it is so much about God and faith, and good and evil, and what you need to go through in order to grow and in order to come home to yourself,” said Jennifer Grey (Dirty Dancing). “My daughter Stella is three years old, and she discovered The Wizard of Oz about a month ago, and she is in full-on obsession with Dorothy, all day every day. I’m enjoying it so much more again now.” (E)

In 1967, Henry M. Littlefield theorized in American Quarterly that the entire story is an allegory for U.S. populism and monetary policy in the Gilded Age, namely the 1896 presidential election between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan. Indeed, this was Topic #1 around the time Baum wrote his book.

Littlefield claims every element is symbolic — The Scarecrow (naive farmers of the west); the Tin Man (dehumanized factory workers of the east); the Wicked Witch of the East (Eastern industrialists and bankers who control the people); the Good Witch of the North (populist New England); the Good Witch of the South (the populist South); Dorothy (a young Mary Lease, or simply the good-natured American people); Dorothy’s shoes (silver in the book, as the Populists wanted “the free and unlimited coinage of silver”); the Yellow Brick Road (the gold standard, paved with gold, but leading nowhere); the Land of Oz (“oz” abbreviating “ounce,” i.e. silver and gold); Emerald City (Washington D.C. with its U.S. Treasury greenbacks); the Wizard (President Grover Cleveland or Republican Presidential candidate William McKinley); and the Cowardly Lion (Democratic-Populist candidate William Jennings Bryan, famous for his “cross of gold” speech). (B)

Such a reading adds new weight to “the man behind the curtain,” calling the Republican William McKinley a phony, and “cowardly lion,” saying Democrat William Jennings Bryan doesn’t have what it takes to sell his populist message. Some even find warnings against religion in Professor Marvel’s “psychic” abilities, a commentary on drug culture in “poppies will put them to sleep,” and a warning against runaway technology in the Wizard’s uncontrollable weather balloon.

Pop Culture

The “munchkin hanging” and “cross of gold” political commentary are just two of the countless legends in a film that may be the most referenced film of all time. The pop culture references began almost immediately, with Jimmy Stewart singing a drunken “Over the Rainbow” to Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story (1940). They continued with “The Oz Kids” animated series in the ’60s, and by the early ’70s, Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory (1971) was echoing the film with its own little people (Oompa Loompas) and its own door opening to a candy-colored reveal (the Chocolate Room).

As the ’70s continued, Oz references began to become more bizarre, from the lost Oz “Jitterbug” dance showing up in That’s Entertainment! (1974), to the film syncing up perfectly with Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). Here are a few of the clever connections between the album and the movie:

The same year as Pink Floyd’s album, Elton John released his 1973 album “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” which went all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard charts.

In the late ’70s, George Lucas payed homage with Obi Wan’s “melting” death in Star Wars (1977); Sidney Lumet directed Diana Ross and Michael Jackson in the African American spin-off The Wiz (1978) (see below); and Jim Henson copied entire plot elements in The Muppet Movie (1979), including Kermit’s voyage to Hollywood (Oz). (B)

The ’80s brought the pop band Toto; the Chevy Chase/Carrie Fischer movie Under the Rainbow (1981); the Japanese animated version, Ozu no Mahotsukai (1982); E.T. trying to phone his own “no place like home” (1982); Ralphie encountering an Oz-obsessed kid in A Christmas Story (1983); Disney’s live-action sequel Return to Oz (1985); references by TV’s Ninja Turtles (1987); and Robin Williams chanting, “Follow the Ho Chi Minh Trail” in Good Morning Vietnam (1987).

Robert Zemckis spoofed “I’m melting” during Judge Doom’s death in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). The same line was spoofed by the ghosts disappearing into corn in Field of Dreams (1989).

