Director: Spike Lee

Producer: Spike Lee (40 Acres & a Mule)

Writer: Spike Lee (screenplay)

Photography: Ernest R. Dickerson

Music: Bill Lee, Public Enemy

Cast: Spike Lee, Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Samuel L. Jackson, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, John Turturro, Martin Lawrence, Frank Vincent, Bill Nunn, John Savage, Paul Benjamin, Frankie Faison, Robin Harris, Joie Lee, Miguel Sandoval, Rick Aiello

![]()

Introduction

Is it a coincidence that Barack Obama took Michelle to see Do the Right Thing on their first movie date? Is it fate that exactly 20 years later, America swore in its first black president? Or does the moral arc of the universe not only bend toward justice, as Dr. King said, but also to cinematic influence?

No doubt, the entertainment industry led this shift from 1989 to 2009, with comedians from Bill Cosby to Dave Chappelle, actors from Will Smith to Denzel Washington, talk show hosts from Oprah Winfrey to Whoopi Goldberg, athletes from Jerry Rice to Michael Jordan, and musicians from Michael Jackson to Tupac Shakur. By the new millennium, the paradigm had shifted such that youngsters only knew a world where the best rapper was white (Eminem) and the best golfer was black (Tiger Woods). You want to achieve racial harmony? Mesh the “8 Mile” beatbox with the “8th Hole” tee box.

But this revolutionary period did not come without the divisive turmoil of Rodney King, the L.A. Riots, the O.J. Simpson trial, Hurricane Katrina, Reverend Jeremiah Wright and, on New Year’s Eve 2008, halfway between President Obama’s election and his inauguration, the shooting of Oscar Grant, which later became the Sundance winner Fruitvale Station (2013), released the same week as the Trayvon Martin verdict. As the dust settles from each, we’re reminded of how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go. Surely just because we’ve elected — and re-elected — a black president doesn’t mean racial inequality is over. Simply look at statistics of poverty, education and incarceration. But through each blood burning moon, we should all continue to find hope in the extraordinary progress made thus far.

This entire journey would not have been possible without Do the Right Thing, the seminal game changer in cinema’s handling race, timed perfectly with the zeitgeist of Public Enemy’s opening cry, “1989!” It was a long time coming, from the racism of The Birth of a Nation (1915) and The Jazz Singer (1927); the mixed bag of Gone With the Wind (1939); the early salvos of The Searchers (1956), Giant (1956) and The Defiant Ones (1958); the Civil Rights stalwarts of To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and In the Heat of the Night (1967); the blaxploitation of Shaft (1971) , Superfly (1972) and Foxy Brown (1974); period pieces like Roots (1977) and The Color Purple (1985); and finally the ’89 trifecta of Do the Right Thing (1989), Glory (1989) and Driving Miss Daisy (1989).

While Daisy and Glory got all the Oscar love that year, they both had the safety net of hindsight, looking back judgmentally at the sins of the past. That’s much easier than holding a bright light on the sins of the present. Spike Lee had the guts to make a social commentary in the fierce present of the now. His daring film dared us to choose sides in our initial reactions — rolling the credits with two opposing quotes by Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcom X — then allowing us to admire his painstakingly fair treatment of all sides over repeat viewings. When Crash (2004) ultimately won Best Picture, it was a make-up Oscar for the film that should have won it 15 years earlier, a film that was truly ahead of its time, a film that still burns with the resonance of the glaring choice in its title: Do the Right Thing.

![]()

Plot Summary

The film takes us into the predominantly black neighborhood of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, where the temperature on the hottest day of the summer becomes a symbol of the racial tension about to boil over. Our guide is Mookie (Spike Lee), a pizza delivery boy who’s so broke that he lives with his sister Jade (Joie Lee). He also has a son with his girlfriend Tina (Rosie Perez), who chides him for not coming around more often. Mookie cares for his girlfriend and his son, but most of his time is taken up at Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, run by Sal (Danny Aiello), who proudly displays famous Italian Americans on his wall, and his two sons, the racist Pino (John Turturro) and the open-minded Vito (Richard Edson).

A number of unique characters come in and out of the restaurant: Da Mayor (Ossie Davis), a wandering drunk with a voice of reason; Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), who boycotts the restaurant for not having any black faces on the wall; Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), a mammoth of a man who walks around blaring “Fight the Power” on his boombox; and Smiley (Roger Guneveur Smith), a stuttering local who sells photos to spread awareness about Malcom X and Martin Luther King Jr. Standing watch over the entire block is the neighborhood conscience, Mother Sister (Ruby Dee), and the ever-present disc jockey, Mister Senor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson) of We Love Radio 180 FM.