The ’90s brought multiple references in David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990); a Saturday morning cartoon The Wizard of Oz (1990); a tornado-tracking device named “Dorothy” in the blockbuster Twister (1996) (see below); an “Over the Rainbow” radio signal and the words “THIS WAY TO OZ” on a hot air balloon in Contact (1997); the playing of “Over the Rainbow” in the bloody finale of Face/Off (1997); the hit HBO prison series Oz (1997); and a “not in Kansas” line to Neo in The Matrix (1999).

The new millennium brought Oprah regular Dr. Oz.; Harry Potter (2001) flying on broomsticks; rapper Techn9ne spoofing the “Winkie March” in his song “Einstein;” Eminem’s autobiographical song “Yellow Brick Road;” and Stephen Schwartz’s 2002 Broadway smash Wicked, based off Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West.

In case you missed it in the “screenplay” category, here’s a second look at the countless times Dorothy’s “we’re not in Kansas” line has been referenced, from Swingers (1996) to Avatar (2009):

Legacy

For all this popularity, The Wizard of Oz was far from a box office success. Despite enthusiastic reviews and a powerful premiere, it grossed just $3 million and didn’t turn a profit until its 1949 re-release. (B) This was in part because the film had been MGM’s most expensive film to date. (H) Oz was completely overshadowed by Gone With the Wind, the highest grossing movie of all time (adjusted for inflation) and winner of eight Oscars, including Best Picture. Still, over the long hull, I’d venture to say more people have seen The Wizard of Oz than Gone With the Wind, thanks to its shorter runtime and appeal to kids. Dare I say it’s the most watched movie in the history of the world?

Television first brought it into our households on November 3, 1956, airing on CBS the Sunday before Thanksgiving with an introduction by Bert Lahr and Liza Minnelli. It aired again in December, 1959, at which point it became a yearly event. With so few channels to choose from, families anxiously waited each year to see the annual prime-time broadcast. (A) This helps explain why TV Guide voted it the #4 Greatest Film of All Time. Unfortunately, that luster has faded since the advent of: (a) cable, allowing stations to air the film multiple times a year; (b) VHS, allowing parents to tape it for their kids; and (c) DVD, allowing fans to watch it whenever they want.

Even so, its association with “family time” endures. It’s a safe bet that all of our grandmothers have a sign or decorative pillow somewhere in the house that reads, “There’s no place like home.” This is how much the film is a part of us, how much it has infiltrated our households, from books to board games to dolls.

It is adored by families because it affirms their importance. As Dorothy says at the end of the film, “If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own back yard.” Critic Kim Newman called the ending a “cop-out,” arguing that Garland would never prefer the dreary Kansas over the wonders of Oz. While this may be true, it makes you wonder — why is it that The Wizard of Oz and It’s a Wonderful Life are two of the most beloved movies in American history? Can it be that deep down we all desire what’s closest to us, yet can’t realize it until we’ve gone away? Is it the classic “you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone,” or is Dorothy’s homecoming less literal, saying we all must “come home to ourselves” and make peace with our past?

Like the film’s message, its own legacy is grounded in our roots. After all these years, the ruby slippers remain one of the biggest attractions at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, so much that the museum had to replace the carpet in front of the display case. (A) If what the Wizard says is true, that “a heart is not judged by how much you love, but by how much you are loved by others,” The Wizard of Oz has the biggest heart of any film ever made.

![]()

Citations

CITE A: The Legacy of Oz, DVD Special Feature

CITE B: Tim Dirks, filmsite.org

CITE C: Margaret Hamilton’s IMDB Bio

CITE D: Kim Newman, 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

CITE E: AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes

CITE F: Glorious Technicolor, Turner Classic Movies documentary

CITE G: Judy Garland’s IMDB Bio

CITE H: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic (DVD Special Features)

CITE I: George Stevens J.r, The Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age

CITE J: Splash News via MetroLyrics.com. URL: http://www.metrolyrics.com/2010-liza-minnelli-the-wizard-of-oz-was-frightening-news.html

CITE K: Turner Classic Movies documentary, Moguls and Movie Stars: A History of Hollywood — “Brother Can You Spare a Dream?”

CITE L: David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film