As events transpire throughout the day, the racial tension ratchets up, until Radio Raheem refuses to shut off his boombox in the pizzeria and Sal smashes it with a baseball bat. All hell breaks loose in a brawl between the Italians and the neighborhood blacks, where it’s hard to tell who’s wrong and who’s right. But when the police roll up, and Sal stands idly as a cop chokes Radio Raheem to death, it’s clear to Mookie that a place of business is no comparison to a person’s life. He walks across the street, grabs a trash can and sends it flying through the restaurant window — the smash heard round the world.

![]()

Ensemble Cast

To pull off such a complex ensemble piece, Lee surrounded himself with one of the deepest casts in recent memory. Danny Aiello follows strong roles in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) and Moonstruck (1987) with another stellar antagonist. Aiello earned the film’s sole Oscar nomination, which said as much about his strong performance as it did the prejudice of Oscar voters at the time. A number of the film’s black actors and actresses would have been just as worthy of a nomination, including Giancarlo Esposito, who plays the outspoken opposite of his silent meth dealer Gus in AMC’s Breaking Bad.

The famous husband and wife team of Ruby Dee (A Raisin in the Sun) and Ossie Davis both won NAACP Image Awards. Davis benefits from a character that’s more clearly drawn than Dee’s, but both serve as the elder conscience of the neighborhood.

While Dee and Davis were examples of veteran actors getting a chance to once again shine, the film also allowed up-and-coming superstars to rise, the biggest of which was Samuel L. Jackson. He was the perfect cast to deliver the cool lines of a DJ, appearing just a year after Coming to America (1988), a year before getting whacked in GoodFellas (1990) and five years before his career role in Pulp Fiction (1994). In a way, Jackson and Lee came up together, through School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Mo’ Better Blues (1990) and Jungle Fever (1991), where he stole the show as the junkie brother.

Perhaps the next biggest star to come from the film was a debuting Martin Lawrence, who three years later got his own self-titled TV ashow, Martin (1992). That’s right, without Do the Right Thing we may never have said “Damn, Gina” or laughed to Bad Boys (1995), Blue Streak (1999) and Big Momma’s House (2000).

The film also features the familiar faces of John Turturro, a year before joining the Coens for Miller’s Crossing (1990) and Barton Fink (1991); Richard Edson, who had played one of the bored New Yorkers in Stranger Than Paradise (1984); John Savage, who was handicapped in The Deer Hunter (1978); and Frank Vincent, whose Billy Batts was slaughtered in a trunk the following year in Goodfellas (1990).

![]()

Equal Opportunity Racism

Believe it or not, assembling the deep cast was the easy part. Spike Lee’s most difficult challenge was deciding how exactly he would attack the problem of racism in America. Should he make it an indictment solely of white-on-black racism? Or, should he make it a movie with equal opportunity racism, where members of all races share in the responsibility?

Thankfully, Lee chooses the latter, thus establishing an unbiased credibility that’s necessary to win over hearts and minds. Note how Jade appreciates Buggin’ Out’s passion, but criticizes his vitriolic approach:

BUGGIN’ OUT: We don’t want nobody in there, nobody spending good money in Sal’s until we get some black motherfuckin’ pictures on the wall.

JADE: Buggin’ Out, what good is that gonna do? Huh? You know, if you really tried hard, Buggin’ Out, you could direct your energies in a more useful way, you know?

BUGGIN’ OUT: Jade, you got to be down. What, you ain’t down? Are you down for that?

JADE: Yeah, Buggin’ Out, I’m down. But I’m down for something positive in the community.

As a filmmaker, Spike Lee takes Jade’s advice to heart, directing his energies in a balanced, constructive way. Throughout the film, he is extra careful to avoid an “us vs. them” construction. It would have been near impossible for white audiences to buy into his message if he unrealistically stacked his deck against non-blacks. Instead, Lee suggests there’s plenty of blame to go around.

Note how the three street-corner black folks express their hatred for the neighborhood Koreans, saying it’s a shame that a Korean business is succeeding in a black neighborhood. One of them, Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris), calls a Korean man “kung fu” to his face. Even the film’s sympathetic martyr, Radio Raheem, is not immune to his own prejudices. Watch how he mocks the Korean store owners while trying to buy batteries. Fittingly, this comes at a moment when his freedom music has died.

Note also how a group of young black teens ridicules a white man (John Savage) for living in their neighborhood. The scene is set up as a classic white vs. black clash, divided among fans of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird. Ironically, Lee depicts the white man as the sympathetic one. When the black group angrily tells him to move back to Massachusetts, he emphatically states, “I was born in Brooklyn,” as Lee’s camera symbolically looks down upon the prejudiced black men.

These are just several attempts by Lee to call the racial game honest. For each scene that champions black figures (“Dwight Gooden is the best in the game!”), there is another attempt to play it straight (“Mike Tyson ain’t shit. I remember when he mugged that woman right there on Lexington”). Only because Lee has established a credibility here can he proceed to score major victories against white-on-black racism.

The most powerful scene in this regard comes when Mookie hears Pino slur under his breath (“Fuckin’ n*ggers are so stupid”), then pulls him aside for a serious chat. By simply appealing to reason, Mookie paints Pino as tongue tied, hypocritical and ignorant:

MOOKIE: Pino who’s your favorite basketball player?

PINO: Magic Johnson.

MOOKIE: Who’s your favorite movie star?

PINO: Eddie Murphy.

MOOKIE: Who’s your favorite rock star? Prince. You’re a prince fan…

PINO: Nah, the Boss. Bruce!

MOOKIE: Prince.

PINO: Bruuuuce!

MOOKIE: Pino, all you talk about is nigger this and nigger that, and all your favorite people are so-called niggers.

PINO: It’s different. Magic, Eddie, Prince, they’re not niggers. I mean, they’re not black. I mean, let me explain myself. They’re not really black. I mean, they’re black, but they’re not really black. They’re more than black. It’s different.

MOOKIE: It’s different?

PINO: Yeah, to me it’s different.

MOOKIE: You know deep down inside, I think you wish you were black.

PINO: Get the fuck out of here!

MOOKIE: Laugh if you want to. You know your hair is kinkier than mine. What does that mean? And you know what they say about dark Italians…

PINO: You know, I’ve been listenin’ and readin’.

MOOKIE: You’ve been readin’ now?

PINO: I read. I’ve been readin’ about your leaders, Reverend Al “Mr. Do” Sharpton, Jesse “Keep Hope Alive!”

MOOKIE: That’s fucked up.

PINO: “Keep Hope Alive!”

MOOKIE: Hey, that’s fucked up. Don’t talk about Jesse.

PINO: And even, the other guy, what’s his name? Fara-man, Fara-kan.

MOOKIE: Minister Farrakhan.

PINO: Minister Farrakhan. Anyway, Minister Farrakhan always talks about the so-called day when the black man will rise. We will one day, what does he say, we will one day rule the earth as we did in our glorious past?

MOOKIE: That’s right.

PINO: What past you talkin’ about? What did I miss???

MOOKIE: We started civilization.

PINO: Keep dreamin’ man. Then you woke up!

MOOKIE: Pino, fuck you. Fuck your fuckin’ pizza. And fuck Frank Sinatra.

PINO: Yeah? Well fuck you, too. And fuck Michael Jackson.

Then, just after Mookie’s calm debate with Pino, Lee inserts a montage of multiple characters, all of different races, staring directly into the camera and hurling racial stereotypes used all too often in our society:

BLACK MOOKIE: You dago, wop, garlic-breath, guinea, pizza-slinging, spaghetti-bending, Vic Damone, Perry Como, Luciano Pavarotti, Sole Mio, nonsinging motherfucker!

ITALIAN PINO: You gold-teeth, gold-chain-wearin’, fried-chicken-and-biscuit-eatin’, monkey, ape, baboon, big thigh, fast-runnin’, high jumpin’, spear chuckin’, three-hundred-sixty-degree-basketball-dunkin’, titsun spade Moulan Yan. Take your fuckin’ piece of pizza and go the fuck back to Africa.

PUERTO RICAN STEVIE: You little slanty-eyed, me-no-speak-e-American, own every fruit and vegetable stand in New York, bullshit Reverend Sun Yung Moon, Summer Olympic ’88, Korean kick-boxing son of a bitch!

WHITE OFFICER LONG: Goya bean-eating, fifteen in a car, thirty in an apartment, pointy shoes, red-wearing, Menudo, meda-meda Puerto Rican cocksucker. Yeah, you!

KOREAN CLERK: It’s cheap, I got a good price for you, Mayor Koch, “How I’m doing?” Chocolate-egg-cream-drinking, bagel and lox, B’nai B’rith, Jew asshole!??

LOVE DADDY: Yo! Hold up! Time out! Time out! Y’all take a chill. Ya need to cool that shit out! And that’s the double truth, Ruth!

![]()

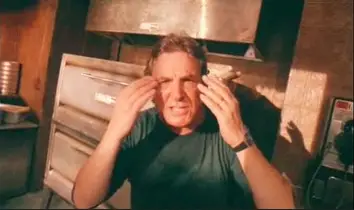

Spike Lee: Both Sides of the Camera

While such sequences are hard to watch, they prove Lee’s genius. He understands full well that candy-coating racism isn’t going to solve anything. We need to see it for all its ugliness and all its ignorance, the way it really is out there in the real world. By having his characters stare at us in direct camera address, breaking the so-called “fourth wall,” it forces us into the shoes of various races, to literally “climb inside others’ skin and walk around it,” as Atticus Finch memorably said in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

With each direct camera address, Spike Lee stared into our soul and challenged us to change. For this, he is a pivotal American figure, not only as an on-screen presence wearing a Jackie Robinson jersey, red shorts, gold teeth and parted fade hairdo, but as the most important black director of the 20th century, opening the door for John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991), Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day (2001), Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013) and Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave (2013).

He remains one of NYU’s most famous graduates, winning a student Academy Award for his 45-minute flick Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (1983) and following with his feature breakthroughs She’s Gotta Have It (1986), a modern sex comedy, and School Daze, a mockery of fraternities. While he continued to make good films after 1989, from Jungle Fever (1991) to Malcom X (1992) to Inside Man (2006), Do the Right Thing remains the most important “Spike Lee Joint” and the only film to earn him an Academy Award nomination for a fiction film.

Spike’s sizzling script was nominated for Best Original Screenplay on its way to being voted the WGA’s #93 Greatest Screenplay of All Time, just one spot behind Psycho (1960). The script is simultaneously a masterpiece of comedy (“We have a Jheri curl alert. If you have a Jheri curl, stay in the house or you’ll end up with a permanent plastic helmet on your head”); a celebration of black cultural history (Jackson’s DJ listing the great African American musicians from Steve Wonder to Ella Fitzgerald); and dialogue with double meaning. The opening words serve not only a plot function — “Wake up! Uppy wake!” — but also a thematic call to action, telling viewers to wake up to the racial injustices around them. Jackson goes on to say another line with obvious double meaning, “The color for the day is black, that’s right black, so you can absorb some of these rays and save some of that heat for winter.”

Lee also shows his mastery of movie history in the scene where Mookie bumps into Radio Raheem on the street. Raheem looks directly into the camera to tell “the story of right hand, left hand,” an obvious homage to Robert Mitchum in The Night of the Hunter (1955), only instead of tattoos on Mitchum’s knuckles, Raheem wears a pair of brass knuckles that spell LOVE on the right hand and HATE on the left for an unforgetable play-by-play of a symbolic boxing match:

RADIO RAHEEM: Let me tell you the story of right hand, left hand. It’s a tale of good and evil. HATE — it was with this hand that Cain iced his brother. LOVE — these five fingers, they go straight to the soul of man, the right hand, the hand of love. The story of life is this: static. One hand is always fighting the other hand, and the left hand is kicking much ass. I mean, it looks like the right hand, LOVE, is finished. But hold on, stop the presses, the right hand’s comin’ back! Yeah, he’s got the left hand on the ropes now! That’s right! Yeah! Oooh! It’s a devastating right and HATE is hurt! He’s down! Oooh! Oooh! Left hand hate KO’d by love!

This brass knuckle reinterpretation, combined with the direct address of racial epithets, would alone make Do the Right Thing a classic flick. But they’re just two isolated moments in an overall work of directorial brilliance. Throughout the film, Lee creates a colorful urban backdrop shown in off-kilter dutch angles, reminding us that everything is unstable and the entire balance could tip at any second.

Lee’s dynamic style is most evident in the sequence set to the song “You Can’t Stand the Heat,” where we get an underwater shot of Tina dipping her face into a tub of ice cold water, followed by a shot of Jade in the shower, the water dripping over her face in slow motion.

Note also how the light from the window flickers with the spinning of a ceiling fan during the sex scene.

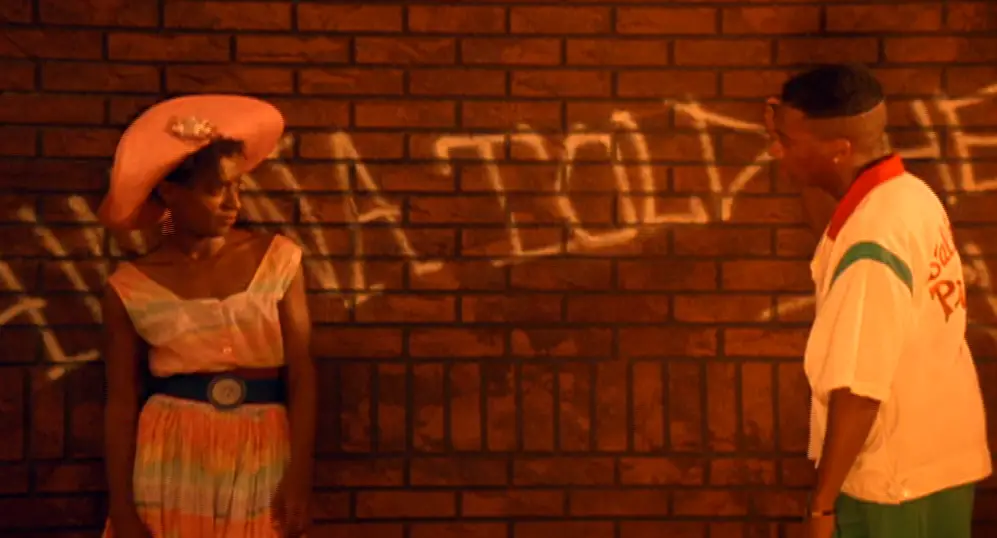

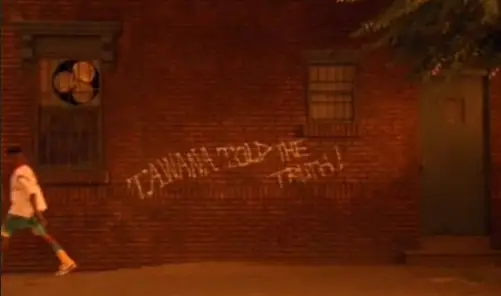

Lee also makes effective use of mise-en-scene (symbolic placement of all elements in the frame). He begins with slow-motion pans across Mookie and Pino’s disgusted faces as Sal flirts with Jade, then follows Mookie outside as he warns Jade that all Sal wants to do is play “hide the sausage.” Mookie’s warnings against Sal’s advancements are symbolicaly shot against a brick wall with the graffiti “Tawana told the truth,” a blatant statement about the 1988 interracial rape case involving Tawana Brawley.

Ironically, the film does not include the technique most associated with Lee: the double dolly shot. Perhaps he needed to unleash some “double truth, Ruth” before he could unleash the double dolly, Miss Molly.

In the end, Lee was nominated for the top prize in the global film community, the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. While he lost to Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape (1989), which did for sex what Lee did for race, Lee won Best Director by both the Chicago Film Critics Association and Los Angeles Film Critics Association. His directorial flair also inspired Rolling Stone critic Peter Travers to rank Do the Right Thing at No. 15 on his 100 Maverick Movies of the 20th Century.

![]()

Music & Dance: Fight the Power

Still, beyond all this, Lee’s most important directorial flourish comes during the opening credits, as a debuting Rosie Perez shadowboxes and thrusts in a dance style known as “the pump.” Set to an array of urban sets and “Fresh Prince” neons, her rapid gyrations are a liberating expression of the human body that mirrors the film’s overriding theme of liberation, be it race, gender or class. The opening was so strong that Perez soon landed a dance coordinator job on TV’s In Living Color (1990), whose “Fly Girl” dancers included a young Jennifer Lopez. In a round-about way, we never would have met J-Lo without the opening of Do the Right Thing.

Of course, this opening dance would be nothing without the film’s legendary accompanying song, Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” which is featured a total of 15 times in the film. The song was recently named VH1’s Greatest Hip Hop Song of All Time and ranked #40 on the AFI’s 100 Movie Songs, one spot ahead of Sinatra’s “New York, New York.” I had a chance to see Public Enemy perform the song at the 930 Club in Washington D.C. and the group still brings it.

The lyrics are unapologetically blunt, for as Janis Joplin sang, “Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose,” or as 2Pac put it, “You can only knock on a door for so long before you start kicking it down.” (C) One verse stands out in particular: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant shit to me, you see. Straight up racist, that sucker was simple and plain, mother fuck him and John Wayne.”

Let’s take these charges one by one. The Elvis claim was later contextualized by Eminem who sang, “Though I’m not the first king of controversy, I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley, to do black music so selfishly, and use it to get myself wealthy.” Very fair point. As for John Wayne, his public conservatism is well documented, but his legacy is not black-and-white. Wayne’s critics should take a look at his single greatest performance in The Searchers (1956), one of the earliest, most subversive, most powerful strikes against racism that Hollywood has ever achieved.

![]()

Reaction & Legacy

The very debate over “Fight the Power” mirrors the film’s mixed reaction upon its release. Let’s not forget that the song’s full 7-minute music video features a newsreel of Dr. King’s 1963 peaceful March on Washington, followed by Public Enemy frontman Chuck D declaring on a megaphone: “That march in 1963, that’s a bit of nonsense, we ain’t rollin’ like that no more.”

Which brings us precisely to the debate over the film’s opposing quotes in the end credits. Detractors worried that the climax was an incitement to violence, including David Edelstein of the New York Post who wrote, “It’s good that Do the Right Thing makes us nervous, that is shows us another side to a tragedy that is tearing our cities apart. What scares me is not the chip on [Lee’s] shoulder … it’s that he thinks collective violence is warranted in response to both the killing of a young man in police custody and to a pizzeria owner’s failure to pay tribute to black culture.” Columnist Joe Klien of New York magazine expressed similar fears, calling the film “reckless” and “likely to increase racial tensions in the city,” while Stanley Crouch of The Village Voice said the film erred on the side of fascism, advocating a “reemergence of black power thinking.”

No doubt the uneasiness stems from the film’s finale, where Mookie starts a riot by throwing a trashcan through the window of Sal’s Pizzeria. The scene has since been voted Entertainment Weekly‘s #21 Movie Moment of All Time because it raises so many hard-to-answer questions (with my opinions in parenthesis). Was Sal justified in wanting Radio Raheem’s music turned down? (Yes) Did he really have to smash Radio Raheem’s boombox? (No) Did Radio Raheem overreact by attacking him? (Yes) Does this justify the loss of life? (No) Should the cops have been called to break up the fight? (Yes) But wasn’t that the same cop who diffused Frank Vincent’s racism earlier at the fire hydrant? (Yes) Did this same cop go too far in strangling Radio Raheem to death? (Absolutely) Does that justify Mookie smashing the restaurant window? (Possibly)

Lee intentionally muddies the moral waters to create a domino effect that spirals out of control. The answer to the final question — whether Mookie’s trashcan smash was justified — lies in your response to the film’s final pair of quotes. Lee presents two opposing philosophies, one by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. calling for civil disobedience and one by Malcom X calling for violence when necessary:

“Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys a community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.”

– Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.”

– Malcolm X

While this ambiguous ending may frustrate some viewers who want film endings to force-feed them messages, many critics and scholars found it masterful. The late Roger Ebert was blown away, writing, “Some of the advance articles about this movie have suggested that it is an incitement to racial violence. Those articles say more about their authors than about the movie. I believe that any goodhearted person, white or black, will come out of this movie with sympathy for all the characters. Lee does not ask us to forgive them, or even to understand everything they do, but he wants us to identify with their fears and frustrations. Do the Right Thing doesn’t ask its audiences to choose sides; it is scrupulously fair to both sides, in a story where it is our society itself that is not fair.” (B)

Decades later, when it came time for Ebert to revisit the film to write his “Great Movies” review, he reflected further: “I have been given only a few filmgoing experiences in my life to equal the first time I saw Do the Right Thing. Most movies remain up there on the screen. Only a few penetrate your soul. In May of 1989, I walked out of the screening at the Cannes Film Festival with tears in my eyes. Spike Lee had done an almost impossible thing. He’d made a movie about race in America that empathized with all the participants. He didn’t draw lines or takes sides but simply looked with sadness at one racial flashpoint that stood for many others.” (A)

And that’s the double truth, Ruth.

![]()

Citations:

CITE A: rogerebert.com, Great Movies review

CITE B: rogerebert.com, original 1989 review

CITE C: 2Pac Resurrection documentary